Gaming feels stagnant. The vast majority of blockbusters (so-called AAA titles) seem trapped in big-budget production cycles, repeating safe formulas, and technical ambitions that outweigh storytelling. Add to that the very high prices for games we're unlikely to finish –or even to play for more than 30 hours.

Faced with this panorama, the independent scene kept gaining ground. In the last fifteen years, the indie scene didn't just offer different, original and more accessible experiences economically. It also allowed the return of a figure that had been overshadowed because of "the industry" (except for some special cases, such as that of Hideo Kokima): that of author. Something reminiscent of the early days of the medium, when names like Ron Gilbert or Tim Schafer were recognizable behind a title –like a film director behind a movie. Distinct authorial signatures, such as those of Chris Sawyer with RollerCoaster Tycoon.

We can trace this new indie wave back to 2008, led by Jonathan Blow's Braid, followed by Markus "Notch" Persson's Minecraft (2011) and Team Meat's Super Meat Boy (2010). But this piece is dedicated to someone who appeared a little later, in 2013: Davey Wreden. A creator who turns his works into spaces for philosophical and psychological exploration. Which uses interactivity not to entertain in the classical sense, but to confront the player with uncomfortable questions about freedom, creation or identity. As I like to say: multi-layered art.

The Stanley Parable: Our Very Own Cave

In 2008, a young Davey Wreden –a 22-year-old Nintendo fan and film student– decided to learn how to use Valve's Source engine. He had an idea: give the player the chance to disobey the narrative imposed by the game and explore the consequences. Thus was born his first masterpiece, The Stanley Parable, which in its first version was a Half-Life 2 mod and only received its standalone release in 2013.

The allegory of the cave it is the most famous in the history of philosophy. In it, Plato describes how a group of people live chained in darkness, believing the shadows they see are reality, when in fact they are being projected by other humans who control them. Discovering the truth and escaping from that cave does not guarantee happiness: on the contrary, it usually brings rejection, misery and even death to those who try to free others.

Many modern works took this metaphor, such as Matrix or The Truman Show. But The Stanley Parable is different, because here we are the ones who decide if we escape from the cave. Control is in our hands, something that only the format of the videogame can give us.

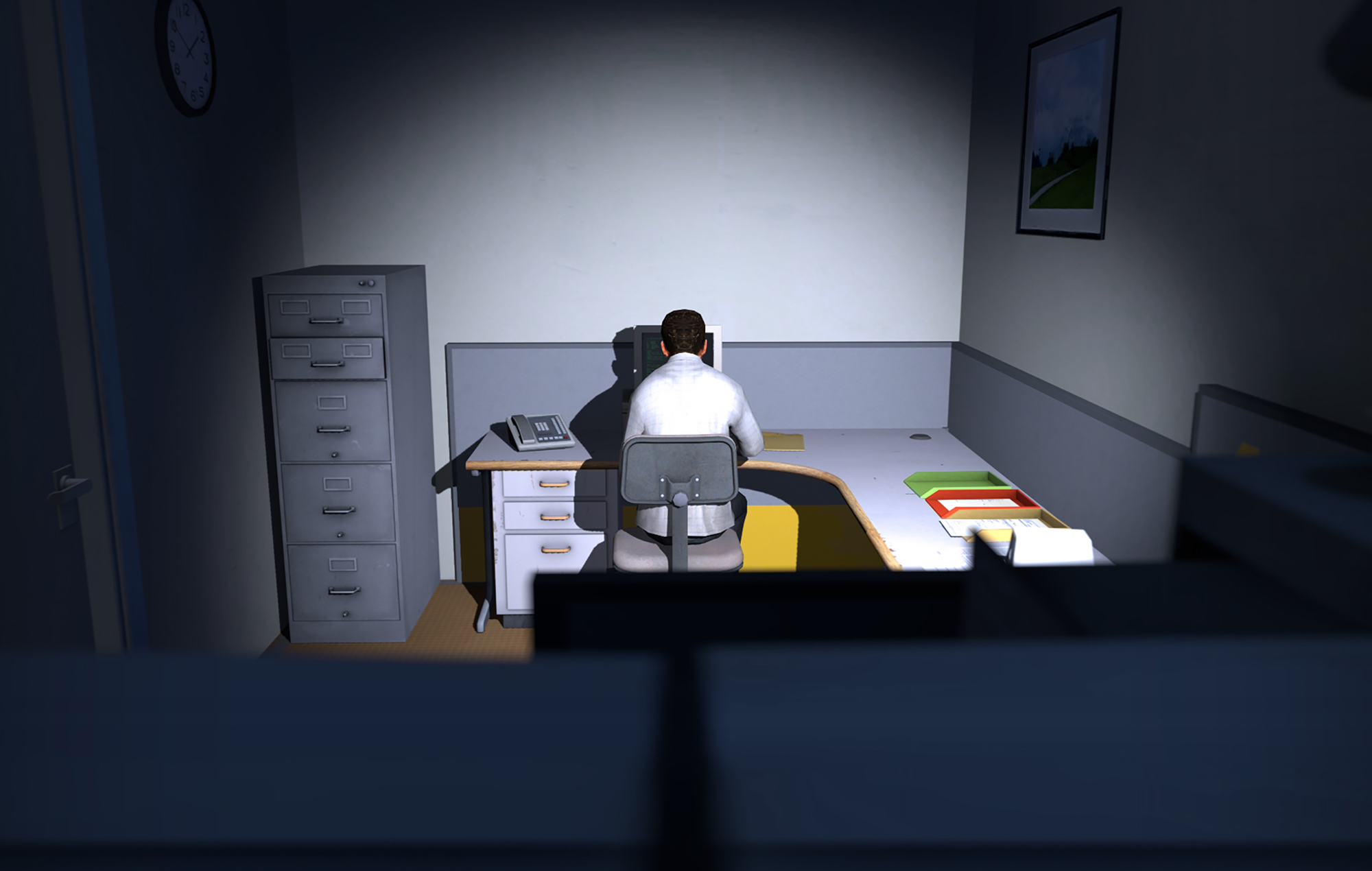

"Stanley worked in a large building where he was employee 427. His job was to press buttons on a keyboard – the buttons he was told to press, and for how long. To anyone it would seem like a boring and exhausting job, but Stanley enjoyed every moment the instructions appeared. He believed he had been created exactly for that, he was happy.

And so one day, something very peculiar happened... After sitting in front of the monitor for an hour, he realized that no instruccion had come for him to continue. This had never happened, something was clearly wrong. Shocked, frozen, Stanley found himself unable to move for a long time. But when he came to his senses , he rose from his seat and headed out of his office..."

(If any of this reminds you of Apple TV+ series Severance, it is because the game was its source of inspiration, fact confirmed by its creator)

This is how we are introduced to the story of Stanley, which from there also becomes ours, since we take control of this obedient worker to help him escape from his routine and finally be free. Or is that what the narrator wants?

Because, of course, if we pay attention to everything this omniscient voice tells us we will be able to reach a happy ending, the curious fact that it's the game's only happy ending –and this is important. Stanley discovers the company's malevolent plans, turns off the machinery and manages to escape: get out of the cave and be free. All of this happens by following every instruction to the letter as we progress.

... No one would ever tell him where to go, what to do, or how to feel again. Whatever life he lived would be his.

And that was all he needed to know. It was, perhaps, the only thing worth knowing.

This was exactly how everything was meant to happen. And Stanley was happy.

But the game restarts and we return to Stanley's office, and as we move forward and hear the same words again we realize that everything has started again. The ending was happy, but it wasn't satisfying. What had happened to his companions? Why, beyond Stanley ending well, don't we feel free? Something feels weird. The problem was that we had done everything we had been told. Freedom felt illusory, and it was.

So we begin to explore other options, to challenge the narrator, to go through the door on the right when he specifically tells us to go through the one on the left. We become the owners of the story, because Stanley would never have done that, his script was already written and ended in freedom, a false freedom. He was still chained in the cave, we really wanted to escape.

In fact, this idea delves into one of the most particular endings, which begins when Stanley walks down a dark corridor with an "ESCAPE" sign. Without going into too much detail, Stanley dies and the player arrives at a game museum. It is the only moment in which the narrator switches to a woman's voice, who says: "When every path you can walk was pre-built for you, death becomes insignificant. Do you see clearly now how Stanley was dead from the moment he clicked Start?"

Thus, we will fight tirelessly against the narrator and his game, which consists of a large number of variables and no fewer than 19 endings (or maybe more?). Some are interesting, some are funny, some are strange. But none is "happy" like the first. Because what The Stanley Parable puts at the center is not simply the choice between doors or paths, but the most uncomfortable question: Does free will really exist in a world where all options have already been designed?.

The Beginner's Guide: After the Fame

After the explosive success of his first work –even having a cameo in Netflix's House of Cards–, Davey Wreden entered a depression marked by the tsunami of attention that crashed over him. The story of the human being who becomes famous too quickly, and the consequences that this brings, is a story as real as it is known. The interesting thing is how this author, already acclaimed as a game developer, decided to get ahead after hitting rock bottom. Thus was born his second masterpiece: The Beginner's Guide.

Moving away from satire, this more intimate and personal work manages to give closure to the first chapter of an outstanding artist, because in a certain way it works as a spiritual sequel to The Stanley Parable. Not because of the themes it touches on, but because of its structure, the idea of a narrator, the visual resemblance and the oppressive atmosphere.

Although here Wreden breaks the fourth wall from the beginning:

"Hello, thank you very much for playing The Beginner's Guide. My name is Davey Wreden and I wrote The Stanley Parable. While that game tells a slightly absurd story, today I'm going to tell you about a series of events that happened between 2008 and 2011. Let's review the games made by a friend of mine named Coda..."

This is how he walks us around a beautiful collection of short or unfinished videogames, starting with an experimental level of Counter-Strike. He tells us that he created this project in the hope of showing Coda's art and thus being able to motivate him to create games again.

While we explore and play the prototypes, he explains his interpretation of every detail: the objects, the textures, the maps that end abruptly. Each explanation seems to make sense of what we are playing. But what appears to be an act of kindness keeps getting darker. Why are you so obsessed with your friend's games? Is everything you explain really like this? Will Coda want its games shown? Is Wreden appropriating them? These questions and many more are what the game raises, as it explores the conflicts in the triangle between artist, viewer and work.

The line between the real Davey Wreden and the fictional one remains diffuse for the hour and a half duration. And, thanks to an extraordinary vocal performance, it gives us one of the most memorable endings in the history of independent games.

Long Live Authors

I celebrate Davey Wreden. His games do not need photorealistic graphics or complex mechanics to be revolutionary. Instead, they manage to make the most of what distinguishes the videogame from any other medium: the ability to involve the players, to make them an active part of the work and confront them with questions that accompany them far beyond the screen. This is interactivity as its own artistic language.

Thanks to his story, and even seeing local examples in Argentina such as the case of LCB Studios, I can't help but feel hope for the future of videogames as a medium where great creative minds can express themselves without needing big-budget tech and, with pure imagination, shape works capable of leaving their mark on culture.