The point of this article is to develop an intuition: maybe 1998 was the last good year —the real last year of the 20th century, and the last “successful” year of the Washington Consensus in its Argentine, homegrown form. In other countries people might pick different favorites, but in Argentina, ’98 feels paradigmatic.

I have a few arguments to explore. First, it was the last year of GDP growth during the Menem decade; after that came a plateau and, eventually, the 2001 debacle. On some measures, Argentina’s 1998 GDP per capita would take years —more than a decade, depending on how you calculate it— to fully recover. The model was already exhausted: there was no political continuity, no third term on the horizon, and the Tequila shock had already hit. In the wake of the Cutral Có protests, with an almost-spent privatization cycle used to service accumulated debt, rising unemployment, and the murder of José Luis Cabezas, ’98 was set to go out with a bang. On May 20, Alfredo Yabrán died by suicide —at least officially— marking something like the peak of the boom, followed by a controlled descent into the early-2000s duhaldismo.

Convertibility held like a commandment carved into stone tablets, and Argentine society hoped that the Alliance —Chacho Álvarez and Fernando de la Rúa— could correct what many saw as the model’s main flaw: corruption. If the public purse stopped being looted, the thinking went, the system could finally reach stability. There were still three years to go until 2001.

With the economy on the verge of reaching its high-water mark —only to begin a rapid descent into hell— there were also other indicators of cultural maturity: books, sports spectacles, albums, and especially video games.

A quick recap: 1998 was the France World Cup. Argentina played its first World Cup without Maradona since ’78 —when he was close to being selected. We cruised through the group stage, beating Japan, Jamaica, and Croatia. We struggled against England in the round of 16: 2–2, Argentina through on penalties. Then we went out in the quarterfinals against the Netherlands, 1–2, with Dennis Bergkamp’s fateful late goal —after Ariel “El Burrito” Ortega was sent off for head-butting goalkeeper Edwin van der Sar. In Ortega’s defense: he’d been kicked all game.

That quarterfinal exit inaugurated a curse that wouldn’t be broken until Brazil 2014 —though not the separate curse of losing to Germany. If you push me, I’ll argue France ’98 was the last truly great World Cup; you only have to look at the footage to see why. Let’s score it: host country and stadiums, 10/10; mascot, 10/10; official video game, 10/10; ball design, 10/10; number of teams, 10/10; overall quality of national sides, 10/10. The final —Brazil vs. France— pit Ronaldo’s raw power (arriving below full strength) against Zidane’s masterclass, in a rivalry that would echo again in Germany 2006. And the host winning adds to the myth, in line with the old tradition of champions on home soil (Uruguay, Italy, England, Germany, Argentina).

That same year, Michael Jordan won his last NBA ring —hitting the last shot of the last game of the last Finals series against the Utah Jazz— and completed his second three-peat (1991–93 and 1996–98). It cemented a team’s place in history in a way the Bulls never truly replicated before or after Jordan. Symbolically, it also matters that this happened in Chicago —home of the Chicago School of economics, associated with Milton Friedman and the liberal orthodoxy that became hegemonic after the Berlin Wall fell. And of course: the bull as a market-up symbol.

In Argentina, 1998 also brought the last Formula 1 Argentine Grand Prix under the Marlboro name. Michael Schumacher won it. That season, the eventual world champion was Finland’s Mika Häkkinen —a friendly, almost cartoonish Nordic who, in your head, completes a trio of look-alikes with Vladimir Putin and Dave Mustaine.

On the football front, Carlos Bianchi arrived at Boca and kicked off the club’s most glorious era: he won his first title, and Martín Palermo scored 20 goals in 19 matches.

Abasto Shopping opened —turning a quintessential Buenos Aires space (the old Abasto Market) into an icon of middle-class consumption, a kind of synthesis between a fading legacy and a rising paradigm. It also marks the peak of the first wave of malls in and around Buenos Aires.

The Rolling Stones played River Plate Stadium on the Bridges to Babylon tour, with Bob Dylan as the opening act. Meanwhile, the Kosovo conflict escalated —and José Saramago, with his globally legible atheism, won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

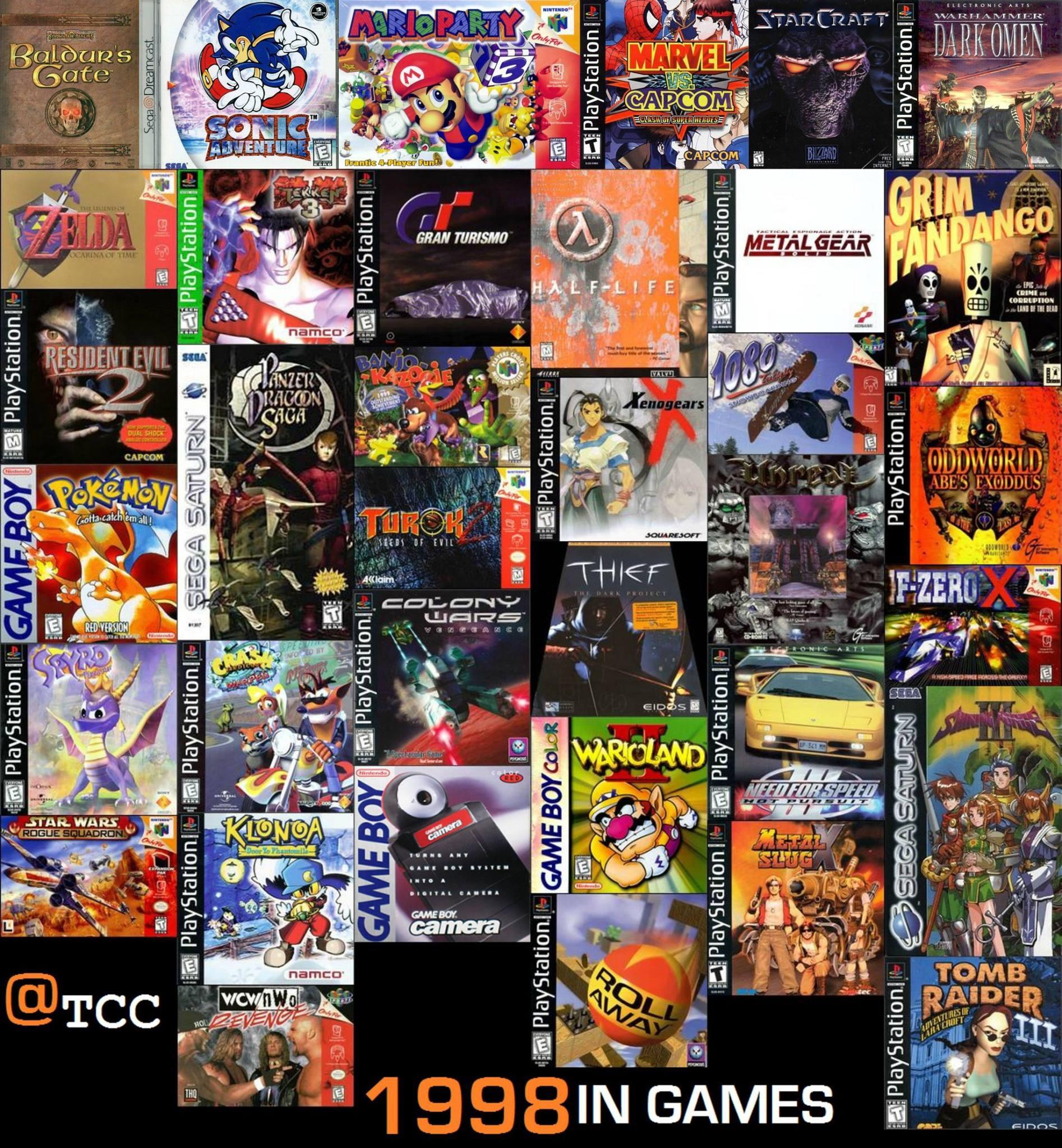

1998 in Video Games

Without a doubt, 1998 was a pivotal year for the video game industry. Quality went through the roof —classics across genres— driven by the consolidation of fifth-generation consoles and the twilight of the 16-bit era. Like many things on this list, it didn’t necessarily feel momentous at the time; it’s a retrospective ordering. Once you start checking release dates and seeing the coincidences, the amazement kicks in.

StarCraft, Age of Empires: The Rise of Rome, Commandos: Behind Enemy Lines, Fallout 2, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Half-Life, Metal Gear Solid, Grim Fandango, Resident Evil 2, Baldur’s Gate, Banjo-Kazooie, Crash Bandicoot 3: Warped, Mario Party, Pokémon arriving in the West, Caesar III, Colin McRae Rally, Dance Dance Revolution (1st edition), Gex: Enter the Gecko, Marvel vs. Capcom: Clash of Super Heroes, Need for Speed III: Hot Pursuit, Xenogears, Sonic Adventure.

The list is absurd. We’re talking about the best Zelda —and maybe the best game ever; Half-Life, which cemented Valve years before it would launch Steam; StarCraft as an RTS benchmark; Pokémon arriving in the West; Age of Empires building momentum with Rise of Rome; Mario Party; Marvel vs. Capcom; Sonic Adventure marking Sega’s jump into a new console era with the Dreamcast —a dream that didn’t last long, but we remember it with real intensity— and Grim Fandango, a landmark post-SCUMM LucasArts adventure and, possibly, the swan song of the genre.

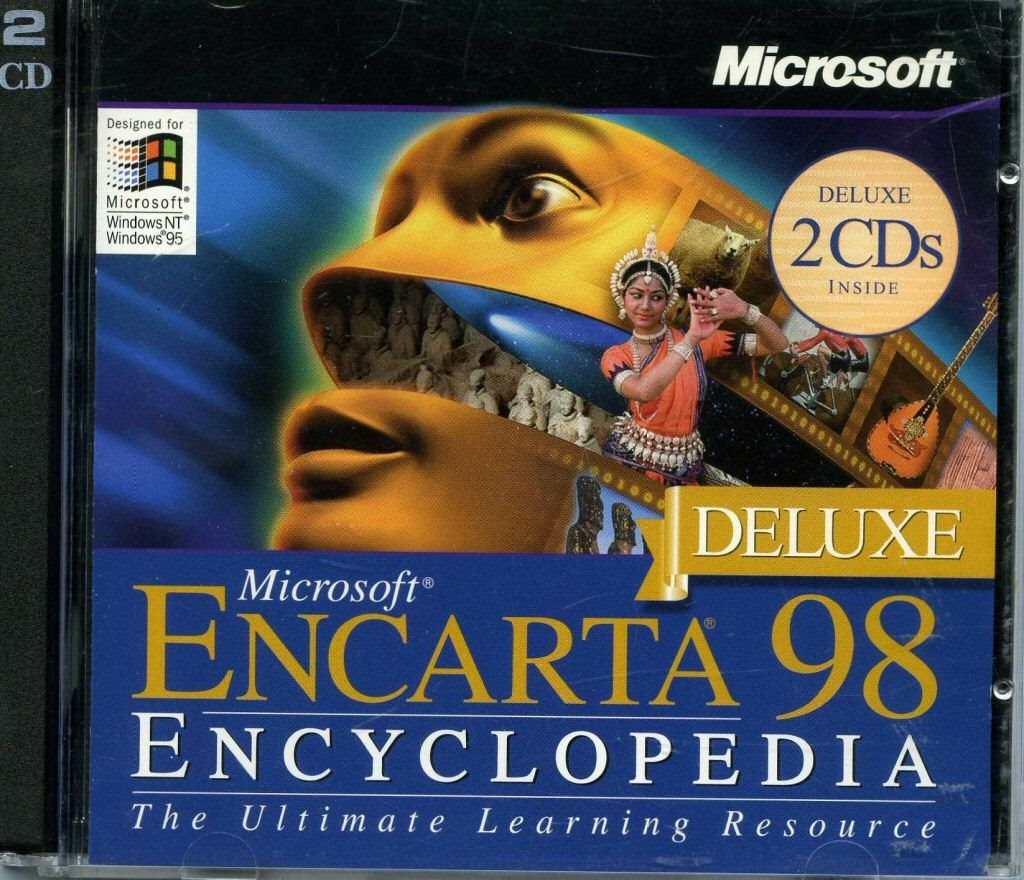

It’s hard to escape the recurring idea of a civilizational peak followed by decline, echoed across art from this period. Half-Life feels like a symbol of the end of the 20th century: a game that, in a year of insane highs, helped define the industry as we know it. In parallel, Sega reached near-terminal exhaustion right after hitting technical maturity. I think of Encarta 98 too —Microsoft building one hell of a digital encyclopedia before the internet became fully mainstream— and I can’t imagine a more Francis Fukuyama artifact than that. Every 1998 game deserves its own 421 article. Oh, and Google was founded.

Albums from 1998

But it wasn’t only an incredible year for video games —maybe the best— it was also a great year for music, in Argentina and internationally. What dominated the airwaves in ’98 is often very different from the albums I rediscover now and realize were also released in ’98.

In Argentina, we had albums that marked an era —songs that marked an era— alongside late-stage consecrations and the first signals of what was coming next: El Aguante (Charly García), Resaka (Flema), Libertinaje (Bersuit Vergarabat), A 15 cm de la realidad (Kapanga), El camino real (Todos Tus Muertos), Poder latino (ANIMAL), Arriba las manos, esto es el Estado (Las Manos de Filippi) —which contains the original “Sr. Cobranza”—, Otras canciones (A77aque), ¿Para qué? (Las Pelotas), La Renga (self-titled), Azul (Los Piojos), Gol de mujer (Divididos), San Cristóforo (Spinetta y los Socios del Desierto), Último bondi a Finisterre (Patricio Rey y sus Redonditos de Ricota), and Almafuerte (Almafuerte).

Internationally, the year was brutal. If I had to pick one defining album, it might be Madonna’s Ray of Light: the start of her second act, a sharp turn in aesthetic ambition, and —at least for me— another proof of ’98 as the “last good year”. What came next would feel harsher, even within pop. Shakira released ¿Dónde están los ladrones?, the album that put her on the map and set her path as an international star. It’s funny —almost suspicious— that Valve and Shakira share a year of canonization. A correlation worth tracking.

Aquemini (Outkast), Follow the Leader (Korn), Mezzanine (Massive Attack), Americana (The Offspring), Hellbilly Deluxe (Rob Zombie), Hello Nasty (Beastie Boys), Moon Safari (AIR), Queens of the Stone Age (Queens of the Stone Age), Believe (Cher), Yield (Pearl Jam), Garage Inc. (Metallica), You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby (Fatboy Slim), Nightfall in Middle-Earth (Blind Guardian), Walking into Clarksdale (Page & Plant), System of a Down (self-titled debut), and two personal favorites: Frank Black and the Catholics (Frank Black and the Catholics) and The Sound of Perseverance (Death).

I’m not sure there’s anything more “end of the 20th century” than the last Page & Plant studio album —recorded at Steve Albini’s— and the last Death studio album, by pioneers of death metal. Chuck Schuldiner would die, ironically, in December 2001.

Films from 1998

As if all this weren’t enough, we still have to list the year’s most significant films. In Argentina, the selection captures the duality of exhaustion and peak-Menem excess: Un argentino suelto en Nueva York (Francella, Oreiro); Dibu 2: la venganza de Nasty; El Faro, Eduardo Mignogna’s award-winning drama featuring a who’s-who of the era (Darín, Norma Aleandro, Marrale, Boy Olmi, Jimena Barón), pointing toward the kind of Argentine drama that would soon become canonical; and, finally, Pizza, birra, faso (Stagnaro & Caetano), a banner film of New Argentine Cinema —a staging of the model’s underside and the starting gun for two of the most important directors of the 21st century. Add them to Valve, Shakira, and SOAD.

Internationally, it was a wild year. At the box office, Armageddon led the pack —Aerosmith anthems included— and beat out Deep Impact, a near-twin released the same year (classic Hollywood duplication). Then comes the year’s most influential film: Saving Private Ryan, a canonical reset for WWII cinema that reshaped the genre’s visual language —and, downstream, the look of early WWII shooters.

Also in the mix: Godzilla (Roland Emmerich), a notorious flop that still left a major soundtrack moment; There’s Something About Mary, which helped define a wave of late-’90s comedy; BASEketball (Matt Stone & Trey Parker), a ridiculously good cult comedy; and Half Baked, a stoner cult classic with Dave Chappelle and Jim Breuer.

And we’re not done: A Bug’s Life (Pixar) and its slightly less beloved twin, Antz —another case of dueling lookalikes, where the “good one” did better. Mulan. Shakespeare in Love, which won Best Picture. Then things get serious: Lethal Weapon 4; A Perfect Murder; Snake Eyes; The Thin Red Line (Terrence Malick), another WWII masterpiece released under the shadow of the year’s other giant; Vampires (John Carpenter), whose first half hour is pure party; Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Terry Gilliam); American History X; Ronin (De Niro, Jean Reno, Sean Bean; script by David Mamet); and The Truman Show, with a legendary Jim Carrey performance.

It keeps going with what I call the “conspiracy trilogy”: The X-Files hits theaters and ends with the unforgettable shot of a craft in Antarctica; The Siege (Bruce Willis, Denzel Washington) imagines terrorist attacks in New York culminating in a general imposing martial law; and Enemy of the State (Will Smith, Gene Hackman, Tony Scott), the first time I heard the phrase “Faraday cage”.

And to close: Small Soldiers, A Night at the Roxbury, Run Lola Run, The Mask of Zorro, Meet Joe Black, City of Angels, and —last but absolutely not least— Blade, with Wesley Snipes.

Oh, and Pokémon: The First Movie (released in Japan in 1998), which is basically Akira + Pikachu. And Wag the Dog, written by David Mamet and starring De Niro and Dustin Hoffman, about a fictional Balkan war engineered to cover up a presidential scandal involving a White House intern. The film hit the same year the Lewinsky scandal broke, during Bill Clinton’s final years in office —years that also overlapped with the Balkans burning.

After collecting all this anecdotal evidence, I think it’s enough to argue that ’98 was the last great year of the previous century —before the crises that would catapult us into the 21st, internationally (September 11, 2001) and locally (December 19–20, 2001).

And yes: 1998 also gave us iconic Magic: The Gathering expansions —Stronghold, Exodus, and Urza’s Saga— so powerful they nearly broke the game, in what’s remembered as “Combo Winter”. Jon Finkel was at the center of that era. But that’s another article.