The Wizard prepares his spell, a die rolls and shows an 8, a 13, a 5, for a moment you see a 20, but it lands on a 1. All those numbers were possible futures that didn't happen. The group of players falls silent because the 1 marks a fatal result, a critical failure that transfers from probability to narrative.

This classic tabletop RPG sequence happens on three different planes. On the fantasy plane, a wizard casts a spell; on the plane of the system that gives rules to that world, a die gives a result of 1; and on the plane of experience, a group of players want to die because of what that roll is going to unleash. The tabletop RPG is a fascinating experience in which we fuel our imagination alongside -- generally -- a group of friends. And we couldn't be talking about this without the first, the undisputed but also much-disputed king: Dungeons & Dragons.

While at 421 we've already covered tabletop RPGs like MORK BORG and Cairn, we owed ourselves a look at the one that started it all. Dungeons & Dragons is a global phenomenon that from a super specific and small niche managed to infiltrate the most mainstream corners of culture. So you don't get lost in the dungeon, we're going to review the fundamentals and foundations of this game that changed the rules of playing with imagination.

What Is a Tabletop RPG? The First Question in the Manuals

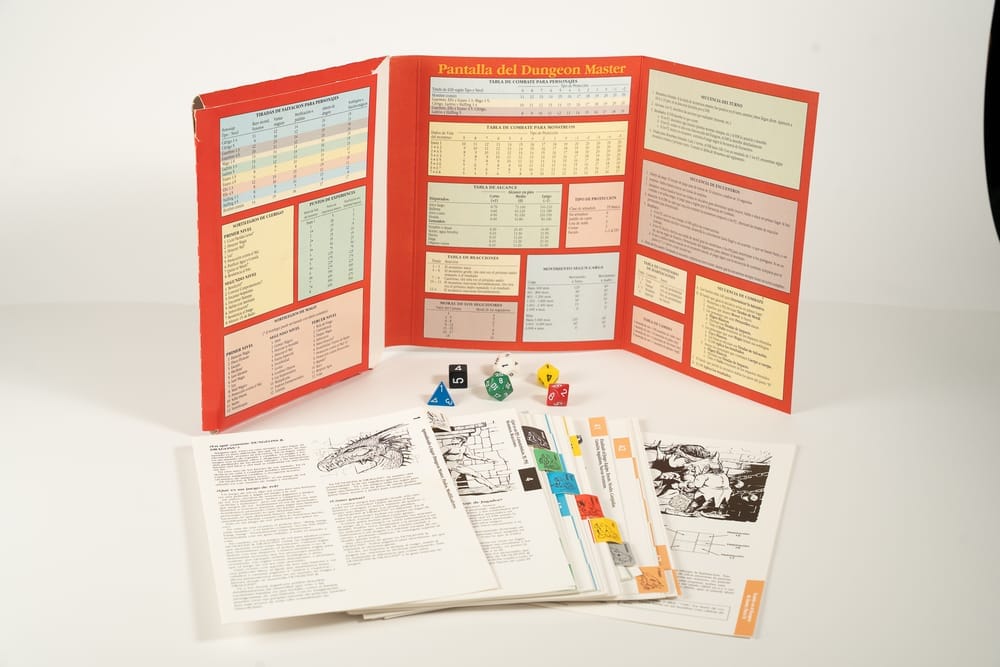

Tabletop RPGs are collaborative experiences where, through a system of rules, players roleplay characters and create stories with their decisions. Generally, one of these players is considered a "referee," called the Dungeon Master or DM, who controls the main narration and the use of the system.

As in the example at the beginning of the article, this universe works in three layers. The layer of the lore or setting of the game, which can be science fiction, fantasy, detective, etcetera, and which sets the foundation of the story to be played. Then the layer of the system, which can be more narrative or more action-oriented, and which provides the context of probabilities for the results of the actions the players want to take, for which dice or randomness systems are usually used. And finally there's the layer of the players themselves, who make decisions based on the system and setting, and can interact with each other as the characters they play or step back and talk as players, creating a metagame space.

The objective of a D&D session is usually tied to the setting. For example, killing a dragon that's tormenting a village. But there's no objective to "win" like in classic board games like chess, since tabletop RPGs focus on the experience of collaborative narrative creation. We could say that playing an RPG is interpreting a fantasy with a system of rules. And the first to do it was Dungeons & Dragons.

War and the Birth of Roleplaying

War, war never changes. But as an engine of epic and tragic stories, it certainly changes people, environments, cultures, and even games. There's a bloodline connecting modern games like Warhammer with Napoleon Bonaparte, who ran battle simulations with wooden soldiers on a table that recreated the battlefield.

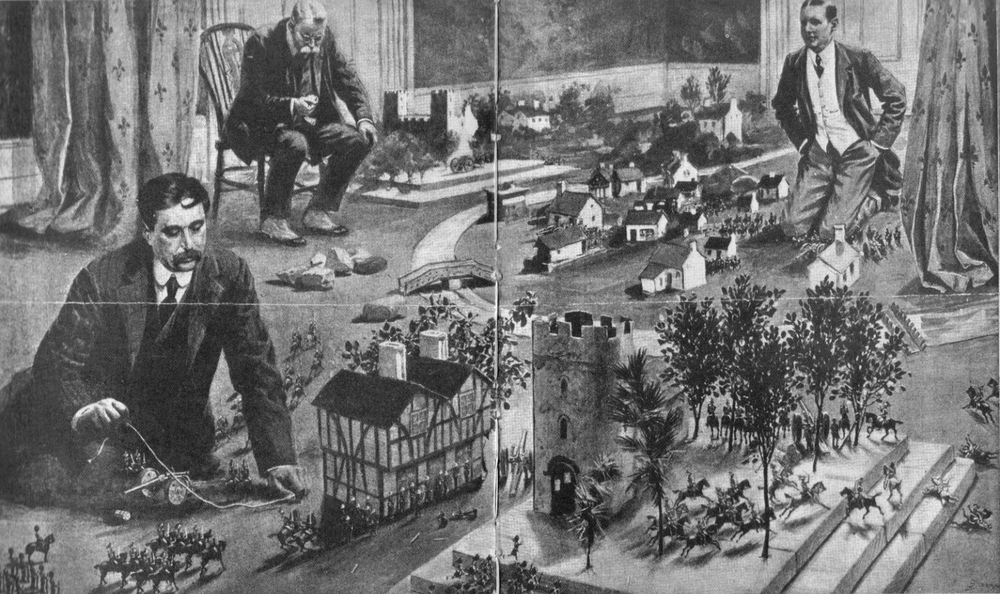

But if we look closely, it was in 1913 that writer H.G. Wells (of The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine) created the first published wargame manual, under the name Little Wars. Wells's proposal was to play with lead soldiers, which at the time were collectible items or children's toys. Over the years, Little Wars became a full-fledged hobby and by the 1950s and '60s, wargames were being played in gaming clubs across Europe and the United States. Like any nerd club, the DIY virus became vital to keeping this small scene alive, and players began modifying Little Wars to add more options or straight-up create new games.

Gary Gygax was a nerdy fellow who was part of the International Federation of Wargaming. In 1971, together with Jeff Perren, they published Chainmail, a rulebook for medieval combat with miniatures based on Little Wars but with more options and flexibility. Soon after, this duo would release the Fantasy Supplement that adapted Chainmail from a medieval war game to being able to play battles in the style of The Lord of the Rings (which at the time was the nerdiest and most amazing work that could exist).

The important thing about Chainmail is the chain reaction it started, because this manual would blow the mind of another nerdy fellow named Dave Arneson, the other, lesser-known father of Dungeons & Dragons. Arneson took Chainmail's rules and its fantasy supplement and with that created an "expansion" he would call Blackmoor. This mad genius had added unique characters, dungeons, and an event system to play a campaign that blew Gygax away. Together they began working on something new that was initially called Chainmail: Dungeons & Dragons. In 1974 the First Edition was released, the so-called White Box, with this statement:

These rules are strictly fantasy. Those wargamers who lack imagination, those who don't thrill to the adventures of Burroughs' John Carter crawling through dark pits, who feel no excitement reading Howard's Conan sagas, or don't enjoy the fantasies of Camp & Pratt, nor Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser of Fritz Leiber battling sinister sorcery, will not enjoy DUNGEONS & DRAGONS. But those whose imagination knows no limits will find that these rules are the answer to their prayers. With this final piece of advice, we invite you to read and enjoy a "world" where the fantastic is real, and magic truly works!

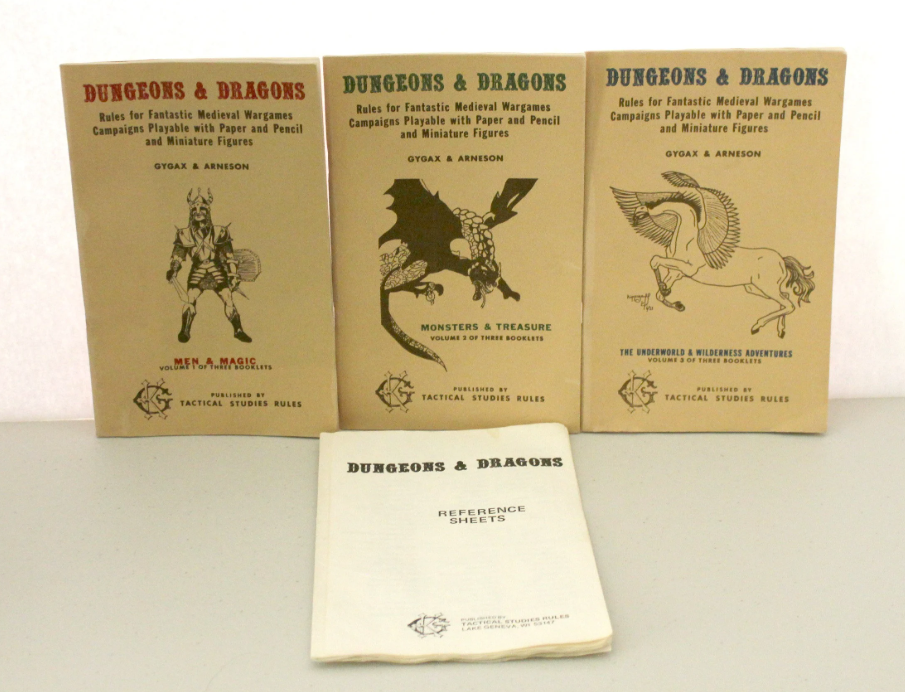

That first box contained three manuals of about 50 pages each, with all the information needed to play or be a DM. The first manual, Men & Magic, already laid down the steps for creating a character (which would be used in almost every game that followed) with the first classes you could use (fighters, magic users, and clerics). Races were also present from the earliest rules, encouraging play as humans but also presenting dwarves, elves, and halflings (hobbits), along with spells and abilities. Another important feature that came out in that edition, which today is used as a meme, is alignment, for which in its first version there were only lawful, neutral, and chaotic.

The other manuals included were Monsters & Treasure, with a list of monsters, treasure tables, equipment, and magic items; and The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures, where you'll find the DM rules for designing dungeons and adventures.

Leveling Up

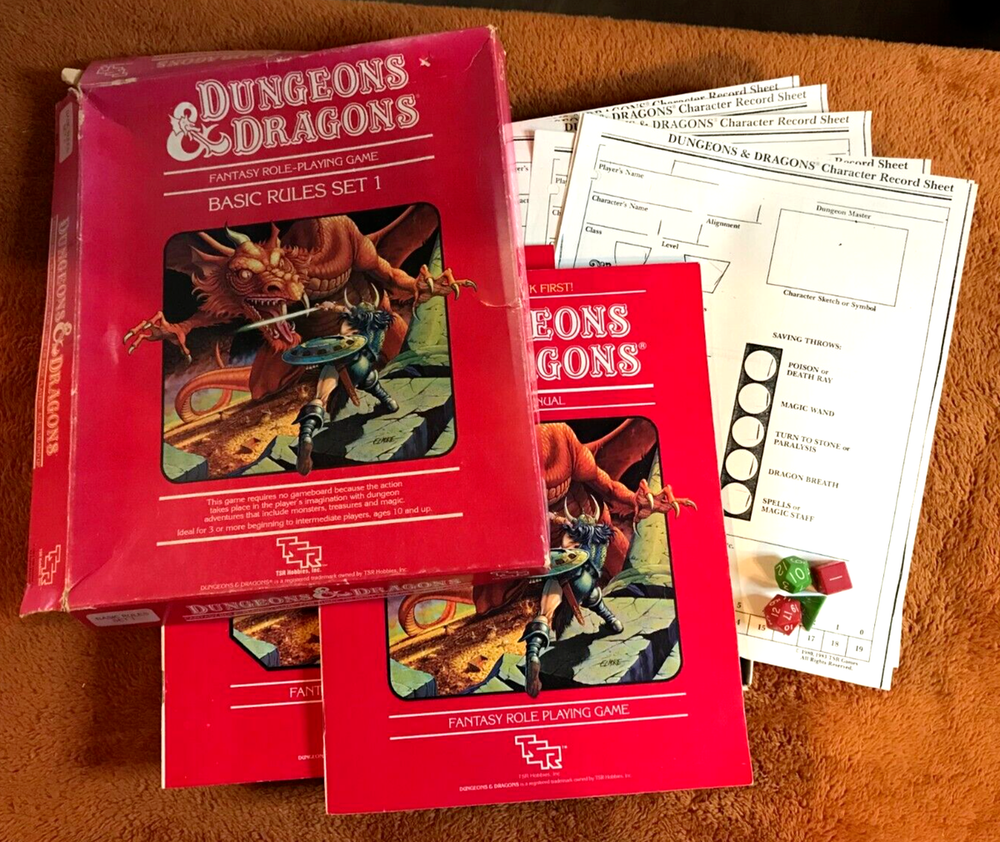

During the following years, the game expanded with supplements like the return of Blackmoor and, toward the end of the '70s, consolidated into Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, now with more complete rules and manuals that defined the entire decade of the '80s. It was also the period of greatest popularity, with the 1983 release of the famous Red Box for new players, but also with controversy from conservative sectors who associated it with satanism.

The '90s brought the Second Edition, with new rules and the beginning of many supplements that added new gameplay and campaigns. This edition fueled legendary video games like Baldur's Gate (1998) and Planescape: Torment (1999). The Third Edition, in 2000, introduced the famous d20 system, which served as the base for dozens of other games. In fact, the fork Pathfinder was born from this, gaining enormous popularity and a large player base. The Fourth Edition (2008) went for a tactical, video game-like design and was a misfire that hit the brand hard. Finally, the Fifth Edition (2014) revitalized the franchise with more accessible and narrative rules, along with a strong push into digital content. Thanks to content creators like Critical Role on streaming and the game's appearance in the series Stranger Things, Dungeons & Dragons re-entered the mainstream to win over new players. Today the brand is moving toward One D&D, a digitized evolution compatible with the Fifth Edition.

Argentina Is a Dungeon

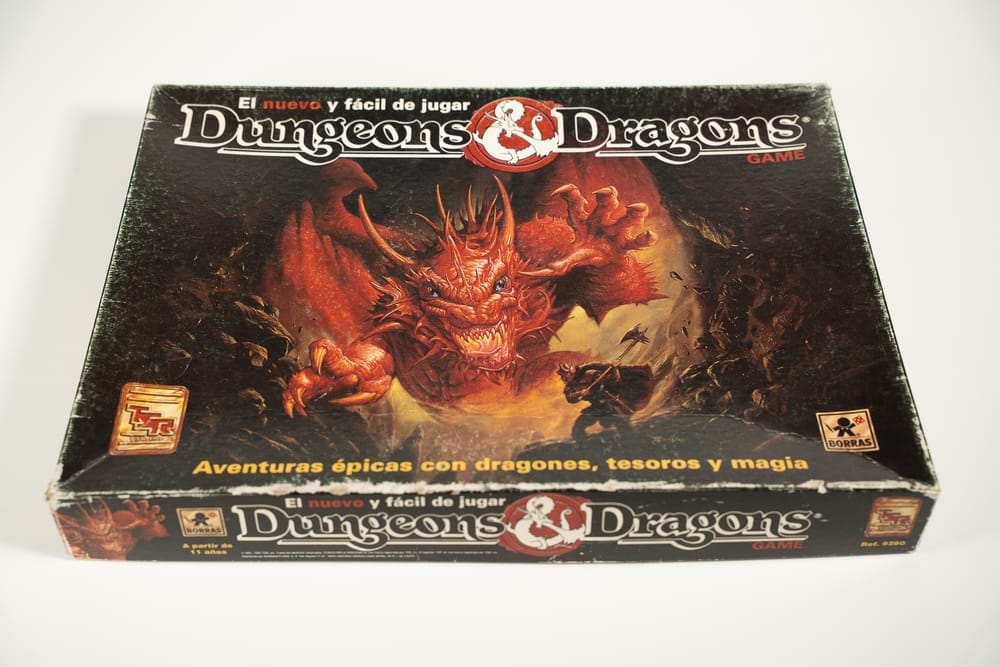

The first edition of Dungeons & Dragons, which was called Calabozos y Dragones in Spanish, was published by Zinco (a Spanish publisher of comics and nerdy books that held DC Comics titles) in 1985 and was a translation of the basic set known as the Red Box. In parallel, a starter box called the "Black Box" was released by the publisher Borras. Zinco was in charge of D&D publications until the mid-'90s when the brand switched to a publisher specializing in RPGs, La Factoria de Ideas, who had become very popular for being responsible for the translations of Vampire: The Masquerade and the other World of Darkness games by White Wolf.

By the early 2000s, Dungeons & Dragons found a home with Devir, which not only handled the translation but also distributed the game to other Spanish-speaking countries. Currently, the people translating and distributing the game are Edge Entertainment, who hold several of the most popular IPs in tabletop RPGs and board games.

In those early years of Zinco, the material arrived in Argentina the same way Warhammer did: someone brought it from abroad and it was distributed among players thanks to the power of the photocopier. Suddenly, RPGs started circulating in universities and among people who played board games/wargames, or in fan clubs like the Tolkien Association of Argentina. Clearly, all super niche spaces. But unlike other hobbies, all you needed for RPGs was a pencil, paper, a few dice, and for five people to share a copy of the rules. This made it super accessible and it went viral among those early Argentine nerds.

Little by little, Spanish-language material started appearing at Parque Rivadavia, at the first comic book shops, at quirky bookstores or hobby shops like Top Gun in the Buenos Aires city center. By the early '90s a new factor emerged: the appearance of gaming clubs that organized events to play RPGs, wargames, board games, and Magic: The Gathering, which were also spaces for buying, selling, and trading material, from original manuals to photocopies.

It is said that the country's first RPG convention was organized by the club El Dragon de Humahuaca in 1991 and that the first convention at Ciudad Universitaria came in 1993, organized by the club Juegos de Que?. By 1994 several clubs were up and running, including La Cofradia del Sur, Fraternitas Veri Ludi, and Dragon Verde. This tradition of clubs lives on in new virtual and physical spaces, and in commercial game shops or comic book stores that started adding RPGs to their activities.

With nearly 50 years of history, Dungeons & Dragons remains a touchstone, though it now coexists with a ton of other games that, like Blackmoor in its day, take from it to create new things. In the last decade, boosted by the post-pandemic era, the RPG circuit was strongly revitalized, also welcoming independent publications, giving us new games like MORK BORG, Cairn, Shadowdark, or Dungeon Crawl Classics. Some modern games are even more recommended today than D&D itself, but Dungeons & Dragons is foundational, it's Black Sabbath to metal. Allow yourselves to play this classic, especially in its Advanced or Second Edition, to understand its legacy.