Note: This article was translated automatically from Spanish to English using AI.

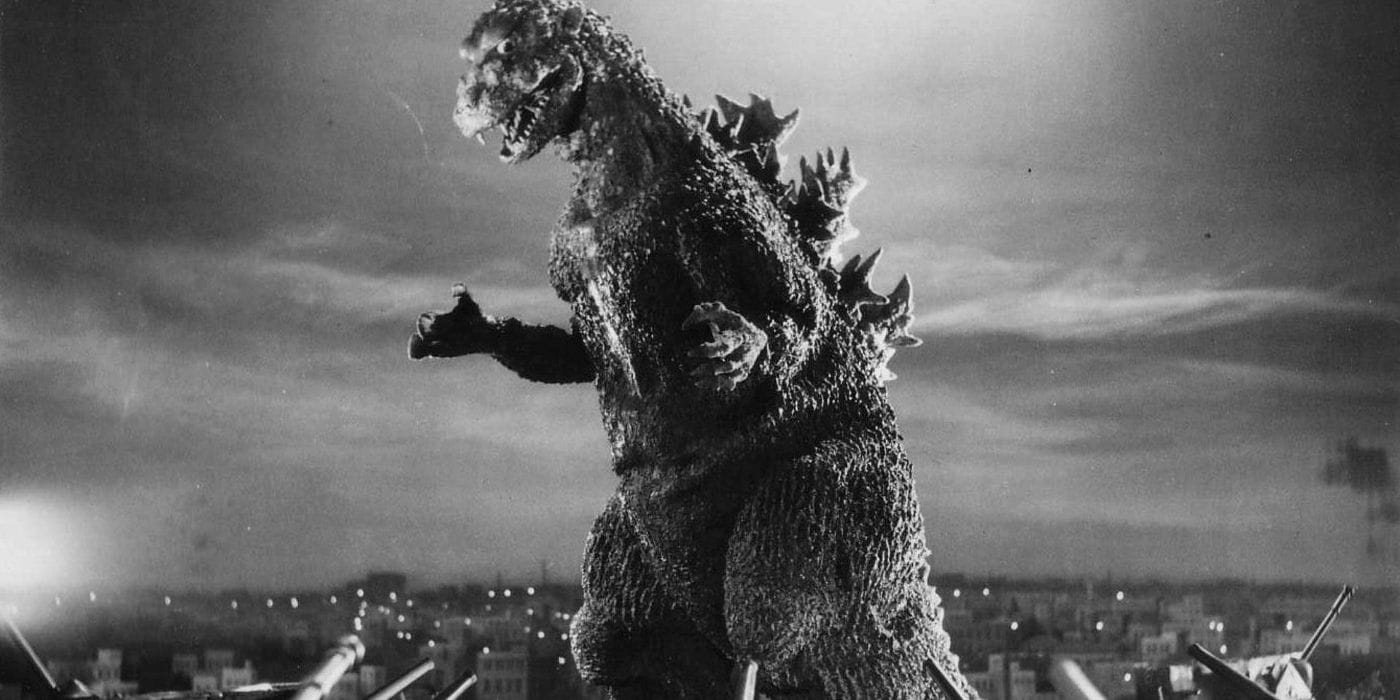

Gojira (1954), the original film directed by Ishiro Honda, is completely beyond any attempt at measurement: it is a total masterpiece. Everything that came after is, to varying degrees, a repetition, a franchise attempt, a collection of narrative tropes, each with more or less aesthetic value, but ultimately they are caricatures of the first film. It's not that they lack value; they do have it. Within what one can recognize as camp or kitsch aesthetics, which we will define later. However, the first film is a different beast, and that’s what we will attempt to recap in this article. The original has a philosophical depth that the rest of the saga lacks. Or at least not until Shin Gojira or Gojira Minus One.

Most of us entered the Gojira (or Godzilla, as we know him in non-Japanese speaking countries) universe through other films in the franchise. I, for instance, first encountered it by renting a VHS at a video store, which I’m almost certain was Gojira Vs Mothra. A nearly incomprehensible delirium for the mind of an eight or nine-year-old. Later on, the infamous Godzilla (1998) would be released, the first attempt at Westernization that left us with the soundtrack as its best feature.

Godzilla as a Metaphor for Japanese Trauma

Gojira was born as an allegory of what happened to Japan during World War II. What happens to Japan as a nation after defeat, after American occupation, after the impossibility of having an army, in other words, defending itself against an existential threat?

The canonical reading of Gojira is that the monster serves as a metaphor for atomic terror. That is to say, the fact that nuclear weapons were used awakens Gojira, who reacts by wreaking havoc on Japan. Now, this interpretation has, in my opinion, a couple of issues. It wasn't Japan that used nuclear weapons, but the United States. And Gojira, in its 1954 version, doesn't attack New York but Tokyo. In other words, Gojira's emergence is a double punishment: Japan not only had to endure the two nuclear attacks but also faces Gojira's assault. This interpretation of punishment can only be sustained from the perspective of the 1998 Godzilla. At least in the sense of “punishment” for hubris. You drop an atomic bomb on Bikini Atoll, and a lizard mutates into a giant monster that destroys your city. The revenge of Mother Earth by other means.

That's why it's always much better to go back to the original source and draw one's own conclusions, whether they align with the more or less canonical interpretations or not. By watching the original, one can recognize that there exists a moral dilemma related to atomic terror, but it comes in a different package. Gojira attacks Tokyo, while Dr. Daisuke Serizawa is developing a definitive secret weapon to defeat Gojira. Although he was initially developing it for other reasons. This is where the moral dilemma central to the film arises, which will also be central for Japan. Serizawa constructs a device called the Oxygen Destroyer, which has the capacity to annihilate living organisms and, therefore, to annihilate Gojira.

Although one might initially think that the dilemma Serizawa faces is quite trivial since he essentially holds a device to eliminate the main problem plaguing the film's protagonists, he explicitly questions whether it is right to use a weapon of mass destruction to stop a monster. Serizawa's question is, in fact, the question Japan might ask about its role in World War II: Were the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki ethical? What would Japan do in an inverse situation? Serizawa ultimately accepts his role as a new Oppenheimer, using the Oxygen Destroyer to annihilate Gojira and save Japan.

However, as one might expect, he takes his own life in that mission to ensure the Oxygen Destroyer can never be replicated again. Essentially, it’s Ishiro Honda’s way of communicating to Oppenheimer that if he had an ounce of honor, he should have done the same. Bathe it and record it, Oppenheimer. How do you repair honor when you are more monstrous than the monster?

The Kaiju as a Symbol

Until writing this article, I was almost certain that Gojira inaugurated what is known as “Kaiju” cinema, which means “monster” in Japanese. But not just any kind of monster, but giant monsters. A popular narrative trope in 1950s cinema, resulting from the combination of various cinematic artifices: stop-motion animation, the use of miniatures, forced perspectives, and, of course, editing. These cinematic techniques allowed for the creation of those films that would be the seeds of science fiction but in a pulp style, which were the production conditions for Gojira.

Namely, “The Lost World” (1925), based on the novel published in 1912 by Arthur Conan Doyle. One of the first films to use stop-motion technology to showcase dinosaurs on the big screen. An idea that would also lead to the creation of the classic King Kong (1933). Coincidentally (or perhaps not), Gojira is a combination of two words: gorira (gorilla) and kujira (whale). A very fitting name for a sea monster whose direct ancestor is, precisely, the king of the apes.

But we are also forgetting another equally significant film that bears a striking resemblance to Gojira, which is The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953), whose translation into Spanish and the metric system would be “The Beast of 36,000 Meters Deep.” It tells the story of a giant lizard that invades New York after being freed from its Arctic ice prison due to atomic bombs. Now, this is the film that inspired Gojira and the canonical interpretations of it. It’s also worth noting that the film is inspired by the short story “The Mermaid” (1951) by Ray Bradbury, published in “The Golden Apples of the Sun.” This is another beautiful link in this chain that takes us from Arthur Conan Doyle to Ishiro Honda and shows us how the canon intertwines with itself.

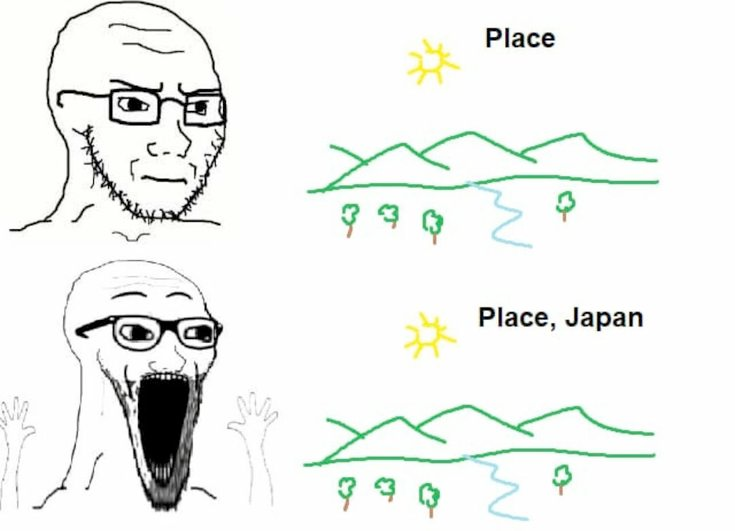

So why does Gojira acquire the status it has now and not The Beast From 36,000 Meters? Well, perhaps there’s some truth to this meme. Although it’s also true that the Japanization of certain tropes, whether from science fiction or religious themes, or even trivial things like horoscopes, ends up creating an appealing reflection for the West. This is the case with Evangelion and Saint Seiya. Western cultural elements reinterpreted through the Japanese cultural kaleidoscope. Upon their return to the West, they produce fascination. But generally, Japanese authors add a level of drama and tragedy that transforms superficial elements into clear reflections on the human condition. And it is precisely this that makes Gojira what it is.

When those elements appear, Gojira shines (besides when it unleashes its nuclear breath). In the good Gojira films, we don't just see destruction: we have a special theme that the author addresses. In the original, Ishiro Honda speaks to us about defeated Japan and its monstrous condition.

And in recent years, we have had two more installments that follow this path. Shin Gojira (2016), directed by Hideaki Anno, problematizes the institutional paralysis of modern Japan, trapped in post-war politics and the difficulty in facing a new overwhelming threat (China?). Shin Godzilla is a film about the state, a bureaucratic drama.

Finally, Minus One (2023) by Takashi Yamazaki revisits themes of honor, guilt, and the reconstruction of post-war Japan. It’s the story of a coward who does not commit Sepukku and lives in disgrace. Minus One dramatizes honor from a different, civil, and human perspective.

If you've never seen anything from the King of Monsters, these three are excellent places to start.

Godzilla, the Sublime and the Horror

The kaiju is not just a giant monster. It is a symbol. And symbols function as spaces where humans project internal states, whether conscious or unconscious. The monster did not choose to be a monster, nor is it to blame for nuclear tests, and it is certainly not responsible for its monumental disproportion compared to humans.

The monster is there, buried, hidden underground, like the living memory of something that no longer exists. In a way, it represents an excess of meaning, a kind of manifestation of the sublime, in the romantic sense of the term. That is, an excess that provokes shivers, admiration, and terror. Like the God of the Old Testament, like nuclear detonations, like Tetsuo.

The emergence of Gojira is associated with all those human feelings but fundamentally with a sense of smallness resulting from the distortion of scale. This is how ants must feel about us. In fact, it is quite significant that the American B-movie cinema that spawned “the beast from 36,000 feet” occurs precisely in that logical inversion: giant spiders, ants the size of tanks, and so on.

That seems to be the trick of kaiju cinema, of Kong and Gojira, the inversion of the scale of the human. And yet, humans always recover from that initial shock and somehow end up controlling the giant monster. So it’s not just the feelings that generate the manifestation of the sublime but how humans, despite everything, manage to maintain their sanity. This is something that the very Imanuel Kant elaborates on in his “Critique of Judgment.”

It is, in part, what connects Gojira with Moby Dick and Cthulhu. In all three works, humans confront three oceanic natural forces with more or less similar fates: Ahab's self-destruction, the madness of the one who saw Cthulhu, and Serizawa's suicide. We can also think of the three beasts as more or less contemporary versions of Leviathan, the biblical sea monster.

Gojira as Camp or Kitsch Idol

In the opening paragraphs of this article, we mentioned that there is a whole phase of Gojira that would be more codified within an aesthetic that we could define as kitsch or camp. It is, in general, the most popular facet of the King of Monsters and is associated with a very marked phase within the productions of Toho, Gojira's parent company. Each phase spans a number of years and is broadly identified with some general idea.

The Shōwa era (1954–1975) is the birth of the myth as a nuclear allegory that leads to popular and camp kaiju cinema. The Heisei era (1984–1995), or the “versus” Gojira era, revisits the nuclear threat in the context of the Cold War and faces various enemy monsters, from King Ghidorah to Mecha Gojira. The Millennium era (1999–2004): characterized by formal experimentation without fixed continuity.

The Reiwa era (2016–present): more author-driven films like Shin Gojira and Minus One (the monster verse films can also be included). The eras also coincide with changes in the emperor of Japan.

In any case, the Shōwa era is the one that interests us the most. On a general level, it is responsible for the special effects cinema known in Japan as tokusatsu, which also includes Kamen Raider and Ultraman, in addition to what we know as Super Sentai that came to the West in the form of Power Rangers. All these Japanese productions have something of camp.

In her essay Notes on Camp (1964), Susan Sontag defines camp as a sensibility: a way of seeing the world that privileges artifice, exaggeration, and the unnatural over seriousness, psychological depth, or realism. Almost from its beginnings, it has also been associated with queer culture; the term comes from the French expression “se camper,” which means to pose (in front of someone) in an exaggerated way and was related to sex work and drag.

The Shōwa phase begins with an absolute tragedy—the 1954 film is anything but camp or kitsch—but over the years, Godzilla transforms into a pop icon, protector of humanity, and fighter against increasingly colorful and extravagant monsters. That’s where camp appears, but not as an original intention: it appears retrospectively. The visible models, the obvious costumes, the exaggerated roars, and the delirious plots generate today a camp pleasure because the cinema takes itself seriously while time makes it theatrical.

On the other hand, the brilliant Federico Klemm pointed out in his television cycle “the telematic banquet” that kitsch is

an aesthetic category of our contemporaneity that has nothing to do with a systematization of bad taste, but with an exacerbation of the artificial and the excessive

A definition that fits well with this era of Gojira cinema and is reflected, for example, in its lines of toys.

Conclusions

As we have seen from a bird's eye view, the aesthetic legacy of Gojira (ゴジラ) is undeniable. From the sublimation of atomic terror to the popularization of camp aesthetics, the influence it has built and the roots from which it is woven provide us with enough material to keep adding countless entries to our canon. From the concept of Kaiju to Super Sentai, Gojira's introduction allows us to add a series of elements that, while present in other entries, did not have the level of fertility demonstrated by the giant Japanese reptile. With all this baggage incorporated, we can continue diving into the waters of pop culture to further the theoretical construction of our collection. That’s what all this is about. Without further ado, Gojira leaves us with a legacy as vast as he is, which is why he holds, without any contender to challenge him, the undisputed title of King of Monsters.