At the end of the last millennium, Babasonicos released Miami, one of the most exceptional albums of their career. But Sony wasn't giving them support commensurate with the buzz they generated, their international touring, local demand, or their absolute uniqueness. Like so many other times, the group took advantage of the confusion to rebrand themselves as a "band without a contract", a narrative that injected a survival instinct amid the departure of their manager Cosme and their DJ Peggyn, the collapse of the major-label deal, and the direction the country itself was heading. It was a key stage for the band to reach the legendary stature they'll be revalidating again at year's end, with two concerts at Ferro, December 6 and 7.

From that work ethos –and before partnering with PopArt in the Jessico era– they made a DIY decision that keyboardist Diego Tuñón ranks among the best in their career: grab those preserved, set-aside songs they'd made but not used on their '90s albums, turn them into B-side CDs, and sell them at shows. That way they not only maximized profit by cutting out middlemen; they also gave fans a steady stream of physical keepsakes –souvenir discs packed with outtakes and rarities.

As the band tells it in Roque Casciero's book Arrogante rock. Conversaciones con Babasonicos, these releases were quasi-bootlegs of a sort –manufactured and distributed by the band itself through its Bultaco imprint– and they brought in the first real money of their career. It was about ten thousand dollars, which they used to build, in Tortuguitas at Adrián Dárgelos's house, the studio where they would record Jessico, the best Argentine album of 2001 and of the 2000s –and, for me, the best of the millennium.

Drummer Panza Castellano shouldered those editions. He compiled the tracks, handled the artwork, sent them to be pressed and distributed them to record stores –another point of sale that complemented the shows. The standard was fairly rustic: artisanal, immediate discs, both in their physical make and in their content, with little rework on the recordings, almost no post-production, and minimal frills on the cover art (save for the bluish sequin tucked into Vedette's jewel case).

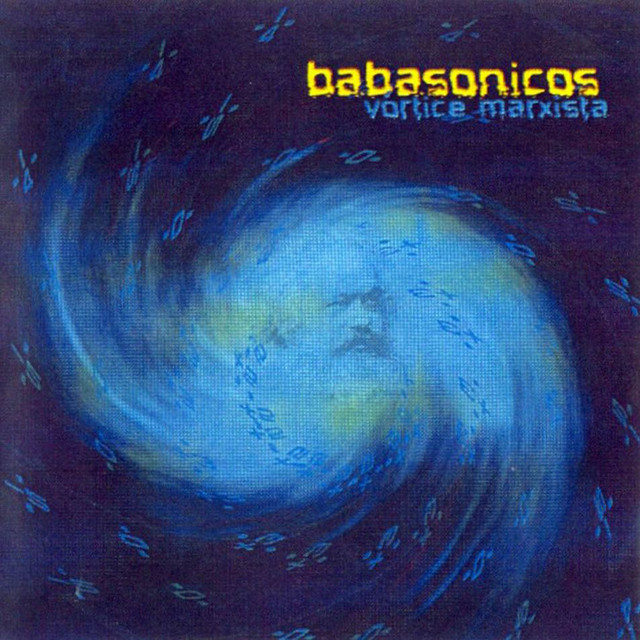

Vórtice marxista, with that sky-blue spiral and Karl Marx's diffused face at its center, gathered tracks discarded from Pasto, Trance Zomba and Dopadromo –their first three albums, from 1992, 1994 and 1996, respectively. It's the Babasónicos of heavy psychedelia, hardcore-rap turns, pop humor –teen, televisual, suburban– and a darkness stretched tight against the youthful epics of extreme sports, entheogenic experimentation, and making a ruckus with friends.

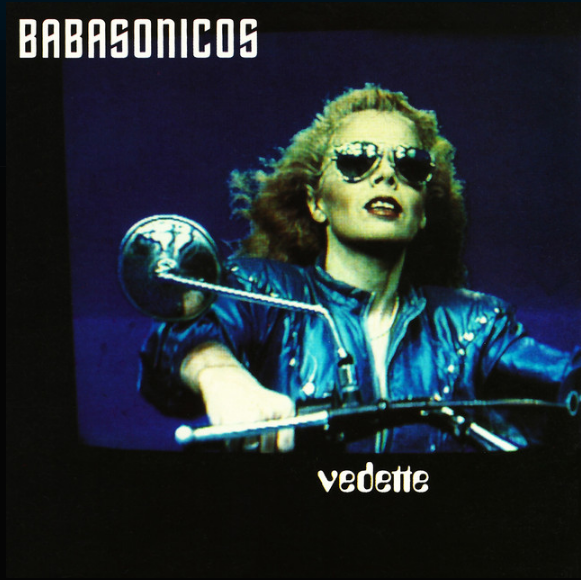

Vedette, with that goggled, motorized blonde on the cover, brought in what they didn't end up using from the Babasónica sessions. A gallery of songs perhaps too "glam" or luminous compared with the more belligerent, obscurantist tone of the official album: on Babasónica, everything was really bad, man.

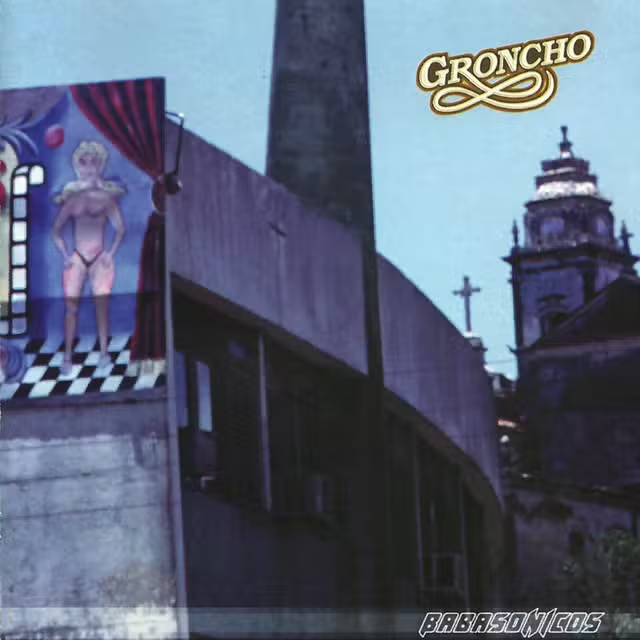

And Groncho, with its urban image of cornices, marquees and domes, arrived with tracks dangling from the making of Miami. The same parade of characters and situations from the end of first-world Argentina in the '90s, but treated more loosely –in parallel songs that set up a lab of atmospheres and voices looking toward the band's immediate future.

Vórtice Marxista

The first to circulate was Vórtice marxista: an initial eight-track edition in 1998, then a reissue expanded to eleven tracks in 2000, when the other two came out. It compiles songs from the band's first five years that were left off the first three albums. As a whole it keeps a dark, psychedelic, heavy tone; track by track, though, you hear intentions that jar with their parent albums –or a subpar take. Songs a bit out of focus, blurred, gummy-eyed, with scratchy throats and lukewarm muscles.

It opens with "Larga siesta", "Fioritos" and "Antonio Fargas", three tracks built on a similar design, each with a psychedelic "break" just past the halfway mark. A primitive Babasonicos formula interrupted by "La muerte es mujer", an almost devotional piece written by one of my favorite tandems in the group's 33-year run: Tuñón/Dárgelos.

There's also a lot of reveling in the geography and genealogy of the rough-and-ready Conurbano of the '90s, with neighborhoods turned into platforms for civic delirium: Chingolo reimagined as a mythical hill ("Chingolo Zenith") or the epic of the "Fioritos". And there's an undeniable pull toward film and TV luminaries –specifically the side characters and the slightly declassed. "Antonio Fargas" is Huggy Bear from Starsky & Hutch, for instance; and "Los clonos de J.T." winks at John Travolta and Saturday Night Fever.

Round that out with nods to weed, wah-wah pedals, small-percussion textures like bongos and maracas, hardcore of the calm/fury/calm/fury school ("Forajidos de siempre"), and a finale of four very particular tracks. The closer on the original pressing, "Cerebros en su tinta", is ten minutes of deformed Babasonicos reverie. The reissue adds "Traicionero", a highly cinematic instrumental from the Dopadromo era composed by Peggyn; "Fórmica", also circa Dopadromo, signed by Tuñón with a marked drum-and-bass spirit; and "Bananeado", from the Trance Zomba days, a chicano-meets-alt cut –Illya Kuryaki and the Valderramas vibes with a Capusotto streak– devoted to vegetal psychedelias.

Vedette

Vedette came out in 2000 but gathers tracks recorded in 1996–1997: outtakes from Babasónica that, residually, still carried over Dopadromo's approach. Both albums had staged Good-vs-Evil and light-vs-darkness scenarios that Dárgelos would keep revisiting across three decades of Babasonicos. If Vórtice marxista recycled the early years' thick psychedelia, Vedette offers a more melodic, glam counterpoint to that vibe. There are acoustic guitars and more affective lyrics, but always with the Babasonicos twist: kinked phrasing, fashion references, social satire, suburbia and delirium.

The CD starts quietly with "Dopamina", a track that may not be essential yet drops lovely lines. Then "Muchacha magnética" joins that ongoing saga of rockers the band keeps trying out on each album. "Su auto dejó de funcionar" goes for what's close-to-home, almost unplugged. "La hiedra crece" unfolds slowly; "Italia 2000" is a light instrumental; "Vórtice" is an intense rocker; and "YSL" gives us a cinematic sound frame for a coquettish secret agent.

"Sé que los malos viven más y la pasan mejor que el común del hombre" sings Dárgelos on "Bandido", one of my favorites here. I also like tying "Chupa gas" to French Decadentism, and I will never not enjoy the title and categorical punch of "Careta de Acassuso". As always –here, there, and on every record– more weed references. Near the end, "La salamandra" and "Arenas movedizas" share a weakness: their own meandering nature keeps them from deciding what sort of song they want to be.

Which makes perfect sense if we remember these are, for all the beauty in some cuts, discard albums –offshoots of the central works that gave meaning, identity and temper to Babasónicos' first phase: a spectacular pentagon running from Pasto ('92) to Trance Zomba ('94), Dopadromo ('96), Babasónica ('97), and Miami ('99).

Groncho

Groncho had the shortest path: songs written and recorded in 1999, left off Miami, and retrieved in mid-2000. It landed just after the Sony contract ended, with the band unsigned and the Argentine economic and financial crisis building toward the events of December 2001.

The sound on Groncho –and the songs' more atmospheric bent–feels tighter and more defined, helped by trimming the tracklist to just nine (versus eleven and twelve on the previous B-side sets). There's also a clearer group identity, reinforced by artwork that sharpened the contrast: if Miami is, by definition, beaches and shopping malls, then the Groncho counterimage is damp concrete structures, window frames streaked with rust, shoddy doodles on rickety billboards, churches omnipresent in the social subtext.

Songs like "Pop Silvia" or "Clase gata" make light statements about the social cult of the "rich and famous", heavily buttressed by mass media. Where other records (official or parallel) sometimes find an epic of the underbelly, the Miami + Groncho dyad traces the dynamics of a decadence unfolding right under the spotlights. To step into that vibe, this last '90s B-side opens with a tandem that proposes a necessary blackout in the face of the millennium's urgency ("Pon tu mente en blanco" in "Demasiado"; "Nervios off" in "La pincheta").

"El súbito" is another of my favorite tracks from that Babasonicos era, without drawing lines between official and unofficial. "Dame más memoria para recordar la libertad cuando no la tengo", Adrián pleads –and also: "No me hieras a mí porque te hieres; ayuda". Next comes one of the most endearing cuts, "Promotora"; then "Pavadas", with a Madchester sway; and right there "Pop Silvia", a minimal tune sung by guitarist Mariano Roger. Once again the closer is instrumental: "Boogie boutique", almost an homage to film soundtracks.