At a slow, heavy, exhausted pace, a masked psychopath chases teenagers through a forest, a campus, a school –it hardly matters where. In his hand he carries a machete, a hammer, a chainsaw, a bladed glove –almost anything. With just those elements you can hear the tension and the music and picture the pop-horror scene –on the big screen, or more often on a TV with a VHS deck or late-night cable, with friends and pizzas.

Slasher cinema is a genre with a lot to unpack –especially its golden era in the '80s and '90s, when horror went full MTV and pop. For many teens it was a ritual: who could stomach it, who would sneak a peek at on-screen nudity. The key lies with its leads –not the hunted teenagers but the monsters. A new pantheon of horror gods took root in pop culture as the slasher coalesced in the late '70s around masked psychopaths.

Put on your favorite mask and grab the machete –today you become a monster.

Masked Psychopaths Hunt Teenagers

In the '60s and much of the '70s, horror fed on a Gothic imaginary –think Hammer Films and Vincent Price. But with Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960), fear left the spectral castle for more mundane, urban spaces. The original scream queen, Janet Leigh, was born there, and the psychopath emerged as the new monster.

Around the same time in Italy, giallo rose under Mario Bava and Dario Argento: masked killers with sharp weapons, Gothic-to-Baroque tones, and stylized violence. Those elements moved beyond Poe-style fears and set the stage for the two films that would crystallize the slasher.

With The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974), the pieces snap into place: a group of youths hunted by a masked psychopath wielding a devastating tool in a recognizably rural setting; in the end, everyone dies except a lone girl who lives to tell it. Leatherface became the saga's face –and the first new-era psychopath in the pantheon.

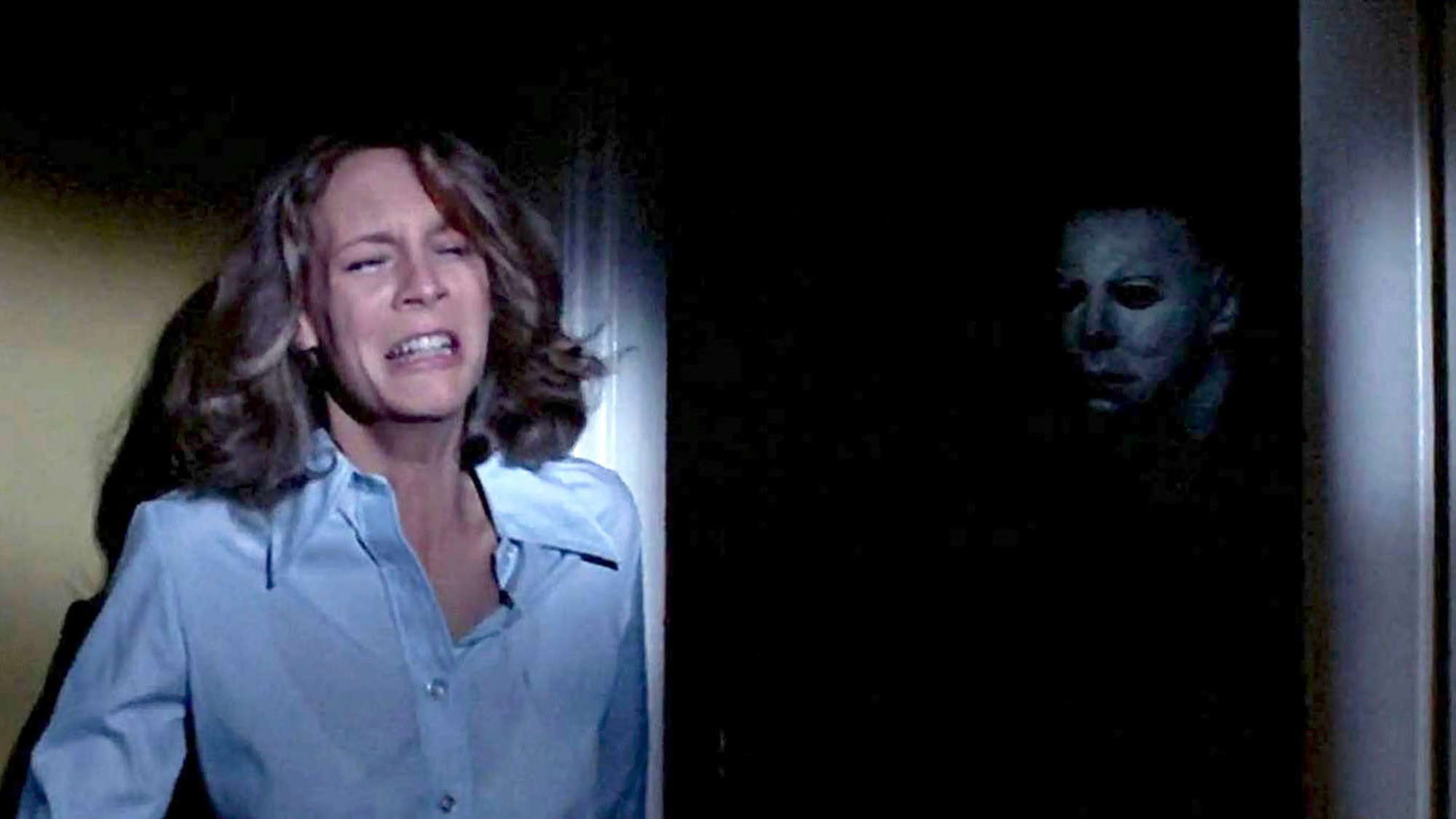

Soon after, Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978) locked in the template, with its own masked killer: Michael Myers –sparked by Carpenter's visit to a psychiatric hospital, where a 12-year-old patient's empty stare struck him as "pure evil". The film also centered a Final Girl who was, notably, a scream queen: Jamie Lee Curtis –daughter of Janet Leigh from Psycho.

This terror felt closer than the Gothic '60s: cities and farm towns you knew; monsters who were once human; violence dealt with everyday tools –a kitchen knife, a chainsaw. One last era-specific grit would fade as the '80s arrived.

The New Pop Monsters

Friday the 13th (1980), Sean S. Cunningham's riff on Halloween and Psycho, cemented the formula. Jason Voorhees –who fully emerges in Steve Miner's sequels– kept the pattern: masked (since saga's third part), mostly mute, killing with machetes and whatever's at hand, and always chasing teenagers. That last bit became central to the franchise and the slasher at large.

In the lore, Jason drowns at a summer camp while distracted teen counselors were off "sinning". Punishment follows –first via his mother, Pamela Voorhees, then via a resurrected Jason– across eleven horny-teen body-count movies.

As the series grew, teens who partied, drank, or had sex were slaughtered –moral beats straight out of EC Comics. Deaths got bloodier and more inventive, thanks to FX maestro Tom Savini. Friday the 13th proved the Halloween formula could mint hits on small budgets –fueling a glut of '80s slashers, supercharged by VHS.

Amid the wave, don't skip My Bloody Valentine (George Mihalka, 1981) and The Burning (Tony Maylam, 1981) –a spiritual offspring of Friday the 13th and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. The era's hidden gem is Sleepaway Camp (Robert Hiltzik, 1983): a raw bootleg-feeling riff with an early POV-killer angle and one of horror's most jaw-dropping endings –rough acting and all.

Another '84 release, The Terminator (James Cameron), borrows slasher DNA: an unstoppable, single-minded killer stalking Sarah Connor. Had the sequel not pivoted to super-action, the cyborg could've joined the monster pantheon on sci-fi grounds.

Then the pendulum swung. After a run of mute, relentless, human-scale killers (zombified Jason aside), Wes Craven unleashed a charismatic loudmouth whose quips almost made you forget the child murders: A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). As the saga rolled, Robert Englund's Freddy Krueger added charisma to carnage, razoring teens with that clawed glove.

The first, darkest film frames Freddy as a child killer burned alive by vigilante parents. He returns as a demonic presence invading dreams. Without leaning hard into the occult, the premise echoes the era's Satanic Panic: teens attacked where parents can't protect them –inside their nightmares.

Freddy went full pop icon: seven films and a TV series in a decade. MTV-grade irreverence cracked the door for other quippy monsters –most notably Chucky. In Child’s Play (Tom Holland, 1988), serial killer Charles Lee Ray transfers his soul into a doll. Like Freddy, the supernatural hook returns, along with the classic the kid is right but no one believes him.

The Rules of the Game

When the well seemed dry, Craven returned with the anti-Freddy: Scream (1996), a slasher about slashers that reset the rules. A cast of ascendant '90s stars, grunge-to-boy-band aesthetics, and Ghostface –the most human of the pantheon–stalking teens with a razor-keen knife.

Driven by revenge and madness, the killer ritualized the hunt –calling first to toy with victims: "What’s your favorite scary movie?" In the landline '90s, prank calls weren't rare, and that disembodied voice felt like an intruder in your home. I remember a spell like that as a kid; it rattled my parents for days.

Craven made a meta movie –peppered with nods to his own work– that literally spells out the slasher rulebook in one of horror's most important talky scenes. Across the saga, Scream kept adding rules that now shape not just slashers but horror at large. Here are the core three from the first film:

Rule #1: Don't have sex –original sin gets you killed.

Rule #2: Don't drink or do drugs –altered states get you killed.

Rule #3: NEVER say "I'll be right back" –or go investigate alone. Death sentence.

A New Pantheon of Horror

Ghostface was the last to join a club now crowded with Leatherface, Michael Myers, Jason Voorhees, Freddy Krueger, and Chucky. For forty years they've defined screen fear, replacing the original Universal Monsters –Dracula, Frankenstein's monster, the Wolf Man. Pop culture turned them into cross-media personalities.

Industrialized production turned sagas into franchises –most boasting ten-plus entries including remakes that still roll out today. Around them swirls an ocean of merch and collectibles: action figures, comics, video games, even Mortal Kombat cameos. Freddy had a rap single –and yes, a 1-800 hotline.

Even with Scream's jolt, the 2000s were rough –copycats and limp remakes. Some "so-bad-it's-fun" entries endured (Jason X, Freddy vs. Jason). Closest to recommendable: Rob Zombie's House of 1000 Corpses (2003) –slasher-adjacent in grindhouse clothing, much like Hooper's original Texas Chain Saw.

The Slasher in the A24 Era

The 2010s leaned back into the paranormal and art-horror aesthetics –A24 became shorthand– while outright parodies popped up (Final Girl, 2015). From 2020 on, we've seen solid returns: Scream (2022) and Scream VI (2023) from Tyler Gillett and Matt Bettinelli-Olpin, plus Halloween Kills (David Gordon Green, 2021). Among the legacy revivals, these are the safest bets.

Ti West's X (2022) pays perhaps too direct a homage to Texas Chain Saw, but wraps it in the polished "elevated horror" aesthetic. Not my favorite, yet it puts core slasher pieces back in motion –and, for better or worse, inspired a wave of follow-ons.

If we're drafting a new monster club, the current king is undeniable: Art the Clown from Terrifier. The indie saga –now three films and counting– went viral on ultra-gore audacity, reviving the old let's see if you can handle it ritual. Art blends silent resilience with wicked clown charisma –equal parts laugh and gag reflex. Terrifier helped spark a mini-revival spanning public-domain splatter like Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey 2 (Rhys Frake-Waterfield, 2024) to experiments like In a Violent Nature (Chris Nash, 2024), which restores the killer's POV.

A Marathon for October 31

The slasher reshaped horror –from scripting to shooting–squeezing every dollar out of lean budgets. Clear rules kept it recognizable as it morphed to stay current. Once mainstream, now niche again, its monsters shilled in ads and turned up at events like rock stars. That pantheon is past tense; a new one isn't quite formed, though you could imagine Annabelle, Art the Clown, and… who else?

A starter stack for pizza night: Halloween, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors, Friday the 13th Part VII: The New Blood, Scream, Child's Play (Chucky), and Terrifier 2. It's October 31 –ready for that slasher marathon?