In JLA/Avengers (or Avengers/JLA), the greatest crossover between superhero universes ever published, there's a telling scene. After the Avengers visit the DC Universe and the JLA visit the Marvel Universe, the two teams finally meet –and Superman delivers the following value judgment about the Marvel crowd: "Your world may be a sad and shameful disaster, but you're not bringing your madness to ours too!" Captain America fires back: "I knew you were fascist tyrants –this just confirms it!".

In that exchange –masterfully condensed by Kurt Busiek and George Pérez, the GOATs– you can hear the fundamental spiritual difference between the two: in DC, heroes are adored; the universe is bright and orderly, but that order also hides a deeper control –a world in which heroes are part, whether they like it or not, of a machinery of domination, of the establishment. In Marvel, meanwhile, heroes are outcasts, outsiders, people working against the establishment. That gives them more freedom and independence, but it also makes their universe more chaotic, because there's no real synergy between superpowers and the powers that be.

Freedom versus securitization, round a million.

A Cosmological Excursus on DC and Marvel

This philosophical difference between Marvel and DC has a cosmological counterpart. Cosmology is the history of universes: the study of their origins, cosmic forces, dynamics, and speculation about their end. It's often paired with a cosmography: a graphic representation, a map so you don't get lost. Cosmology is a serious science that brings together physicists, philosophers, astronomers, and metaphysicians –but here what we care about is the good stuff: cosmic imagination put in the service of narrative, the chance to invent origins and scales of power with no real-world parallel. Turning origin, ending, destiny, and infinity into beings made of paper, ink, and imagination. A metaphorical answer to the real questions we still can't answer.

The DC Universe

The cosmology of the DC Universe is a mess. It's a patchwork quilt made from scraps of many people's ideas, forged in radically different historical contexts, with wildly different –if not outright opposed– interpretations of what good and evil are, and of what the work they were producing even meant. The DC Universe is overcrowded with Earths, cosmic beings whose hierarchies are constantly reshuffled, and origin stories rewritten every five minutes. Still, above it all, you can reduce the whole thing to the oldest story in human history: good versus evil, light versus darkness.

In the beginning, all there was was the Great Darkness inhabiting the primordial void. Over time, the Light appeared (also known as "The Source"), and it grew and grew until it challenged the Great Darkness for space. The Great Darkness screamed and withdrew for countless millennia. Then the Source created the Hands –its cosmic agents– who initiated the Big Bang. Among the Hands, the most important was Perpetua: a cosmic being who assigned different regions of the Multiverse to her children –Matter to the Monitor, Anti-Matter to the Anti-Monitor, and Dark Matter to the World Forger, who was tasked with creating new worlds out of the dreams and nightmares of the Multiverse's inhabitants. The stable ones ascended and integrated into the Multiverse. The ones that twisted and turned dark were devoured by his dragon, Barbatos. Perpetua grew corrupt and amassed power, forcing the Source to exile her and create the Source Wall: a barrier surrounding the Multiverse, meant to prevent incursions like that.

But the DC Universe also has the Endless –embodiments of certain ideas, like Dream, Destiny, and Death. And it also has a God fairly close to the Old Testament model, who created the Spectre to serve as His Spirit of Vengeance, and who exiled Lucifer Morningstar to a hell very much in the tradition of Milton's Paradise Lost. Beneath all of that sits the Fourth World: Jack Kirby's Shakespearean-cosmic addition, dialectically split between Apokolips and New Genesis, Darkness and Light. Just as with Moore, Kirby's contributions –initially marginal– would become central: the Source is a Kirby concept, as is Darkseid, ruler of Apokolips; the embodiment of control and the vulture of human depression, the voice that whispers in your ear that you're worth nothing and you should just surrender to someone else's domination.

So in the DC Universe you get abstract concepts –ultimately semiotically loose– that stand for pure good and pure evil, creation and stasis; metaphysical entities tied to human constants; and a more explicitly Christian notion of good and evil, complete with punishment. Beneath all of it lies the Multiverse, endlessly destroyed and recreated: sometimes mapped clearly, other times an infinite, shapeless chaos. Superheroes in the DC Universe aren't scientifically overdetermined; they're the product of that formless creative energy running under everything.

The Marvel Universe

The Marvel Universe, for its part, has a more compact cosmogony, because it was built by a much smaller set of hands –basically Stan Lee, but above all the visionary minds of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, plus a handful of '70s creators like Jim Starlin, Steve Englehart, and Roy Thomas. In the beginning, each Marvel Universe is born from the death of the previous one. The current one is the eighth iteration. At the moment of death, each universe expels a single inhabitant, who enters the next version and becomes a cosmic constant. Galan, from the sixth universe, escapes and becomes Galactus, the Devourer of Worlds. Meanwhile, in the primordial magma, immutable cosmic forces take their places: Eternity, his sister Infinity, Master Order, Lord Chaos, and Death. It's a cyclical universe, predetermined in its creation.

The first push came from the Celestials –cosmic entities created by the First Firmament, the celestial being who embodied the first universe, where there was no life and nothing happened. The Celestials rebelled against him, craving life, death, creation, revelry and riot, and they destroyed him.

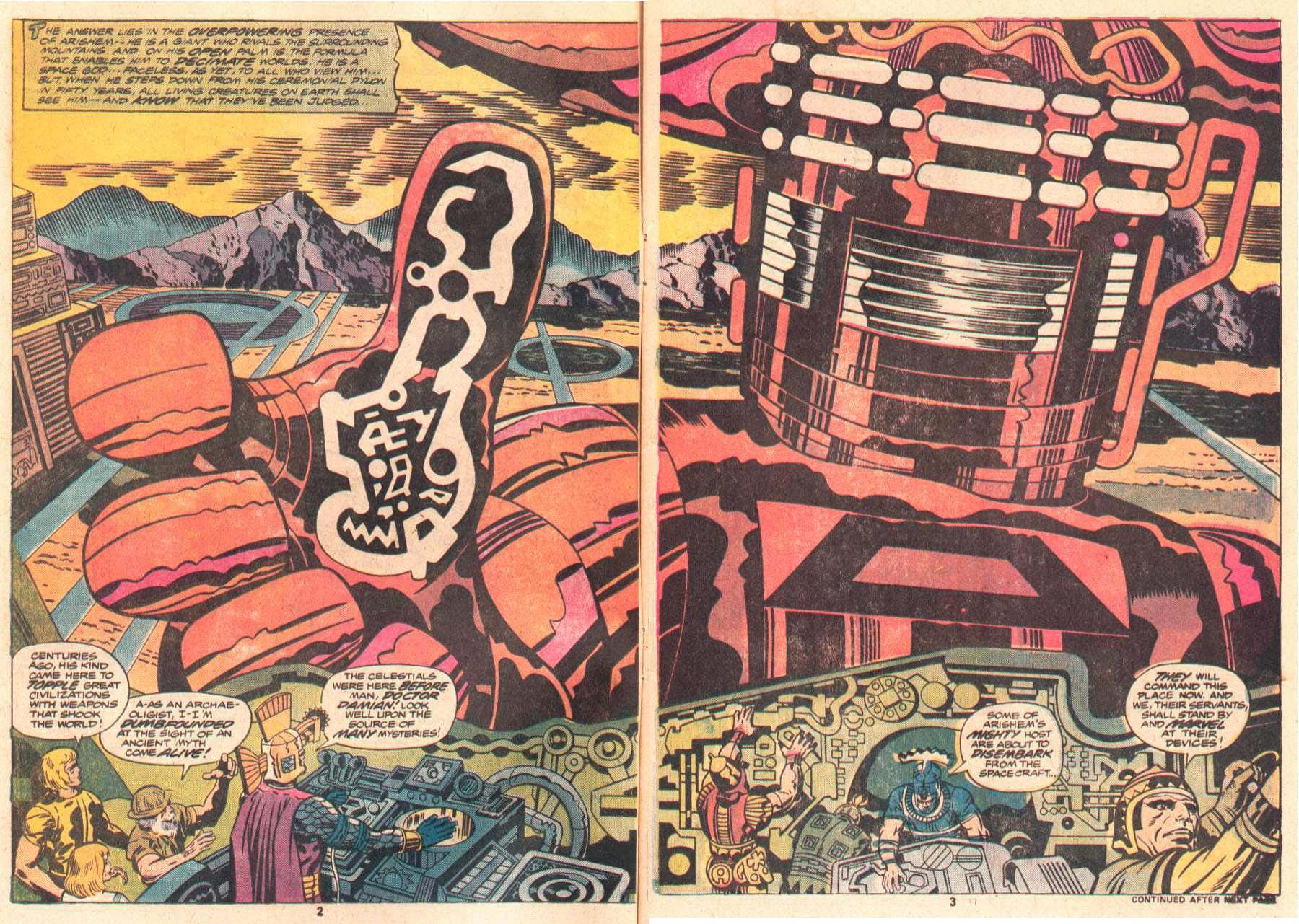

The Celestials –Kirby creations from the '70s– weren't originally meant to plug into the "official" Marvel Universe. They were a concept the Bronx demiurge invented for his quasi-independent series The Eternals. The Celestials are giants inscribed with Kirbytech: those arabesques halfway between mysticism and technology that the King loved to draw. They're the most powerful beings in the Marvel Universe, and they've been coming to Earth since time immemorial, experimenting with it –creating all kinds of living beings, from the Eternals and Deviants to mutants and superheroes. The Celestials are scientists; they want life to evolve. Periodically, they pass judgment: if a world is deemed unworthy, it's destroyed to make room for new forms of life. They are scientific imagination itself –progress and experimentation placed above morality.

The DC Universe aligns more cleanly along the classic axis of good and evil, with the familiar moral architecture of the major monotheistic religions. Paradoxically, its structure is more chaotic and less deterministic, which lets its heroes be more luminous –and makes their alignment with the forces of order harder to question, because the forces of order are also the forces of good. The Marvel Universe, on the other hand, is a universe of explorers, scientists, and tinkerers who experiment with life itself. It's simultaneously more guided and more chaotic, and the morality of creation is less clear: more than once, the Celestials' experiments go wrong, and the free will –and the will to live– of their creations demands rebellion.

This also reflects each company's position vis-à-vis the history of the superhero genre. DC emerged from the primordial chaos of the Golden Age, when creators thought they were making silly fables for children (and soldiers at the front), in which good triumphed and evil was defeated. Thanks to Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, it became the elder statesman of superhero comics: the force of conservatism, reaction, stasis. Marvel, instead, launches the Silver Age with the energy of an outsider on the verge of disappearing, forced to invent something just to stay afloat: in its origin story, it was the rebel company, identifying with college students, anti-Vietnam hippies, and drug users.

Today both are multimedia conglomerates spreading like poisonous stains across humanity's imaginative landscape, processing and instrumentalizing everything –turning it into a version of themselves. And yet something of those old imaginaries persists in their respective comic poetics, in the imagination of their fans, and in the shape of their cosmologies.

Demiurges, the Employees of Imagination

The original Ultimate Universe launched in the early 2000s under Bill Jemas (then Marvel's president), Mark Millar, and Brian Bendis. The concept was simple: classic characters, rebooted from scratch and updated. It was wildly successful; it would send both writers' careers into the stratosphere, create characters like Miles Morales, and decisively influence the MCU. But in 2015 –after 15 years of stories, and caught in the predictable reader bleed of an idea that had once been fresh but had accumulated continuity until it became incomprehensible –Marvel killed it. Only two characters survived the original iteration: Miles and the Maker, an evil version of Reed Richards, both stranded in the main Marvel Universe.

In 2021, rumors began circulating that Donny Cates –coming off an extremely successful run on Venom– was going to relaunch it. But tragedy struck like lightning: Cates had a car accident in 2022 that left him with six months of memory loss, forcing him to abandon the project. Marvel then turned to Jonathan Hickman, who had recently flipped the X-Men inside out as part of his role as the company's "idea man", brought in to revitalize neglected corners of the line.

Hickman returned to one of his obsessions: a group of powerful men running the world from behind the curtain. A channeling of both the Great Man theory of history and conspiracy thinking, in a 21st century where oligarchs and politicians feel ever more distant and aristocratic, and "democracy" seems to do little more than swap figureheads atop a continuous process of impoverishment.

The Maker escapes to a previously undiscovered world, which he perverts by preventing the secret origins of its most famous heroes. Peter Parker is never bitten by a radioactive spider; instead, he's a family man with a harmonious life. Captain America is never thawed. The Fantastic Four are mutated by cosmic rays in an abominable way, causing their deaths. The only survivor –by the Maker's decision– is Reed Richards, whom he tortures physically and psychologically until he becomes the new Doctor Doom. Yes: the guy tortures himself. Meanwhile, the Maker organizes his secret lodge, dividing continents into private fiefdoms, with no input from the people who live there. A still, orderly world without the chaotic action of superhumans –governed with an iron fist. A world more like DC, but powered by Marvel's cosmological principle: experimentation.

DC, for its part, entrusted its new universe to Scott Snyder: the architect behind one of the most successful Batman runs, followed by two massive crossovers, Metal and Death Metal, which expanded DC's cosmic ceiling. He's the creator of Perpetua and the "Dark Multiverse". In general, Snyder's ideas often outpace his execution –his comics can feel stretched and inconsistent– but he found a brilliant, or at least disruptive, anchor for the Absolute line: Darkseid ascends, becomes one with the cosmos, and his essence "infects" a world, turning its heroes into underdogs: a Batman without wealth, a Wonder Woman not raised on Paradise Island by her Amazon sisters, a Superman who arrives on Earth as a teenager and barely knows the Kents. Rot at the root of the world. What's left of heroes when you strip away their role as defenders of the status quo, their golden cradles, their adoration by the masses? A world more like Marvel, but driven by DC's cosmological principle: the struggle between good and evil.

The Poetics of the Multiple

Seen this way, the two launches share a common thread: the idea of a "world turned upside down", controlled by powerful, malignant forces –a power that is both personal, embodied by a handful of overlords, and spectral, because no one is obligated to answer to the polis for decisions made about capital, bodies, and minds. Mark Fisher's famous "there is no central operator". In the Ultimate Universe, this is explicit: the Maker has turned democracy into a forgotten costume, taught in schools as a flawed system. And yet the inciting premise introduces a wedge.

Howard Stark –Tony's father, who in this reality rules the United States– rebels against the Maker and, with the help of this world's twisted Doctor Doom, imprisons him inside the hyper-technological city that serves as his base of operations in Latveria. But they can only hold him there for two years, which becomes the universe's gimmick: those 24 months pass in real time in the extradiegetic world. The narrative began in December 2023, and the Maker will emerge in December 2025. That gives the resistance –few and battered heroes– a chance, a window to prepare the revolution. But it also imposes a deadline.

In the Absolute Universe, there's less embodiment than ontology: there's a serpent coiled around the roots of Yggdrasil, the world tree, and that serpent is Darkseid. Everything feels ominous –the heroes isolated, the big corporations in the villains' hands.

That difference in how they approach two superficially similar concepts shapes the outcomes. On Absolute Earth, you can feel a riskier aesthetic principle at work, built around firmly established creative teams given a wide leash: Scott Snyder and Nick Dragotta on Absolute Batman; Kelly Thompson and Hayden Sherman on Absolute Wonder Woman; Jason Aaron and Rafa Sandoval on Absolute Superman; Deniz Camp and Javier Rodríguez on Absolute Martian Manhunter; Al Ewing and Jahnoy Lindsay on Absolute Green Lantern; and Jeff Lemire and Nick Robles on Absolute Flash.

Sandoval, with colors by Ulises Arreola, draws in a fairly "realistic", even grim-and-gritty mode: muted palettes, anatomically precise bodies, and an overabundance of weapons, tanks, and military tech. The other artists, though, push into less conventional lanes for modern superhero comics. Nick Dragotta sets the bar with a hypertrophied Batman and villains with impossible limbs, elongated faces, and monstrous bodies –like a funhouse-mirror version of anatomy as understood by Burne Hogarth. Hayden Sherman is pure preciosity, with elaborate page compositions that recall the visual logic of Greek ceramics. Javier Rodríguez is an explosion of flat colors and clean lines, a psychedelic garden where words, colors, bodies, thoughts, and memories coexist on the same graphic plane –which is also the plane of the mind. Jahnoy Lindsay is perhaps the most initially disappointing, thanks to compositions that seem stripped down and at times lightly sketched –until you realize he's leaning into a manga register: all action, kinetic lines, bodies built around movement. Finally, Nick Robles alternates between tight, boxed-in page layouts where Wally West's teenage anguish takes center stage, and open, dynamic layouts where the force trapping him becomes both escape and curse.

Overall, these graphic approaches feel new –standing out for their page design, color logic, dynamism, and bodily distortion. And that carries into the stories, which are willing to make risky choices, especially in the underlying logics that animate the concepts. The heroes have been re-signified by having to "start from behind", but not just them: the family, economic, and institutional structures that support them are also stripped away. There's no Amazon family; on Oa they're rebels instead of cops; there's no Speed Force; no Flash family; no Kents, no Daily Planet. John Jones, the Martian Manhunter, is the clearest example: an isolated character, unable to speak, full of secrets. His first contact with someone who understands him is with the Martian living in his head –someone he literally can't hide anything from. This re-dynamization of the familiar brings out the nugget at the heart of the heroes that stays the same, while pushing them toward a resilience built from fragments, memories, and identity-inventions made out of parts. Snyder has said that, in this universe, heroes are forces of chaos –spokes in the wheel of the Great Order.

The Ultimate Universe, meanwhile, starts with three strong books –Ultimate Spider-Man, Ultimates, and Ultimate X-Men– but its narrative musculature can feel rigid, devoted to archetypes too iconic to be reshaped at the level of essence. Spider-Man, by Hickman and Marco Checchetto, is unquestionably the line's heart, built around something Hickman is often criticized for: characterization. It's a superhero story, but grounded in relationships –Peter, Mary Jane, Harry Osborn, Gwen Stacy, Ben Parker (alive in this continuity), and J. Jonah Jameson. Adult characters whose problems are more in tune with the reality of fat forty-somethings reading comics now than with teenage life. Ultimate X-Men, by Peach Momoko, lives in a more distant aesthetic territory: a shōjo manga with cute, slightly ultra-deformed characters, moving slowly against a single villain. Momoko's chibi watercolor style –an absolute sales phenomenon in recent years– pairs with a story of high school, isolation, and genetic experimentation.

Ultimates, written by Deniz Camp (the shared creative link between both companies) and drawn by Rosario talent Juan Frigeri, works as the glue that binds the line together, delivering the shock of recognition by reintroducing classic characters in new forms. But at times it seems to carry a vision of revolution that's a bit simplistic –and too optimistic. The launch lineup is rounded out by Ultimate Black Panther, by Bryan Hill and Stefano Caselli, which is a disaster: poorly structured, with events narrated more than shown; antagonists who shift without logic; and nothing meaningful to say about the geopolitical and power dynamics that define the character. More recently, Ultimate Wolverine was added –seemingly more for the character's box-office name than for any genuinely new take.

Against Absolute's graphic and narrative innovation, Ultimate can feel more interested in telling yet another version of the same old stories. Its biggest originality may be structural: it seems to be building toward a superhero story with an ending. Everything suggests that once the Maker returns, the universe will hit its climax in the aptly titled Ultimate Endgame. Who lives, who dies, whether a credible revolutionary climax can be pulled off, and whether Marvel will actually let its current golden goose die –all of that remains up in the air. Snyder, meanwhile, has said he imagines the Absolute Universe running for many years.

There's a famous anecdote in the history of American comics. It can't be verified, but legend –"print the legend", as they say– claims that Stan Lee gathered Marvel's staff sometime in the late '60s to tell them something important. It's easy to picture Lee in bell-bottoms, the last buttons of his shirt undone, chest hair out, dark magnifying shades, a thick mustache, a brown leather jacket, sitting in his Marvel office with a window looking out onto Madison Avenue, using every ounce of snake-oil charm to say this: during the '60s, Marvel had evolved too much. Peter Parker had graduated high school; Captain America had returned and assembled a very different Avengers; Reed Richards and Sue Storm had had a child; Doctor Strange had met Infinity. All of that made the characters harder and harder for the audience to recognize. Lee lowers his glasses, slowly scans the room, and says: "From now on, Marvel doesn't sell change– it sells the illusion of change."

Since then, generation after generation of creators have tried to leave their mark on the same characters, producing a glut of interpretations, remixes, reboots, and younger versions who follow in the elders' footsteps and overcrowd the universe. Four, five, six Robins at the same time. And this tendency has its cosmological counterpart: an increasingly baroque architecture of universes. On one level, at the character level, it sinks deeper into total simulacrum –where the original, Platonic version is no longer recoverable thanks to accumulated continuity and the magpie recombination habits of creators. On another level, cosmology: the multiplication of power tiers and mythical origins tries to put everything in its place amid an impossible proliferation of signs. Ultimate and Absolute are, at once, the latest attempt in a long chain to return to an original Platonism –lost like every paradise–and one more layer in the chain of simulacra.

Move forward by starting over. Accumulate while trying to discard. Renew by returning to basics. The magic and the curse of the superhero genre is its sponge-like solipsism: a genre that continually renews itself in the contemporary moment, yet can't stop talking about itself.