My first encounter with Peter Sloterdijk’s philosophy came from a recommendation Agustina made to me: a very short but devastating text by the German philosopher, none other than Rules for the Human Park. In it, Sloterdijk reflects on Martin Heidegger’s Letter on Humanism, which he treats as the foundational text of the posthuman or transhuman movement. We’ll see.

Like any good German, Sloterdijk does philosophy by circling around questions raised by Friedrich Nietzsche and Heidegger, in a shared attempt to understand humanism as a philosophy, as a civilizing project, and as a tool for governing human wills. Back in June 2020, I devoted three episodes of Random Podcast to reading this text aloud. Several years later, with a lot of water under the bridge, it is still a remarkably significant piece of writing — even more so now, in the early days of debates around the massive use of screen-based devices, the role of reading, and the problems of learning, attention, and anxiety that come with all of it.

A few years ago, I also wrote (and later deleted) a tweet in which I claimed that, in the work of Nick Land, Curtis Yarvin, and Peter Sloterdijk, you can find several keys to understanding our era and its fundamental problems. Strictly speaking, this article is the second in that series: the first was dedicated to Nick Land, and especially to his Fanged Noumena. The one on Yarvin should probably have been the second, and this one on Sloterdijk the third, but I felt like jumping ahead.

Why do I think these three authors are worth reading? First, I don’t think you have to read everything they wrote, but rather a handful of specific texts that clearly stand out from the rest. This is especially true for Land and Yarvin (in his Mencius Moldbug phase). Their early texts are much stronger than what came after. In Sloterdijk’s case, I haven’t read enough to make such a sweeping claim, but the books and essays I have read are more or less consistent in quality. In any case, the problem of “which bibliography to choose” doesn’t, by itself, explain why I’m saying you should read these guys.

Second, maybe for most people it’s enough to stick with the classics: Nietzsche, Deleuze, Foucault. There’s nothing in Land that you can’t find in A Thousand Plateaus — which you should probably read — and there’s arguably nothing in Sloterdijk that isn’t already present in Nietzsche, more or less. However, I think both of them contribute more contemporary concepts and explicitly bring in the mental dimension. With the classic triad you can get far enough to think biopolitics; with these contemporary authors, I think you’re a bit better equipped to read the age of psychopolitics — a term we owe to that Korean thinker everyone loves to hate.

Third, then, dear Ruocco, what do we actually get if we play along and read these weirdos you’re proposing? Basically, Land gives us a theory of the reproduction of capital in contemporary culture and its capacity to self-reproduce — being the first to seek its own death while incorporating elements that might, at first glance, seem capable of replacing it. With Yarvin, we get an analysis of power that is miles ahead of the standard liberal one (the feral Rousseauians), and a sharper idea of which regimes are best prepared to withstand revolutionary assaults. He also offers a reading that is, at the very least, coherent — and at most, true — about how the internal dynamics of the U.S. government actually function, and what their (devastating) effects are on the rest of the planet. Finally, Sloterdijk gives us an account of culture as a device through which some humans produce other humans, with the explicit goal of optimizing that cycle. With three authors and maybe six or seven texts, we can assemble a halfway functional theoretical framework for understanding the contemporary world.

Rules for the Human Park

Rules for the Human Park was the first Sloterdijk text I read, and it is where he explores what will become of humanism as a concept — fundamentally, in light of the rise of mass culture and the arrival of radio and television. If the concept of “humanism,” associated with what we call the Enlightenment, has always been tied to a literate culture, what do we do when that condition breaks?

What do you do with a project whose very existence depends on the compulsory reading of certain texts — which in turn produce a certain way of seeing and thinking the world — when that entire setup is replaced by a new technology that breaks the conditions under which that project was viable? If you can no longer sustain the illusion of the nation as a community of readers, what remains? The Enlightenment — or rather, the humanist project — has always defined itself against barbarism. Think of the founding text of the Argentine canon, which is literally titled Civilization and Barbarism:

And here we must take into consideration the disturbing fact that savagery, today as always, usually appears precisely at the moments of the greatest display of power, whether as directly warrior and imperial crudeness, or as the daily bestialization of human beings in uninhibitory entertainment media.

That’s the question we’re left with at the end of the text, and it’s a question Sloterdijk doesn’t really answer — largely because no one has a fucking clue. What he does do very well is diagnose the becoming of the humanist project and what constituted it as such. That diagnosis can serve, at least, as a kind of orientation guide for whatever comes next.

For Sloterdijk, humanism’s permanent struggle is against the manufacture of “savage humans,” and it fights that battle through the power of the “right” readings. The humanist project, the formation of a canon, the dialogue between its intellectuals — all of that was always in the service of governing human affairs. It’s about managing two fundamental tendencies in humans, two flows: the inhibitory and the disinhibitory. It’s easy to imagine literate culture as a refuge of inhibition that makes “the civilized” possible — our mental picture of the Greek polis or the Roman amphitheater — while wild, unrestrained, disinhibited culture appears as the circus. The gladiatorial bloodbaths were the site of disinhibited frenzy and spectacle at once. It’s in this unbridled spectacle that the humanist project finds its rival.

In the postwar years, navigating precisely this dichotomy, Heidegger writes his Letter on Humanism, and with it — in Sloterdijk’s reading — inaugurates the age of the trans- or post-human. This path leads backward: first to Nietzsche and, finally, to Plato. Always Plato.

The first thing Sloterdijk highlights is Heidegger’s image of a kind of human pastoral, in which humans inhabit the world as if in a meadow, in mystical–contemplative communion with the other shepherds of Being. Humans as shepherds and neighbors of Being. An ultra–super–hippie vision (and, ultimately, also a bit Nazi).

But, as Sloterdijk asks, that shepherd in that meadow is still living in something like a house, a shelter. Drawing on Nietzsche’s sharp instinct, he finds a passage from Thus Spoke Zarathustra in which the mustachioed one, with his usual astonishing clarity, describes humans as the domestic animals of other humans. Human history is the history of the biopolitical complex house–human–domestic animal. The history of humanity, and of the humanist impulse, is the history of this domestication.

If we go even further back, we arrive at Plato and his concept of the polis in The Statesman, where he analyzes the nature of this “political animal.” Sloterdijk notes that Plato’s idea of a refuge for political animals sounds like a Disney park or Jurassic Park, but for humans. Which immediately leads to questions: who runs it, how is it run, and under what conditions are the humans inside reproduced? Are they the same humans who, thanks to their education or merit, become the park managers? Or is it a different type of human who is capable of ruling the park? The question of the human park is, in a way, the question of humanism. Or rather: if you push humanism to its basic “park” metaphor, what emerges is its thoroughly programmatic character — it is a way of reproducing, cultivating, and domesticating other human beings. And that is precisely what seems, in some way, to be in crisis.

Returning to the metaphor of the Enlightenment as a universal book club in which each member sends letters (books) to the others, Sloterdijk realizes that this image is in complete decline. At best, only a few archivists remain to store the correspondence that once was the canon — the training manual for human domesticators.

The question of governability and domestication is the question of power and of the existential horizon of humanity as a whole. Will we keep educating humans — for this? Or will we do it for something else?

Become Ungovernable: Rewilding as an Existential Horizon

Becoming aware that humans are the result of domestication by other humans is not something that naturally provokes joy or sympathy. It takes time to digest. It means realizing that we are, ultimately, products of the work of a group, an elite, a caste that has applied different processes over the centuries to make us what we are. It’s not even something that necessarily triggers inner rage; it’s more of a “it is what it is” kind of thing. It almost brings us back to that classic young-leftist line: “We are what we do with what they have done to us.”

But beyond slipping into self-help — a constant temptation whenever you write this close to philosophy — I want to look at at least two tendencies in reactions against the idea of domestication.

The first that comes to mind, partly because I devoted another Random episode to it, is the old and beloved Unabomber, with his manifesto against the industrial revolution and his random bombs. What Ted Kaczynski ultimately attacks are the mechanisms by which technological, academic, and governmental elites carry out the so-called “civilizing” process. The rebellion is then directed both at its effects and at its ruling classes. Basically, Kaczynski claims that by losing contact with the “power cycle” — procuring food and survival directly — humans have become oversocialized beings, prone to victimization and condemned to spend their lives in “surrogate activities” that serve only to compensate for the lack of connection with those power cycles. The post-industrial human, for Kaczynski, is garbage, and must revolt to recover what he once was.

In a similar vein, we find postmodern anarchist thinkers such as Hakim Bey, who advocates creating temporary spaces where people can experience freedom at least once in their lives; and in a much more radical key we have John Zerzan and The Pathology of Civilization, published locally by Walden. Zerzan directly locates the beginning of human domestication in the abandonment of hunting and gathering and the rise of agriculture. In a move that makes the Unabomber look moderate, Zerzan more or less claims that everything from agriculture onward has been a mistake.

In this context I can’t help but think of two meme currents, one of them summed up in “Return to Monkey” — going back to being monkeys, undoing evolution entirely. Not at all coincidentally, this meme compares the life of the domesticated hominid — who has to pay for bottled water and file tax returns every year — with that of his evolutionary cousin: the monkey, chimp, or howler who simply drinks from a river or eats a fruit from any tree without asking anyone for permission. It’s the state of nature versus the state of compliance.

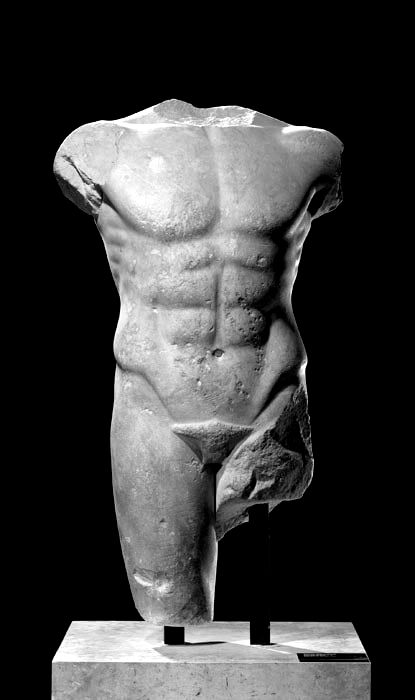

To this we can add another current, represented by the internet “philosopher” known as Bronze Age Pervert (BAP), who, in a less primitivist but equally confrontational line, proposes abandoning the current system — run by bureaucrats, technocrats, and lawyers — in favor of building a new Spartan-style aristocracy: trained, cultured, warrior-like. In Bronze Age Mindset, he sketches — half-ironically, half-seriously — a political program that questions the current human domestication project, carried out by mediocre egalitarians whose results are visible everywhere. That book, a major X account, and his constant promotion of training, gym bodies, and love between men turned BAP into a kind of guru within the “new right” ecosystem.

His journey doesn’t end there, of course. In proper right-Nietzschean fashion, he later released another book under his real name, Costin Alamaru: Selective Breeding and the Birth of Philosophy. I still owe it a proper reading, but in broad strokes it seems to be pointing at the same problem we’ve been tracking with Sloterdijk: domestication, the governance of humans, and the possibility of a form of education “beyond” classical humanism. Framed this way, the question is the same old one, but with heavy eugenic overtones, and easily assimilated to fascism/Nazism. The uncomfortable truth is that, no matter how much the question was weaponized in the early twentieth century, it remains as current as the Soviet gulags or the Chinese Communist Party’s “re-education” camps. The question of domestication is the question of the human — and that holds no matter when you read this.

In this sense, “becoming ungovernable” memes mark a fissure in the project of human domestication. And that’s why we like them so much.

Anthropotechnics and the Metanoetic Imperative

But our journey through Sloterdijk’s philosophy doesn’t end there. After Rules for the Human Park, I wanted to go deeper and ended up tackling one of his more monumental works: You Must Change Your Life. Here, the raw power hinted at in Rules is developed into a coordinated system and handed over to the reader.

What Sloterdijk lays out is the concept of “anthropotechnics”: the set of practices through which humans produce/domesticate other humans. We possess a whole battery of anthropotechnical practices whose central element is exercise. Sloterdijk defines exercise as an operation that yields an improvement, making it easier to repeat the next operation. Repetition is the key that links the “natural” and the “cultural” — a passage that is always open and always being reshaped through repeated reconfigurations. Think for a moment about everything we do: speaking, eating, cooking, working, going to school, studying. All human activity is grounded in repetition, and those who improve are those who train. Earth is the planet of exercising beings.

At the base of this anthropotechnical project is what Sloterdijk calls the “metanoetic imperative,” derived from metanoia, Greek for transformation. Citing Rilke’s famous line: “You must change your life.” You must improve your life; you must exercise your life; you must optimize your life. But the book doesn’t stop there: it unfolds a whole battery of concepts that articulate this anthropotechnical project — vertical tensions (the idea of constant ascent, the splitting of the human into strata associated with quality and hierarchy), and culture as a human immune system, divided into socio-immune systems and symbolic immune systems (memetic ones, Sloterdijk would say).

He also traces how the images that regulate the social archetype have changed. If, in the centuries after the Enlightenment, the crippled body functioned as the emblem of anthropotechnical transformation (culture as prosthesis), with postmodernity arrives the tightrope walker as the figure of the age: a person under permanent risk who only has to learn to hold their place and keep walking steadily. That is why athletes — who embody the metanoetic imperative and the notion of risk — are the most celebrated subjects of our time, models of humanity in every sense. Secular, ascetic, relentlessly trained, and successful.

One Last Conjecture

You might assume — as often happens in philosophy — that Sloterdijk is taking a “critical” stance toward all of this. But that’s not really the case. One of the most interesting things about reading him is that he seems less concerned with denouncing problems than with finding metaphors powerful enough to describe the world. The concept of anthropotechnics, tied to exercise and to the idea of a symbolic immune system (a connection that would deserve its own article), is a strong one: it gives the reader a kind of temptation toward self-help, or better yet, a sense of operational capacity.

What Sloterdijk’s book doesn’t do is denounce domestication and then go looking for some fantastical, primitivist escape to an idyllic past, nor does it try to exploit the concept to propose a new ontological aristocracy. Sloterdijk seems content with having exposed the trick: pointing out that even in the processes of human self-recreation there is a possible design space. In the last fifty pages, he makes an effort to sketch something constructive with the tools he has laid out. Tying back to the earlier question of humanism and the Enlightenment, he proposes some kind of planetary coordination toward a shared anthropotechnics that would unify humanity under a single civilizational project. But given that he devotes less than ten percent of the book to this, it’s clear that his heart isn’t really in the blueprint.

Designing an anthropotechnics is, quite simply, the ultimate political project. It’s not about concocting or remixing a set of ideas but about establishing a series of exercises that, through repetition, generate a desired scenario. I’m almost certain that, without a doubt, the future of politics will be decided on this terrain.