In issue No. 20 of Lazer magazine, Leandro Oberto published a long piece on the highs and lows of Fantabaires 2000, a pop-culture event billed as "the biggest in South America". There, the magazine's director –and one of the most important figures in the fandom at the time– singled out "the kids in costume" as the best thing about Fantabaires: "the clearest sign of a generational shift", he wrote. Something was about to happen. Something was on its way.

In that hinge period of the early 2000s, "nerd" was starting to swing toward "cool", and American comics had little choice but to bow to the force of the Japanese wave. Inside that tangle that was brewing, "the kids in costume" became the figurehead of a shift in the scene: goodbye solemnity, hello laughter.

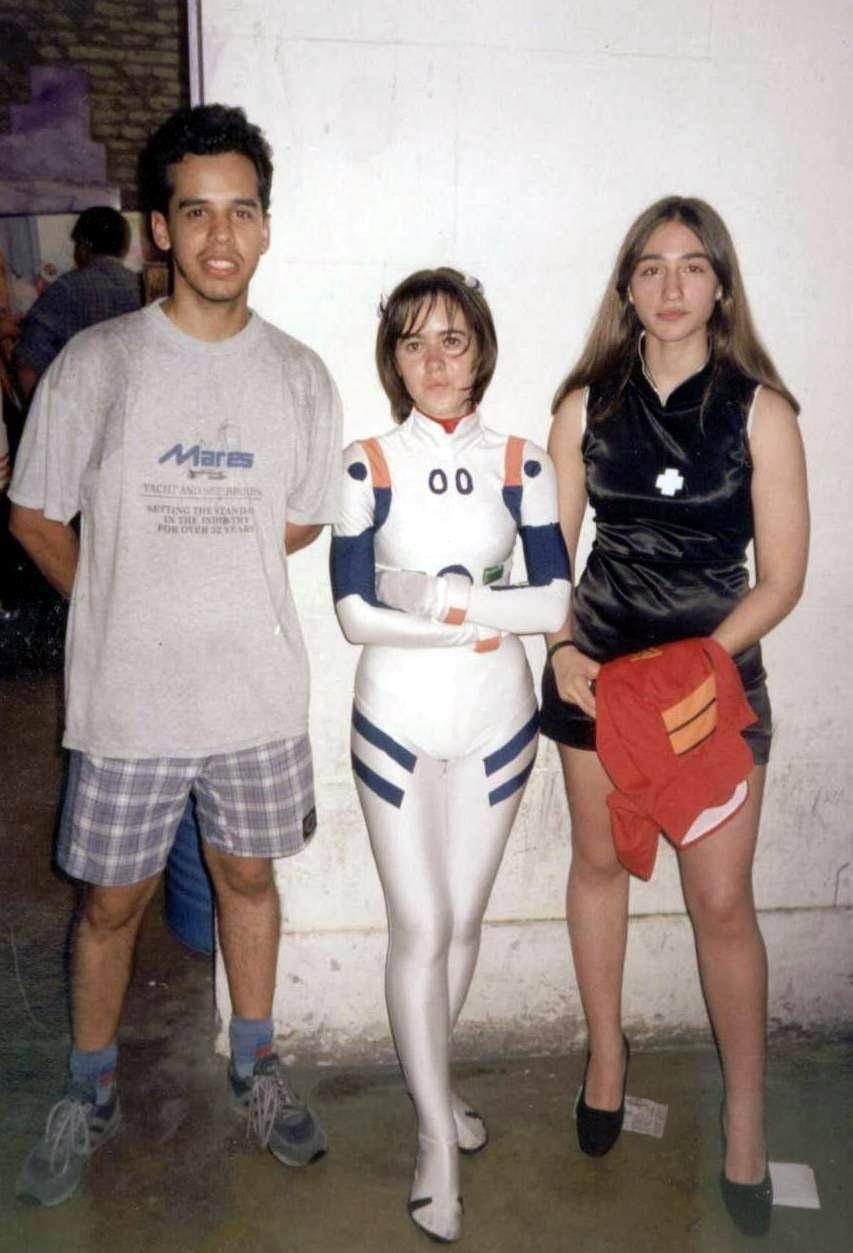

"I don't know of any convention in the West that has a costume contest", wrote a young, sharp-tongued Oberto in that Lazer issue with a Sakura Card Captor cover, paired with an unforgettable cover line: "Fantabaires Contests: 17 Pages With Every Image and Moment From the Controversial Convention". Off to the side, an image of the mythical Rei Ayanami: María Dolores Merlo, an icon of that Fantabaires –someone few of us know much about, but many of us would love to. It still wasn't "cosplay", not yet. But even with all its informality –riding a youth supernova–Fantabaires' "costume contest" was, without a doubt, the first cosplay contest in the country.

"People took photos with the costumed kids, asked them to sign autographs… it was incredible. They were undoubtedly the strong point of the convention. Boys and girls, you deserve all the credit for saving Fantabaires", Oberto wrote in his long chronicle. The spark caught after a first run on Saturday, December 9, 2000. When word of mouth spread, they did it again the following Saturday –but things got out of hand: some 180 participants and 3,000 spectators packed into a room set up for 1,000.

And once that machine switched on, it never stopped. Costumes, crowds, youthful effervescence. As often happens, the protagonists aren't fully aware they're making history –history makes its way as you go. Today, Oberto is a prominent publishing entrepreneur who commands a major share of the Spanish-language manga market through his work at Ivrea, the publisher that brings out some of the most important Japanese IPs. Many of those early-era cosplayers are still tied to the fandom; others –like the mysterious María Dolores Merlo– went their separate ways.

Twenty-five years and a few days after that initiatory milestone, Oberto remembers it as an event full of "energy and chaos". Speaking exclusively to 421, the Lazer boss says: "Back then, conventions revolved mostly around American comics, and the organizers knew little to nothing about manga. We read U.S. comics and local comics too, but we knew manga inside out –and we wanted Argentina, in that sense, to someday look like other countries. So we kept pushing the organizers to let us put together a cosplay contest and do it with a certain sense of humor, like the one we had in the magazine. But they gave us little to no logistical or organizational support –no real crowd-management help. Things became hard to handle. And chaos reigned".

Twenty-five years ago, the cosplay scene didn't exist –at least not in anything like today's professional, established, mainstream form. It all started, Oberto recalls, with "some people showing up in costume at the Fantabaires comic conventions". Maybe 20 fans at most, throwing themselves into the adventure of making their own outfits, masks, and accessories. After all, cosplay is short for "costume play", something you could translate as "role-play in costume".

From that Fantabaires 2000 contest on, the scene evolved fast, until it began to resemble what you'd see in other parts of the world. "We went from simply dressing up to doing cosplay, which is more complex", Oberto says. And in that crew that sensed something powerful was brewing was Agustín Gómez Sanz, then an associate editor at Lazer.

Gómez Sanz also spoke with 421: "In all the previous years, when we covered events for Lazer, we always highlighted the best costumes and the funniest, most creative stuff from the people who came by our stand to say hi. That's where the idea came from: we suggested to the organizers that they should just run an actual contest –and we offered to host it ourselves". It's kind of wild, but back then Lazer's writers were like rockstars in Argentina's homegrown anime cosmos.

The idea was for those rockstars to interact with "the kids in costume", and for the audience to join in too. With real foresight, Team Lazer knew how to capitalize on that tailwind. "It was simply a way to recognize the work people put into their costumes. We made up the categories on the spot –we didn't think of it as anything more complex than having fun together and celebrating their dedication", Gómez Sanz says.

Packed tents, fear of losing control, a sea of kids in a hormonal maelstrom, barricades with police in front of the stage. "Neither Leandro nor I had any idea it was going to get that massive. Everything was new back then, us included. It had barely been a year since our first manga releases!", Gómez Sanz continues.

Despite his fond memories, you can still sense the testosterone spike every time a girl walked onstage in costume. Different times, different story. "I'll say this: that same crowd cheered like it was a goal whenever little kids came up with their parents. You could see the joy of recognition on their faces. It was a surreal experience", adds the now-Ivrea translator.

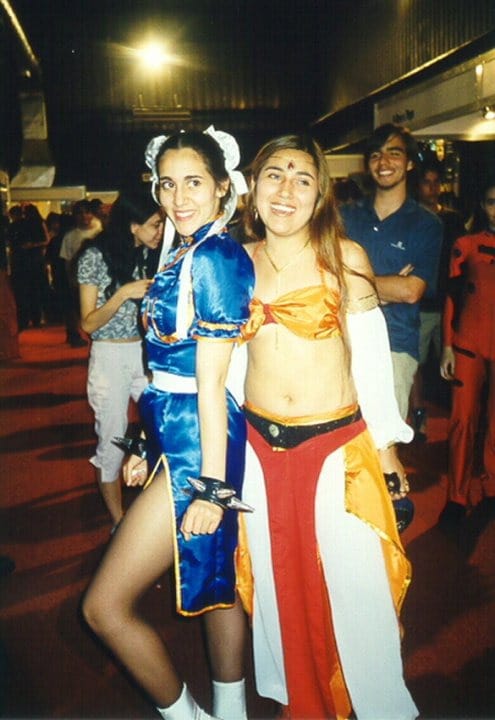

Among the women remembered from that era is Vichun –Victoria Ruiz Menna– popularly known as "the Argentine Chun-Li". Asked by 421, she recalls that "being a cosplayer back then was really weird". Why? "Because the word cosplay came later. Back then we were just 'the costumed kids'. At Fantabaires '99, if you showed up in costume, you got in for free. And we were the weirdest of the weird. But kids would grab the event booklet and use the back –where artists were supposed to sign autographs– to ask us for signatures. It was this mix of bravery and novelty", says Vichun, who's currently working on a PhD in biotechnology and still has a soft spot for Chun-Li.

Fabrics, scraps, cardboard, macramé –whatever worked. Grandmothers and moms helping with cuts, darning, makeup, wigs. Dressmakers hand-sewing strange little outfits. A real DIY aura in the air. In Vichun's case, she designed her Street Fighter costume with her mother. "I thank her for burning her eyes out with me that night", she says. Vichun ended up at the costume contest thanks to Lazer and the Fantabaires 2000 ads she kept seeing everywhere –ads that promised the appearance of actor Lou Ferrigno, the Hulk from the TV series, who never made it to Buenos Aires. In the end, it was the kids in costume who, as Oberto put it, "saved Fantabaires".

That day, Vichun realized "everything came down to the visual", and that you had to be brave to step onto that stage: cans or batteries could fly; you could hear crude catcalls; you might even catch the worst things anyone could say out loud. Still, her Chun-Li (from Street Fighter Alpha) was received warmly. So was the Asuka from Neon Genesis Evangelion portrayed by Cynthia Anahí Platas Puente, now a graphic designer and illustrator. "We were the weird ones", Platas Puente reiterates. For those kids, it was an innocent adventure –a place to share tastes, information, friendship.

"When you saw cosplays, you'd ask how they were made. It was pure fun and laughter –and an excuse to meet cool people to hang out with. The rest of the world looked at you and didn't understand a thing", adds this homegrown Asuka. The reception to her Asuka in a plug suit was insane: suddenly half the convention wanted photos and autographs. That innocence and fantasy also came from how hard it was to separate the character from the person. "It was funny: some people couldn't separate me from the character. And that was the only time I've ever been applauded in my life."

The crowd was chaotic and adolescent –sometimes sweet, sometimes out of pocket. A tough jury that, according to the chronicles of the time, couldn't pick a winner. The hot potato got passed to the organizers, specifically to a woman named "Carla". No one was crowned across those two nights of uproar.

Still, that early fandom smoothed the road for everything that came after. "I feel a bit like a pioneer", Vichun says. And she is. Those kids opened a path and invited fans to come out of the otaku closet: to leave behind shame/shyness/fear around liking anime –and flip it into a kind of galloping pride. "Today you've got a whole market one click away. Back then you had to dig, search, go to Barrio Chino, hit video stores, track down a VHS copied fifty times. There was something very communal –more physical", Vichun remembers.

And so the movement expanded: changing interests, drifting toward new points of contact, setting new goals, mutating some of its original DNA. Meanwhile, David el Saxofonista –one of the most important researchers of Argentina's fandom– claims that "cosplay is like a mirror of Argentine culture".

He elaborates: "From Fantabaires to the most recent presidential elections, you can see cosplay as a total witness of shifting eras. The distance is insane –from the early bootstrapped beginnings to the kid who walked into the voting booth in December 2023 dressed as Chainsaw Man. I feel like the old essence –just looking for fun– has been forgotten, and a lot of people now crave protagonism that turns into fierce competition. That's why you have to look for the classic values in the boys and girls who are just having fun with their outfits –those who pop up, for example, in the Japanese Garden or at some event. The soul of that universe should always live in childhood, the seed of everything".

Beyond the visible rise in overall cosplay quality, the old protagonists see today's scene as "a bit boring". Platas Puente adds: "I see it as a business. A lot of people have fun, but others chase their moment of fame –exposure– feeling like they're someone. Very influencer. I feel like we lost that naive thing that gave the event its magic. Today, a lot of suits and wigs are bought. Cosplay used to be something you'd figure out how to make yourself. It was an art in itself".

Stirring the pot of contemporary references, Vichun adds that beyond pure talent, things changed because "cosplayers get respected when they have a lot of followers". Still, she admits the scene "reached another level –real recognition– where cosplayers try to convince you that you just stepped out of a video game, a movie, an anime, a manga. There's a lot of work behind it".

From there, a new question takes off: did professionalization grow the scene –or cool it down? "It's a double-edged sword", Vichun says. Reach increased, but freshness took a hit. "Sometimes people who are just starting out are afraid to compete with someone who's been at it for longer. The point is not to think of cosplay as competitive, but as something that should give you satisfaction. I'd like the scene to create opportunities for newcomers, so they don't feel isolated. That's something organizers have to work on."

Platas Puente agrees: "I'm not saying it's better or worse –some people just don't have fun the way we did. The whole process: making it, laughing at yourself, drinking mate with friends while you sew. Now you press a button, the costume arrives from abroad, you try it on, do your makeup, and that's it. Before it was more fun and more naive. Today some people think they're stars. Before, you'd sit down with a Dragon Ball character, a Saint Seiya Knight, or a Sakura to drink mate. It doesn't happen as much now".

Gómez Sanz felt that shift firsthand years after Fantabaires 2000, when he hosted another event in the same orbit. He came in with the same old energy: complicity, interaction, laughs. He got shut down immediately: "'Don't make jokes or comments about their costumes –everyone here already has a routine prepared,' they told me. I wanted to bury myself alive". Still, he finds it "sensational" that "something so niche is celebrated", and he celebrates the fact that "the fear of being ridiculed is gone".

In the end, the Fantabaires 2000 crew converges on the core of the old question. "Deep down, beyond prizes, it's worth celebrating the creativity and dedication behind each cosplay. At some conventions I suggested awards for shoestring and janky cosplays –forcing ingenuity, but also acknowledging that we're all putting cut-up flip-flops on our heads and pretending we're aliens", Gómez Sanz says.

Today, cosplay events and contests enjoy popularity and respect. The scene grew, new reference points emerged, and brand-new ways of consuming and making cosplay took shape. There are prizes and celebrities. We even have a cosplayer who became a National Deputy. Cosplay quality is through the roof, and the whole thing is genuinely mind-blowing. What began as a party full of hacks, improvisation, and yelling became a highly professional scene chasing perfection –and aiming to embody fictional characters as convincingly as possible.

"In my view, both realities are socially interesting, and neither is necessarily better than the other. Maybe the only issue is that so much professionalism pushed the fun part into the background –and today there are fewer places to take things less seriously and do it just for the joy of it", Oberto concludes, one of the scene's founding fathers. Luckily, nobody's in the closet anymore. But extreme professionalization ended up shoving that old territory we used to call "fun with friends" back into the wardrobe –doing it just to mess around, to bust chops, and call it a day.