I find it impossible to start this series of articles without going straight to the core of the disturbance, the ground zero of brain destruction, the Alpha and Omega of contemporary cinema. I cannot begin without writing about Akira, the film by Katsuhiro Otomo. I still owe the manga a read.

Akira is inescapable for a whole bunch of reasons, but let's highlight three: innovation, inspiration and impact. It is an innovative film, both in its thematic depth and its cinematic methods. If the quality of its animation still makes an impact today, I can't imagine what it did to the psyche of audiences at the time of its release. In fact, it was the most expensive Japanese animated film of its era (around 10 million dollars) and its production involved so many companies that they had to form an "Akira Committee" to organize the work.

Second, it is a constant source of inspiration for other audiovisual creators, illustrators, animators and writers. Naming them here is unnecessary. But the marks of its influence are everywhere. And third and last, it had an almost global impact from an overwhelming commercial success, becoming a vehicle for anime aesthetics worldwide. The resonance achieved was not only built on commercial success, but its power is linked to an aesthetic achievement. Animation showed that it could be much more than the Disney formula of fairy tales, musicals and talking animals.

These three factors are crucial to understanding Akira as an inescapable reference in our canon, since the elements it introduces would later become recurrent: animation in the broad sense, manga-anime, science fiction, cyberpunk and weird fiction. Akira shines as one of the cornerstones of this canon because of the quality of its animation, the complexity of its plot and, of course, the trauma of its characters. Let us then dive into what matters: the story of Akira and its thematic structure.

The story of Akira: the Apocalypse as past and future

[Spoiler alert]

Year 1988, nuclear explosion in Tokyo. World War III. Reconstruction. Neo Tokyo. Year 2019. Cyberpunk, high tech low life. Mega skyscrapers, the urban grid become an amalgam of the new and the ruins of the old city.

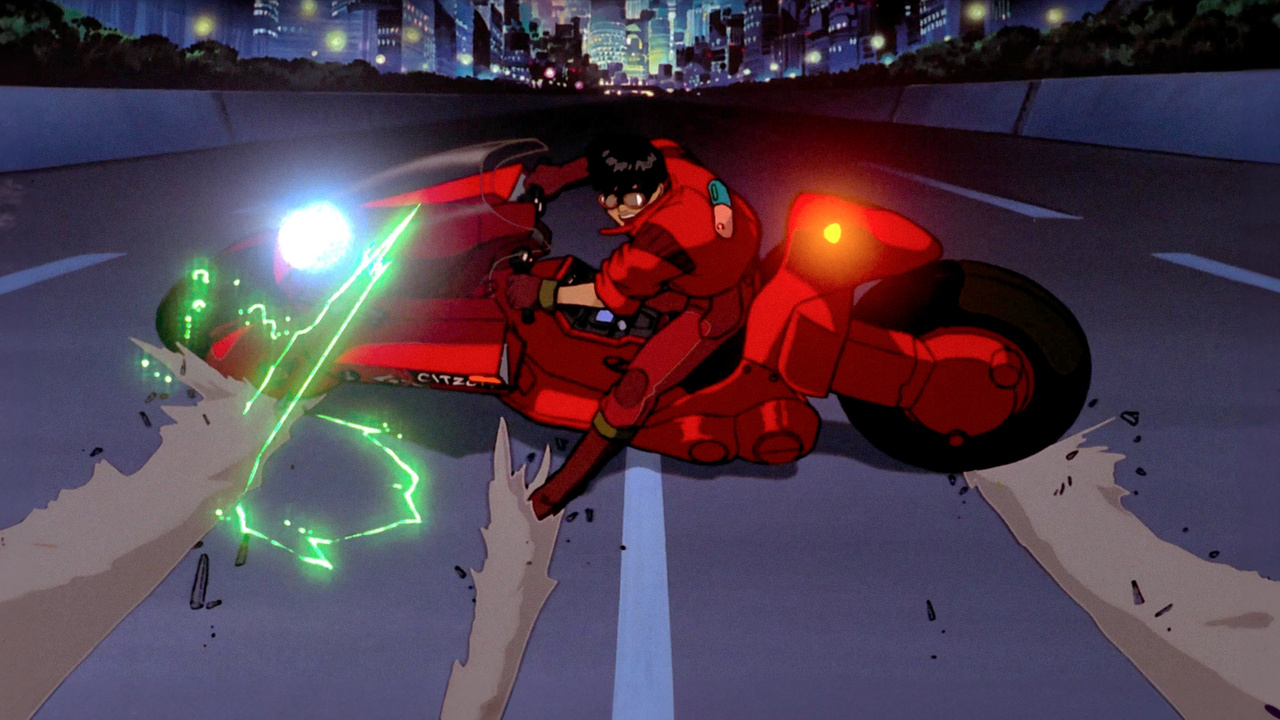

Against that backdrop, a gang of teenage bikers. Drugs, high-end motorcycles, violence. Among them, two friends. Kaneda and Tetsuo. Big brother, little brother dynamic, friends since they were little. Tetsuo is Kaneda's protege, the leader of the gang, who rides the iconic motorcycle (the classic red one from the poster) and plays his role with the nonchalance that only natural-born leaders have.

In Tetsuo there is an inferiority complex. Childhood trauma, socialization problems and a conflicted relationship with his friend, big brother, leader. The red motorcycle, the object of desire. "If I could ride that bike..." he thinks. Throughout the entire film we follow this group of lonely young people, while adults only appear in roles of authority: police, military, politicians and teachers.

Neo Tokyo lives in constant turmoil. The government represses any type of protest and a cult announces the end of days, a new final judgment upon the city rotting in its own corruption. The name of the future executioner is none other than Akira. In between, an insurgent group plays its own game. The government is a council of sclerotic leaders, the old order that Neo Tokyo managed to rebuild after the explosion and the resulting World War III. Everyone plays their cards, but the executive arm of the council is the military and police, which maintain their power through bullets and tear gas.

In the middle of a fight with another biker gang called The Clowns, Tetsuo crashes into a child who looks like an old man. Like a Hasbullah, but with telekinetic powers, who goes by the name of Takashi or Number 26. There, the story splits into two parts. On one hand we follow the course of Tetsuo, who begins to manifest powers that seem to have been transmitted through contact with Number 26. And we also see that 26 is actually one of three children (there are also Number 25 and 27) who have these powers and who are part of a government experiment. The trio composed of Takashi, Kiyoko and Masaru is known as the "Espers," the three children who shared their experimental life under the military wing of the government with the mysterious Number 28, also known as Akira.

The military's pursuit to harness Akira's psychic power resulted in the atomic explosion of 1988 that destroyed Tokyo and triggered World War III. Now, Akira's remains rest in a government laboratory in a cryogenic state, beneath the Olympic stadium.

As the hours pass, the powers awakened in Tetsuo continue to grow while being monitored by Colonel Shikishima, head of the government, and his scientific assistant, Doctor Onishi, fascinated by the behavior of the newcomer's aura, measured through a special instrument.

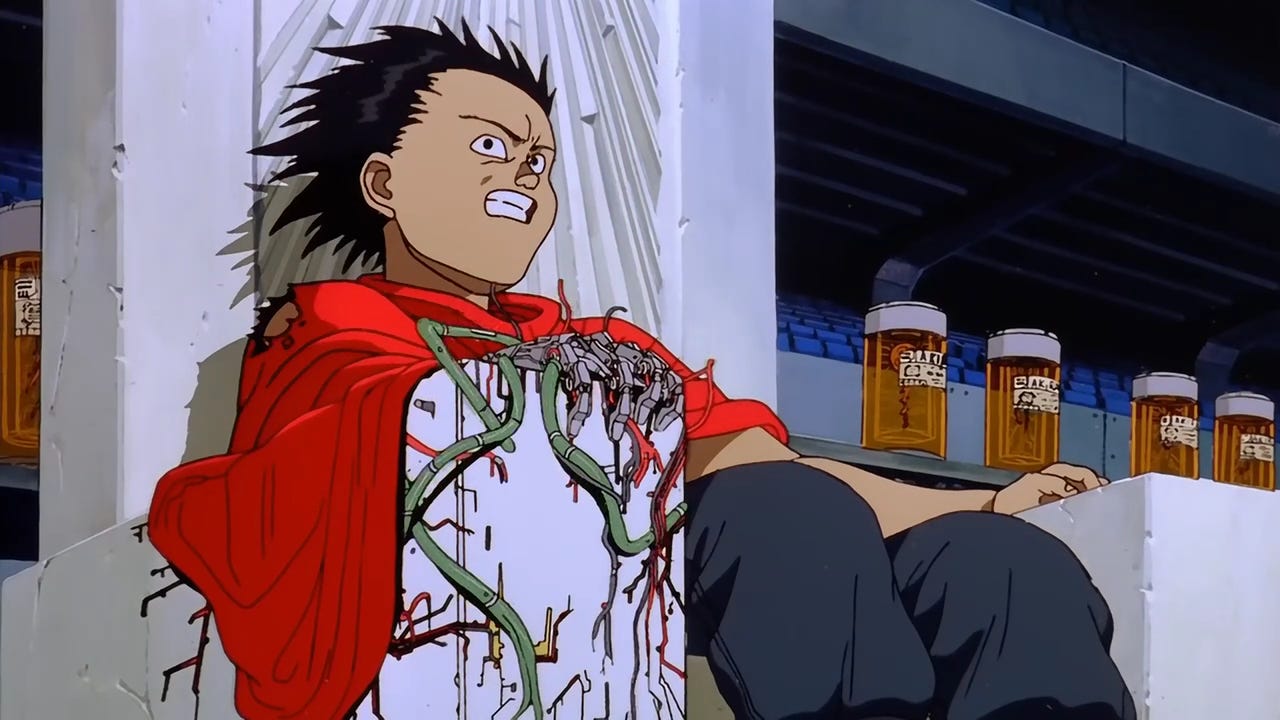

As Tetsuo discovers the origin of his powers, he tries to escape to find the famous Akira, whom he eventually finds after having fought against the entire army. In those attempts to halt his growing ambition, Kaneda also intervenes along with Kei, a girl he met at the anti-government protests who is part of the insurgent group's plot to bring to light the experiments on telekinetic children.

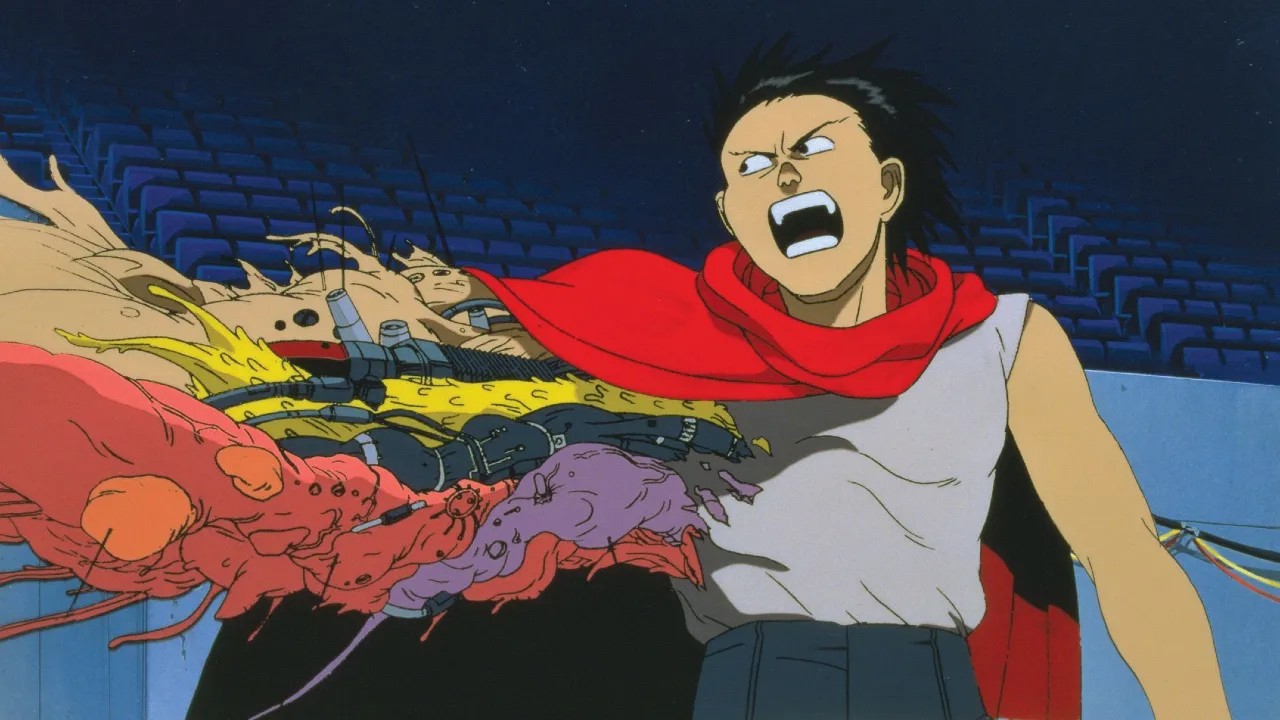

The film reaches its climax when, amid the ruins of the Olympic stadium, and after occupying the stone throne with a red cape like an ancient king/emperor, an out-of-control Tetsuo transforms into a shapeless mass of flesh that grows at a gigantic rate; the three Espers begin one final meditation in front of the jars containing Akira's remains, who makes his stellar appearance to take Tetsuo and the Espers to another dimension. A sequence that releases so much energy that, naturally, it results in a nuclear explosion and indeed fulfills the sentence of a new final judgment upon Neo Tokyo, Japan. The apocalypse after the apocalypse.

What is Akira about?

For many years I asked myself this question. Partly because the first two times I watched the film, I didn't understand it, beyond the fact that I was quite young and what impressed me most was the violence, the motorcycles and the nuclear explosions. I recently watched it for the fourth time, and I think I have some intuition about what it's about.

Akira begins and ends with a nuclear explosion, an inescapable topic in the modern history of Japan and one that permeated much of its subsequent culture. In this story, the nuclear detonations are connected to a supernatural event, they have a character beyond the human, the product of a psychic power out of control driven by techno-scientific ambition. Thus we find, within a story that appears to be science fiction, something of the supernatural, magical, miraculous order.

And, as we can consider, the fantastic (which we hope to define further along in this canon) is, in part, the reintroduction of the religious element in a secularized society. So, if we can think of the supernatural, the fantastic, as an equivalent of the religious, we can also say that the figure of Akira is the figure of divine destruction, that is, of the wrath of God.

This interpretive key, as we will see throughout these articles, puts several important works of Japanese popular culture into perspective, which will naturally be part of this canon. From Gojira to Evangelion we will find this theological element in the form of exterminations, thermonuclear bombs, cities in ruins and eternal refoundations.

God as the face of horror

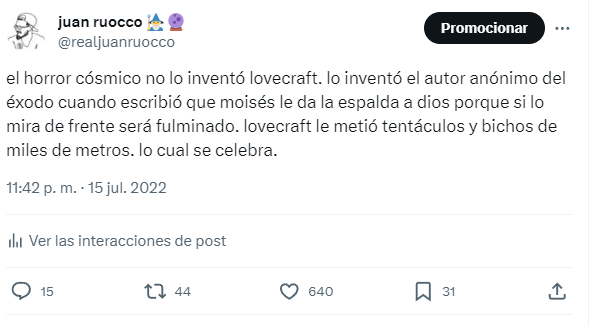

As you already know -- or maybe not -- I am very fond of referencing the myths of the Bible, more precisely those of the Old Testament. Especially the topics of divinity and annihilation as foundational to what we know as the "fantastic genre" and its derivations in horror.

As I state in the tweet, between the myths of the Old Testament and those of the fantastic genre there exists a thematic continuity. That is, in the Old Testament narratives we can find elements of the fantastic. In this case, the divine manifestations follow the pattern of Yahweh/Jehovah, which differs from the traditional image of the Christian God whose attributes are supreme goodness, mercy and forgiveness.

Those of us who are familiarized with reading the Old Testament can appreciate that the images of God were closer to annihilation and absolute terror, more fitting of the imagery of a death metal band than of a religion. Or, better put, of the current common sense that conceives of religion or "spirituality" as compendiums of self-help aphorisms.

It is interesting to consider the first manifestation of God in history: Moses looks at Him, feels terror and cannot look at Him directly, at the risk of dying. In another order of discourse and from modern philosophy, Immanuel Kant would propose that ultimate reality, "the thing in itself" (things as they are, beyond the human gaze/thought), is inaccessible, that we can only see and/or think that which the innate categories of our psychic apparatus allow us to. Centuries later, quantum theory would say that in the universe of particles there are some that remain indeterminate and only acquire a stable form when subject to the gaze of an instrument.

If we understand God as ultimate reality, the absolute thing, that which manifests the potency of all that is real, the entity that condenses within itself the entire universe, that is beginning and end, alpha and omega, that is, an absolute being in its maximum expression, it is coherent that no human could access these manifestations without suffering some type of permanent damage. Horror beyond imagination. God as that which cannot be thought.

Divinity as genocide

But the biblical topics of annihilation and extermination don't end there, with Moses. God Himself will send His angel to annihilate all the Egyptians after having subjected them to seven plagues. He will do the same with the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, and with Jericho.

Destruction, annihilation, mass murder are manifestations of the "angel of God" or "exterminating angel." If we look closely, according to what the Old Testament explains, what irrevocably demonstrates that God is God is neither His love nor His infinite goodness, but the capacity to execute a perfect genocide.

In this sense, we can think of atomic detonations as having a certain religious character insofar as they are manifestations of absolute power. Just as no one could bear to look upon the face of Yahweh without being annihilated, the same can be said of an atomic explosion. The atomic explosion is the equivalent of the face of God in the contemporary era. Atomic bombs function, as exterminating angels, as manifestations of the genocidal power of God.

Akira, as a character, is ultimately the demonstration of that potency. Or conversely, it is his genocidal potency that makes him worthy of being called God, superhuman or supernatural. This reading is justified within the narrative itself, when Akira is identified by the religious sect as one of the signs that will appear at the end of times. That is, within the story, Akira's capacity to subject Neo Tokyo to a final judgment is what grants him divine status.

Is this not precisely what Robert Oppenheimer thematizes in his citation of the Bhagavad Gita?

"Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

Science and Religion

The final appearance of Akira is not only clothed in a religious character but also a secular one. His appearance or return is the culmination of a series of errors, or rather tensions, within Neo Tokyo that lead to the dreaded outcome.

The web of internal conspiracies that put in check an elitist and corrupt system of government, which uses available institutions as means for its own survival, disconnected from what happens at ground level and isolated in the heights of the infinite skyscrapers that adorn the landscape of Neo Tokyo.

Discontent and rebellion are used as a tool in the palace intrigue by Mr. Nezu, one of the worst representatives of the governing bureau, who inflames the insurrection to destabilize the government and seize power. It is the weaponization of insurrection as a tool in palace politics. Meanwhile, the duo: Colonel Shikishima governs the city with an iron fist and is the only political authority with real power, while Doctor Onishi maintains an unbridled ambition to rewrite the rules of science based on Tetsuo's mutations. This successive chain of errors within the government of Neo Tokyo is what ultimately detonates the fragile calm that had been achieved.

In large part, both the first appearance of Akira and that of Tetsuo, which triggers the second appearance of Akira -- another biblical motif, the first coming of Jesus Christ and the second coming, or parousia -- occurs as a result of scientific ambition out of control, this being a narrative element very present throughout the genre almost since its origin in the tale of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, by Mary Shelley.

The classic trope of "invention destroys the inventor" has its roots in the deepest foundations of the genre and, in a way similar to Akira, is a story at the boundary between what at the time might have seemed like science fiction, but also with inescapable elements of the fantastic genre.

And here we have one of the cruxes of the matter. In Frankenstein, as in Akira, as in Terminator, Jurassic Park and other techno-apocalyptic narratives. What triggers self-destruction? Is it perhaps the price to pay for playing with forbidden forces, as in the case of Prometheus? Should man accept his role in the ontological scale and not attempt to wield elements that exceed him? While it is true that Frankenstein functions as a cautionary tale about the dangers of science, reading the book reveals that Victor Frankenstein, the creator of the monster, is actually a complete bastard to his creation, denying it human status simply because it is ugly, "abominable" in the doctor's terms.

So, is science, and this idea that the invention destroys the inventor, not a metaphor about a certain abusive form of paternity? Are not the thermonuclear explosions of Akira the price to pay for the ominous task of using a group of children as secret experiments by the government? Is Akira perhaps a metaphor for MK Ultra? Or, if we think about it in a Japanese key, is the atomic bomb a divine response to the inhuman cruelty and crimes against humanity that the imperial army inflicted upon the Chinese population in Unit 731?

It is significant that, toward the end, we find ourselves with the childhood versions of Tetsuo and Akira, coexisting in what appears to be a boarding school. Tetsuo, a newcomer joining that social dimension, where the Espers are also present. At some point, poor Tetsuo found his redemption, in a childhood paradise removed from the suffering driven by the sadistic experimental desire of science. There resonate the words of Number 27 saying that Akira lives inside everyone, only some manage to awaken him. And the final words of Tetsuo, when he says that now he understands and will have to learn to live with these new powers.

What is at stake, then, in this series of narratives? The excesses generated by the pursuit of science as an instrument of power, or perhaps the eternal masculine fear of engendering one's own destruction (Cronus and Jupiter, Oedipus, Diego Maradona?)?

Something of this is also found at the heart of the biblical narrative of Genesis, where God forbids the newcomers from eating of two trees: the tree of knowledge of good and evil, and the tree of life. Whoever eats from the first tree, through the acquisition of the knowledge it implies, will die. That is, death is a consequence of being able to distinguish between good and evil. On the other hand, it is significant what God says to the angels before expelling Eve and Adam from paradise:

22 And the Lord God said, Behold, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil: and now, lest he put forth his hand, and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live for ever.

God expels man not by virtue of his disobedience, but because now, being able to discern between good and evil, he is equal to them. Within the biblical tradition, knowledge is also associated with death and punishment.

Conclusion

What is significant about Akira is that beyond its most well-known elements -- the biker gangs, the cyberpunk setting, the adolescent desolation, the militarism, the repression, the suicidal cults or the atomic terror -- it is also a story that addresses several other issues, such as the power of divinity, apocalyptic cycles, power as a paternal function and a long etcetera.

And while the figure of Kaneda exists in the partial function of the hero, it is not a heroic story in the sense that the final resolution does not depend on the individual action of any of the characters. While Kaneda attempts to eliminate an out-of-control Tetsuo, thus establishing the classic trope of friend must kill friend, the film's ending crystallizes when the Espers manage to invoke Akira from his slumber or "beyond," and he takes Tetsuo and them to another dimension, leaving in the energy exchange a nuclear explosion that is understood to consummate the awaited apocalypse. Here it is also worth highlighting the participation of Colonel Shikishima, who seems to be the only somewhat coherent authority figure in this symphony of destruction.

But by far, what surprised me most in this latest viewing of Akira is the intersection between science fiction and the fantastic narrative, where some of the fundamental elements of the canon manifest themselves, something I had not stopped to think about until writing this article. Perhaps this is a bit what the canon is about: mapping different expressions of the supernatural and exploring the relationships between the fantastic, weird fiction and science fiction.