This text could be called "The Revenge of the Analog" due to the resurgence of analog experiences today, partly because of the saturation reached by platforms and that "paralysis" we feel every time the infinite carousel of Netflix appears. In a similar vein, movements like "own your music" and the return of physical media, or simply the pleasure found in not knowing how a photo will turn out until after the roll is finished. All this without considering the rituals that form around choosing a record. It might end up being a passing trend, yes, but it seems interesting that the pendulum may have swung too far towards digital and platforms, so now it's time for a readjustment.

Computing is also part of this revival, although not yet on the same scale as music and photography. It might be striking because few things are as synonymous with digital as computers, and for good reason.

Digitalization is the process by which we capture and convert the great complexity and variety of the world into zeros and ones so they can be handled by the silicon transistors that power computers. But there's an important point to keep in mind: it would be a mistake, unless we actually live in a simulation, to think that the world is binary. What we build through digitalization is a digital model of the world. The advantages of this process are evident: a significant part of the technological development of the 20th century, especially since World War II, was thanks to digitalization, which allows us to accelerate the speed of the calculations necessary to support the infrastructure that surrounds us today.

Another advantage of digital computers is that they are general-purpose: we can program them to simulate practically anything, from the weather and markets to other computers and consoles. How complex the simulation is will depend on the computing power; the more fidelity we want, the more energy and processing power we need. Moreover, Claude Shannon discovered in 1936 that any numerical operation could be performed using binary algebra. This meant that analog computers were at a disadvantage. Digitalization has undoubtedly been one of the great advances of the 20th century, but computers were not always digital.

Analog computers are quite old, with origins that can be traced back to ancient Greece, at the very least. They had an analog device consisting of about thirty gears to determine the positions of celestial bodies, and at least one of them survives, the Antikythera mechanism, which still amazes scientists with its complexity and precision. In the early 20th century, British naval officers used a calculator invented by John Dumaresq that assisted them in calculating shots, taking into account the movement of both their own vessel and the target. Analog computing had its first heyday in the 1930s, with the "Differential Analyzer" built by Vannevar Bush at MIT, which was designed to solve differential equations through integrals. Essentially, it represented the different quantities and variables of equations with mechanical parts, like wheels and disks. By chaining several of these mechanisms together, it was possible to find solutions to complex differential equations, representing the variables and results with mechanical movements instead of numerical calculations. Eventually, mechanical analog computers were briefly replaced by electronic computers, but electronic analog computers are not the same as digital computers.

Today, however, it seems we are reaching the limits in the development of digital computers. One of these limits is the ability to continue miniaturizing transistors to the point where quantum effects start to become a problem: for a transistor to work, an electron must jump from one state to another, and an insulating layer is used to prevent the electron from passing. Now, when miniaturization reaches a certain point, the electron "jumps" the insulating layer, rendering the transistor useless for computation. Analog computers are governed by the same laws of physics, but due to their operation, they could help bypass these limitations.

Unlike digital computers that only work with zeros and ones, analog computers represent and manipulate data using continuous physical quantities, such as voltage, current, mechanical position, or hydraulic pressure. The data that analog computers work with are values that constantly vary, unlike the static binary values of digital computers. This makes them optimal for working with complex systems governed by differential equations or any computation involving rates of change, for example. Unlike digital computers, which require adapting a differential (continuous) model to a digital (concrete) one to perform calculations, analog computers work with the same equations that describe the phenomena under study. This is a significant advantage over digital computers: no conversion or numerical calculation is necessary, as the analog computer performs these calculations based on the same foundation as the equation describing the phenomenon. Furthermore, by working with voltages and currents, they are much more energy-efficient for performing the same calculation tasks as digital computers.

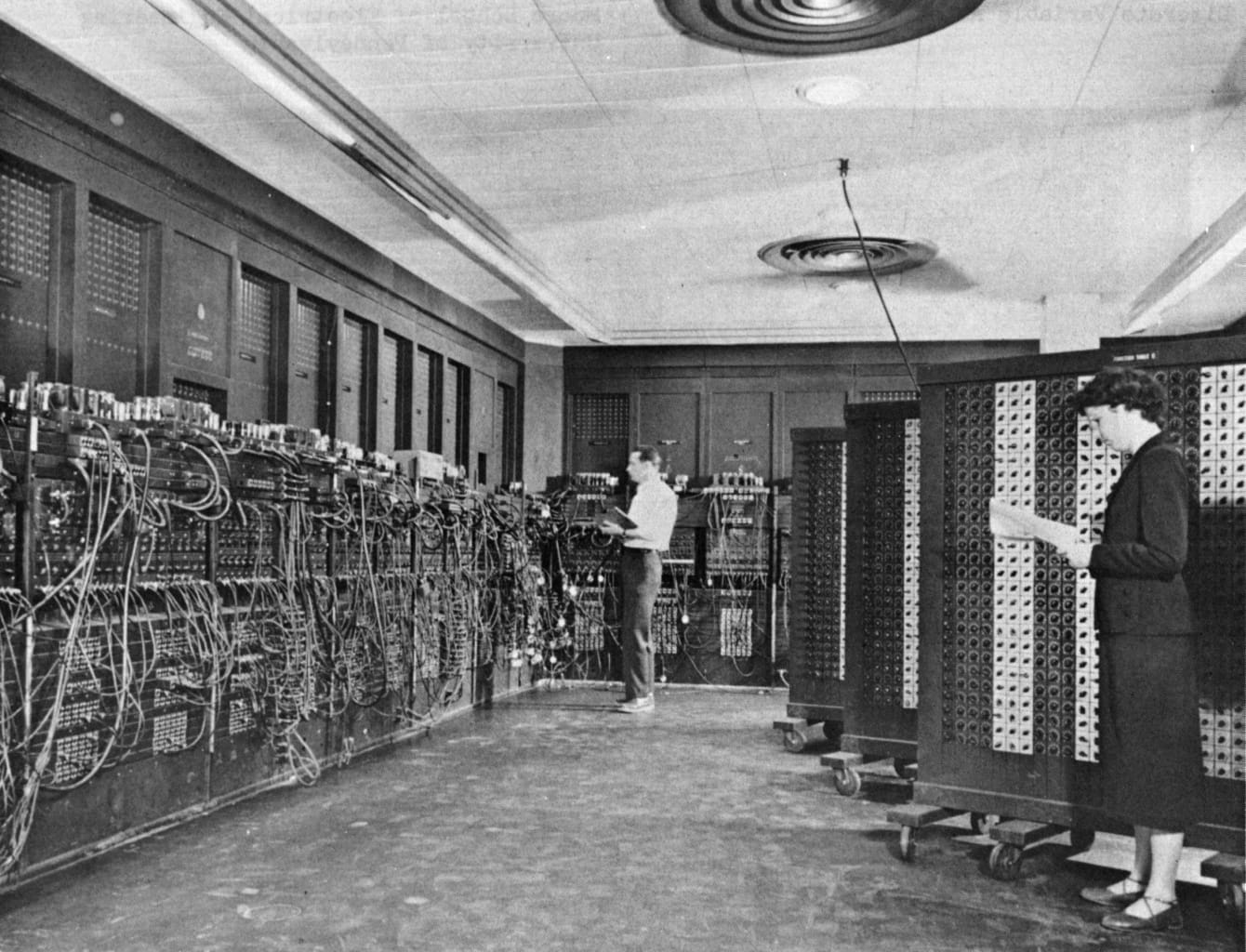

With the boom of generative AIs and chatbots, analog computers have found a promising niche, as they excel in operations like matrix calculations that are fundamental to neural networks. The main goal of the companies leading this resurgence is to achieve miniaturization similar to what has already been accomplished with digital computers, so that something resembling an old telephone exchange with wires and connectors can be the size of a chip.

Perhaps, then, we are witnessing the return of the first computers.

EN

EN