Your grandmother taught you how to play escoba del quince or generala. Your dad and his friends drove you crazy during a game of truco where, no matter what cards you got, they always seemed to have more. You pulled an all-nighter playing TEG with the guys, one of whom ended up leaving after missing ten attacks in a row.

Board games are in the Argentine DNA; they are part of our culture. And far from dying out as a pastime, they keep growing, not just here but all over the world. It makes sense: in the hyper-digitalization of human experience, board games are the contemporary bonfire; a screen-free space for connection, where stories are born, time slows down, and the outside world doesn’t matter. Against the monotony of swipe and scroll and the blunt dopamine engineering of platforms, a board game offers you exquisite tactile sensibility, a challenge that demands your full concentration, and the cognitive freedom that is only possible when you know all the rules of the system (and can even change them).

Board games are also a booming industry. Clearly the little brother of entertainment, but not to be underestimated, with a global market estimated at $15 billion and an annual growth rate of 10%. Approximately 5,000 new games are invented each year, compared to about 500 in 2014. The United States is the largest consumer and creator of titles, followed by Germany, Japan, France, and the United Kingdom in patents, and China in terms of consumption (and surely new games too, but they don’t reach us).

I started designing board games nine years ago, the day after a friend invited me to a gathering at the Faculty of Exact Sciences at UBA. The plan was simple: you showed up at Pavilion 1 and were greeted by a bunch of nerds who brought their games to share. There were no chairs or tables, everyone sat on the floor. There was also no money involved or clear organization, just a beautiful community of fans who loved to get together, with a friendly vibe that welcomed strangers to any game and explained the rules to them. This was perfect for me because I didn’t know any of those games, which were, of course, modern board games.

The Renaissance of Board Games

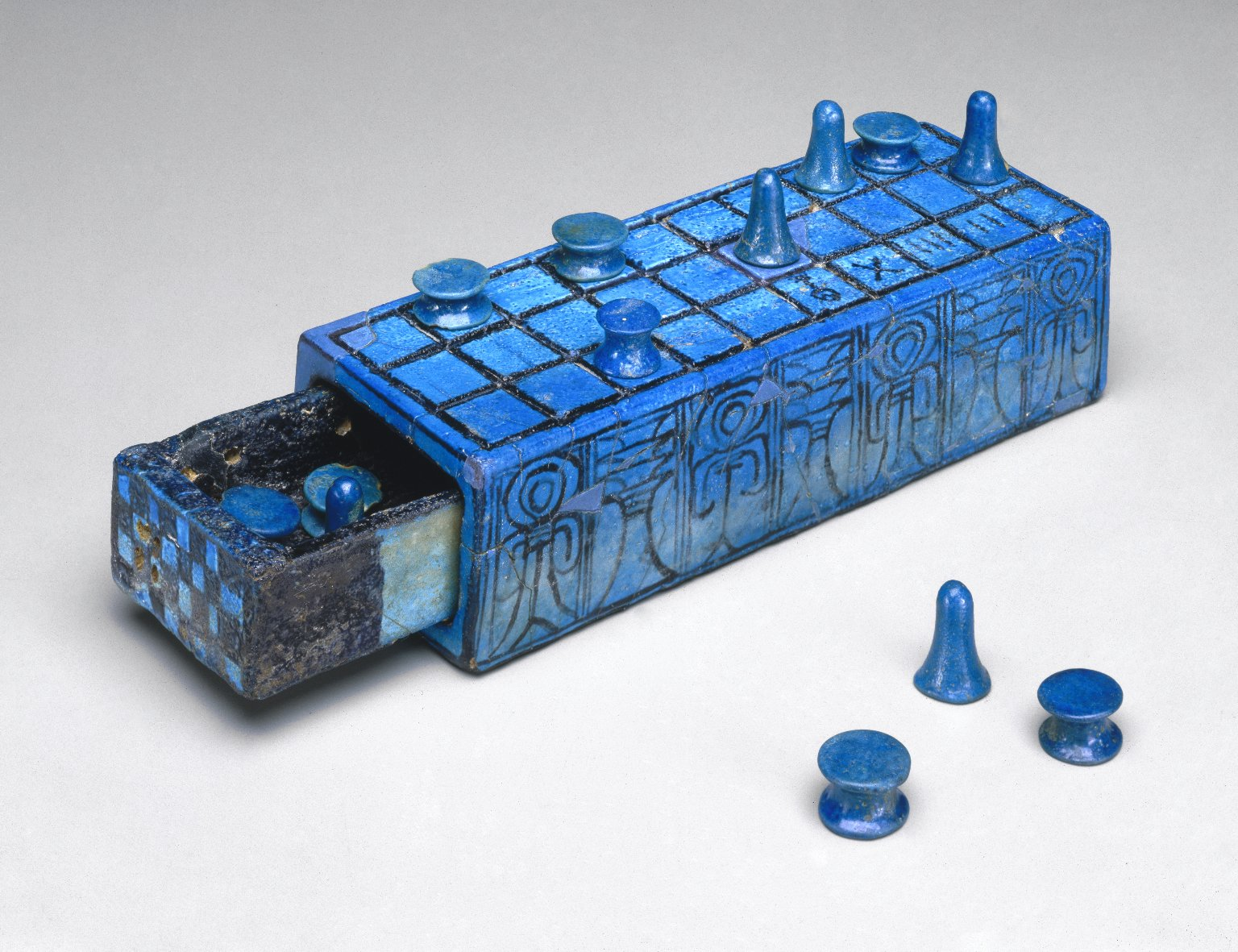

Board games have existed for at least 5,000 years, but those circulating today can be divided into three historical-commercial categories. There are the popular ones, lacking an individual author, played with universal components (like dice or traditional playing cards) and whose rules are passed down orally and modified vernacularly (or, in some cases, there are organizations that codify and sanction them, like FIDE for chess).

Starting in the 16th century, board games began to be manufactured and marketed with brands, one of the first being The Game of the Goose. We now call these games classics, and many are based on a mechanic called roll & move (present in Monopoly or Snakes and Ladders), meaning you roll a die, move based on the result, and something happens when you land. A very simple mechanic that offers no decision-making but generates a lot of joy and frustration thanks to alea, the surrender to luck, one of the four experiences with which Roger Caillois classifies games in his bible Les jeux et les hommes (1958).

In the second half of the 20th century, drawing from various European and American traditions and based on the capitalist need to design new products and reach new audiences, modern design games emerged. The goal was to cut the total dependence on output randomness, that is, the luck that determines the final outcomes of our plays (as happens in many classic games) and instead exploit input randomness, a kind of luck that we can twist. Like the resources produced each round in Catan: no matter what you get, you can accumulate them, build, and even negotiate. Your turn doesn’t end with luck; it only begins there.

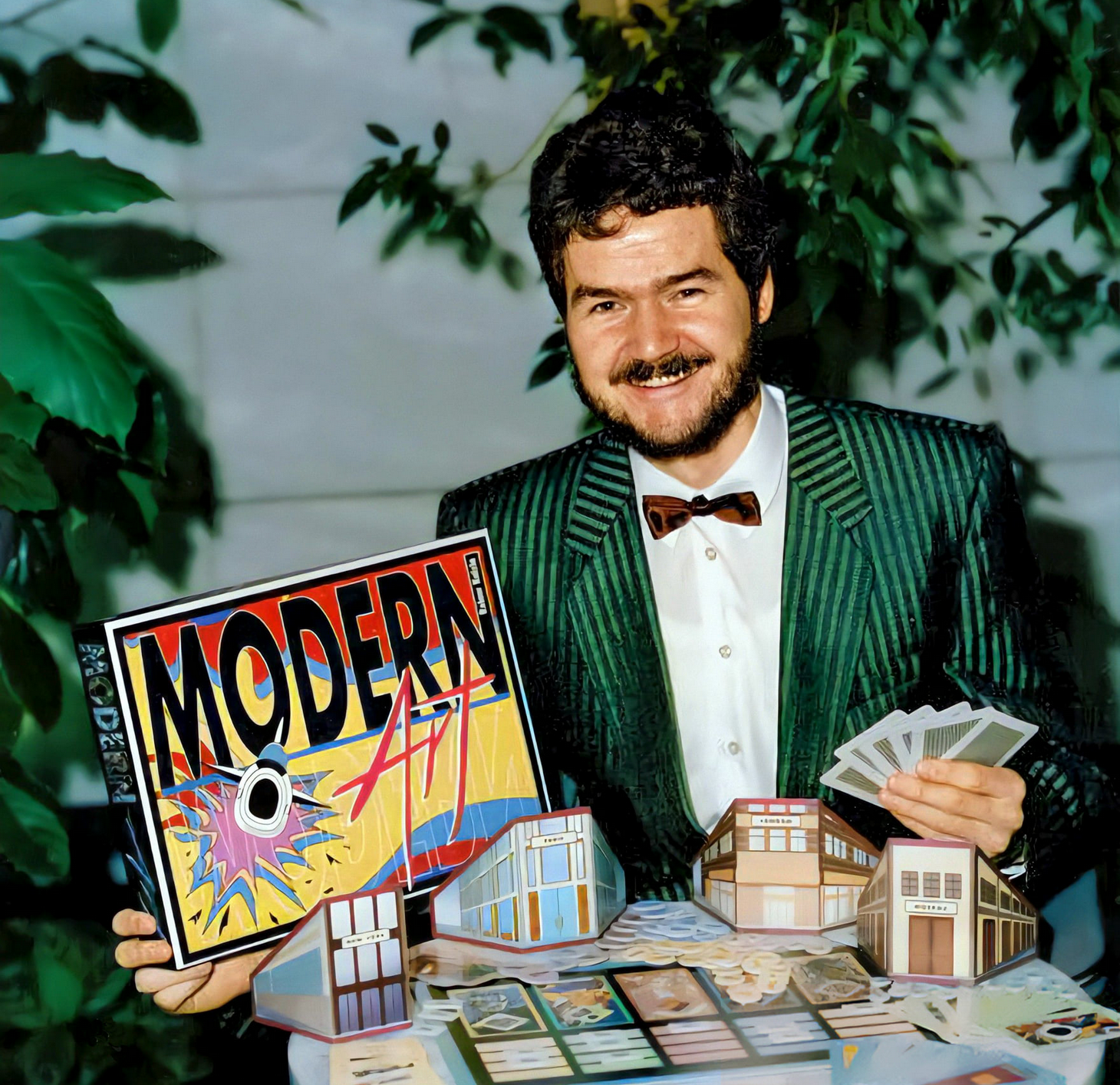

Catan —originally Settlers of Catan— was published in 1995 and shook things up. Its worldwide popularity paved the way for many games that were already making waves in Germany and France —Modern Art (1992), El Grande (1995), Tigris and Euphrates (1997)— to hit it big in the United States, where they became known as eurogames, flooding the market and opening the minds of American designers, who were brainstorming a different kind of games, more influenced by role-playing and wargaming traditions: titles like Cosmic Encounter (1977) —according to Richard Garfield, a major inspiration for Magic— and Arkham Horror (1987) —which now survives in a third edition and in a collectible card format— didn’t shy away from luck but spiced it up with combat mechanics and asymmetrical powers, where each player could do things so radically different that they broke the basic rules (hence the golden rule of Magic: “if the cards contradict the rules, follow the cards”).

So what defines a modern game? It’s hard to settle that debate because we’re not talking about an organized movement. There is a clear quest to reach new audiences, expand the repertoire of mechanics, eliminate or reduce some negative aspects like player elimination or excessive game duration (remember that time you got stuck in Alaska in TEG and had to endure your friends’ entire war while you did nothing?), as well as a recognition of the author’s figure, which began to be named on the covers.

The truly mind-blowing thing about this renaissance of board games is the epiphany that anything can be a game. In the classics, themes often revolve around war —TEG, chess, naval battle—or have no narrative behind them at all —truco or generala. What about a game about escaping from the office? Or about having consensual sex with an alien? Or a game about designing board games? It’s not just about the themes, but also about the mechanics. At that initiatory gathering at Exactas, I sat down to play a game that seemed to have 100 different pieces. It was called Tzolk'in and it was about being a Mayan chief and doing Mayan things, like praying to bloodthirsty gods and gathering corn. The crazy part is that there’s a giant Mayan calendar on the board, a gear that looks like it came out of a steampunk world, and when you turn it, you rotate other interconnected gears, modifying your actions turn by turn. Pure madness. I lost like in a war, but that night, on the bus 107 at six in the morning, I saw the matrix.

I couldn’t stop thinking about games. I got home, turned on my computer, opened Word, and started throwing out ideas until I fell asleep. The next day, I took advantage of the fact that my office bosses were on vacation to keep adding flashes. By the afternoon, I had over 50 board game concepts, from surviving zombies to guessing the secret name of an Egyptian priest. I talked to my friend, who was just as excited, we chose the one we liked the most, and started co-designing it.

An Event to Bring Them All

Six months later, our first little game hadn’t prospered. It was a masquerade of monsters, and maybe spending several nights inventing the powers of all the characters instead of thinking about the basic rules didn’t help much. But we were still having fun with the idea and couldn’t stop trying things. Sometimes we tested a bit with other friends we also played with, but none of that group had the design bug. So we thought we were alone in this, or so we believed.

In April of that 2018, we found an ad online for an event happening at the Centro Cultural San Martín: the fourth edition of something called Geek Out Fest. We had no idea what it was about, but we went for it. And it was epic. The entire floor and basement of San Martín packed with nerds, banners for Warhammer and Magic, and booths selling games brought in from abroad. People in cosplay. Tables and tables filled with colorful boxes and a swarm of cool folks ready to teach you how to play them. Suddenly, the thing that had been obsessing me for half a year turned into a collective frenzy.

The board game scene finds its peak celebration at these events. For many years, there were two main ones: Geek Out Fest, organized by the Geek Out community, and the National Board Game Meeting (or ENJM), initiated by the folks at La Cantera. The main difference is that Geek Out Fest was organized privately and always took place in CABA, while the ENJM defends a federal character, changing its venues year by year —the 2025 edition was in San Luis and this year will be in Neuquén— based on proposals submitted from different provinces and an assembly vote, where potentially anyone can participate.

Aside from that, both events function very similarly: there are tons of games, tables, and chairs to play, but also talks, stands from publishers, and businesses selling accessories, from custom dice and playmats to handcrafted tables. These events have a very community-oriented and accessible character: they are completely free and are supported by donations, sponsors, and a lot of volunteer work. There’s often support from local municipalities (managed by local gamers), who offer cheap state accommodations to attendees from all over the country, and some days even invite kids as a school field trip.

This is very distinctive of Argentina. In other countries, equivalent events —like Gen Con in the United States or Essen Spiel in Germany— are organized by companies and charge for entry, turning into primarily commercial experiences and also niche (though that niche is colossal compared to ours). Much accessibility is sacrificed in favor of gaining spectacle and attracting the market's whales: the big board game spenders willing to pay between $500 and $1,000 that you can blow on entry, travel, hotel nights, and everything you consume at the event.

The last Geek Out Fest took place in 2019, but post-pandemic, the number of events has exploded instead of dwindling. Nowadays, the gamer calendar involves a game of Tetris with travel, as no one wants to miss Cultura en Juego in Rosario, La Plata Lúdica in Buenos Aires Province, or the Regional Board Game Meeting Conurbano Sur, to name a few, in addition to the always iconic ENJM. On top of that, a new line of smaller gatherings is emerging, organized by individuals, clubs, and board game cafés. An example from CABA is Prototipazo and the testing days at Punto de Partida and Doda. If events like the ENJM are the procession for the devotees who already know them and have them marked on their calendars, these spaces do the daily wololo, attracting and converting families, groups of friends, and passersby who join in, always thanks to a gamer willing to teach them any cube-moving game.

That Geek Out in 2018 was a turning point in my life, but the most iconic moment happened when I met some designers who came to showcase their prototypes and invited me to try them out. It doesn’t make sense to talk about my representation in a field so dominated by white men, but at that moment I felt like a kid seeing a superhero on TV who looked like him. I finally found more crazies like me. That afternoon, my friend and I sat down to play Who Wants to Be President?, a political game where you were a governor trying to reach the Casa Rosada, for which you had to gain the support of various sectors —deliciously caricatured— and juggle a petty cash fund to keep the other governors (your competition) in check until the final round. What initially seemed like a re-themed Monopoly (it even had paper money) turned out to be a sharp and very fun political satire. We battled with DNUs, union strikes, and bribes, had a blast, and when the game ended, its creators asked for our feedback to see what needed to be changed before publishing it.

A complicated market

Who wants to be president? was designed by Nicolás Martínez Sáez and developed by Omar Dambolena. Nicolás started it in 2014 when, in his own words, he “didn’t have much idea about the world of board games” (just like my friend and I). The design process took him six years, and he finally self-published it in 2020. That same year, he won the Poncho award (thanks to the feedback we gave them, for sure) for Best Adult Game and was a finalist in the Alfonso X awards, the two highest honors in the local scene, which are now merged into the Argentinian Ludic Awards. The game went on a national tour and even made its way to Spain, reaching well-known YouTube channels in the scene like Análisis Parálisis. However, it took Nicolás three years to sell the modest 250 units he had produced in that first edition, and based on that commercial difficulty, he decided to release the files in Print & Play format so anyone can try it for free.

Who wants to be president? is an archetypal case in the design scene in Argentina, in many ways. First, there's self-publishing: a group of friends or family who love board games decide to invent one, produce it, and sell it. This is the origin story of the vast majority of Argentinian publishers, even the heavyweights today like Yetem (creators of TEG), Buró, Maldón, or The Blue Dragon (Ruibal is an exception; it started as a leather goods shop dedicated to making dice cups). A second step for many publishers is to license games that have already been successfully published in other countries (as is the case with Maldón and Azul or Ticket to Ride). Publishing local designers is almost always a third step that happens much later in a publisher's life, which makes it challenging for many authors who want to focus solely on inventing games and have someone else publish them.

Secondly, the local market consumes little national design for often contradictory reasons. The general public usually doesn't buy games from here simply because they don't recognize them or because they won't buy games that are too different from what they already know (nothing sells like TEG or Estanciero, even if they aren't very original). And Argentinian gamers, who do have access to information and are willing to spend, often prefer to import games costing over 100 dollars rather than buy national titles that, with a good dose of cipayismo, they consider inferior or simply uninteresting. Fortunately, this trend is reversing thanks to the spread and growth of local offerings, but it also faces a slowdown due to the recent easing of import restrictions and the influx of foreign games.

And thirdly, what the case of Who wants to be president? teaches us is about limited industrial capabilities. Besides the fact that, due to the previous point, no one would want to risk making a game that is too expensive in materials, many technologies are simply not available in Argentina. We're not talking about crazy things like injected plastic miniatures: until recently, it wasn't possible to make a box of the same quality as any international game. This lack is also changing, thanks to local players investing in infrastructure, but also because it has become much more viable to do what is done worldwide: outsource production to China. This crossroads between developing local industry and dependence on the Asian giant is a debate we share with industry titans like the United States and Europe, who until a few years ago practically produced no games locally. Indeed, the tariff war under Trump caused a massive upheaval in the American board game industry, as it violently and overnight increased production costs, with no possibility of replacing it nationally (again, we're not talking about microchips, but about components as simple as custom wooden pieces).

The Argentinian hustle

Industrial limitations and the need to create an accessible product have greatly influenced Argentinian design, almost to the point of becoming a distinctive feature of our games. Without inventing them, here we popularized and refined very distinctive game formats like wallet games, made up of only 18 cards (a number that can even be printed on the leftover material from larger games). This format characterized, for several years, the publisher Pulga Escapista, which took it to its maximum potential with Rivales, a fighting game featuring anthropomorphic animals inspired by historical and legendary figures. Rivales is published in different volumes (there are already three), and each comes in a wallet with two characters that can face off against those from any other volume, creating a roster that will only continue to grow and gives this small game a feel of a grand experience. To accompany that ambition, this year a competitive league season is launching with venues in different provinces where, of course, players can battle with any of the six characters.

Another innovative format is the one card, games that, as the name suggests, consist of just one card. If it sounds difficult to design a game with that limitation, imagine trying to make it economically viable. In fact, many one card games are given away as promos for larger games or as a calling card for a publisher or author. But there is one publisher that has managed to find a way around this.

Supernoob Games started similarly to Who wants to be president?: two friends (Julián Tunni and Aibel Nassif), inspired by Warcraft III, wanted to create a similar board game. Thus, Arte de Batalla was born, a title of very artisanal production that is now extinct. After that initial learning step, they shifted towards minimalism mixed with a lot of product design, humor, and a dose of kamikaze: their second game was a solo game, something that, while it existed and had its audience in other countries, was unthinkable here. Lunes surprised everyone by generating a frenzy, perhaps thanks to its charming theme of escaping from a boring office, and allowed Julián and Aibel to continue their editorial project. Today, Supernoob remains at the forefront of local design with innovations like Ofuda Slap, a game made of magnets for the fridge.

Their most recent success is One Card Cereal Killer, a fantastic deductive logic game where we pursue a killer who leaves cereals as clues. One Card Cereal Killer was sold in a wallet with very cute components (the best part: the rules are presented as a newspaper from a noir detective story). Not only was it a commercial success, but it also caught the attention of Spanish publishers and was licensed to Primigenio Games; meaning they get paid to produce and sell an Argentinian title abroad. With this agreement, Supernoob was able to design a new edition of the game, in a small box format, with more content and better quality components. It’s a compelling case where a game formatted to suit our conditions succeeds abroad, positively impacting the local scene.

One Card Cereal Killer is not the only game licensed abroad. The first was Mutant Crops, designed by Sebastián Koziner, published by Dragón Azul, and released in the United States by Atheris Games. Other titles have crossed even more distant borders: The Secret Valley, by Martín Oddino (self-published under his now-defunct editorial RunDOS studio, which also developed video games and recently re-released by Neptuno Games), has been released in countries like China and Russia and has the honor of being the highest-ranked Argentinian game on Boardgamegeek.com (or as it’s known in the community, the BGG), which is like a mix of Wikipedia, IMDB, and a mega forum for board games, a true relic of a better Internet. Oddino is one of the local designers with the most international success (he has two games published abroad and another five set to debut in the coming years). His beginnings are identical to those already mentioned: he self-published his first title, Magus: Fortuna et nostis, the first Argentinian dungeon crawler, and re-released it in an improved second edition two years later, after founding RunDOS Studio. There are rumors that we will soon see a third version of the game, this time abroad.

Inflation bubble or geopolitical reordering?

Some voices say that the renaissance of board games we are experiencing is a bubble, soon to burst. The causes would be a dangerous combination of market saturation (especially from Kickstarter games with lots of miniatures and little testing) and rising prices (the logistical crisis from the pandemic and the recent tariff war between the United States and China caused inflation that has yet to recede), in a market where demand does not keep pace. Others point to the gradual monopolization of the industry by giants like Asmodee and Hasbro, while publishers that used to be creative vanguards now only bet on safe bets, like the current Fantasy Flight Games that only milks its sacred cows: Star Wars, Lovecraft, and Marvel.

Whether these prophecies are true or not remains to be seen. The most likely scenario is that a shift in hegemony is brewing, coupled with what is happening in the rest of global geopolitics. In these seismic movements, Latin America, and especially Argentina, is repositioning itself as a promising player. While it’s unlikely that our market and industry will make an explosive leap, the talent pool is undeniable: five of the 25 best-ranked Latin American games on BGG are made here, with only Mexico matching us in contribution, a country with three times the population and a much closer trade relationship with the main cardboard market, the United States.

This assertion does not (only) suffer from Argentinian exceptionalism. Many publishers are starting to look to our country for novel titles. Besides his career as a designer, Oddino has been representing Meeple on Board (M.O.B.), a Greek agency that manages board game licenses, in Argentina for a few years now. Through this designation, M.O.B. is firmly establishing itself in Argentina to find published games and prototypes that could succeed abroad. This has concretely translated into many national titles circulating at major fairs around the world, like Essen Spiel. It has also impacted the local scene: during 2025, M.O.B. organized a series of prototype contests at the most important events in the industry, seeking to recruit promising designs. Thanks to one of those contests, for example, I was able to send a prototype of mine to a Japanese publisher that is considering it for publication, something that not only blows my mind but would have been an impossible bridge to cross a decade ago.

But none of this would happen without a prior structure, much more nourished from the ground up. In 2023, five years after attending that Geek Out, I was still isolated from the local scene. I had had some very privileged experiences, like winning a scholarship to attend the Tabletop Network convention in the United States and meeting some big names in the industry, like Geoffrey Engelstein and Eric Lang. And yet, I still hardly knew any Argentinian designers.

On January 5, 2023, I decided to join the guild (yes, BGG has guilds, like WoW) of Design in Argentina (which had more cobwebs than active users) and throw out a post to form a stable testing group, something I was starting to need to improve my designs. Then, like in the best side quests, a stranger approached me (digitally) and invited me to join a rather shady secret society (a massive Telegram group that at that time had about 50 users). This society was the community of Board Game Designers, or DJM, and it became my refuge. This space now has over 300 designers, publishers, illustrators, and other folks. Every day, information about contests is shared, Byzantine debates are held, and virtual and in-person tests are organized. You can ask the most basic question and get a response from one of the top designers or publishers in our country. This community know-how and solidarity is the ultimate platform for raising the bar in design, allowing us all to rise together.

So, young designer, I now invite you to join DJM or, if you’re not that interested in designing but want to stay updated on games in Argentina, to the Ludic Community. And if you want to start designing, here are some tips:

- Prototype your idea, test it alone, make changes, then test it with others, make more changes, and repeat this loop until you have something resembling what you imagined (but above all, something fun).

- Join a community. Now that you’ve joined DJM, get involved in a local event or test other games. Not just for camaraderie; you’ll learn a ton.

- Try new games all the time. Especially try games you think you won’t like. You might be surprised. And even if you still don’t like them, understand what they do well and why others enjoy them (just like the games you love have their flaws). And steal, steal with both hands. Below, I’ve left you some recommendations for all national games so you can have fun and get inspired:

If you like:

- TEG, try Pasaron Cosas

- Catan, try Cultivos Mutantes

- Carrera de Mentes, try El Erudito

- Generala, try Jardín Japonés

- The Mind, try Fungonia

- Street Fighter, try Rivales

- Pictionary or Dixit, try Pintó

- Tetris, try Juanito Blockits

- SimCity, try Utópolis

- Jenga, try Cleptómano

- steampunk, try Amenaza Gigante

- Dobbles or Jungle Speed, try El Camarero

And if you like buying games, I highly recommend the wonderful Argentinian search engine, www.cazagangas.com.ar