My first adventure in Elden Ring was unforgettable. I played it the week it came out, without guides or spoilers, on a PlayStation 4 where I didn't even pay for a Plus subscription, so it was a fully offline experience. That run was pretty unique for me: for four months in 2022, the only thing I played was Elden Ring.

At first, every step in the Lands Between feels like the biggest adventure of your life and like you're constantly defusing a bomb. That world that's dead but also very alive, beautiful and horrible at the same time, that lets you relax for a moment but is always testing you, is the creation of a team that's been trying to make that game since the '90s. Those details that blow your mind, especially on a first playthrough, have been carried over and iterated on since FromSoftware's very first title, before the Souls games. That's why Elden Ring is such a masterpiece: because in a way, they've been developing it for 28 years.

King's Field, the First FromSoftware Game

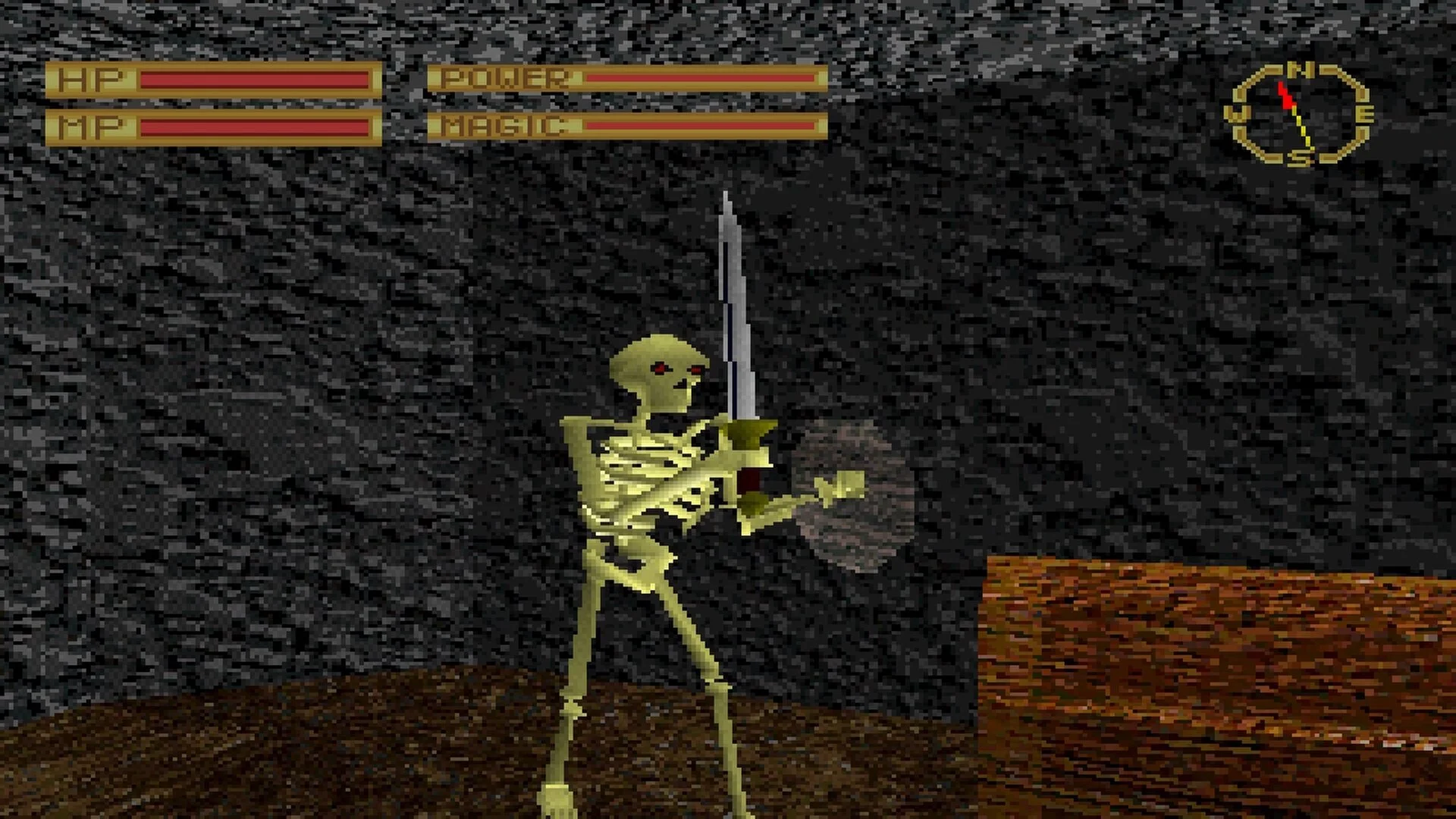

FromSoftware started out as a business software company, even making tools for sectors as far removed from what it does today as livestock and agriculture. When the video game market exploded, the company decided to take a risk and make its first game in order to survive. That's how, in 1994, King's Field was born: the great-grandfather of Elden Ring, directed by the studio's founder, Naotoshi Zin. King's Field was one of the first RPGs on the original PlayStation (PSX), coming out just a few weeks after the console's launch in December '94.

King's Field is a first-person dungeon crawler directly influenced by the "parent game" of Japanese RPGs, Wizardry, but with real-time action. You play as a protagonist who ventures out in search of his explorer father, lost in a dungeon, only to discover that this maze of monsters and traps hides the ruins of a lost civilization. The dark setting, which takes cues from works like Berserk by mangaka Kentaro Miura, created a mood that became part of the company's DNA, including the decision to make their games difficult as a core design pillar.

That difficulty isn't just a matter of cranking up enemy stats; it's about restructuring the whole adventure around the decisions you make, how you manage your resources, and how information –both tutorials and lore– is hidden in the game instead of laid out for you.

Even in that first title there were concepts that would be repeated all the way up to Elden Ring, like using stamina to perform actions: a regenerating but essential resource that adds that particular kind of difficulty fans love. Another detail that was born in this saga and survived until 2022 is the flask concept: the little potion container that gets used up but can be refilled, so iconic in Elden Ring. And without a doubt, another key gameplay element that King's Field shares with later Souls games is the way you save your progress: in crystals that act like the "bonfires" of the Souls series. When you die, that beloved, cursed loop kicks in where you lose your gold and experience.

The King's Field saga had three entries on the original PlayStation and a final one, King's Field IV, on PlayStation 2 in 2001. It even had a later comeback as a mobile game for the Japanese market. In the sequels, certain level design ideas began to crystallize into what we would eventually see in the Souls series. Already by the second game, the world had more NPCs and more distinct locations to visit. And to polish the backtracking –which was slow at first– they worked on better ways to connect the maps.

The idea of blending dungeons together and forcing an almost roguelike loop became one of the core design pillars, carried forward from the first game through all the others, always being tweaked to find a balance where frustration wouldn't completely overwhelm the player.

The Souls Saga: The Rotten Spirit of the RPG

In 2009, a new title from the studio arrived on PlayStation 3, the spiritual successor to King's Field: Demon's Souls. It was Hidetaka Miyazaki's chance to step in as game director, taking over a stalled project. According to the few interviews out there, Miyazaki was a huge King's Field fanboy, but didn't dare to just continue that saga, so instead he took its most important elements and built a new series around them, adapted to the times. The central idea remained the same, but remixed: an extremely dark dungeon and punishing difficulty so that the player's satisfaction would come from overcoming each "unfair" obstacle.

Demon's Souls

In this first entry of the new saga, the perspective shifted to third person, and the team put a ton of effort into the graphics –not just in art direction, but also technically– to keep up with other PS3 titles. It's interesting to see how elements of the user interface start to repeat and persist across the later games with small tweaks: the fonts, the on-screen messages, the inventory and menu layout. Once the studio finds something that works, they keep it and iterate subtly, but the underlying concept stays the same.

If you're a Souls player, you know exactly what the core loop of these games is: that frustrating cycle that makes you feel like a prisoner in a world where death doesn't mean anything anymore and time just repeats and repeats. That loop of checkpoints and death includes a "safe zone" where you can level up and buy gear –something that would return in later games and eventually become the Roundtable Hold in Elden Ring.

When it comes to death, there's something very meta about the design choices made in Demon's Souls and later in Dark Souls. After many hours, you realize that dying is also part of the gameplay, and sometimes the only way to move forward is to sprint, grab what you need, and throw yourself off a cliff. To stop frustration from becoming a reason to quit (while still keeping it as a major filter for players), the "souls" you collect and lose on death can now be recovered –unlike in King's Field, where you lost everything.

This death mechanic also brought along something that would carry over to the rest of the games: bloodstains that show you how other players died, and the ability to invade other worlds to fight them. It's one of the most fun and stressful experiences in the entire saga.

Dark Souls

Dark Souls (2011) is a near-perfect adventure that brings together everything that made the studio's previous games so great. The core concept is deepened in the next three titles, with bonfire checkpoints in the style of Demon's Souls and masterful level design that interconnects the entire dungeon-world. Starting out with a main class –which isn't actually restrictive– and having so many different items creates a huge build system that would fully mature more than a decade later in Elden Ring.

Another central pillar of the saga, starting with the first Dark Souls, is the idea of the Boss, where Miyazaki and his team put a lot of focus. The design of these bosses, both visually and mechanically, is crucial. In Elden Ring, bosses become one of the main pillars of the experience and the game's first major difficulty spikes, with enemies like Margit, the Fell Omen, in Stormveil Castle. I think the decision to make the bosses such strong protagonists, giving them a super-challenging attitude, is what fuels some of our most satisfying memories with FromSoftware's games.

If you've played Dark Souls, we could probably talk for hours about our war stories facing Ornstein and Smough. I think that fight was vital for the game because it set the template for the bosses in later entries.

That said, my greatest frustration in all of FromSoftware's catalog –the one that still haunts me at night– is the Capra Demon in Dark Souls. He's the second "big" boss in the game and I just couldn't stand him. He almost made me rage-quit the whole thing. You know which one I mean: the demon with two dogs in that tiny little courtyard.

Elden Ring, the Souls definitive

With all that accumulated experience and experimentation, FromSoftware released Elden Ring in 2022. It's a visually and narratively stunning game, with massive gameplay depth focused on exploration, character builds, and boss fights where many of the enemies are charismatic enough to be the main characters. Elden Ring not only preserved what was essential and functional in King's Field, Demon's Souls, and Dark Souls, it also incorporated a lot from Sekiro and Bloodborne, two other major titles from the studio that share some concepts with earlier games but place a stronger emphasis on combat.

The experience of Elden Ring is deeply personal, but we all agree the game has some incredible turning points. Unlike other FromSoftware titles, while it's still difficult, it's much more accessible in terms of gameplay. That helped a ton of hyped players jump in and become fans.

I realized just how popular the game had become when, on the Vorterix show Paren la mano, during a chat between Luquitas Rodríguez and Rebord, they started talking about a bug to cheese a boss. The game didn't just break out of its niche; people were talking about it in spaces where Dark Souls had never reached. That, in turn, made a lot of content creators and players go back and try the previous titles.

"Oh, you liked Elden Ring? Why don't you try Dark Souls?" some old guy –like me– will say to a new player.

Elden Ring entered a new phase after the massive Shadow of the Erdtree DLC and with the release of Nightreign, a new multiplayer-focused title. We don't really know where FromSoftware's story goes from here, but looking at how they constantly iterate on their work, fans like us can only hope for yet another return to a dungeon crafted with malice and bad intentions.