Only someone naive could think of fashion or cosmetics as something innocent, I tell myself at first. But sermons and moral maxims are not exactly my field. The truth is that fashion and cosmetics –let me misuse both terms interchangeably– have a peculiar trait: they are everywhere, and therefore manage to hide in plain sight. There is no human being who is not traversed (whether by acceptance, rejection, indifference or intention) by the act of choosing how to dress, even when that choice is largely shaped by geographic, cultural and material constraints. We are condemned to be free, condemned to get dressed. Let me rephrase the well-known line: I already am eating from the trashcan all the time; the name of this trashcan is fashion.

Whether we like it or not, cosmetics are a battlefield. In any bond or relationship in which one is seen by another, choosing an appearance (clothes, accessories, bearing) means taking a position in the world, sending signals about what we like, what spaces we inhabit –in short, about who we are. The famous "Chinese Yankee" of men's fashion, Derek Guy, has written rivers of ink on this; to sum it up, drawing on the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, Derek argues that our clothing signals our forms of belonging and our symbolic capital.

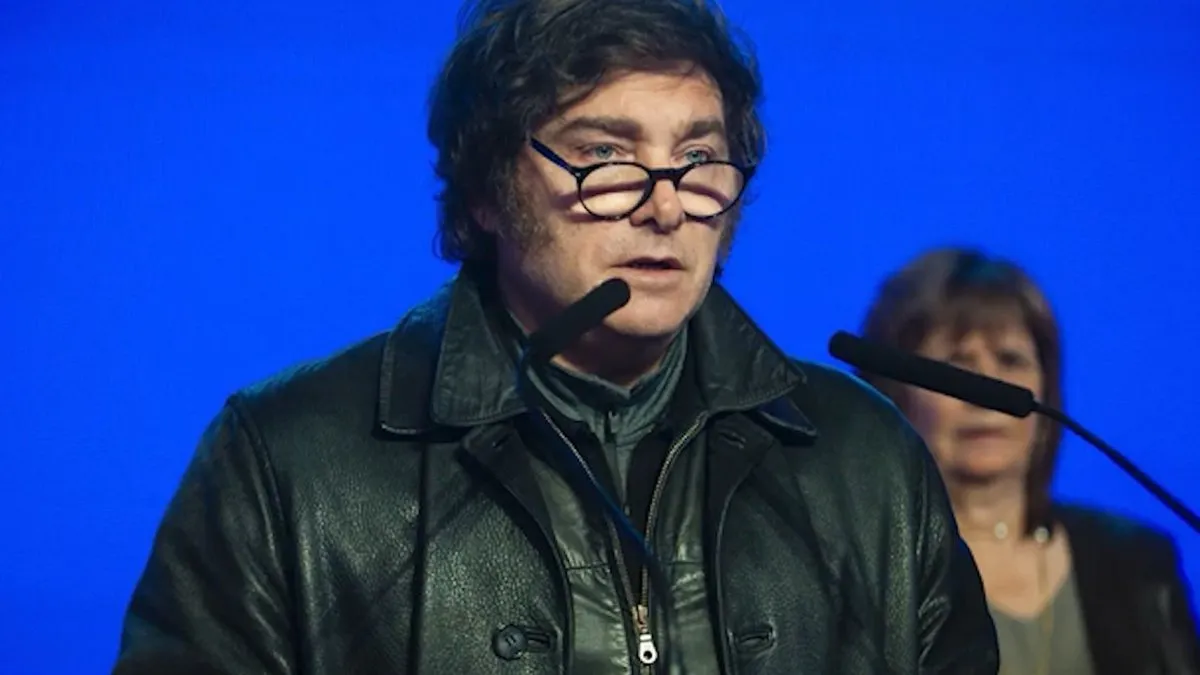

Think of the starter pack of a progressive Peronist leader: the sports jacket and the thermos instantly indicate belonging. They are signs of what one thinks and beacons that call out to others with the same aesthetics to feel summoned. "Politics is war continued by other means", is Michel Foucault's inversion of the military theorist Carl von Clausewitz's famous maxim, and in that Adidas track jacket politics, war and fashion all blend together. Clothes work like the beacons of Gondor, summoning every ally who recognizes themselves in that look, those brands, those cuts or those colors to go into battle. "Uniform" is said in many ways.

Getting dressed is, in that sense, the first cognitive-military operation of the day. You take off your pajamas and you get dressed to face the world. We know this intuitively, even if we don't fully register it. It's there in the English saying "a suit is a man's armor"; in the title of Roxette's hit "Dressed for Success"; in the power suit worn to perfection by Gordon Gekko in Wall Street (1987); in the killer heels of Dressed to Kill (1980). Clothing is a delicate weapon that organizes networks of desire and power, an input for victory for those who have been alerted to its force.

How do they refer in Westeros to those who betray their alliances and loyalties? Turncloaks. What greater humiliation can a military force suffer than the theft of its uniforms, standards and flags, like those captured from the English during the invasions to Argentina of 1806 and 1807.

Fashion –cosmetics– is a field of tensions and representations, of ways of making oneself visible and disputing presence. It's the medium between what we are, what we want to be and what we project; the most basic –and perhaps for that very reason, often forgotten– space of rebellion.

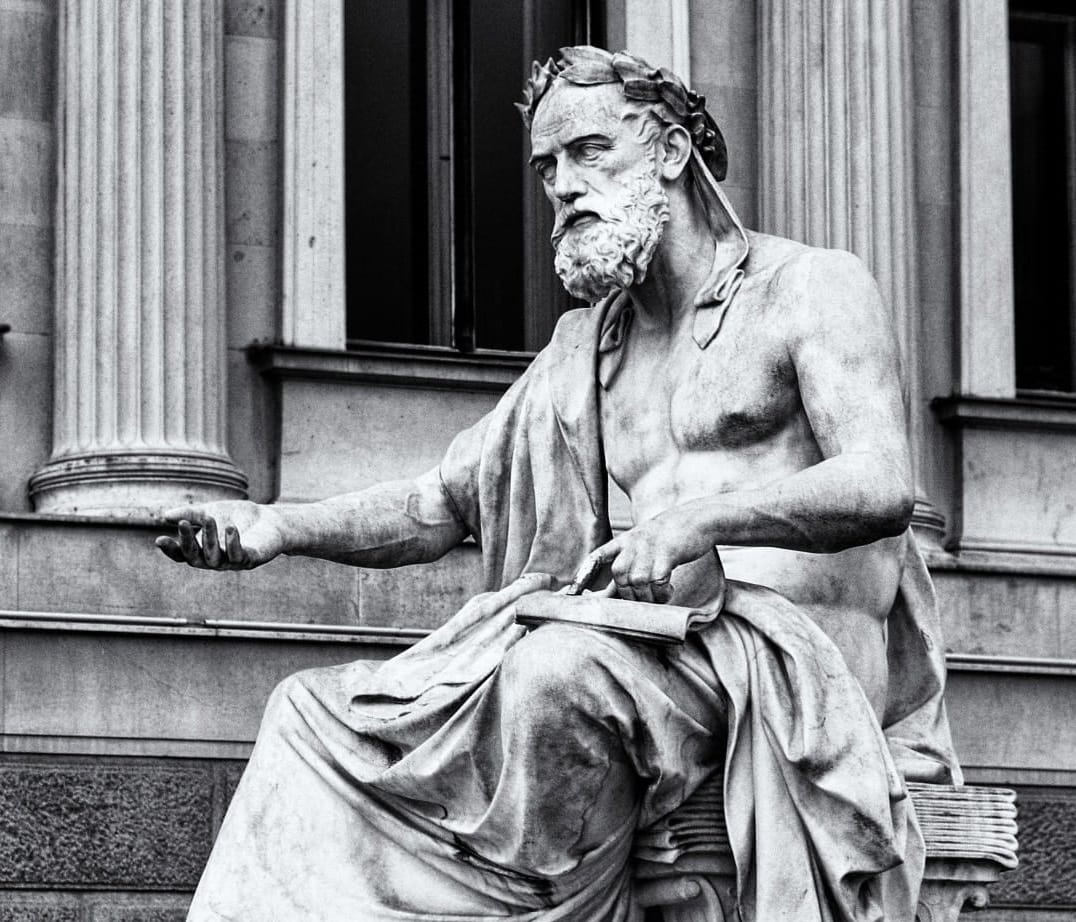

Xenophon: Soldier, Philosopher, Aesthete

The thing is, the ancient Greeks had already thought about all of this, or at least the essentials. So let's go back to Athens in the 4th century BCE, where with Socrates philosophy was born in the way it ought to be lived: as a group of people talking about things while drinking wine. Socrates' most famous disciple and friend was Plato; everyone's heard of him. However, there is another Socratic thinker whose complete works have come down to us: Xenophon. Anyone who has browsed the bookshops on Corrientes Street may have come across his Apology or his Memorabilia (Recollections of Socrates). Or perhaps they've bumped into the Anabasis or Expedition of the Ten Thousand, the book that made him famous and that, the ancients tell us, inspired Alexander the Great to conquer the Persian Empire.

In a nutshell: Xenophon led an expedition of ten thousand Greek mercenaries who, after reaching what is now Baghdad, had to fight their way back, carving a path through enemy territory until they reached the coast of the Black Sea in order to return to Greece. Think about the scale: one hundred thousand armed adult men is the equivalent of a mid-sized city in Classical Greece. An entire city in motion, surrounded by enemies, with the sea as its only escape over 1,500 kilometers away. Xenophon achieved the impossible: in a kind of proto-Dunkirk, he managed to evacuate all those Greeks who, upon reaching the beaches, shouted with goosebumps the famous "Thalatta, thalatta!" ("The sea, the sea!"). After that crowning moment of glory, Xenophon was recognized as one of the great commanders of his time: he was hired by the Spartan king Agesilaus II as a military advisor and, after years of success, retired to a farm given to him by the monarch on Lacedaemonian land. There he devoted himself to writing memoir, history and philosophy.

What interests us here is that this young Athenian cavalryman, educated by Socrates, forged in the heat of battle and tested in the intense political intrigues involving Greeks and Persians, decided to write about cosmetics. A politician, soldier and activist reflecting on fashion: there's a lot of material to cut there –pun very much intended. And the connection is not as strange as it sounds; we see it both on our own national soil and across the Atlantic, in French lands.

A Critique of Fashion: Cosmetics as an Unproductive Lie

Oeconomicus (The Economist) is a work in which Xenophon equates the art of managing a household with that of organizing a society. Everything, ultimately, is politics. The premises, principles and values are the same. The text moves back and forth between the domestic sphere and the public one, underpinned by the core of Xenophon's thinking: pragmatism. In short, whoever knows how to manage a home well also knows how to manage a community well.

Book 10 of the Oeconomicus is known as "the critique of makeup". There Xenophon explores the universe of cosmetics: heels, makeup, dyes and corsets are put in the dock. What begins as a mention of feminine strategies of seduction quickly comes to involve men as well, and cosmetics end up affecting much more than mere physical appearance. Just as eyeliner can enlarge and highlight a woman's eyes, flashy clothes can make people think a man has more money than he really does. Appearances can create illusions that have very concrete consequences in the world.

Is this kind of deception desirable within a couple? Xenophon's answer is no, for several reasons. The first is ethical: there is no way to build a productive life together without a stable foundation of trust. The second is pragmatic: every cosmetic deception is, by definition, temporary. Xenophon offers the oldest gag in the book: after a few drinks, in the darkness of night, makeup and clothes can deceive, but morning always reveals the truth. Maybe not the first morning, maybe not the second, but eventually we all see each other bare-faced.

This focus on the everyday, the emphasis on long-term construction, the attention to closeness and to the things and people with whom one lives and loves, is not trivial. Xenophon is thinking within a society. He is thinking about the household, but we can easily extend the question to the community. Returning to our opening example –the proliferation of sportswear among obviously wealthy political leaders who wear it as if it were a costume– how long can that lie last? How long can makeup, the performance, hold up in a space as intense and intimate as politics? And more pointedly: how durable can a political construction be if it's based solely on cosmetic positions, always doomed to be wiped away?

Elsewhere in his work, Xenophon asks: "What is the best way to pretend to be a good flute-player?" And he quickly answers: "By being a good flute-player". Short and to the point.

A Defense of Fashion: Cosmetics as a Useful Lie

But things aren't that simple. In fact, if Xenophon raises the problem, it's because fashion and cosmetics are especially important for thinking about politics, and there are no easy answers. That's why in the Cyropaedia, the book Xenophon devotes to describing his ideal ruler, there are several direct references to the topic.

Xenophon begins by saying that when he started reflecting on politics, he realized that all governments are destined to fail because human beings, by nature, eventually become dissatisfied. But before sinking into despair, he says he found a single example of a lasting government: Cyrus, founder of the Persian Empire. And so he devotes a long book to telling us everything about Cyrus –how he was educated (his values, his studies and his training), how he conquered his empire and, later, how he governed it. Let's fast-forward to that last part.

Cyrus has conquered more land than he will ever see in his lifetime, roughly the same territories that centuries later Alexander the Great would seize after defeating Darius III. His rule is based on rewards and punishments, strategies of incentive and deterrence, and the careful selection of mid-level officials, in whom loyalty must be combined with solid technical training and proven ability. Above all, however, Cyrus understands that his position as leader, as the apex of the command pyramid, necessarily makes him a model figure: whatever he does will be imitated by society as a whole. He must therefore present himself as an ideal citizen before a public far larger than the one he encounters in everyday life.

This is where fashion comes in. Cyrus knows he is a mediated politician –perhaps the first in history. Thousands of men, entire kingdoms, will never see his face. Dozens of peoples will only ever see images of him, hear stories about his figure, listen to narratives about his person. It is in that mediation that cosmetics find room to operate. Xenophon writes: "Cyrus considered it necessary that rulers distinguish themselves from the ruled not only by their actual superiority, but also that he should persuade them by means of striking effects".

Clothes and makeup are those striking effects, those machinations, those deceptions that Cyrus deems necessary. The Cyropaedia goes into detail: the monarch orders garments specially designed to conceal any physical defects and to emphasize the virtues of his body. An army of tailors and dressmakers in the service of the state. Under his long trousers he wears shoes with double soles and heels to appear taller and thus be visible in speeches and public displays. He uses makeup to make himself look more handsome than he really is. He turns fashion into a political tool to communicate to the masses the justification for his rule, which is none other than his own excellence.

Cyrus does the opposite of what is recommended in the Oeconomicus: here cosmetics are a useful lie, aimed at an exceptionally broad audience that needs exemplary figures. We are no longer dealing with an intimate, closed community, but with an empire that stretches to the limits of human imagination. "King of the Four Corners of the World", Cyrus' official title, is not far from Warhammer 40,000's "God-Emperor of Humanity". Just as the only thing that saves souls from the chaos of the Immaterium is the Emperor's charisma –always divine, always performative– the only way to do politics in the face of absence is to become a presence through cosmetic mediation: the spectacular image that will be retold, the beauty that is ready to be described and testified to, the calculated rupture, CFK's Jessica Kessel shoes or Milei's four jackets.

A Test

So what do we do today? Is the world of social media a world without mediations, or, on the contrary, a world in which we have mediated the very mediations? In the answer to that question lies the seed for thinking about the links between fashion, cosmetics and politics. How much distance is there between rulers and ruled? How is an affective political bond built? Have we demolished the barriers that once separated private life from public life, or have we merely multiplied the barriers of entry to increasingly smaller circles that double down on the thresholds guarding what is private?

If our world has shrunk, if –as since the Fourth Age of the Sun– all roads are now curved and none of them reach Valinor, perhaps all that remains is to denounce the enigmatic and captivating power of the lie, since all ties to its usefulness have been severed. Those who think this way will take up arms in the name of sincerity, which is nothing more than the constant denunciation of an Other who is never genuine. In other words: until what time is one really drinking mate? A few months ago, in response to the performativity of men's fashion trends, Ash Callaghan pointed out the trap in this dynamic: you can always call out the performance of the performance of the performance, in an endlessly recursive loop.

If, on the contrary, nothing essential about human beings has changed –if our age is no more exceptional than any other, and our fantasies of uniqueness are merely the dreams of those who live in times less interesting than they imagine– then we still need to think of fashion and cosmetics as indispensable tools for our relationships with others and, therefore, for politics. If we believe that intimacy still exists, if we still trust in that stubborn impossibility of communication that makes us get ready –think of ourselves, revise ourselves, represent ourselves– in front of another, then fashion is a universe we cannot afford to abandon.