The Star Wars prequels trace the path from Anakin Skywalker to Darth Vader –yes, that's why we're here, fair enough. In one sense, Anakin mirrors the arc his son Luke will later follow: he seems to rise "from nowhere" to become the figure on whom the cosmic order rests, a crusader for a new galactic paradigm; he has a natural gift for the Force; and love plays a decisive role at the end of the trilogy.

But the parallels end quickly. Anakin does emerge "out of nowhere" –from the Force in its pure, formless state, like Jesus born of Mary as a divine miracle– whereas Luke's "nowhere" is metaphorical: a boy from a no-place (Tatooine). Anakin becomes the champion of the Dark Side rather than of the Force as a harmonious order the Jedi are sworn to uphold. And love in this saga sits "beyond good and evil": Luke's love of life is strong enough to forgive his genocidal father; Anakin's love curdles into fear of loss, the wound through which Palpatine's words worm their way toward Darth Vader.

If you didn't get this off the bat the first time you watched the prequels, don't worry –our aim isn't the esoteric, quasi-Jungian, quasi-Zoroastrian cosmology where the franchise wavers between a dubious pantheism and a straight Good-versus-Evil story. Our concern here is political theory –constitutional law. Because the prequels are also the story of a democratic republic’s collapse, and –unfortunately for everyone involved– a collapse that hangs together all too coherently.

Hypothesis: the Galactic Republic Was a Confederation

Who's the true protagonist of the prequels? Anakin, Obi-Wan, Padmé? They are, of course –but if one character quietly sits at the center of everything, it's Sheev Palpatine, Darth Sidious, the Emperor of the Original Trilogy. In the first film he is simply the senator for Naboo, a small planet represented in the Galactic Senate.

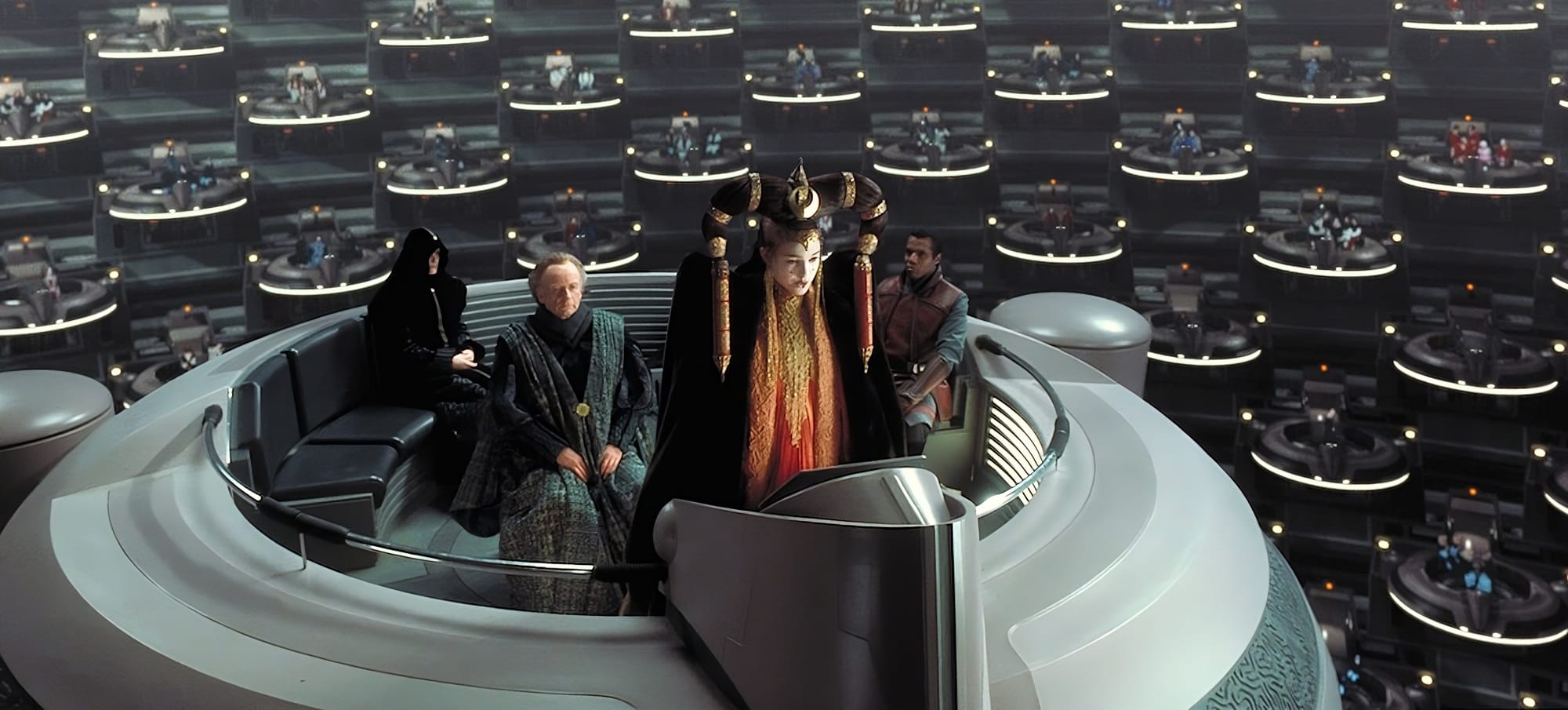

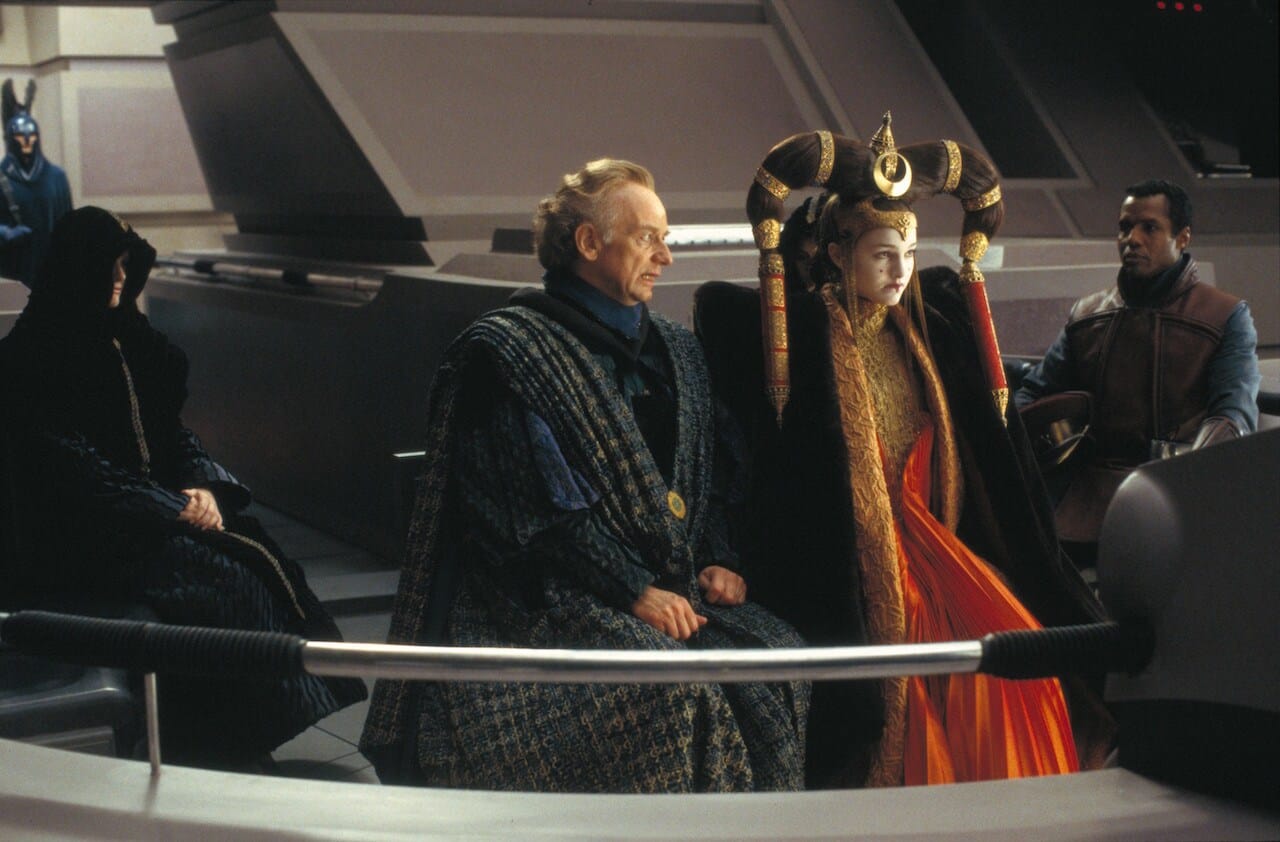

In Episode I, the Galactic Republic, for descriptive purposes –and drawing on the lessons of A. V. Dicey– reads like a confederation. There is a Senate where each seat represents a planet, sector, or major interest group (the Trade Federation, the Banking Clan, etc.), but there is no parallel lower house –a chamber of deputies. It's the minimal democratic state in terms of centralization: political units enjoy broad autonomy. However populous one world may be, each world counts equally as a world and gets one vote in the Senate.

Scale matters. The Swiss can manage a stable confederation partly because they are few and relatively compact. Territorial extent and population are the founding variables of federalism and representative politics. Athenian democracy and the Roman Republic are lovely, but –as Hobbes reminds us– modern polities rule multitudes across vast distances. As Hamilton and other American theorists argued, the problem with confederations –state leagues like the Delian League– is that, to quote Qui-Gon Jinn, "there's always a bigger fish". Even within the same pond of political union, stronger autonomous units (Macedon –or the Trade Federation) can subdue –militarily if need be– smaller ones (Thebes –or Naboo).

Institutionally the Republic has a Senate (of states that often backstab one another), a bureaucracy, the Jedi, and a Chancellor –Valorum– whose role resembles a prime minister's: chosen by the assembly, relatively weak compared to a full presidential mandate. Politically, the Trade Federation seeks to subdue Naboo to secure its commercial routes, so Palpatine –Darth Sidious, playing 3-D chess on a galactic board and covertly commanding both sides– prods Queen Padmé Amidala to expose the war's horrors and move a vote of no confidence in Valorum (effectively forcing a prime minister to resign). Thus our true protagonist, Palpatine, assumes power as Chancellor.

The Republic’s Drift Toward Federation

A constitution isn't just that handy blue booklet you might keep at home. Often what that booklet describes doesn't map cleanly onto objective reality. A constitution is, at bottom, a society's political organization –its form of government– whose written codification is called "fundamental law" in the nineteenth-century idiom. We routinely confuse political form with its written script.

Back to Dicey: with the United States split between Republicans and Democrats, the Electoral College functions less like a council of national sages and more like a partisan, federalized upper chamber choosing the President. The written charter is elegant; applying it to a changing society is something else. Dicey can see this clearly because he's English: the UK's order is grounded less in a single codified text than in the organic development of power and its piecemeal codifications.

What distinguishes a federation from a confederation? Among other things, a lower house that sits alongside the Senate –an institutional acknowledgment that the constituent units also belong to a broader national people. Even if we live far apart with different customs, we're the same polity. Residents of Buenos Aires Province and Río Negro alike are Argentine: the former send many deputies (democratic principle) while both send the same number of senators (federal principle). This is a step up in centralization: the units' will is constrained –and expressed– by the population's will; more populous units carry more weight.

On national identity grounds, forging a cross-species federation is practically impossible. Yes, Star Trek imagines one, but that is closer to a confederation –a union that acts collectively while preserving deep separations of identity. A shared national body across different species, cultures, biologies, and light-years is a stretch.

When the Clone Wars break out, Palpatine pulls the levers from Coruscant. The Trade Federation launches terrorist strikes with droids and mercenaries; corporate allies pile in –the Techno Union, the InterGalactic Banking Clan– under Darth Tyranus (former Jedi Count Dooku). The Confederacy of Independent Systems (CIS) fields a centralized army of battle droids. Sovereignty, at its core, is the monopoly of legitimate force: violence inward, defense outward. The confederal Republic lacks that: each unit could put its token into the war effort, but there is no binding common authority to compel it.

Naboo's Gungans and humans threw themselves into the fight when invaded, because their own sovereignty was on the line. The Republic, by contrast, waits on Jedi envoys to broker peace –never a sure bet, since the Jedi are a religious order with their own agenda. Droids and clones close the circle precisely because they're treated as less than persons –cannon fodder. With droids, it's obvious: in Star Wars, robots occupy an enslaved role.

Palpatine maneuvers to obtain emergency powers after a rousing speech by "super-senator" Jar Jar Binks, formally authorizing the Grand Army of the Republic. More and more state functions slide under this military umbrella while hard-liners consolidate authority. Not to worry, Palpatine assures the Senate: once the war ends, he'll dissolve the army and step down. Or so he says.

From Presidentialism to Empire

By this point, a lower house isn't even necessary to mark the constitutional change: the Republic has become an effectively centralized state. It would have remained a confederation if each planetary system had raised its own troops and fought the CIS in concert-rather than commission a human factory to mass-produce soldiers destined to die for someone. Perhaps the Republic deserved to die.

Constitutional separation of powers normally keeps a head of state or government –prime minister, chancellor, president, even king–from smashing the laws at will. That's absent a declared state of exception. Here, boring but precise Dicey gives way to the more controversial Carl Schmitt. In Weimar's crisis, Schmitt argued that the Reich President should govern through plebiscite and, if needed, deploy constitutional emergency powers to crush corporate (guild, business) and ideological (religious, party) interests that threaten the state's neutral unity –thereby asserting himself as sovereign.

After the Jedi fail to arrest –indeed try to kill– Palpatine, having discovered he was Darth Sidious all along, the Chancellor walks into the Senate with all he needs: the Jedi's "treason", their swift extermination (Order 66), and the final destruction of the CIS. He proclaims an Empire. "So this is how liberty dies… with thunderous applause." He does not dissolve the Senate –not yet. That comes in Episode IV, nearly two decades later.

Functionally, the polity has shifted to Empire: military legions and their industrial-intelligence complex become the ultimate decision-makers in public life. For Hobbes and Schmitt, sovereignty is the final decision. In a democratic republic we try to split that decision across institutions reachable –at least in theory– by ordinary citizens through suffrage. Sovereignty is pushed to the background by constant democratic exercise. Empire brings it roaring back to the foreground.

The Surrender of Democracy

My favorite prequel moment is Mace Windu killing Jango Fett. It may seem out of context: a lightsaber duel, a clean decapitation, Dooku's startled look, and Boba –Jango's son– scarred for life. It matters because you don't expect a "knight of cosmic justice" –which is what the Jedi are, in theory– to decapitate anyone. Yes, in a fight to the death Windu is forced by circumstance. Yet the film lingers: Dooku's surprise at the brutality; Windu glancing down as if asking himself, did I really just do that?

The prequels show the fall of the Republic –and the fall of the Jedi Order. They chase a prophecy; they try to play politics without admitting they're playing politics. They accept the clone army but won't confront the state of exception; they accept Anakin as Palpatine's bodyguard –but only to spy on him. Between palace intrigue and doctrine they lose the thread. By their own orthodoxy they know Anakin is too old and unstable to train –yet, what if the prophecy? They claim not to interfere in the Republic's internal politics, but even choosing not to intervene is still a choice.

And the Senate? They prove Palpatine's critique: too timid to rouse their own worlds to arms –either to repel separatists or protect neighbors– they commission an army of vat-grown humans and ask the Chancellor to take charge. In a dark bit of wisdom, George Lucas once said: democracies aren't seized by tyrants so much as they let themselves die. They surrender because they fail to care for themselves –because representatives forget, to paraphrase Stannis Baratheon, that the point isn't to win office in order to save the republic; it's to save the republic so as to be worthy of office. It's a daily duty whose only reward is the republic's fragile health. When people feel betrayed, they start wondering whether to gamble on an order that no longer rests on them. Maybe the dark side. Or the heavens.

EN

EN