“Nothing read there can be repeated without risk; yet no one who has visited it can forget what they glimpsed among shadows and forbidden manuscripts.”

(Leopoldo Lugones, The Infernal Library, 1906)

A library can be a gorgeous, outrageously expensive oak bookcase; a whole building; a few planks propped on bricks —like the one Homer Simpson builds in the episode where he goes to college— or even the floor of a room. A library can also be an altar of knowledge, a collection of objects, a forbidden place (as in Lugones’ story), or a playground. Strictly speaking, a library isn’t the furniture or the building —it’s the space where books are kept. Over time, that idea expanded as new technologies introduced new formats and the notion of an archive system.

In that sense, the place where books and files accumulate becomes an entity with its own aura —born in your home, living somewhere between chaos and order, and sustained by you. But there are many types of libraries: some are built by design, others happen by accident. By design, I mean a collection shaped by a concept or a curatorial intent. By accident —well, books used to pile up at home through school, inheritance, or pure chance. For all those reasons, I think there’s a special spirit in these places.

I was lucky: in my childhood home there was a library filled with history books, science fiction, encyclopedias, and other oddities. Before the internet, your first window onto the world often began with whatever you could find within your own walls: records, VHS tapes, books, clothes, objects, and so on —things that belonged to your parents, grandparents, or other relatives. If you were curious like me, you searched every nook for something new to play with, and some of my favorite places were the shelves at home and at my grandfather Bernardo’s.

When I was little, people gave me books: storybooks, Where’s Wally?, and the Billiken library collection. I had it hanging above my bed, and one day —when I was seven, give or take— it fell straight onto my head while I slept. I grew up learning what it meant to have a library, how to care for it, and that collector’s itch to build sets and series. But as I got older and met more people, I began to see that piece of furniture as something else, too: on one hand, a window into someone’s interests and obsessions; on the other, a status symbol for those who want to prove what they know through what they’ve read —or what they want you to think they’ve read.

So what, exactly, is a library?

“A library is a living organism. It’s not something static, or just a piece of furniture with objects inside. It’s something we have to feed and care for”, says Nadia Buckmeier, a librarian at the National University of La Plata. I loved that idea, because it connects directly to what I said about a space with its own aura —something you can seek out and build intentionally, or something that simply appears through accumulation.

Books are what animate that living-organism concept. A personal library can change without you noticing: through the texts you curate and treasure, the books people give you hoping they’ll land, and the rotation of what you donate, sell, or pass along. In that way, a library is an archive, a living organism, and a cross-section of your mind —a snapshot of what you find interesting. Archives matter for understanding who we are. And even in a digital era, choosing to preserve and defend physical books is a political stance.

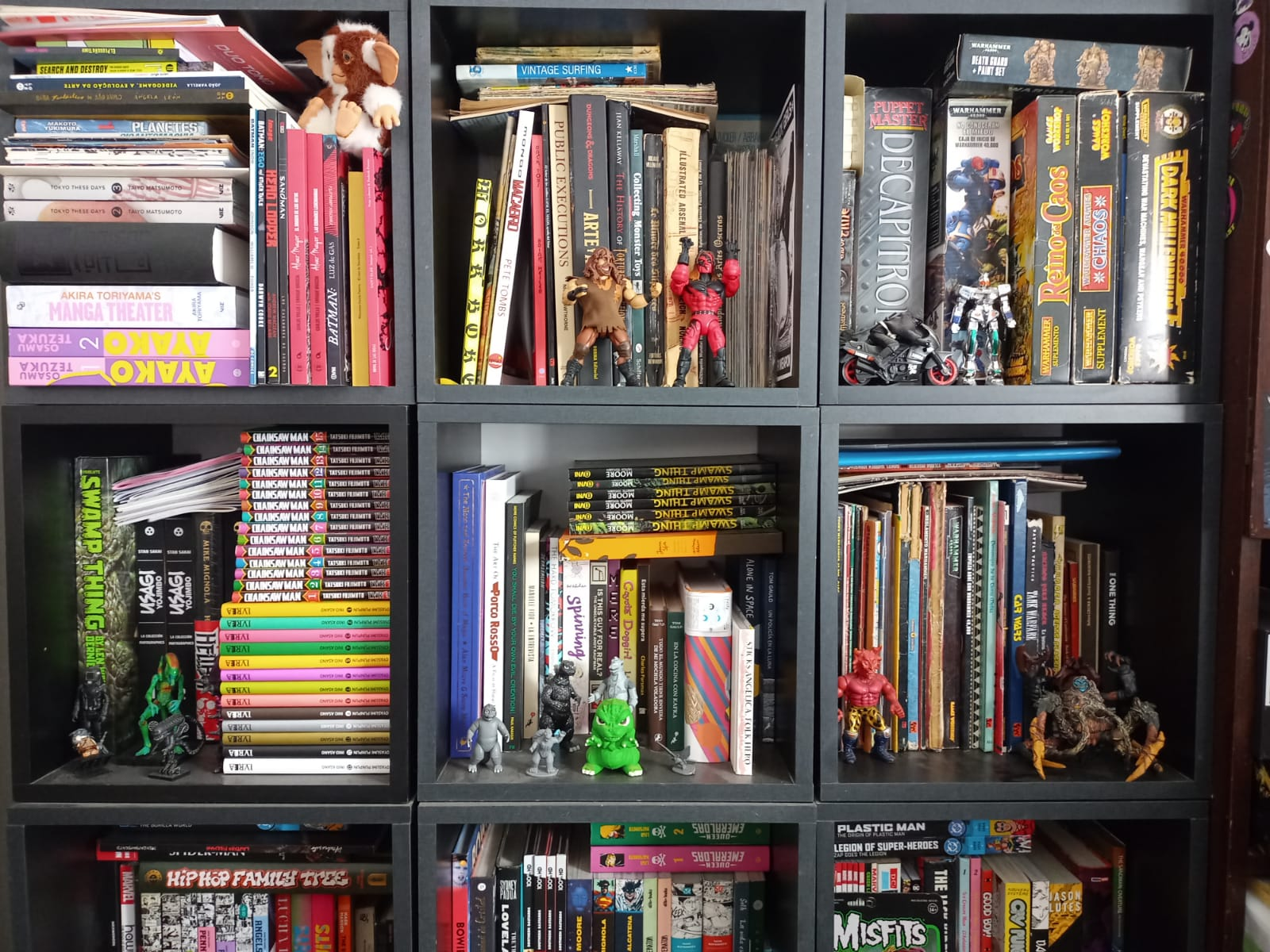

In Lugones’ story, the library is a space of forbidden knowledge —preserved, but also censored and hidden. I find that idea fascinating. I’ve written in different issues of Colección 421 about how to relate to collecting, and one side I wanted to highlight here is the curatorial one. My approach to collecting has changed over time. I’m no longer interested in having a lot (or all) of something, or in chasing the most expensive, exclusive version. These days, my choices are guided by something as capricious as taste, but also by whether the objects I add have a story to tell —whether it’s the object’s story, or how it found its way to me.

With that in mind, my library has mutated over the last few years. The classics I’d read aren’t there anymore, and neither are the boxes of comics. I’m not interested in owning dozens of floppies; now I’d rather have the one original issue that can stand in for a whole era on my shelf. That’s how I ended up building my own infernal library, Lugones-style: a collection of rare, forgotten texts, and books that matter to me for personal reasons.

Among the curiosities in my infernal library is a numbered edition of La Guerra Gaucha by Leopoldo Lugones, signed by his son. Books on occultism, magic grimoires, and volumes on armaments coexist with local fanzines, comics, and manga. My shelves don’t hold the complete works of my favorite authors, or the standard literary classics. Instead, they feature things like an illustrated guide to public executions, or the massive Mondo Macabro film encyclopedia.

Maybe this reads like an old man yelling at a cloud, defending the physical format. Maybe it’s even a snobby piece about how important it is to own books. But to me, continuing the tradition of books —and making room for them at home— still matters. This Christmas I gave my niece, almost two years old, her first little bookcase stocked with twenty tiny storybooks. My sister tells me she spends loads of time playing with them. And one day she’ll inherit the Where’s Wally? books that my sister and I practically wore out.

It matters to keep these spaces at home —to visit neighborhood and community libraries, and the big ones too— but above all, to keep curiosity alive through books and the desire to learn. Because, as G.I. Joe put it: knowing is half the battle.

EN

EN