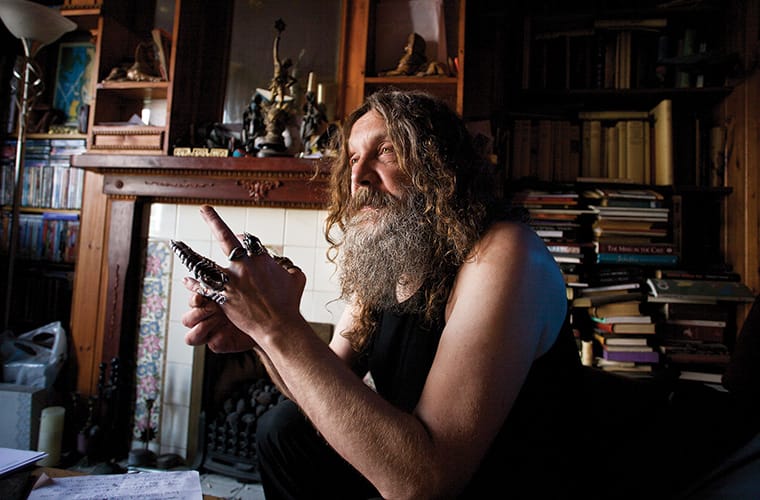

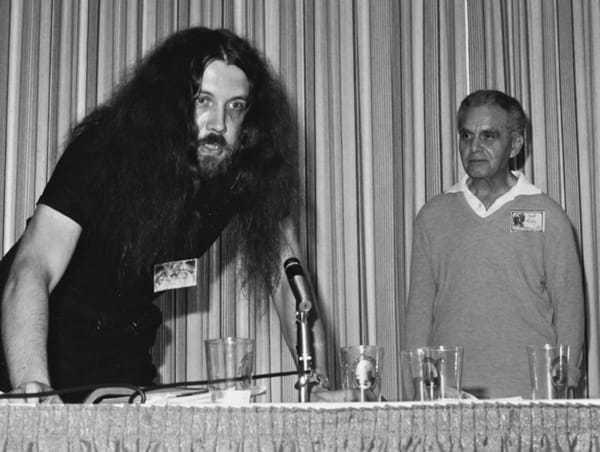

Alan Moore was born on November 18, 1953, in Northampton, England. In the late ’70s he began publishing short strips—mostly parodic and comedic—in music magazines like Sounds and NME. That helped him build a reputation and brought him into the British adult-comics scene. He published work for 2000 AD, Marvel UK, and Warrior, the magazine where he created two of his first major works: Miracleman—an adult retooling of a second-rate superhero comic—and V for Vendetta, the story of a fascist, dystopian England and a mysterious anarchist revolutionary bent on toppling the regime. At 2000 AD he also wrote The Ballad of Halo Jones and D.R. and Quinch.

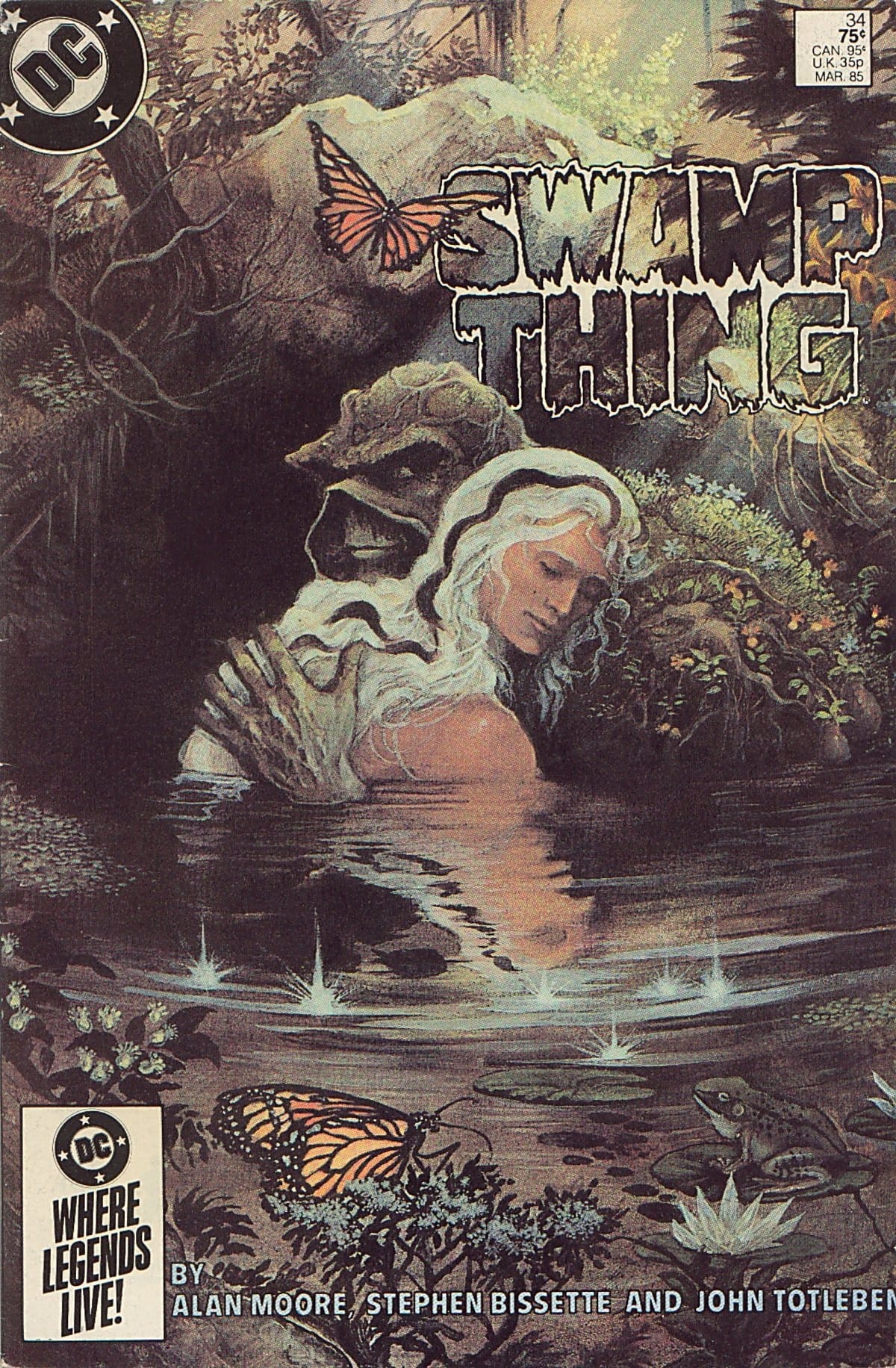

That body of work caught the attention of Len Wein, a DC editor, who hired Moore to write Saga of the Swamp Thing—a generic horror title and one of DC’s worst sellers at the time. The Beard flipped it on its head by his second issue, cementing a retcon that changed everything readers thought they knew: Swampy wasn’t a human brain housed in a monster’s body, but a mutated plant that believed it was human. From there, Swamp Thing became a series where Moore reflects on horror, the United States, love, psychedelia, sex, time travel, and the structure of space—pioneering an approach to neglected characters that would later become a hallmark of DC Comics’ Vertigo imprint.

At DC he also wrote two absolutely iconic Superman stories: “For the Man Who Has Everything” and “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?”, which serves as a closing chapter for the pre-Crisis Superman continuity—before John Byrne’s relaunch—and as a love letter to the absurd, wonderful concepts of the Silver Age. And then there’s The Killing Joke, a controversial and disruptive meditation on the Batman–Joker relationship, with a high level of violence.

However, Watchmen would become both his cathedral and the bone of contention. The book is a diamond of Aristotelian precision: at the time, it was the deepest meditation on the superhero concept, with an extraordinary level of detail, drawn by the great Dave Gibbons, against a backdrop of Cold War anxiety and nuclear paranoia. Moore believed he was publishing a work whose rights would eventually revert to him. But DC realized it had a goose that laid golden eggs—an evergreen book that would never stop selling. And they screwed him over: the rights never came back. Moore, a man of inflexible principles, stopped working for DC and never returned. Like any good secret origin story, that episode helped forge the hatred for the industry that would follow him for the rest of his life.

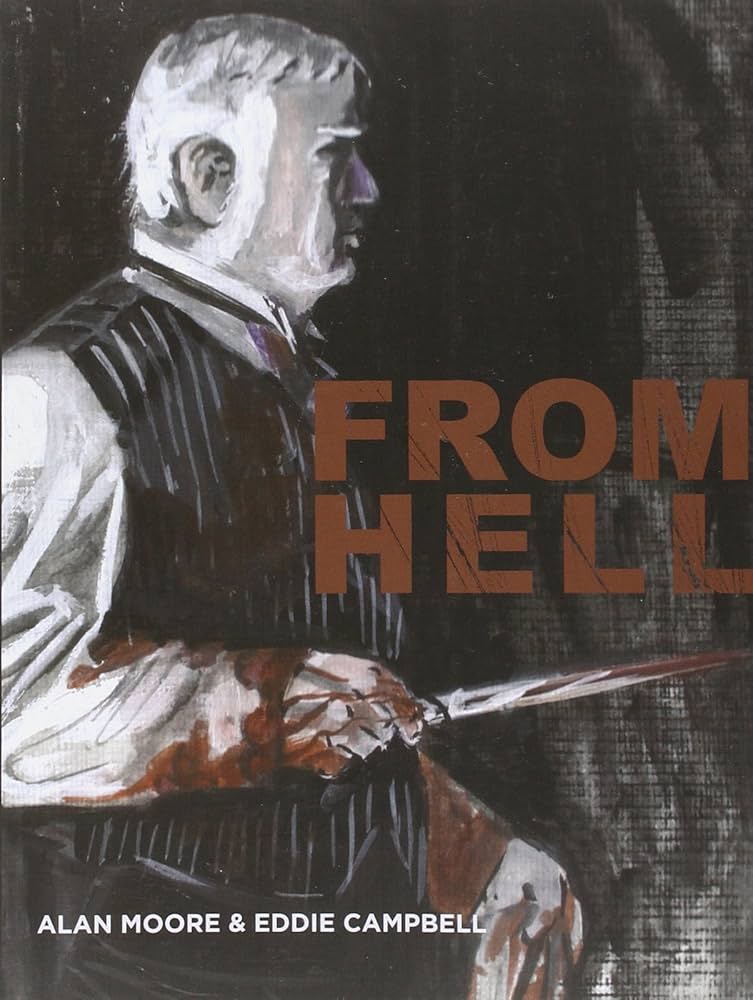

The late ’80s and early ’90s saw Moore retreat to independent publishers, including his own imprint, Mad Love, founded with his wife Phyllis and the couple’s partner, Debora Delano. The highlight of that period was the start of two other major works, both of which began serialization in Taboo, an independent-comics anthology edited by Stephen R. Bissette, Moore’s collaborator on Swamp Thing.

The first, From Hell (with Eddie Campbell), is perhaps the definitive text on Jack the Ripper: a cathedral of psychogeography, occultism, upper-class British perversity, and a vindication of the victims’ history—completed only after a decade of work. The other, Lost Girls (with Melinda Gebbie), is “intelligent pornography,” where the heroines of Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, and The Wizard of Oz meet in a decaying European hotel on the eve of World War I and trade stories of their sexual adventures. Like From Hell, it took years to appear in full, finally arriving as a complete edition in 2006.

The ’90s marked Moore’s return to the mainstream via Image Comics. There he wrote a wide range of projects: the miniseries 1963, a tribute to ’60s Marvel made with several frequent collaborators of that era, including Steve Bissette, John Totleben, and Rick Veitch; a series of miniseries tied to Spawn, Todd McFarlane’s creation; an extraordinary run on Supreme, Rob Liefeld’s Superman clone, which may be Moore’s most purely optimistic superhero statement; and a very strong run on WildC.A.T.s, Jim Lee’s series, where Moore uses the retcon again to propose that the war the characters were fighting—the comic’s very reason for existing—had ended long ago, and that they were like a lost Japanese contingent still fighting for nothing. The results range from mercenary to playful to genuinely excellent, and for a while many readers wondered whether Moore had lost his way.

Then, in 1999, Jim Lee offered him something bigger: his own comics line, with freedom to do whatever he wanted. Moore called it America’s Best Comics and brought in long-time collaborators like Rick Veitch and Kevin O’Neill, while also forming new creative pairings with extraordinary artists such as Chris Sprouse, Gene Ha, and J.H. Williams III. But before long, Lee—one of the comics world’s most enthusiastic company men—sold Wildstorm to DC, the very company Moore had sworn never to work with again, effectively screwing him over from top to bottom.

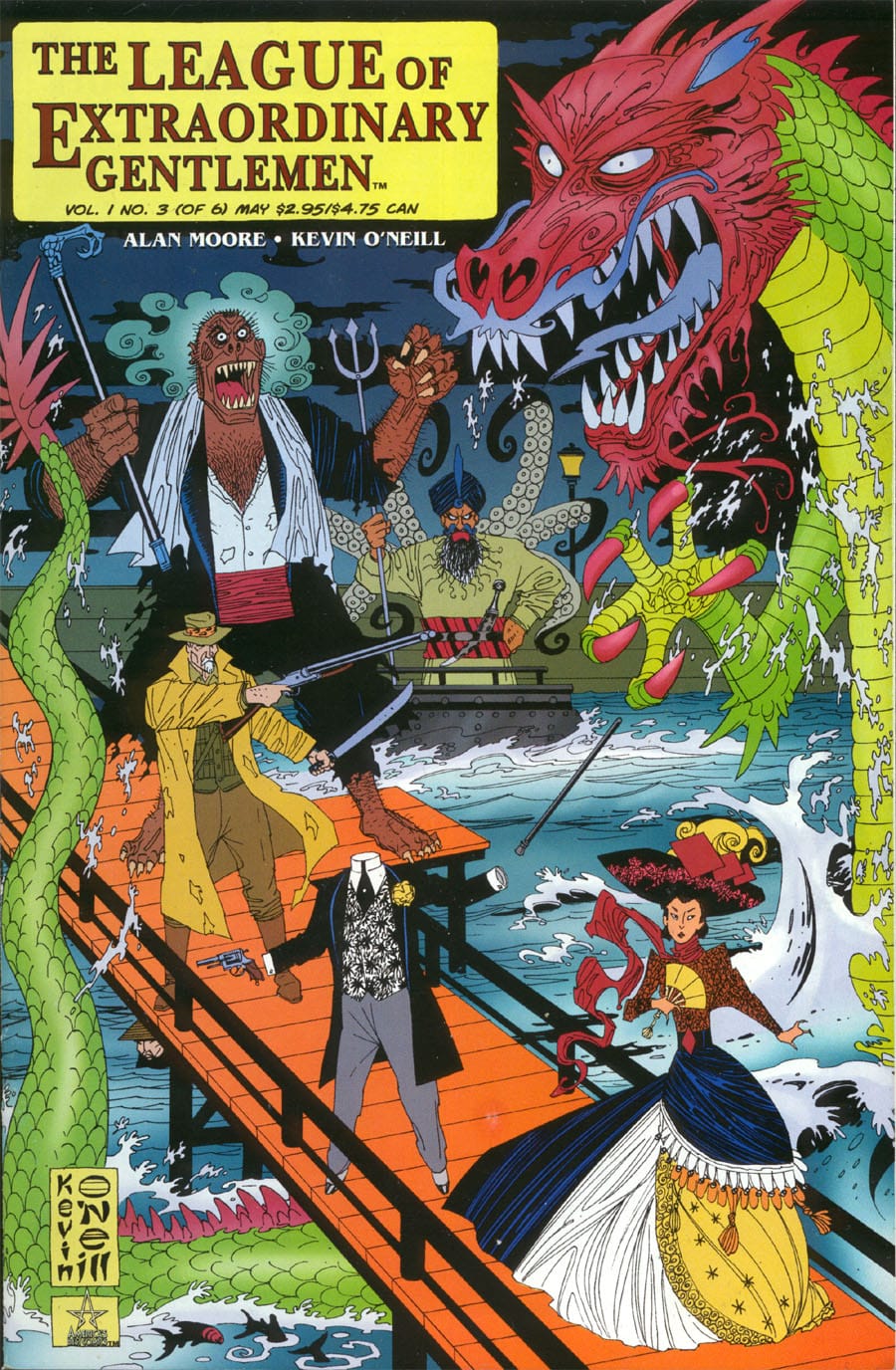

Lee and Wildstorm editor Scott Dunbier traveled to England to calm Moore down, promising he wouldn’t have to deal with DC directly and that DC wouldn’t interfere with his work, and the Beard decided to move forward. ABC became an extraordinary imprint, producing at least four masterpieces: Tom Strong, a pulp superhero inspired by Doc Savage, Flash Gordon, and other precursors of the genre; Promethea, a magical treatise that doubles as a meditation on creation; Top 10, a police procedural set in a city inhabited exclusively by superheroes; and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, a romp through the public domain that also puts into practice Moore’s thesis about the staying power of human ideas and collective creation.

The catch? DC did interfere, censoring parts of Moore’s stories. By 2006, Moore wrapped up the line, took The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen—the one property he fully owned—and slammed the door again.

Moore’s 2010s were marked by dispersion once more: the end of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen; a couple of anthology magazines (Dodgem Logic and Cinema Purgatorio); and a partnership with Avatar Press that produced his last major comics work: a sequence of tribute-and-argument with H.P. Lovecraft across The Courtyard, Neonomicon, and Providence. Those books bring Lovecraft’s racist obsessions and conservative sexual politics to the fore, culminating in yet another apocalypse—one that gestures toward the West’s slow drift to the right.

Since 2019, Moore has been retired from comics. He has focused on his career as a novelist, which began in the mid-’90s and includes enormous works such as Jerusalem. He is currently working on a five-part fantasy series titled The Long London, whose first installment, The Great When, came out in 2024.

The Magus

But reconstructing his career isn’t enough to understand Moore, an author of enormous depth. The following sections highlight some of his most interesting facets.

To start with one of the most important: in 1993 Moore declared himself a ceremonial magician. Drawing on the hermetic tradition systematized and popularized by Aleister Crowley—while adding his own elements—Moore fundamentally believes that art equals magic. Inspired by a line he wrote casually in From Hell (“The only place where gods unquestionably exist is in the human mind”), Moore developed the concept of “Idea Space”: a vast imaginary geography connected to reality through human imagination, where spaces are made of concepts, beliefs, ideas, and systems of thought—territory that an initiate can navigate with training. It’s an elegant, metaphorical answer to the question: “Where do you get your ideas?”

A good explorer can travel there, extract forgotten concepts, or mine under-visited regions in search of the new. That notion underpins Moore’s work on The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and its use of public-domain characters. More broadly, Moore equates creation with magic because both involve manipulating symbols to produce effects in reality. In magic, one prepares physically and mentally, repeats words of power, seeks altered states of consciousness to understand the world in unusual ways, reaches out to higher entities, and tries to get them to “do” something that changes the world according to the magician’s will. In creation, one sits down, thinks, writes, draws, spends long stretches plotting—and then throws the work into the cosmos. There isn’t that much difference between asking Hermes to clear the path to knowledge and creating a fictional character—say, Superman—and then watching how that “work” alters people’s consciousness and reality.

Moore performs rituals, often aided by hallucinogenic mushrooms. He venerates Glycon, a Roman deity who may have been a fraud and whom Moore often describes as a snake made from a stocking. He has also described encounters with the Greek goddess Hecate. While the cult of Glycon began with a dose of irony, Moore has made it real through sincere devotion. His relationship with magic reads as both a tool for inspiration and a way to interrogate reality—to see the world kaleidoscopically, without fixed truths.

Philosophically, Moore also subscribes to eternalism, the view that all times are equally real and have existed continuously for all of existence. Unlike presentism—which holds that only the present is real, that the past is history, and that the future is unwritten, with the “block of the present” moving forward and freezing what was once indeterminate—eternalism proposes that everything has happened and is happening, and that it’s possible to access past and future through ritual and mystical experience. This idea surfaces repeatedly in Moore’s work.

The Resentful

Moore is furious with DC Comics in particular, and with the superhero concept and the comics industry in general. He often says, “I’ll always love the medium of comics, but I hate the industry.” And he has good reasons: it screwed him over, just as it did Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster, Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Bill Mantlo, and countless others. Moore may have thought he was smarter, or that he understood how things worked—but it didn’t matter. Against the corporate Leviathan, its ownership of rights, and its legal machinery, he could do nothing.

He also argues that culture has been infantilized, and that it’s unacceptable for adult men—especially through cinema—to keep consuming superheroes. “Fantasies for 12- or 13-year-olds in the 1960s,” as he puts it. That contempt became fuel for a hard line: he doesn’t allow his name on reprints of his superhero work, he refuses royalties from film adaptations, and he won’t return to the genre. That’s why many books—like Marvel’s Miracleman editions—credit him as “The Original Writer.”

This could be the subject of a longer piece—call it “Why Do We Keep Giving Superheroes Another Chance?”—because Moore is right in one sense, and in another his bitterness resembles that of a jilted lover. That’s why he keeps talking about superheroes, and keeps writing about them—most notably in “What We Can Know About Thunderman,” the long nouvelle at the heart of his story collection Illuminations, which is a direct attack on the industry: a precise act of defenestration. Moore’s relationship with superheroes is a guided missile aimed at the genre’s appeal: both we and he love it because it’s tied to something pure in childhood, to a sense of wonder you can only get then—and that the industry, in Moore’s view, stole from him.

The Anarchist

That links to Moore’s politics. Moore is an anarchist; he doesn’t vote on principle; and he describes modern democracy as what happens when the most powerful and brutal gang seizes the means of governance. This anarchism appears throughout his work in different forms, from the overtly polemical V for Vendetta to the more bucolic (though secretly sinister) Crossed + One Hundred, where he imagines a rebuilt community in a dystopian future populated by humans infected by a plague that turns them ultraviolent.

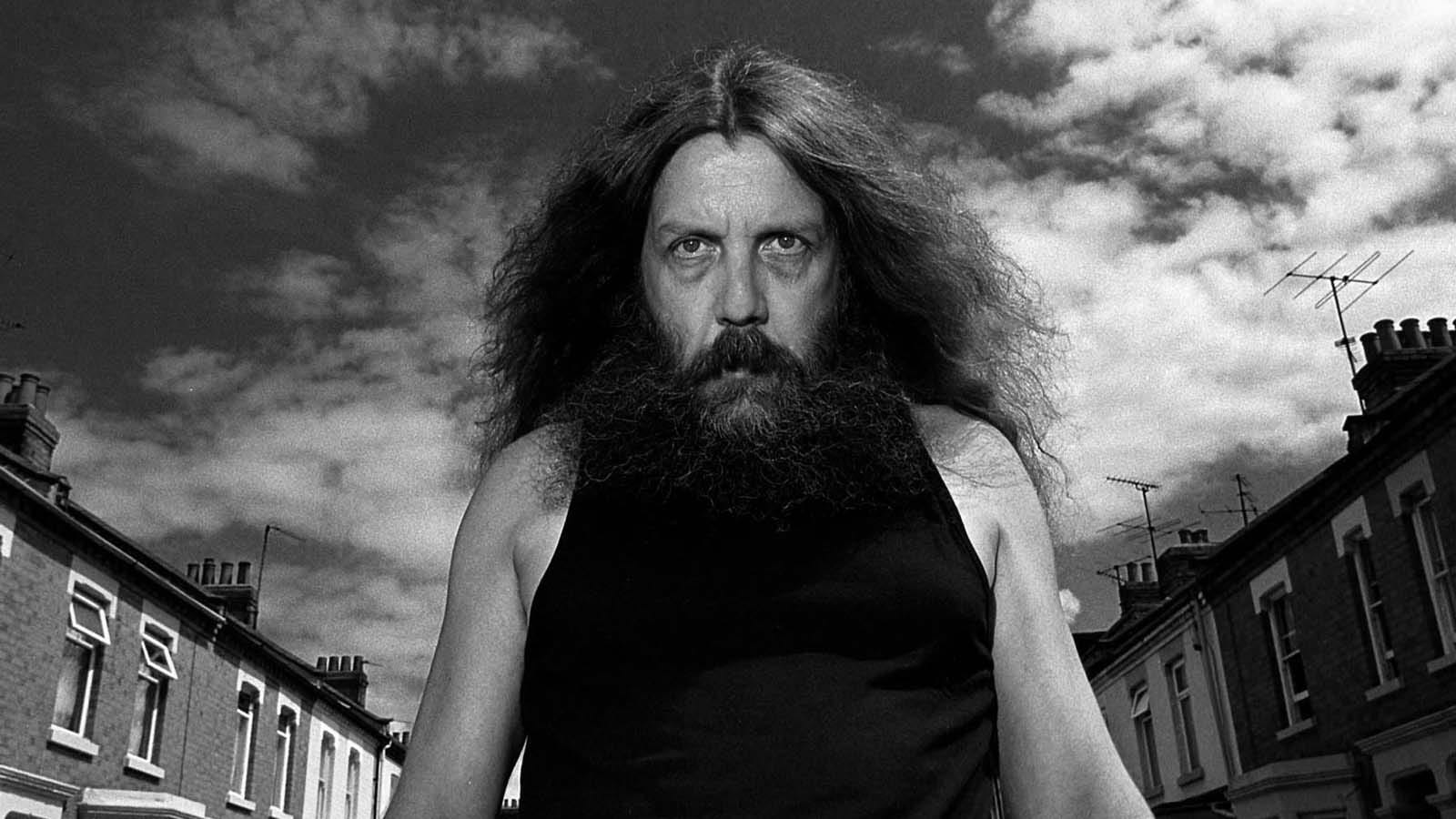

He is also inseparable from his English working-class background: his father worked in a distillery and his mother in a printing business, and Moore grew up in a Northampton area known as The Boroughs—a poor district with high illiteracy and scarce basic services. Moore is a product of England’s public library system: his early education and reading came from there. When he moved on to secondary school—a middle-class environment—he encountered the rigidity of the English class system and its design to keep strata from touching, except in service roles; and how that contact produces a constant feeling of inadequacy, reinforced by upper-class codes that are hard to grasp unless you were raised inside them. He was surprised not only to go from being one of the best students to one of the worst, but also by what he called the “hidden curriculum,” designed to breed obedience and monotony.

Moore never finished secondary school; he was expelled for selling LSD at school. Then he drifted, as his class position prescribed, through miserable jobs—like working at a tannery—until writing became his path out of precarity and toward social mobility. Hence the anger, too: the comics industry stole his surplus value and made him feel small and insignificant in the same way England’s upper classes do to the working class. That’s why his work is full of hatred for the latter—portrayed as sinister, manipulative, insensitive, timid, and unproductive. And it’s why his work is full of apocalypses in which, as in Promethea, the world changes through an understanding that relations of force and hierarchy are degrading and dehumanizing.

The Northamptonian

Moore lived his entire life in Northampton, a tiny English city of about a quarter million people. He never moved; he was never drawn to the big city’s lights; and, as he himself has said more than once, “I never signed up to be a celebrity.” Northampton gives him anonymity and calm, and over time Moore turned the city into the center of his work—a microcosm. Instead of leaving and hating the small town you were born in, Moore makes that town and its quirks the prism through which the whole world can be understood. This is clearest in Jerusalem, a novel set entirely in the city and its surroundings, building an intricate mythology and using modernist techniques to elevate the life of a small town into myth.

The Avant-Gardist

Which leads to the next point: Moore is an avant-gardist working in popular formats. Since the start of his career, his work has tried to bring high-literary techniques—especially from authors like Beckett and Joyce—into comics, satire, and popular art. That’s why Etrigan the Demon, in Moore’s hands, speaks in iambic pentameter, the most famous rhythmic pattern in English poetry. That’s why Watchmen includes a symmetrically composed issue and a meta-commentary in the form of a pirate comic. That’s why the first volume of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century is an extended homage to Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera. That’s why Promethea ends with an issue that can be read as a sequence of splash pages—or taken apart to form a gigantic poster that tells the same story across a uniform space rather than sequential panels. And that’s why Tomorrow Stories includes a strip where each horizontal panel represents a different time, and the narrative unfolds in four simultaneous layers.

For Moore, making comics is an invitation to investigate how comics are built and to find new ways to play with them: open them up like a fish, explore their insides, and then reassemble them into a new form. It’s a reminder that modernism and the avant-garde had a strong element of play—and it points to something we often forget about Moore: his sense of humor and wonder. He seems to enjoy the creative act like few others, and his fascination with writing and comics is ultimately about finding new ways to do something as old as humanity: telling stories.

The Ally

Finally, there is an element of Moore’s career that is as important as it is, at times, contradictory. Moore has always been a writer who brings some dimension of the feminine into his work. In 1983—long before the “Women in Refrigerators” framework and before many of his peers’ abusive behavior became widely discussed—Moore published the essay “Invisible Girls & Phantom Ladies” in Daredevils. There he outlined the depth of gender inequality across society, arguing that men have enjoyed centuries of privilege and are reluctant to give it up; that men are often insecure; and that when they feel threatened, they respond with volleys of contempt and disdain—or refuse to take the issue seriously at all. He then analyzed sexist elements in superhero comics: infantilized female characters; sexually objectifying poses; rape fantasies; and the male gaze everywhere. He concluded by discussing women creators working at the time, while noting that many were concentrated in editorial roles or in the indie scene.

Still, Moore has been criticized for using rape as a plot mechanism across his work: Watchmen, The Killing Joke, Swamp Thing, From Hell, Lost Girls, and Neonomicon all include instances of sexual violence against female protagonists; while Miracleman, Tom Strong, and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen include instances involving male protagonists. Other comics, like Swamp Thing and Promethea, include sex scenes where sex becomes a passage to the sublime. Moore has argued that he could have ignored sexuality the way some contemporaries did—pretending it didn’t exist—but that doing so would have disrespected his project of making comics an adult, respectable medium capable of addressing any subject. More than that, he says it would have disrespected the reality that such acts occur far more often than we want to acknowledge. Writing with blinders on, for him, isn’t writing.