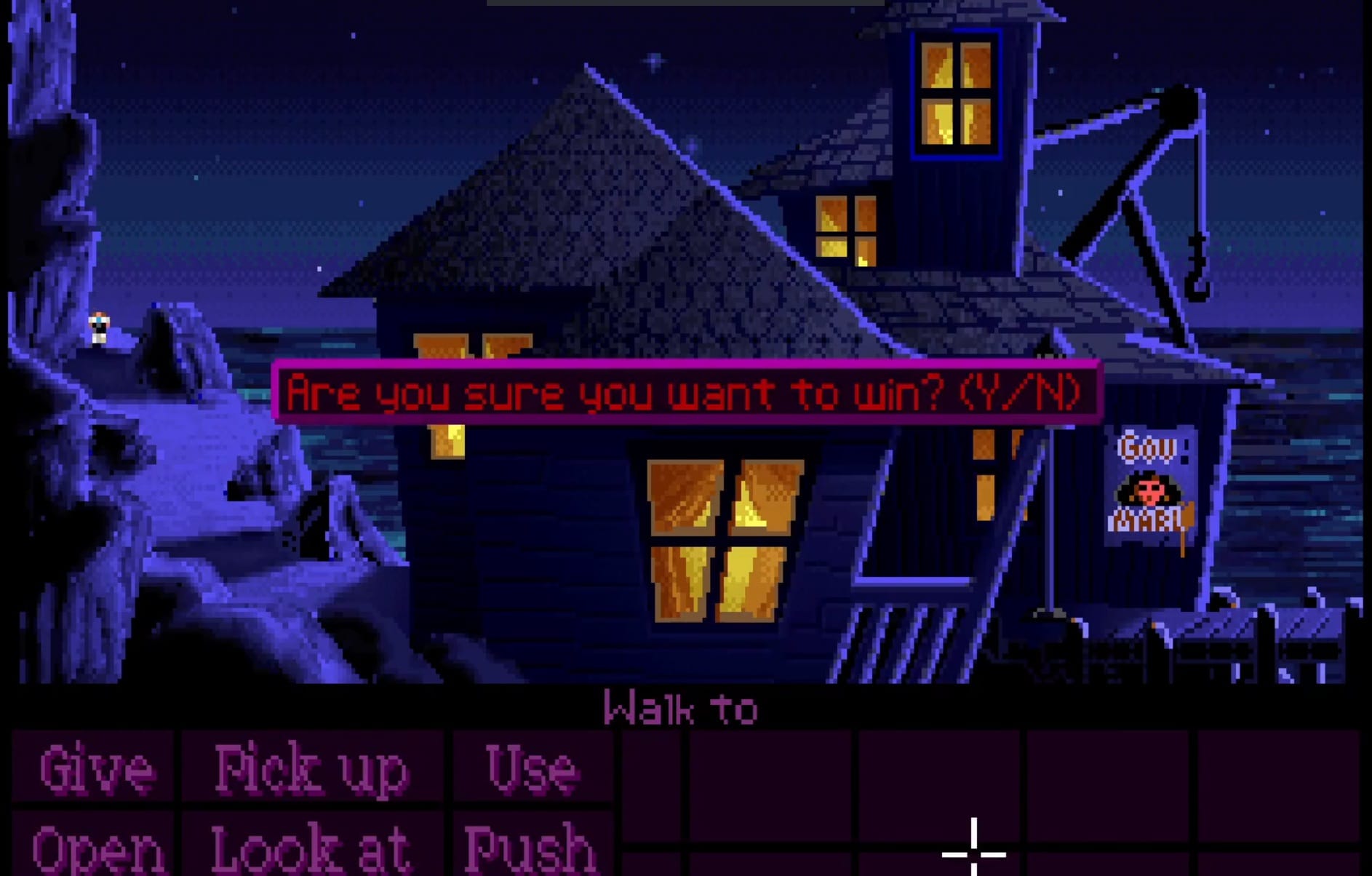

In 1990, one of the most beloved games among DOS players came out: The Secret of Monkey Island. A graphic adventure that leans more on story and puzzles than on raw gamer skill. Without getting into the game itself, which deserves its own article, the first Monkey Island has a curious detail: at any moment, if you press Ctrl + W, it asks whether you "want to win". If you hit "Yes", it tells you "You win" and that you scored 800 out of 800 points. The game doesn't have a scoring system; it's all a joke. It shows you an altered version of the credits, played for laughs, and you have to restart the computer to exit. The laughter is massive; the sense of having really "won", zero.

If we understand it as a gag, did you actually complete the game? It doesn't really feel like it, because you skipped all of it, and this ambiguity applies to a thousand other games. In Donkey Kong, the 1981 arcade, after clearing four stages the game loops infinitely until a memory error kills it. There are no end credits; the whole experience isn't designed to "end" in a conventional way. The 8-bit Super Mario Bros. actively invites you to skip levels via warp zones so you can reach the final castle and rescue the princess. And once you finally find Peach, the game simply starts over, without any real sense of closure.

Internet and Video Games' Magnetism

Finishing a game is ambiguous, because feeling "satisfied" with the experience you just had is undeniably subjective. That's why some of us can spend 10 hours straight in front of a PlayStation while others play two matches of FIFA at a barbecue and don't touch a controller again until the next get-together. It's been like this since the birth of video games and well into the 2000s: you bought a game, took it home, and did whatever you wanted with it; you played at your own pace and in whatever way you felt like.

As in so many other corners of modern culture, everything flipped with the popularisation of the internet. Suddenly, you stopped playing alone. Even some of the most popular titles had an online component they leaned on or straight-up depended on. So a metric like "copies sold" became less relevant when measuring the success of a game that now needed to be sustained over time. The key was engagement: how long do you stay connected or interacting with the thing? Does the game manage to pull you back in every single day? Do you toss it a couple of gems or coins for a new skin? What matters is that you keep coming back, that you keep playing.

By the late '90s there was already a whole lineage of games where you connected to the internet to play with or against other people, and some of them took giant steps toward turning that niche into something mainstream. Quake II, Warcraft II, StarCraft, Age of Empires, Diablo and so many others got players yelling at each other over LAN parties, and then all that moved online, where you no longer had to lug your PC over to someone else's house. Later came experiences like Ultima Online, games that only worked when you were connected to the network, and that was the seed that eventually inspired World of Warcraft and Final Fantasy XIV, two of the most-played MMORPGs around today.

Consoles eventually caught up. The first to come with a built-in modem –not as a separate peripheral, but as an integral part– was Sega's 1998 Dreamcast which, even though it only existed for a little more than two years, was the spearhead for everything that would follow. Then the first Xbox positioned itself as a kind of spiritual successor, making the same bet; and later on, the Xbox 360, PS3 and Wii all had their own takes on online play, introducing the idea of "profiles" you would log in with that showed your username, tag or whatever. If you were good enough, your handle could start to command respect or admiration in certain communities, because you were a beast.

Games changed because the possibilities of the network even reshaped how they were coded, conceived and sold. The contrast is obvious, and things that were a scandal in the early days of online gaming are now completely normal. For example, the "horse armour" downloadable content (DLC) for The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion left players scratching their heads: how could they charge you five dollars just to "dress" your horse in armour that doesn't even do anything? By contrast, these days we're grateful if DLC is purely cosmetic and doesn't lock you out of chunks of game content.

Before the advent of the internet and online gaming, business logic said the most valuable player was the one who bought the most games. But there's a catch: there are tons of companies making games. What makes players buy yours? Why should someone who plays Assassin's Creed go pick up another Ubisoft title instead of heading off to play EA Sports FC, Call of Duty or Dark Souls? DLC shifted that commercial logic, and suddenly it became crucial to keep players inside the game you had already sold them, so you could later sell them more cosmetics and expansions or simply keep them invested and talking about the series until the inevitable sequel arrived.

The Invention of Achievements

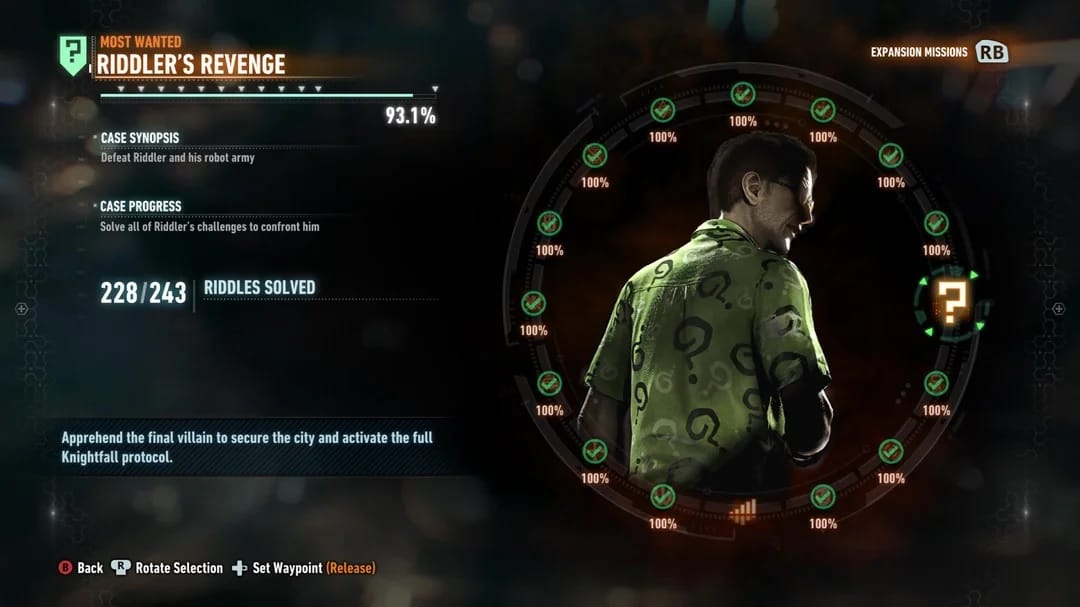

That's when, in the Xbox 360 era, Microsoft had an idea: give players a reason to complete absolutely everything at 100%. Enter achievements, which tweak the old arcade logic of "getting the highest score" and turn it into a set of broader, cumulative goals tied to your profile. The console gives you a global "gamerscore", depending on how much you play, for completing objectives. Earning every achievement might mean hitting certain story beats, visiting all the locations, playing in specific ways, finishing the game under a time limit, and more. The goals are as varied as the designers' imagination for "gamifying" the fact that you're playing.

Initially, every Xbox game awarded up to 1000 gamerscore points for completing it under all the conditions it proposed, which often meant replaying the whole thing, whether it lasted six hours or a hundred. That tidy 1000-point logic has since broken down: today some games are much more "generous" than others, and there are communities that pick what to play based on the total score on offer. The achievement system set such a strong precedent that, not long after, the PlayStation 3 rolled out its own "trophies", crowned by the coveted platinum for hitting 100%. Even Steam, the dominant platform for PC gaming, added its own achievements. The only major hold-out is Nintendo which, beyond the odd internal tracker inside a game, still doesn't have anything quite like it at system level.

Within this framework, we circle back to the initial question: what does it mean to "beat" a game? Because now watching the credits doesn't necessarily mean anything. A lot of optional content only shows up after you "defeat" the final boss and new areas unlock, or when you jump into a "New Game+" with all your previous gear. It literally varies from title to title. A halfway satisfying answer, at least for some players, is to have earned 100% of the trophies or achievements. The logic goes: if you've seen and done everything, there's truly nothing left for you to do.

Compare that with the early 2000s, when you could buy three PS2 games for 15 pesos and just toss the one you didn't like. Today a game can cost 70 USD or the equivalent in your local currency, be free-to-play (but monetised via microtransactions), or exist as something a bit ethereal, available only as long as you keep a subscription active. Peak FOMO: play everything, and play it now, or you're wasting money. In that context, ticking off every achievement feels like a way of convincing yourself you "got your money's worth", even if it's basically just a pat on the back from the developers saying, "Nice one, you pulled it off".

The Psychology of Gamerscore

Playing with your eye glued to gamerscore, trophies or leaderboards might sound silly, but psychologically it works, and it definitely gives some people a sense of satisfaction. "We can understand the desire to complete a video game both as a personal trait and as a compulsion that functions as a symptom", says psychologist Silvia Mirta Ciacciulli. "Desire is always organised around lack: the subject desires because they are traversed by a structural lack, by something impossible to fully satisfy. In this sense, the desire to platinum a game can be read as a fantasy of completeness, where the platinum appears as an object that could fill that lack and give a feeling of wholeness. That 100% would be a way of reaching a complete state, impossible for the subject as such, which would also bring an end to desire."

Psychologist Leandro Javier Napoli adds: "The mind tends to generate patterns where there are none. It's a survival mechanism. The feeling that something's missing activates this 'something's wrong' response and pushes us to complete it. In psychoanalytic terms, we can also talk about neurotic structures, so it's not the game itself that we want to platinum but an egosyntonic experience for the self. I also wouldn't underestimate the competitive factor of seeing yourself in the tiny percentage of people who actually pulled it off".

However, even if "platinum" stands in for a search for fulfilment, it doesn't necessarily work. "Once it's achieved, the subject comes up against the void again, because desire is never truly satisfied; it only shifts to a new video game. We could say that the desire to platinum a game can take on a compulsive quality when the person feels driven to repeat the act without being able to stop, even when there's no longer any pleasure in it. At that point, it's no longer a symbolic desire oriented toward lack, but a compulsion governed by the repetition drive, where enjoyment lies in the act of completing itself rather than in the result", Ciacciulli notes.

So does that mean you're sick in the head because you got obsessed with Batman: Arkham City and finished every single Riddler challenge? You are absolutely a maniac –you are– but calling you "ill" is a stretch. "When we say 'pathological' we're talking about illness, like gambling addiction. If the trophies are also tied to pay-to-win mechanics, then we're dealing with an unethical business practice aimed at generating addiction. Even when it doesn't reach that level, it can still be egodystonic: if you notice you're no longer enjoying the game itself and it turns into a need that keeps you from sleeping, puts you in a bad mood or stops you from playing other games, that's a red flag", Napoli adds.

"A symptom on its own doesn't make a pathology", Ciacciulli concludes. "In and of itself, completionism isn't pathological. For it to be, we'd have to see obsessions and compulsions in play. Something that must always be there for us to talk about pathology is that it causes significant suffering in the person, and that it limits their life. If it doesn't generate distress or anxiety when you leave things 'unfinished', we're not looking at a clinical condition."

Picture two players in separate rooms. One is on their fourth match of Battlefield 6. The other is grinding away at Crypt of the NecroDancer, trying to unlock the trophy that asks you to use every character in a single, flawless run without upgrades or save points. Which one is having more fun? To answer that we don't need to keep writing; we just have to ask them. Each player is the only one who really knows what entertains them.