1981, a pivotal year in the Golden Age of arcade machines. The arcades are bursting with teenagers who spend their limited cash on tokens that allow them to spend hours playing (or watching others play) video games like Space Invaders, Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, Asteroids, or Tempest. They are community spaces for recreation, places to make friends but also to gain enemies in pixelated battles. One afternoon, in a few arcades in Portland, Oregon, a mysterious arcade appears, set apart from the more popular titles, with no more information than its name emblazoned in fluorescent green above the screen: Polybius.

At first, the game doesn't seem to catch the attention of the crowd, but as days go by, some begin to feel drawn to that marginalized machine and decide to give it a try. It's a space shooter game with vector graphics, hypnotic effects, and an unusual mechanic, because instead of moving the ship, the player rotates the screen around it. Suddenly, Polybius becomes popular in those two or three arcades in Portland; it seems destined to become a cult video game, until the problems start.

The first thing regular customers of those arcades notice is that there are several players who, more than fans, are addicted to Polybius. The compulsion it generates in certain youths, witnesses say, drives them to steal or prostitute themselves for a few coins, just to keep playing. Those who dare to play it claim that as they progress in the game, things get increasingly strange: ghostly faces and subliminal messages urging submission and even suicide flash on the screen for milliseconds. Some kids no longer want to even approach the arcade after witnessing the adverse neurological effects it has on players: dizziness, nausea, fainting, and in the worst cases, convulsions, stress, and night terrors. Even those who weren't paying much attention become concerned when rumors spread that, after the arcades close, men in black appear to talk to the owner, take notes, and tamper with the arcade's hardware. Until tragedy finally strikes: on the same day, a 12-year-old boy dies from an epileptic seizure while playing Polybius, and another preteen dies of a heart attack on his way home after hours hypnotized in front of the machine. Shortly after these deaths, Polybius disappears not only from Portland but from the face of the Earth: several witnesses claim to have seen men in black removing the arcades from the establishments. The cursed video game vanishes forever, leaving no trace but the oral accounts of those who played it and survived.

June 25, 2015. The YouTube channel Obscure Horror Corner uploads the first in a series of videos containing fragments of a dark, unsettling video game that is said to be potentially dangerous. Jamie, the creator of the channel, confesses to the gaming website Kotaku that days earlier he had delved into the deep web following a lead from a subscriber of his channel. On an Onion site (a hidden webpage accessible only through the Tor browser), he found a file named Sad Satan that contained a game. After verifying that the file was free of malware, he downloaded it and began to play. Jamie recorded those gameplay sessions and decided to add them to the channel, perhaps unaware that these would be the last videos he would upload before disappearing from the internet forever. Thus, the channel Obscure Horror Corner became a kind of digital haunted house, an abandoned and cursed online space that every horror and weirdness fan visits to have a good/bad time watching gameplay of a video game that emerged from the deep web. Sixteen years later, the first video in the series has garnered 4.2 million views.

The gameplay uploaded to Obscure Horror Corner shows a first-person game with low-resolution graphics and monochromatic colors, a walk simulator where the player navigates a vast liminal space made up of dark hallways and empty rooms, assaulted by unsettling sounds (distorted audio, phrases from serial killers, reversed songs, cries, whispers, and deafening screams), and disturbing images that suddenly invade the entire screen, preventing the player from progressing and forcing them to stare at them for a few seconds. These images range from uncomfortable works by artists like Walter Sanders or Roger Ballen to photos of notorious pedophiles, child murderers, and necrophiles.

But the real Sad Satan appears on July 7, 2015, when, minutes after new statements from Jamie are published in Kotaku (where he claimed to have removed scenes with extreme and illegal graphic content from the gameplay), an anonymous user on the 4Chan forum posts a download link that, he claims, contains everything that the "coward from Obscure Horror Corner" was too afraid to show. Those who dare to download it find a more extreme Sad Satan, which includes real photos of mutilated corpses, images of pedophilia, and malware. A much more complete representation of what is expected from the deep web.

Polybius and Sad Satan are two clear examples of cursed video games that have taken a strong hold in popular imagination: one became an example of manipulation and mind control (in the style of MK ULTRA) through entertainment; the other is synonymous with the deep web and its horrors.

But the only truth behind these popular tales is that, at least initially, none of these games existed. They were urban legends (or perhaps, given that they are narratives from the internet age, it would be more appropriate to call them digital myths or creepypastas), until they escaped their fictional universe and entered our reality.

The existence of Polybius has never been proven, and all its lore was likely inspired by real cases of children who suffered fainting spells or seizures while playing arcades of the time like Asteroids, Astro Fighters, or Tempest in the city of Portland. The earliest mentions of Polybius date back to the year 2000, and no references to the arcade could be traced back to the eighties or nineties. There is also no audiovisual evidence, and those who claim to have a ROM of the game have never shown proof.

Polybius, then, was an internet legend created in the early years of the new millennium… Until the developer Llamasoft made it a reality and released it in May 2017 for PlayStation 4 and PlayStation VR, while rumors circulated that its founder had accessed one of the original arcades supposedly hidden in a warehouse located in Hampshire, England. This new version of Polybius is a trance shooter, a shooting game designed to place the player in a trance state through its repetitive and chaotic gameplay and psychedelic graphics. Its creators sought to experiment with the psychological and hallucinogenic possibilities offered by virtual reality and induce the player to "get in the zone" (that state of concentration and absolute immersion known as "flow") and thus recreate, in a way, that sensation that resonated so strongly in the collective imagination, but without the harmful neurological consequences.

In the case of Sad Satan, no one (except Jamie, the creator of Obscure Horror Corner) was able to play the original version, nor has it been proven that it came from the deep web. The second version of the game, which an anonymous user posted on 4Chan, turned out to be a clone, a truly dangerous and grotesque copy filled with malware and images of child abuse, with the same mechanics and narrative as the original version, but with certain differences that revealed it was not the same game. In other words: that cursed, illegal, and twisted video game that was supposed to be pulled from the depths of the deep web (but which existed only in a gameplay), materialized and became available for free download, but only once the hype was strong enough for someone to develop it and make it real.

The philosopher Nick Land (founder along with Sadie Plant of the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit-CCRU at the University of Warwick, England) defined hyperstitions as "positive feedback circuits that include culture as a component (...) experimental technoscience of self-fulfilling prophecies. Superstitions are nothing more than false beliefs, but hyperstitions – by their existence as ideas – causally function to create their own reality." Hyperstitions, then, not only enter our reality but also modify and update it. While superstition involves practices that seek to repress something undesirable (for example, knocking on wood or avoiding walking under a ladder), hyperstition opens channels and generates "hyperstitional rips" through which fictional artifacts slip in, and upon entering our reality, cease to be fictional.

Both Polybius and Sad Satan are hyperstitions, semiotic productions that became reality, initially fictional artifacts that, thanks to the hype, entered reality and updated it.

September 2016, Spain. The publisher Candaya releases the first edition of Nefando, a daring and controversial novel by Ecuadorian writer Mónica Ojeda. Through a fragmentary, polyphonic structure, and using a variety of formats (interviews, chats on a deep web forum, chronicles about a video game, fragments of a pornographic novel, illustrations, etc.), Ojeda narrates the story of six young people sharing an apartment in Barcelona. Three of them (the Terán brothers) commission the creation of a video game from Cuco Martinez, their roommate, hacker, and game designer. The game in question is called Nefando, and it is said to have been available online on the deep web until it was removed due to its abhorrent and illegal content, which included videos of mutilations, necrozoophilia, and child abuse. Like Sad Satan, Nefando was hosted on an Onion site and had no clear rules, instructions, or levels to overcome. It was a game for voyeurs: "Nefando trapped its players not because it entertained them, but because it had the power to awaken a curiosity... how can I put it?, morbid, that grew larger inside you, you know, like a stain throbbing above your navel."

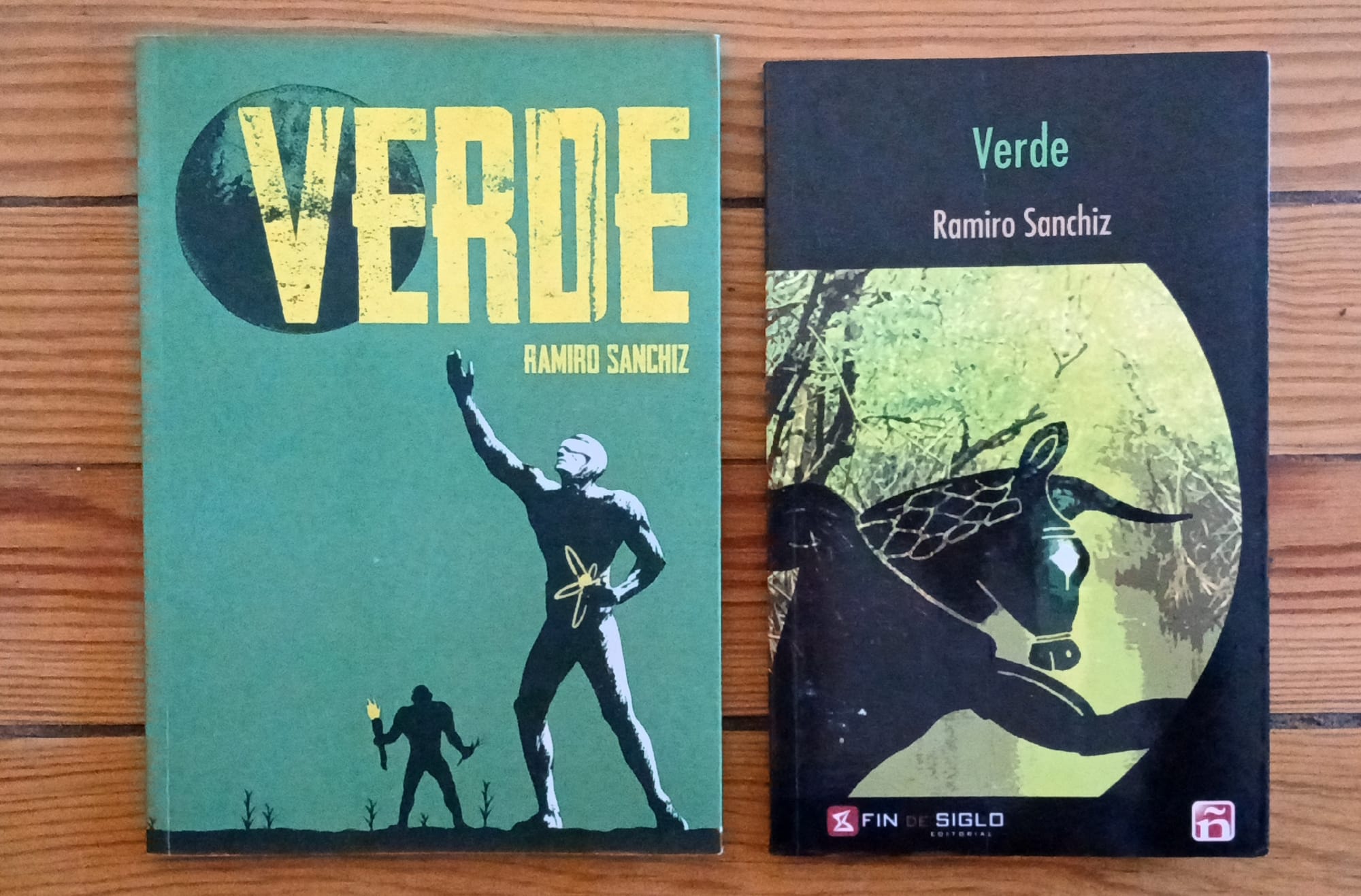

September 2016, Uruguay. In parallel to the publication of Nefando, the publisher Fin de Siglo releases Verde, a weird novel by prolific writer Ramiro Sanchiz. In Verde, Sanchiz narrates the encounter of two children with a dead creature in a lagoon on the Uruguayan coast, and the aftermath this contact leaves on the psyche of both kids. This entity, likely alien, with an impossible and changing appearance, seems to sicken those who come into contact with it, provoking a complex mutation that induces visions, delirium, and ultimately destroys the mind. The protagonist and narrator of the novel hears rumors about shelters where those who have suffered most severely from contact with the alien entities are confined. Through a friend, he learns that photographs of those shelters circulate on the deep web, linked to a video game called Tonneru, a kind of walk simulator that consists of traversing a claustrophobic and repetitive liminal space with a circular tunnel, with no apparent objective other than unlocking photographs of mutilations, totems assembled from parts of human bodies, animals with human limbs grafted on, and among them, images of the shelters. Tonneru (whose influences are both Polybius and Sad Satan) is described as a game that overwhelms and generates a terrifying psychological weariness, multiplying the player's anxiety and turning them into a paranoid or a psychopath in a constant state of alertness:

"A couple of Japanese gamers – true hikikomori recluses in their rooms, scholars of manga, anime, and j-horror cinema – said they abandoned it not long ago, more or less for the same reasons as Valeria (they had begun to suffer nightmares in which the hallway of the video game progressively became shorter), and with a considerable sense of pride, they recounted that they had managed to unlock six of the photographs" (Verde).

It is clear that the Sad Satan event and everything surrounding it (the hype, the morbid curiosity, the rumors, the myths, the clones) was such a suggestive cultural phenomenon (especially within horror enthusiast circles) that, despite starting as an underground phenomenon, it expanded to become an internet legend and reached two Latin American writers who decided to reimagine it (one from the most visceral realism and the other from strange fiction) and make it part of their novels.

At the same time that Nefando and Verde were published, American writer B. R. Yeager was writing Amigdalatropolis, which would be published in the early days of 2017. While in their respective books Ojeda and Sanchiz touch on the topic of the deep web tangentially to focus almost exclusively on the chilling content of the video game and the sensations of the players, Yeager dives headfirst into the muck of the dark web (the deepest and truly messed-up part of the deep web), the dark forums, and the most extreme currents of online culture. The protagonist is a hikikomori recluse in his room, an alienated young man whose only connection to the world consists of interactions with other anonymous users on a 4chan-style forum, a virtual space where they gather to distill a profound misanthropy, organize doxeos or swateos (false reports intended to have a SWAT team burst into the home of someone who is playing online or streaming live), reinforce their racist, xenophobic, and misogynistic ideas, and share photos and videos of murders, suicides, mutilations, rapes, or infanticides, among other perversions. In Amigdalatropolis, two disturbing and violent online games also appear, but in a conversation I had with Yeager, the writer assured me that he learned about the existence of Sad Satan only when he was about to finish writing the novel, so it had little influence on his writing. However, similar games did influence him: vulgar ROM hacks and strange Flash games, odd PC games by hobbyists with a shocking twist. Yeager also told me that he wrote Amigdalatropolis at the height of his interest in video game design, during a time when he considers the medium was much more open and strange than today: "Obviously, video games have always been a massive commercial format, but nowadays the medium seems hyper-commercialized and much less interesting unless you delve into the underground scene."

At this point, I suppose there's an impossible question to avoid: What happened during 2016 that led three young writers from different parts of the world to decide to write about the same themes, even when these themes (the horrors of the deep web, the perversion of certain online forums, cursed video games) were far from popular at that time?

Beyond significant cultural events like the death of David Bowie and the release of the groundbreaking video game Pokemon Go, there are certain events related to the internet, social media, and politics that need to be contextualized to understand how and why novels like Nefando, Verde, and Amigdalatropolis were published in 2016, when concepts like deep web, doxeo, or troll were unknown to the vast majority of human beings:

- The theorists of the dead internet believe that 2016 is the year when the internet as we knew it began to die, and what we see today is, for the most part, AI-generated content meant to be consumed by bots, creating a vicious cycle of artificial interaction that excludes human beings. So, if the vast majority of internet traffic comes from bots, it is logical to assert that there are few humans left interacting with each other online. This, which just a few years ago seemed like another crazy conspiracy theory, a simple apocalyptic-digital fantasy, seems to become more real every day, as if it were a hyperstition.

- For B. R. Yeager, 2016 marks the beginning of the end of the golden age of Web 2.0. Although the internet was never a utopia, until that year it still felt like a place to play with identity and creative expression; since then, it has become a more corporate space, less strange and personal, a shift that had been happening throughout the previous decade but began to accelerate from 2016 onward. Ramiro Sanchiz, like Yeager, believes that the disillusionment with the internet among those who promoted the idea of a digital utopia (like Wire, for example) had already been occurring, but 2016 is the key year that recontextualizes all that cyberdelic optimism of the nineties.

- 2016 was also the year when 4chan emerged from the digital underground and had its moment of mainstream glory when some of its anonymous members (particularly users from /pol/, the channel dedicated to political incorrectness where white supremacists, neo-Nazis, xenophobes, homophobes, etc., gather) supported Donald Trump through various coordinated actions during the presidential campaign, to which Trump responded by appropriating their most iconic meme (the Pepe frog) and using it as part of his campaign. In this back-and-forth, direct links were created between him and these online communities, which, in their own way, helped propel Trump to the presidency of the United States through misinformation campaigns, trolling, mass harassment, and what they call "meme magic," which is not too far from the concept of hyperstition (and which had its own expressions in Argentina).

Yeager understands that 2016 is the year when these internet subcultures officially broke containment and seized public consciousness. One of the clearest examples is when Hillary Clinton mentioned the Pepe frog in one of her campaign speeches: "I wrote Amigdalatrópolis specifically because it dealt with unknown subcultures that I assumed would never break through, so it was surreal to see them recognized by more conventional figures and media. Ten years ago, I would have called you crazy if you had told me that my parents would someday know who Curtis Yarvin is, but they do," Yeager reflects. Nowadays, the antisocial and reactionary extremism that was hidden in virtual underworlds like 4chan and 8kun has gone mainstream. Today, in Argentina, it’s common for the media and social networks to talk about "troll armies," and some of those trolls have even been turned into public officials. The average internet user has a more or less clear idea of what a forum is, what a meme is, what it means to dox, or who the hell Pepe the frog is, thanks to the popularization of these topics through essays like Is Democracy in Danger? (2023) by Juan Ruocco. But in 2016, all that internet underbelly was still uncharted territory for most, which is why the creators of Sad Satan could play with the idea of an unknown and almost mythological deep web that was becoming populated with dark legends and monsters (some very real) that popular imagination could accept, but also create.

Perhaps both Mónica Ojeda and Ramiro Sanchiz sensed the imminent rupture between these clandestine digital subcultures and the mainstream, which is why they decided to write about these topics. Perhaps they understood that the new monsters should no longer be sought in ancient urban legends or classic oral tales, but in the fictions that become real in themselves, in digital myths and creepypastas that replicate and spread like a virus across the network. Or perhaps, like B. R. Yeager, they believed that these subcultures would not endure over time, that they would disintegrate and self-destruct, and that’s why they sought to document them before that happened. But unfortunately, the opposite occurred, and today the packs of disturbed individuals filled with hatred behind the anonymity of the networks are pop, they are mainstream, and they are cool.