There is an imaginary line that runs through the entire 20th century, crosses the threshold of the 21st, and reaches our own day without losing any of its force. A line that connects the Futurist avant-garde of the early 1900s with the last aftershocks of New Wave science fiction in the late '60s, cyberpunk cinema, the body horror of the '80s and '90s, and the weird Latin American fiction of the new millennium –an ongoing process of appropriation and relay-style reinvention. A line –like the white stripes painted on road asphalt– that guides us toward fictional universes where the automobile is a deity, flesh fuses with metal, and speed is the only religion.

Futurism, the Avant-Garde That Loved Speed

Speed is one of the most important traits that distinguishes contemporary civilization. In 1909, the French newspaper Le Figaro published the Futurist Manifesto, a declaration of intent written by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti that laid out the foundations of Futurism: an Italian artistic avant-garde, anti-historical and anti-naturalist, that sought to break the hegemony of tradition and rebel against the harmony of classical art to make room for new forms of expression. A new art whose aesthetic ideals glorified movement, war, technique, and machines –and that, above all, worshiped speed, the deity of modern times and the metropolis: "We have no hesitation in declaring that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed (…) A racing car, which seems to run on shrapnel, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace."

Futurist artists –painters, architects, poets, playwrights, photographers, musicians– exalted aggressiveness, professed a love of danger and a devotion to violence, and glorified war, militarism, and patriotism. So it was not surprising that when World War I broke out, some Futurists put their bodies on the line for their country and their ideals: the poet Filippo Marinetti, the architect Antonio Sant'Elia, the painter and musician Luigi Russolo, and the sculptor Umberto Boccioni, among others, voluntarily enlisted in the Lombardy Volunteer Cyclists and Motorists Battalion in July 1915 to fight. Antonio Sant'Elia was killed in battle and Luigi Russolo was seriously wounded. Umberto Boccioni would die a year later after falling from his horse, and Marinetti would survive to fight again –taking part in the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 under Mussolini, and the siege of Stalingrad in 1942 as part of the Italian expeditionary forces, where he was wounded.

Nor were Futurism's sympathies for the nascent Fascist movement especially surprising. The Manifesto of the Italian Fasces of Combat, which Benito Mussolini read on March 23, 1919, was co-written by Marinetti and the syndicalist Alceste de Ambris. From that moment on, Marinetti began to be recognized as the official poet of the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento, and later as an intellectual reference point for the National Fascist Party.

Although December 2, 1944 –the day Marinetti died of a heart attack– is often treated as the formal death date of the Futurist movement, the truth is that for years Futurism had already ceased to be a novelty or a truly provocative avant-garde. While the first manifesto described academic spaces as "cemeteries of wasted efforts, calvaries of crucified dreams, registers of broken impulses", by 1929 Marinetti had not only become an intellectual of Benito Mussolini's regime but had also accepted a seat in the Reale Accademia d'Italia, betraying the ideals of the movement he himself had founded. Futurism would fade from the European cultural scene, leaving behind a mythology that later generations of artists would reclaim with force: speed as a way of connecting with the divine, and the automobile as a modern deity.

It is worth noting that Futurism chose –anticipatorily and riskily– to praise technique and deify the automobile in an unfavorable context. Before World War I, an average worker needed the equivalent of two years' wages to buy a car, and science fiction was pessimistic –or at least cautious– about the advances of technology and science. It was only in the mid-1930s, after the Great Depression and with Fordism consolidated as the dominant model of industrial production, that workers could access automobiles en masse. Around then, a hard, optimistic strain of science fiction also began to emerge –expanding the myth of science as a route to progress and casting scientists as heroes and protagonists of adventure stories– an era that would later be known as the Golden Age of science fiction.

After more than twenty years of hard science fiction's hegemony, in the mid-'60s an avant-garde literary movement arose within the genre itself that sought to "kill the father": the New Wave. Writers such as Michael Moorcock, Samuel R. Delany, Ursula K. Le Guin, Philip K. Dick, Harlan Ellison, Brian Aldiss, and J. G. Ballard –shaped by modernism and the counterculture, but above all bored by the mathematical chill and technical precision of the narratives that had dominated the Golden Age– began to bet on stories charged with social, political, and psychological themes. They brought in taboo subjects such as religion and drugs through riskier, more experimental narrative forms, giving far more importance to the complex interior space of the human being than to the conquest of outer space, gadgets, and technology.

It is during the ebb of this New Wave –and months before the 1973 oil crisis– that what may be the most controversial work by the British writer James Graham Ballard is published: a book that not only escapes the New Wave's boundaries but also, in a sense, closes it off –Crash, "the first pornographic novel based on technology", in Ballard's own words.

Crash: God Is an Automobile

Crash could be considered a spin-off of The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), an experimental, fragmented, and controversial novel. Chapter 12 analyzes the erotic content hidden in automobile collisions, presents the results of various studies related to the topic–such as attraction to cultural figures who died in car accidents (Jayne Mansfield, Albert Camus, James Dean), or the sexual behavior of collision witnesses– and describes experiments in which different groups of volunteers are asked to design the ideal automobile disaster. This chapter, titled "Crash!", ends with a grim conclusion: "It seems obvious that the car crash is regarded as a more fertile experience than a destructive one, a release of the libido of sex and the machine, reaching through the sexuality of the dead an erotic intensity otherwise impossible."

Ballard seems to suggest that there is an altered state of sexual consciousness –a G-point/space of ecstasy– that can only be reached through the union of technology, speed, and near-death experience. This jouissance, a pleasure so intense it becomes indistinguishable from pain, is the center of Crash's plot, which revolves around the disturbing relationships of people whose sexual behavior is driven by a paraphilia known as symphorophilia: they can only become aroused when they are involved in car accidents, or when they caress the wounds and bodies deformed by the collision of metal, glass, and asphalt. Scars become hieroglyphs in a new language of pain, the manifestation of an aesthetic of chaos and destruction achievable only through the intimate relationship between flesh and machine –while longing for the perfect crash.

In 1957, Roland Barthes wrote a text about the new Citroën DS –later included in Mythologies– in which he argues that cars are magical objects: new Gothic cathedrals, with traits akin to those ships from other universes that fed science fiction's imagination. If, at the beginning of the 20th century, only devotees of the Futurist avant-garde understood the car as a god –in his poem The Song of the Automobile (1908), Marinetti calls it "the vehement God of a race of steel"– Barthes warns that by the late '50s a large part of society already perceived the car as cathedral and goddess. But Ballard, who takes up Marinetti's ideas and Barthes' theories to introduce –through fiction– his own concepts about technique and speed, does not propose the automobile as a deity, but as a connecting device: a terminal, a way of linking ourselves to some kind of divinity. Neither god nor goddess: a sacred object of desire on the path to ecstasy; a fetish of a paraphilia that places sex and technique on equal footing; a cyber-eroticism that acts as a portal to altered states of consciousness and –together with kinetic energy– spins an invisible thread between technology and eroticism.

For the Futurists, speed was a kind of new moral-religion, the only way to contact the divine. Marinetti claimed that if praying was a way of communicating with divinity, then driving at high speed was a form of prayer –a fusion with the one true deity. Ballard, for his part, seemed to understand the Marinetti-type minds of the world when he said in interviews that his imagination was stirred by people who tear the veil of ordinary reality, transcend the self, and in a certain sense reach mythological states –something possible only through violent, brutal acts such as car accidents, which represent a collapse in the technological system with immense revelatory power.

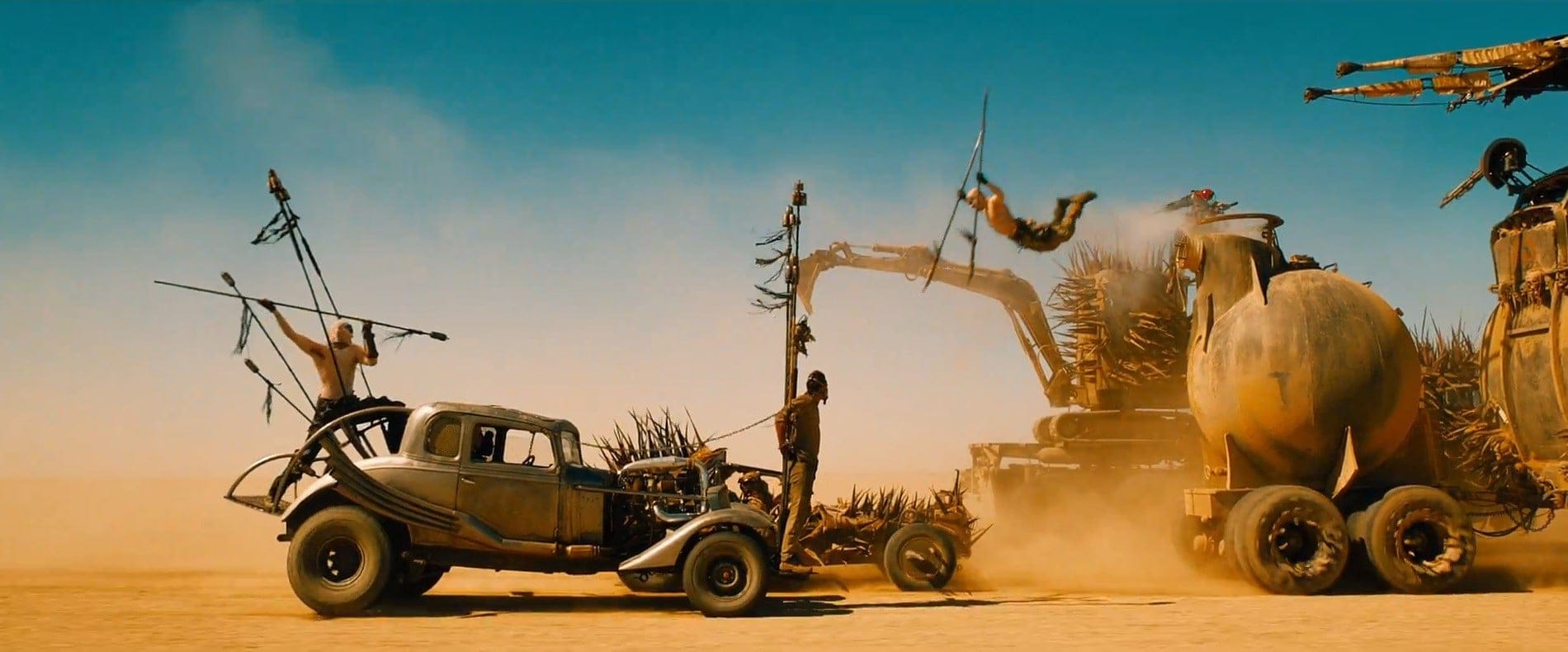

It is no secret that Ballard was a fan of Mad Max 2 (George Miller, 1981). In every interview he seized the opportunity to praise it and recommend it for its technical and narrative quality, but above all for the near and plausible future it proposes. There are many points of contact between the Mad Max saga and Ballard's apocalyptic fictions –The Drowned World (1962), The Drought (1964), and Hello America (1981): the destruction of civilization; anarchy and chaos after a global cataclysm; violence as the only method of survival; the struggle for scarce natural resources; and a Hobbesian war of all against all –tropes that make the two bodies of work feel like kin.

Fury Road (2015), the fourth installment of the Mad Max saga, gathers all these characteristics: environmental collapse after a nuclear apocalypse, extreme drought, titanic sandstorms, and a cult obsessed with speed –the half-life War Boys, faithful to the V-8, kamikazes who believe with religious fervor that dying in a crash on the Fury Road is a direct ticket to Valhalla. Martyrdom as a shared destiny, and violent death at full speed as a way to transcend reality and reach the warriors' paradise: the War Boys do not fear death; on the contrary, they desire it, as long as it happens on the road and another War Boy is there as witness and voyeur. There is no doubt: if Ballard had been alive at the time of its release, he would have loved Fury Road.

Post-Crash: Scrapping the Machine

In 1989, Japanese director Shinya Tsukamoto took Marinetti's and Ballard's ideas as artistic and conceptual inspiration and shot his debut feature, Tetsuo: The Iron Man. Filmed on 16mm in black and white –with clear influences from German Expressionist cinema– it became a cult movie despite its low budget and short runtime. Tsukamoto appropriates the Futurist love of the machine and cult of speed, but also Ballard's unhealthy symphorophilia, adding the mutilations and bodily deformations typical of body horror and a trashy cyberpunk aesthetic. The result is a film with Marinetti's spirit and Ballard's perversion, but in a Cronenbergian sci-fi context where the concept of the new flesh takes center stage: the symbiosis between human bodies and non-human entities –inorganic elements such as metals and different kinds of technology– producing a new hybrid being.

Tetsuo is an industrial opera in which one of its protagonists –who has an extreme fetish for scrap iron and metal, even inserting it into his own body– is run over in a fully sexualized car accident –shot with slow, sensual camera movements and scored with soft, romantic rock– by a driver who, after hiding the body, decides to have sex with his partner in front of the fetishist's dying corpse. The fetishist returns from the dead to curse him with a strange illness. Later, the cursed motorist realizes that metal is growing inside his body without stopping and that he can fuse with it, transforming into a new entity whose body completely blurs the boundary between flesh and metal. In the film's climax we witness a final duel between the two hybrid beings, who merge into a deformed monstrosity: a fast, metallic war machine, a supervillain that does not seek to destroy the world but to modify it –to transform it entirely into metal until it rusts into cosmic dust. A new world for a new flesh.

In 1996, David Cronenberg –the king of venereal horror, the architect of body horror, the priest of the new flesh– directed a film adaptation of Crash that, unsurprisingly, sparked controversy wherever it was shown. Francis Ford Coppola –president of the jury at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival, where it premiered– hated it so much that he refused to present Cronenberg with the Special Jury Prize. Ballard, who attended Cannes alongside the Canadian director and the cast, said the film was even superior to his novel. When it was set to be released in Argentina, after being censored in England and the United States, Gregorio Dalbón –current lawyer for former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, and at the time head of the group Familiares y Víctimas del Tránsito– filed an injunction seeking to ban its theatrical release, arguing that it glorified fatal crashes through highly aggressive scenes, increased drivers' collective violence, and promoted traffic-accident behavior as a means of sexual arousal. Of course, today it is a cult film, considered by many cinephiles among the best works in Cronenberg's filmography.

And in 2021 came the French film Titane (Julia Ducournau), indebted both to Crash's new flesh and to Tetsuo's fetishism. Its protagonist is a woman who, as a child, suffers a traffic accident that leaves her with a titanium plate in her head –after which she develops an extreme mechanophilia that not only leads her to have sex with cars, but also allows her to become pregnant by one of them and even give birth to a hybrid child, taking human-machine integration to the next level.

Latin AmeriCrash

The War Boys of Fury Road –fanatics of their own Futurist syncretic religion– pray before an altar forged from steering wheels and skulls before each suicide mission. That tabernacle, which symbolically fuses War Boy and vehicle, immediately recalls the altar of La Hermandad in the novel Thousands of Eyes (2021), by Bolivian writer Maximiliano Barrientos, where a cult that worships automobiles and speed seeks to awaken a dark deity through a suicidal driver who must crash his car –a Plymouth Road Runner– into a sacred tree in Bolivia:

What they called an altar was a wall in which there were bones of animals and human beings (…) bumpers, shells that at one time had belonged to a Buick and a Fastback. Steering wheels hung from chains that reached the ceiling, and spark plugs and cylinders and exhaust pipes emerged from that wall into which they had embedded license plates (…) photos of celebrities who had died in crashes: Grace Kelly, Jayne Mansfield, Linda Lovelace, Albert Camus, Isadora Duncan, T. E. Lawrence. One was of James Dean's corpse trapped in the twisted metal of his Porsche Spider. Eyes open, blood on the neck and forehead.

Barrientos draws on Marinetti and Ballard, but also on the body horror of Tetsuo: The Iron Man and Mad Max's post-apocalypse, and adds a Lovecraftian factor to the cocktail: cults, aquatic deities, portals that connect to other planes, cosmic horror. What emerges from that literary forge is one of the best weird Latin American novels of the last ten years: a story overflowing with black metal, speed, and violence, in which Barrientos makes the Futurist influence explicit by introducing a villain (the Albino, leader of La Hermandad) born in Milan (where Marinetti wrote the first Futurist manifesto), who in 1919 founded the sect in Detroit (the cradle of Fordism), and who has pursued –since the late 19th century– a deity reachable only through speed.

That same year as Titane's premiere, the story "Black Highway" (Perfect Parasites) by Colombian writer Luis Carlos Barragán was published. It takes up the idea of the human-car connection and twists it into something never seen before: in this fictional universe, automobiles are machine-animal hybrids –sentient and, to some extent, conscious beings– closer to an insect than to an Interceptor V8. The protagonist is a high school teacher who, exhausted by the bullying she suffers every day over her weight, buys a Tresauros 5 model car –beetle shape, spines, auxiliary pincers, eight retractable legs, three stomachs, and an irregular black carapace– and escapes, leaving her pathetic life behind.

Together they roam the highways with no fixed destination, until by chance they find a community to belong to: a savage band of insect-car tamers who live as nomads and hunt with their own vehicles, trained to kill other cars in order to feed on their flesh. The bond between the teacher and her beetle-car is deep and sensory: she pilots the vehicle through a hairy handlebar and a controller inserted into her mouth, and she drives naked, eager to feel the pores of the Tresauros's hide expanding against her skin and producing "spiritual orgasms". The driver-vehicle integration erases the boundary between human and machine; the Tresauros is an extension of the teacher's body and spirit.

The Man Rolls

In his essay The Medium Is the Massage (1967), Marshall McLuhan proposes a revolutionary idea: all media are extensions of some human faculty, physical or psychic. From a classical –but also cybernetic– perspective, technology is an extension of the body: the wheel is an extension of the foot, clothing an extension of the skin, electrical circuits an extension of the nervous system. Using the Greek myth of Narcissus –who, confused by Nemesis, goddess of vengeance, falls in love with his own reflection in the water– McLuhan supports his theory and claims that "this extension of himself numb[ed] his perceptions until he became the servomechanism of his own extended or repeated image". Thanks to these servomechanisms –extensions of the human body and mind– human beings undergo profound changes that transform them into man-machine, man-weapon, man-wheel.

In every story about wheel-men there is a symbiotic relationship between driver and vehicle –his "mechanical bride" (McLuhan dixit), his functional extension. In Paul Bartel's film Death Race 2000 (1975), Frankenstein (David Carradine) is the star racer of the ultra-violent Transcontinental Race, which awards extra points to drivers who run over people along the route –did someone say Carmageddon? The protagonist is the only survivor of the "mechanical crash of '95", with most of his body destroyed in car accidents and reconstructed through successive operations. For example, he loses a hand in a race and it is replaced with a mechanical limb –an extension that, besides giving him an advantage, connects him to his other extension –the automobile– in ways a normal human being never could.

In the comic Blue Arrow, by Rodolphe and Eberoni (1981), a similar story is told. Set between 1933 and 1939 in Italy, France, and Germany, it follows an American driver who, after a car accident, is left with the right half of his body unusable, and is fitted with an artificial arm that –far from being a disadvantage–wildly intensifies his symbiosis with the car: "In fact, instead of representing a handicap, my steel limbs give me an advantage! I feel infinitely closer, more in solidarity with my car than any driver has ever been! Our mechanics and our organs blend so tightly that, often on the road, I feel as if I've become a car!", says the iron man.

In the particular case of Crash, technology –the automobile– is not a functional medium but, on the contrary, the body's lethal deconstruction. The wheel is an extension of the foot, and the car is an extension of the penis –one that functions only through collision and impact.

In the opening lines of his epic poem Autogeddon (1991), Heathcote Williams –author of the first film script for Crash, which was never produced– seems to summarize the essence of apocalyptic fictions like Mad Max, Hello America, or Crash: "In 1885, Karl Benz built the first automobile. It had three wheels, like a disabled person's car, and ran on alcohol, like many drivers. Since then, more than seventeen million people have been killed in an undeclared war –and the rest of the world may be in danger of being run over in a final war for its oil".

The title of Williams's poem was probably inspired by a piece Ballard wrote in 1984 for the British newspaper The Guardian, titled "Autopia or Autogeddon?", in which he tallies car production from 1950 to 1980 and links it to the exponential rise in injuries and deaths among drivers and passengers. If the French dromologist Paul Virilio developed the concept of the "original accident" between 2002 and 2003, Ballard outlined a similar idea at least thirty years earlier: for Virilio, the original accident is the possibility of future accident inherent in every techno-invention –to invent the train is to invent derailment, to conceive the ship is to conceive shipwreck, to create the automobile is to bring pileups on the highway into the world. Ballard, for his part, wrote in 1971 that the invention of the car brought with it a chain of dangers and disasters –traffic congestion, serious injuries, and the deaths of millions in automobile accidents. In the prologue to Crash, although he did not yet define it as an "autogeddon", Ballard insists this is not an imaginary catastrophe but an institutionalized pandemic cataclysm that causes thousands of deaths and millions of injuries every year.

Even though writing the novel was a daily challenge –he had three children who were not immune to the possibility of a traffic accident on the congested streets of Shepperton– Ballard still insisted his work was exploratory and investigative, not moralistic. For the English writer, Crash and The Atrocity Exhibition were examples of novels that do not attempt to instruct or arrive at any moral conclusion –works devoted purely to pushing beyond an apparent dehumanization "in search of a new realm, with a new grammar and syntax, a new vocabulary, and a new way of perceiving the world".

In 1992, James Graham Ballard published in the magazine Zone a draft "glossary" for the 20th century in which he writes that humanity's greatest collective dream is made up of the millions of cars sitting motionless around the planet. An accelerationist dream shared by Karl Benz, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Robert Vaughan, and the entire automotive industry. A dream of speed, repetition, sex, and death.