A few years ago I started buying second-hand clothes and became a vintage enthusiast –an addiction I've had to rein in amid Argentina's Milei-era downturn. Vintage here means acquiring and collecting past-season designer garments, a practice that has surged into a bona fide phenomenon in recent years. It's fueled by a cluster of epochal anxieties and desires: a push for sustainability in the fashion industry; the existence of an almost inexhaustible archive of collectible pieces; nostalgia's capture of the present –symptom, in part, of our fatigue at imagining the new and the future–; and the craving for singularity, intimacy, and storied objects in a homogenized world whipped by FOMO and fleeting trends.

Yet vintage's champions often skip an awkward truth: the practice relies deeply on material and symbolic inequality. I want to probe those dimensions and situate collecting on a triple hinge –nation, class, and status– within contemporary capitalism. As telegraphed above, I'm setting aside a broader and far more beneficial practice that often gets lumped under "vintage": thrifting for well-made, well-designed used clothing with an eye to quality and the environment.

Fashion and Nation: The Fabric of Dependency

There is no vintage –nor fashion more broadly– without deep asymmetries between poor and prosperous nations. The obvious comes first: we've long been shown luxury's dark side, where garments are manufactured in the Global South –or even in great powers– under dire labor conditions. Add to that the fact that many wealthy countries, having increased clothing consumption by roughly 60% over the past fifteen years, export their textile waste to poorer nations, generating pollution. Africa is paradigmatic here, though hardly unique.

This "geopolitics" of dress isn't new. One Argentine thread linking clothing, politics, and Nation is woven in the nineteenth century. We largely owe it to the 1837 Generation, especially Sarmiento's Facundo, which knotted fashion to the axis of "Civilization and Barbarism". Of the cities, he writes, "the comforts of luxury, European dress, the tailcoat and the frock coat have there their stage and their proper place". In the desert that surrounds and oppresses them, the "uncultivated plain" lacks those manners and assaults them. Sarmiento pushes further in his liberal rhetoric about dress:

"There is more still: every civilization has had its costume; and every change in ideas, every revolution in institutions, a change in clothing. One costume for Roman civilization, another for the Middle Ages; the tailcoat begins in Europe only after the rebirth of the sciences; fashion is imposed upon the world by the most civilized nation… Argentines know the stubborn war that Facundo and Rosas waged against the tailcoat and against fashion. In 1840, a group of mazorqueros [Rosas's political enforcers] surrounded, in the darkness of night, a man walking Buenos Aires in a frock coat."

Rosas versus nineteenth-century fashions: an early culture war. Exactly a century later, a new political event rekindled that liberal imagination of Civilization and Barbarism –and reopened the textile dispute. The initial subject of Peronism is the descamisado who surged into the public square on October 17, 1945, marking clothing as part of the event's impact.

Soon it would be Eva Perón who concentrated in her body and image the growing relevance of fashion –amid expanding political propaganda and mass communication. Evita's singularity, so unlike previous First Ladies, captivated Argentina and the world with iconic dresses and suits. Christian Dior's famous line is telling: "The only queen I ever dressed was Eva Perón". To understand Evita's full link to fashion, we must also add the Argentine designer Paco Jamandreu, who handled the simpler pieces for her political work as a "minister without portfolio", as Perón described her.

Yet, as with any force of that magnitude, Evita's political calling sat uneasily with the insider aura of high fashion. Her love for the descamisados and her Christian outlook meant that, at times, her taste for luxury clashed with the harsh social realities she tended to –tension that could harden into conflict. In Mi mensaje, her most combative text, she leans toward contempt:

"I clothed myself with all the honors of glory, vanity, and power. I let them adorn me with the finest jewels on earth. Nations everywhere paid me their tributes. Many times I held before my eyes, at once and face-to-face, the misery within grandeur and the grandeur within misery. I never let them tear from me the soul I brought from the street; the splendor of power never dazzled me, and so I could see its miseries."

No one who truly loves fashion can inhabit a relationship with it free of conflict or defections. Perhaps Evita "resolved" that fracture with an idea of luxury for the poor. Her vision for social aid homes –and her intensely personal bond with those most in need– are well known. Far from Dickens's ochres, Peronist welfare and its institutions staged a sumptuous celebration in the logic of the gift. In La razón de mi vida she writes:

"That is why my 'homes' are generously rich… In fact, I want to go overboard. I want them to be luxurious –excessively luxurious. I don't mind the obligatory visitors who clutch their pearls and, with polite phrases, ask: 'Why so much luxury?' or almost naïvely wonder: 'Aren't you afraid that when these descamisados leave here they'll get used to living like the rich?' No, I'm not afraid. On the contrary: I want them to get used to living like the rich, to feel worthy of the greatest wealth. In the end, everyone has the right to be rich, in this Argentine land and anywhere in the world. The world holds enough wealth for all to be rich."

This passage stands out for its candid, hopeful vision of the material world –one that would furrow the brows of those who intone Remes Lenicov's aphorism ("Politicians always want more, but in economics there's no magic"). Still, other economists would concede that mid-twentieth-century conditions were, in many ways, better for those at the bottom than today.

Either way, Sarmiento in the nineteenth century and Evita in the twentieth form a binding ligature of Argentine identity: our relationship, approach, or struggle with global poles of economic and cultural power.

Fashion and Class: Everyone Will Hear Your T-Shirt

Center–periphery dynamics alone can't explain how fashion works inside societies –especially from the late twentieth century onward. Nations carry their own internal "underdeveloped" zones, their homegrown barbarians; today's culture wars play out there as well, and fashion is one of their contested terrains.

Donald Glover's series Atlanta is among the sharpest interrogations of Black status in recent decades. Season 2, episode 10, "FUBU", shows a Black middle-/working-class kid who, in the mid-'90s, goes to the mall with his mother and wanders off among the racks. He stumbles on a prize: a FUBU jersey emblazoned with a big "5". As Tracy Chapman's "Give Me One Reason" plays, his excitement is underlined; he runs to ask his mom for it. The next day he heads to school enchanted with his new T-shirt, drawing praise from classmates. Through quick scenes, Glover sketches the rule-set for those kids: hierarchies, severity, and disciplining violence that police which attitudes are possible in that microcosm.

In class, Earn's "exclusive" T-shirt wins nods from an alpha boy and the pretty girls –until another kid walks in wearing the same shirt, and the jokes start about which one is fake. The room laughs; both boys insist theirs is real, though Earn knows his isn't. The popular crowd pushes the dilemma: only one can be authentic, and the kids must prove which. Authentic vs. fake structures the rest of the episode –and reverberates across the series– as the shirt becomes a proxy for money and for "success" with girls. Bullies close in on Earn; he persuades them it's his that's original, knowing Devin –the one in the knock-off– will be singled out for sustained ridicule. In a tragic turn, Devin dies by suicide, crushed by mockery and family trouble.

The episode's stroke is to magnify an already hyperbolic children's world, where banal signs carry outsized weight in circles of belonging. More specifically, "FUBU" shows how parts of Black America are intensely bound up with fashion as a status marker. In one scene, a worried Earn tells a white friend, "If it's fake everybody's gonna clown me –give me nicknames", to which the kid replies, "Doesn't seem that important –I've worn this shirt twice this week." It reads like a coming-of-age tale in symbolic capital through textiles: clothing as an early trench where the complex system of inclusion and exclusion –in this case racial–materializes and takes shape. In the "This Is America" video Glover deadpans to camera, "I'm on Gucci / I'm so pretty / I'm gon' get it / Watch me move", while cops sprint and Black bodies are chased and killed in the background.

Capitalism and Vintage Distinction

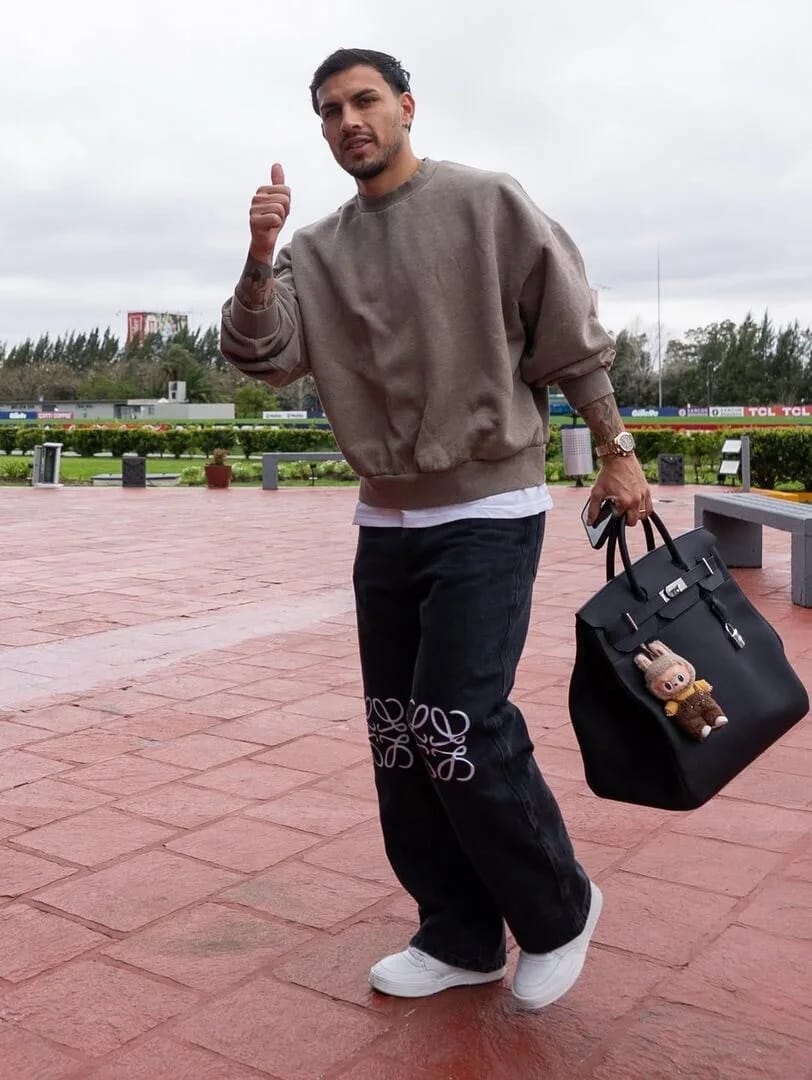

The boom in vintage collecting connects, in several ways, to those nation- and class-bound dynamics. First, because the so-called First World has staged a mass-market simulation of luxury, loosening haute couture from its old-guard class circuits where economic status, symbolic capital, and lineage were tightly buttoned together. Today it can be enough simply to have the money. You no longer need aristocratic credentials of taste or manners: Gucci can dress a rapper from "the hood", Hermès a footballer from a "developing" country, any breakout streamer can flaunt Louis Vuitton. A propaganda-grade rupture with older barriers lets money trump class, as fashion becomes a social sign of victory in the success race –within an ideology that treats power as non-zero-sum and insists "we can all make it".

In that context, vintage becomes a hunt for lost aura: the singular find only some can secure, thanks to savoir-faire and access to luxury archives. It reproduces the classic flight of the rich to zones not yet overrun by the masses. It also signals an exhaustion of aesthetic imagination in societies best seated in the capitalist amphitheater. The foreclosure of the truly new –so central to Mark Fisher's reflections– returns as an obsession with repeating what's preserved, looping the feeling that "the best is over" with a Funes-like incapacity to forget (Borges's Funes the Memorious), even as the loop spawns new phenomena.

No small part of this is the trade war with China, a country that has turned pre-assembly work and supply-chain opacity into a weapon –putting a Birkin or a Chanel within arm's reach and, via TikTok, directly in your hands. Vintage presents itself as a way back to "the West": through brick-and-mortar boutiques endorsed by models or fashion magazines, and through platforms out of Silicon Valley partnering with "pre-loved" fashion (e.g., eBay with Vogue). Vintage practice has also become a way to park value in "safe" goods –and a way to resist the overwhelming Chinese apparatus and its mass production, perceived as homogenizing, anti-ecological, and shoddy.

As a romantic ode to authenticity and quality, vintage can read like a reactive turn back to the durable and the valuable. The ecological dimension –imperfect but not baseless– draws on countercultural imaginaries wary of consumer frenzy and committed to reuse and recycling as ways of relating to others and to the world. But that dimension falters when vintage re-plugs into a fashion industry that has hardly softened its polluting footprint or the harsh labor practices it has dispensed for decades. Nor can vintage do without the constitutive elitism of distinction itself.

I know and reflect on all these frivolous, alien, even shadowed edges –and I still do it. I take long bus rides to the Desperate Housewives-style homes of the northern suburbs of Buenos Aires to pick up that Armani skirt or Max Mara dress I unearthed after endless online searches at a ridiculous price. That's where my pleasure lies: the affordable thrill of the expensive, the wearying labor of finding the "easy" lever that unlocks the difficult. Maybe it's the same magpie spark that lit up in Evita the first time she touched a Dior; the same that flashed in Earn when he found his FUBU.