This text might look like a game review, but it feels more useful to talk about the phenomenon El 39 belongs to: meme games. It’s a newly coined label, sure –but it helps explain what’s been happening on social media lately: the hype generated by game trailers that we never end up playing.

El 39 is a video game by Bohemian Productions (Lucas Gomila and Ramiro Argente), a very, very small studio. As they note at the end, they built it from scratch –no budget, no backing– purely for the love of it. And that’s how El 39 should be read: not against other indies or AAA titles, because that comparison would be unfair.

El 39 puts you in the shoes of a protagonist who’s just left a party in Constitución and needs to catch the bus back to Chacarita. But –oh, coincidence– he misses it and ends up totally exposed at 3 a.m. on the streets of “Constitown”. To make things worse, his phone gets stolen, so he has no choice but to walk home. He asks for help at a nearby Ugis pizzeria, where the guy behind the counter tells him about an underground network of tunnels that could take him back to his neighborhood. That’s basically what the game is. Strictly speaking, it’s closer to a long demo (it would probably benefit from being priced at $0.99 USD).

Whenever I play a video game, I try to pin down two fundamental aspects: its mechanics (the basic actions you can perform) and its world –the virtual space the game builds, where those mechanics make sense. On that axis, El 39 is almost 90% world. Its best feature is how it builds small, contained spaces that are still enough to generate atmosphere. A game without atmosphere is usually doomed: it can’t achieve any immersive effect unless the mechanics are flawless. And mechanically, that’s where El 39 is weakest: you mostly walk around, interact in very basic ways with a few objects, and solve a handful of simple puzzles.

Still, this isn’t really a complaint –because we’re back to the starting point. This is a game made by friends with no money, no institutional support, and no ambition beyond finishing something fun and personal. Anyone who’s even vaguely familiar with game development knows how quickly “better mechanics” turns into a budget and time sink that can sink the entire project. In that sense, El 39’s balance between ambition and actually shipping the thing makes perfect sense.

That said –and this is surely something the team has thought about– adding combat, an inventory system, and more areas could quickly turn El 39 into a low-budget, Buenos Aires flavored Resident Evil. Not that low-budget, though: building those systems would almost certainly require external funding from a publisher or a grant. Which brings us to the real topic here.

Meme games

El 39’s entry into the public conversation was driven by two forces. First: the 2024 low-poly / PS1-style trend, where people started 3D-modeling everyday objects as if they belonged in a PlayStation 1 game. That meme quickly mutated into modeling Argentine objects and places, and it went viral in the way only the current internet can manage. Shortly after that wave peaked, a trailer for El 39 appeared: it didn’t just use that aesthetic, it turned it into the skeleton of what looked like a real video game. A bus. A street in Constitución. An Ugis. That’s enough to give the trend a distinctly Buenos Aires spin.

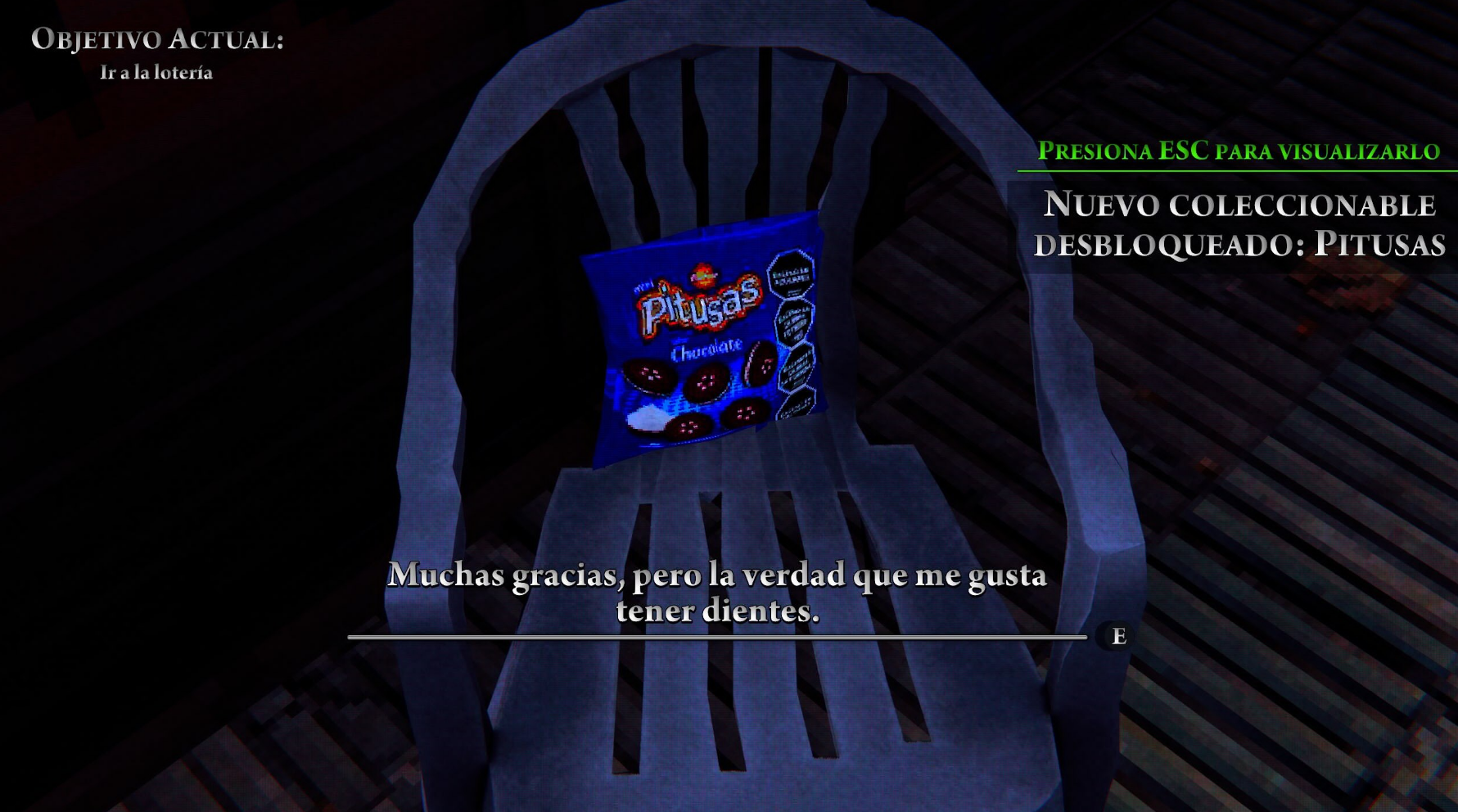

El 39 also packs in a battery of memetic references –Argentine internet slang and in-jokes– inside the game itself. In other words: it’s a memetic construction that also carries other memes. A memeplex, basically. Point in favor.

Second: the Argentine audience’s ongoing impulse to ask for local games, series, and films where Argentine identity is visible on screen. That question has been floating around for decades –ever since the consumption of U.S. pop culture (and the transformation of its products into aspirational fantasies) started turning into a question about the local. Why can’t we do this with an Argentine lens? Why isn’t there a strategy game about the wars of independence? Why not a post-apocalyptic FPS set in Buenos Aires? Why not a game about the Falklands/Malvinas war? Why don’t we have a proper “gauchos vs. lobizones” game? In that sense, El 39 is a partial answer to a very specific version of the question: why don’t we have a survival horror game set in Constitución?

That hunger for self-representation is part of what turned Okupas and Los Simuladores into pillars of the Millennial canon, and what made El Eternauta (Netflix) feel like an update of that shared imaginary. Watching the series, I genuinely got excited when I spotted an ad for Blem –that’s where we’re at. That’s the level of detail that now reads as “culture”, as “home”, as “us”. And yes: that desire also extends to video games.

But the desire has also started producing its own backlash. I recently saw a widely shared tweet asking, “Why do all Argentine video games have mate and capybaras?” –as if the only way to make an Argentine game is to pile up symbols of “Argentine-ness”. It’s a valid question, but it also seems to ignore what the local industry actually looks like today. Think of Nimble Giant, Tlön, LCB Studios, and Storyteller: games and companies that have found different levels of success with IPs that don’t lean on Argentina as a gimmick. Beyond that, I think it’s healthy that the public is even debating what an “Argentine video game” is –because, in the end, it’s the public that’s going to support these projects.

And finally, there’s one more thing that defines this meme-game ecosystem: a lot of these demos –or these “meme games”– only exist as trailers. They never reach a demo, let alone a complete game. There are many reasons for that, but the core one is simple: a viral clip isn’t enough to secure funding or publisher interest. Another is that, as with Bohemian Productions, these projects often come from tiny teams with no money, and they never manage to move beyond the trailer stage.

That’s why, in an ecosystem full of hype –trailers that never become games, and concepts that never stop being wishful thinking (like “why isn’t there a Red Dead Redemption 2 about the Conquest of the Desert?”)– the fact that El 39 actually made it to the finish line is an achievement in itself.

And I hope they turn it into the Buenos Aires survival horror we all want.