My generation, the one that was born in the late nineties and early two-thousands, was perhaps the last to experience the more artisanal phenomena of the internet: forums, flash games, Facebook pages, cybercafés, pirated downloads and modded PlayStations 2. An internet where not everything was mediated and standardized, at a time when big tech and Silicon Valley, even social networks, were strange names that didn’t mean much to the average person. An internet that was still a place, because your desktop computer or the cybercafé were the only possible access points. As if that chipped proto-melamine desk with a sliding tray for the old keyboard, full of crumbs and without lights, was a portal to a parallel and almost infinite reality, and you could only enter from there. It didn’t chase you from your pocket or cover everything with a decadent halo. The world before selfies.

Are they Argentine things or things about Argentina?

Here in Argentina, the era of the internet meant a sort of normalization of trends: fashions generally arrive later to peripheral countries, which are always in a kind of macabre race to see which adapts first to what the first world imposes. There are many fields where, although the reception of a foreign phenomenon doesn’t fully explain it, it is at least strictly necessary to understand it: music, some say, never managed to break that pattern of reception. It is also said that national literature stopped following foreign trends after Borges and Bioy and the Latin American boom. In philosophy, a few mention the work of Luis Juan Guerrero, the first doctor in the field in the country, as a missed opportunity for national philosophical emancipation: his Estética operatoria en sus tres direcciones proposes a native but universal system of thought that, unfortunately, was forgotten by tradition and academia, amidst coups and European fashions. Silvia Schwarzböck uses it as an example in Los espantos to talk about Argentine philosophy that doesn’t focus on Argentina, but can only be mentioned as an exception. Both she and Guerrero pick up the line of debate that Borges brought in The Argentine Writer and Tradition, a text he first published in an issue of the magazine Sur in 1955. The central distinction Borges makes there is between, let’s say, Argentine things and things about Argentina, and their relationship with universal culture. He wonders whether we should try to distinguish and follow something like a guide to be more Argentine, more criollo, or if we should settle for the evidence that we will always be so and create freely. The sentence urges you to get to work:

That’s why I repeat that we shouldn’t fear and that we should think our heritage is the universe; to try out all themes, and we can’t limit ourselves to the Argentine to be Argentine: because either being Argentine is a fatality and in that case we will be anyway, or being Argentine is merely an affectation, a mask.

I believe that if we surrender to that voluntary dream called artistic creation, we will be Argentine and we will also be good or tolerable writers.

The thing is, recently some friends told me they started playing Argentum Online again after years, just when I had been thinking a lot about traditions of Argentine things. Is it enough for something to be done for years in Argentina for it to be an Argentine tradition? How many traditions can we name without falling into chauvinism? Does it mean talking about mate and gauchos and Corrientes and Esmeralda, or do other topics count? Can you create an online medieval fantasy game that is truly Argentine? Does Argentinidad depend on originality, on the lack of foreign references, on its productive fagocitación, on vernacular influence? On what fields can Argentines legitimately claim the right to universality? In how many cultural fields do we eternally chase an imaginary carrot?

Well, with the internet, our tendency to reception seemed to have a big, bright exit door. Argentina started by fighting the most powerful empire in the world with a couple of pots filled with hot oil and a Salteño with a totally altered perception of reality who took a boat on horseback: imagine what that same people could do with unlimited access to all universal knowledge and a virtually unrestricted and deregulated network of connectivity. The speed at which trends circulated made us think we would never again suffer a lag with the culture of the powers. There was no need to worry about arriving late anywhere: on the internet, we were part of the world concert. Thus, in the two-thousands, it seemed like anything could be done: did you want to have an infinite library of video games available on the most advanced console to date? You modded the PlayStation. Did you want to listen to all the music in the world on your mp3 without spending a dime on CDs? You went to Ares or a forum. Movies? Megaupload. Did you want to create one of the first successful MMORPGs in the entire world? You built Argentum Online, dude, it wasn’t that hard.

Argentum Online: a coke in the desert

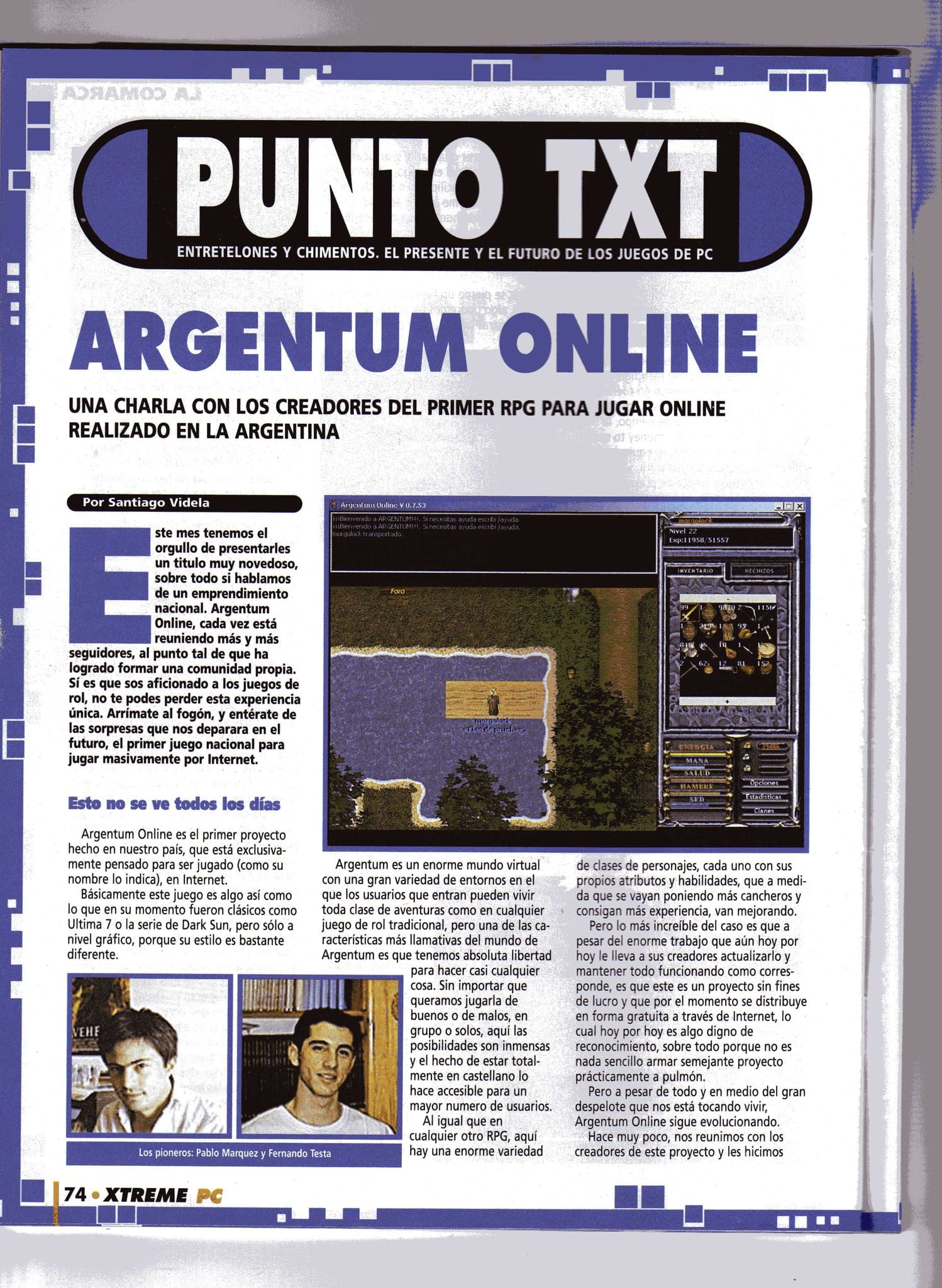

In 1999, Pablo Márquez (better known in the community as Morgolock) left his Anthropology studies at the National University of La Plata to dive into Systems. In the meantime, he started to explore, out of curiosity, how he could develop a free and massive online role-playing game using Visual Basic. There were only a few, all in English and paid, and the idea of accessing these technologies was very attractive to several young people here. Pablo began recruiting collaborators in various forums, and within a few months, after several tests, he had the first prototype running with a specialized forum supporting it. People dedicated to making music, maps, character skins, animations: everything. Every now and then, they would gather at Pablo’s place in La Plata for intensive work sessions.

By 2001, the game already had a huge number of users, and the servers could barely keep up. Javier Otaegui, founder of the developer Sabarasa (and creator of, for example, Malvinas 2032, a strategy game that involves killing Englishmen and reclaiming the islands), offered Pablo help to improve his connectivity. He then moved to the Juegos Online platform, which provided servers for various video games in Argentina.

The game continued to receive more and more traffic, at a time when MMORPGs (massively multiplayer online role-playing games) were just taking their first steps and, as I said, only had paid servers in English. After a couple of articles in well-known newspapers and after Pergolini mentioned them on the radio, Argentum was a total success. The group was formally a team: they called themselves Noland, according to Márquez, because, since everyone worked from home, it was a group without land. Meetings with major companies, advertising in mass media, thousands of daily users, and international reach. A serious thing.

Fast forward a quarter of a century and the game still has a solid player base, regular updates, and a very strong community. Why?

The gameplay was and is super simple: you create your character, choose a class, a race, and some initial stats, and you head out into a world full of fantasy cities, different landscapes, and dungeons. There are two factions to join, although you can also be a renegade, and all groups have their cities. These serve as safe zones where you can chat and trade, and there are also neutral ones. Many people use these spaces as forums, and the chats are often filled with ads about items in and out of the game (from high-level accounts, special weapons, or hard drugs) and users who just want to chat. The economy relies on player trading, and everything is sold. There are Game Masters with special powers who act as moderators: they are characters known throughout the community. It has a robbery mechanic, and scams and tricks are common currency. There are minimal quests, like “kill ten wolves and five spiders,” and everyone’s favorite activity is going out to shake, the millennial term for PvP combat.

Combat is quite frantic and has a magic and potion system. You go out to level up by killing wolves, spiders, and NPCs in unsafe areas and dungeons, where you can encounter other users to ally with or become enemies. When you level up, you have to carefully choose which skills to assign your experience points, because they are few and very important. The items have a complicated aspect: if you die, you lose everything and have to walk like a ghost to a city for a priest to resurrect you. This is the game’s harshest dynamic, and what makes it as competitive as it is addictive. If you’re only into PvP, there are arenas for that too.

Others choose to be workers instead of fighters: trading and crafting key items like weapons and armor, chopping wood, mining, and fishing. You can also form clans with friends and strangers, which have their own internal hierarchies and are important because the game relies heavily on the social dynamics that emerge. If you do well, you can participate in clan tournaments.

With these few mechanics, the game quickly found a super fun and organic dynamic, with its own economy, reports of corruption, ethical codes, and parallel markets that operated with real money. It was a success because you could run it on a microwave (1GB of RAM) and the center of its gameplay was always the total freedom of the player, at a time when open world wasn’t as overdone as it is now and there was nothing like Minecraft. It was, as the genre rightly points out, a massive multiplayer role-playing game, and that’s why it served as a preamble for virtual relationships in the country, because it has a very strong focus on the activity that articulates the entire internet: role-playing using an alternative identity. But that’s not all that can be said about the key to its success.

Freeing the code, freeing the soul

So far, it’s a nice, colorful story about a game developed in a peripheral country during a crisis that manages to become famous in the tiny Argentine internet community of the time. It doesn’t resolve any of my grandiloquent and philological questions, nor does it explain why it continues to function twenty-five years later. Well, according to Pablo, the project received many financial offers: they rejected practically all of them. No one ever saw a peso split in half. The game was made for the love of art, and any possibility of cutting the creative freedom of its developers meant killing the project. But after years of hard work ad honorem, and some clashes and controversies with other collaborators, Pablo wanted to find a way to step back from the project without killing it or commercializing it, to protect the community.

The game was super popular in Argentina but also in Spain, and some Spanish players asked about the possibility of getting the server executables to open one there. Pablo agreed because, as he says, the whole project was possible thanks to the openness it always had to welcome new collaborators and provide opportunities. Later, wanting to graduate and tackle new jobs, the solution seemed logical: to free the source code and let anyone who wanted modify it to create their own version. Similar to what id Software had done a few years earlier with Doom and Quake, making it possible for the former to run on this very portal. Thus, eliminating almost all possibility of the game having profit motives and literally handing it over to everyone, Morgolock hung up his keys to continue working as a developer on other projects.

What was the result of the openness? FénixAO, ImperiumAO, Tierras del SurAO, Tierras PerdidasAO, Mundos PerdidosAO, BenderAO, FuriusAO (also available for Android) and many other versions that managed to have even more players than the original and add all the changes they wanted to the game. Keeping “AO” in the name was an almost folkloric convention, allowing you to insert yourself into the world of the original while paying homage to it. For the Argentine internet community, the impact was incalculable. I remember being ten years old and excitedly watching a little friend who had downloaded all the textures to learn how to program video games, as if he had been given the formula for Coca-Cola. It was, for many, the gateway to coding language, but also to online games in general.

The journey of Argentum left behind a tremendous amount of anecdotes that shaped the digital ecosystem of its time, and in the process, several of its servers died, were resurrected, and died again. Márquez created an immortal, unpiratable game, as alive as the people eager to play and work on it. It’s no longer a work created by an author, but a code released for anyone who wants to interact with it. It resembles a lot more like a meme than a building or a movie, which are the most common artistic parallels used to discuss the production and reproduction of video games. As a place, AO is an old town with a loyal community, welcoming occasional tourists and resisting becoming a ruin. Its communal and independent logic speaks volumes about how Argentinians learned to navigate cyberspace.

Today, Argentum has experienced a huge revival since the pandemic and continues to break user records twenty-five years after its launch. Playing it is still a blast, and you can even run it on a toaster. It’s available for free, as always, here. The most historically successful server, as well as the most modernized version of the game, is ImperiumAO (IAO), which closed and reopened as Imperium Classic and can be downloaded here. If you’ve never tried it and are in the mood for something new, I highly recommend giving it a shot, whether solo or with friends. It’s a huge testament that video games never needed top-notch graphics and complicated technology to be excellent.

Model to build

This is one of many Argentine experiences that teetered on the edge of total success. Like all stories that seem unfinished, it leaves a ton of questions: Is it necessary not to sell out for a project to maintain its authenticity? Are there projects that, by their very nature, are non-commercializable? To what extent can the under be operational? Can genuinely good things be created if they don’t provide for their creators? Is it necessary to aim for mass appeal and free access for something to be popular? Did the internet finally allow us to catch up to a global phenomenon? In what other fields do we have the opportunity to be, today, at the forefront? How much did Argentum influence the Argentine video game industry? What is its future? Can we already call it an Argentine video game tradition? And what about the internet? How long can our culture, fed by cultural scavengers and a couple of juicy legacies, hold on?

Argentum, by releasing its code for everyone to use for free, has established a legacy. But it doesn’t leave behind just code or a couple of initials to tag onto your title; it leaves behind a responsibility: a duty and a power. We are in the land of everything yet to be done. We are called to think big because we can create many good things. AO is a game made by and for its users: the same should happen with culture. The ideal world that rises from our soil, its heroes, myths, and works, should be for us and by us. Today, particularly, we desperately need to become aware of our capacity for action. There are plenty of examples. What’s missing, besides money, is people dedicated to creating genuinely good things, whether at the expense of starving or sacrificing all their free time. Would you like something new and awesome to happen that could change all our lives? A movie, an album, a cultural center, a magazine, a game, a club, a program, a party? Search online, gather a few friends, and make it happen, buddy. It’s not that hard.

EN

EN