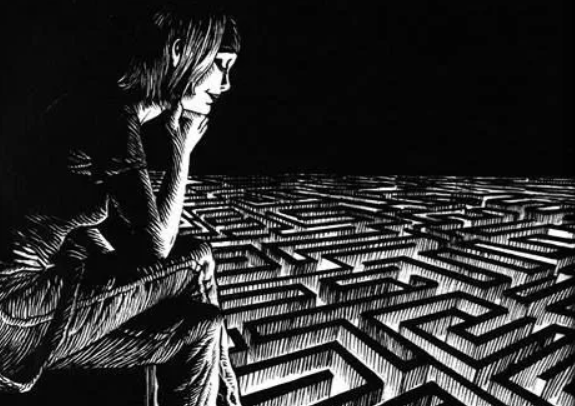

The lure of horror calls to us in any format, and comics pack at least 70 years' worth of nightmares. Starting more as a subgenre, accompanying adventure, or with monsters presented as obstacles for primitive comic book heroes, horror changed its skin and kept reinventing itself in order to stay relevant. Precisely, there's so much to read that it's easy to get lost in labyrinths that always lead back to the same names.

Like the Crypt Keeper, today I will be your spectral host to take you on a tour through an infernal library that celebrates everything scary. With recommendations to start reading while we review the history of horror in the panels.

Like a Zombie: Horror in North American Comics

During the early years of "contemporary" comics as we know them –that is, post Action Comics #1– horror entered the panel as part of the adventures but not as the main focus. Monsters popularized in cinema, such as Bela Lugosi's Dracula and Boris Karloff's Frankenstein, began to appear in comics as caricatured takes or recurring villains in anthology titles or adventure comics of the era. It wasn't until the '50s that horror moved to the foreground with the publisher EC Comics and its terrifying triad: The Vault of Horror, The Haunt of Fear, and Tales from the Crypt, more popular due to its '90s TV series.

Editor William M. Gaines had inherited EC Comics from his father as a business for educational and religious comics, but when it didn't work, he eventually pivoted to action anthologies. Over time, the crime stories were getting a bit darker and were attracting the attention of older readers. So Gaines and his co-editor Al Feldstein decided to lean in creating the titles that immortalized the publisher. The key, and somewhat the industry model for a time, was to make visually striking comics, with stories that had a social commentary and endings where poetic justice reigned supreme over people who did evil. Another key point of their success was having highly innovative artists like Graham Ingels, Wally Wood, and Jack Davis, among others.

Shortly after the publisher's success, psychiatrist Fredric Wertham released his book Seduction of the Innocent (1954), where he spoke of the "bad influence of comics" on children, mainly those involving crime, mysteries, and horror. This led to the creation of the CCA, the Comics Code Authority, which began to put a approbal seal on comics approved by this hyper-strict censorship system where, for example, the words terror and horror were prohibited in magazine titles.

Just like the "rock trial" in the '80s, when Dee Snider of Twisted Sister testified before Congress, editor William M. Gaines had to go and defend his publications before a hearing in the U.S. Senate. It did not go well, and EC had to cancel its horror magazines. The spirit of these types of publications only returned in the '60s with the magazines Eerie and Creepy, and the character Vampirella, all from the publisher Warren, who were able to circumvent the code since the format was more like a magazine for adults, like MAD magazine, than a comic book anthology.

In the '70s, thanks to the success of the anthologies and the CCA easing up on censorship, suspense and horror titles arrived at DC Comics and the then-young publisher Marvel Comics. House of Secrets, from DC Comics, introduced Swamp Thing in 1971, which would become key a decade and a little after at the hands of Alan Moore. Meanwhile, Marvel released Tomb of Dracula, with vampire stories including the hunter Blade, and in parallel, characters like Ghost Rider and the title Son of Satan began to reintegrate superhero comics with the paranormal. Thanks to the authors who established the new theoretical template for '80s comics (like Frank Miller with Batman or his Daredevil and Alan Moore with his Swamp Thing), raw, violent, and macabre stories began to appear even in the most mainstream titles.

The '80s had their perfect evolution in Vertigo, an imprint that DC Comics created in 1993 to make adult comics and which yielded important titles that could be categorized as horror, such as the Flinch anthology, Neil Gaiman's Sandman, and Garth Ennis's Preacher, among many other publications. During these years there was also a boom in independent publishers like Kitchen Sink Press, which published the horror story Black Hole by Charles Burns, and also the publisher Dark Horse, with Hellboy by Mike Mignola.

Over time, DC wound down Vertigo –although the return of the imprint was announced at New York Comic Con 2025– and horror comics moved to independent publishers, notably IDW and Image Comics, where they found a space to experiment again without the pressure of the mainstream. Although we can name many titles from the 2000s onwards, like Garth Ennis's Crossed, I believe Robert Kirkman's The Walking Dead was the one that managed to shine a light on the genre again, revitalizing the zombie genre.

Japan: Powerhouse of Yokai and Gore

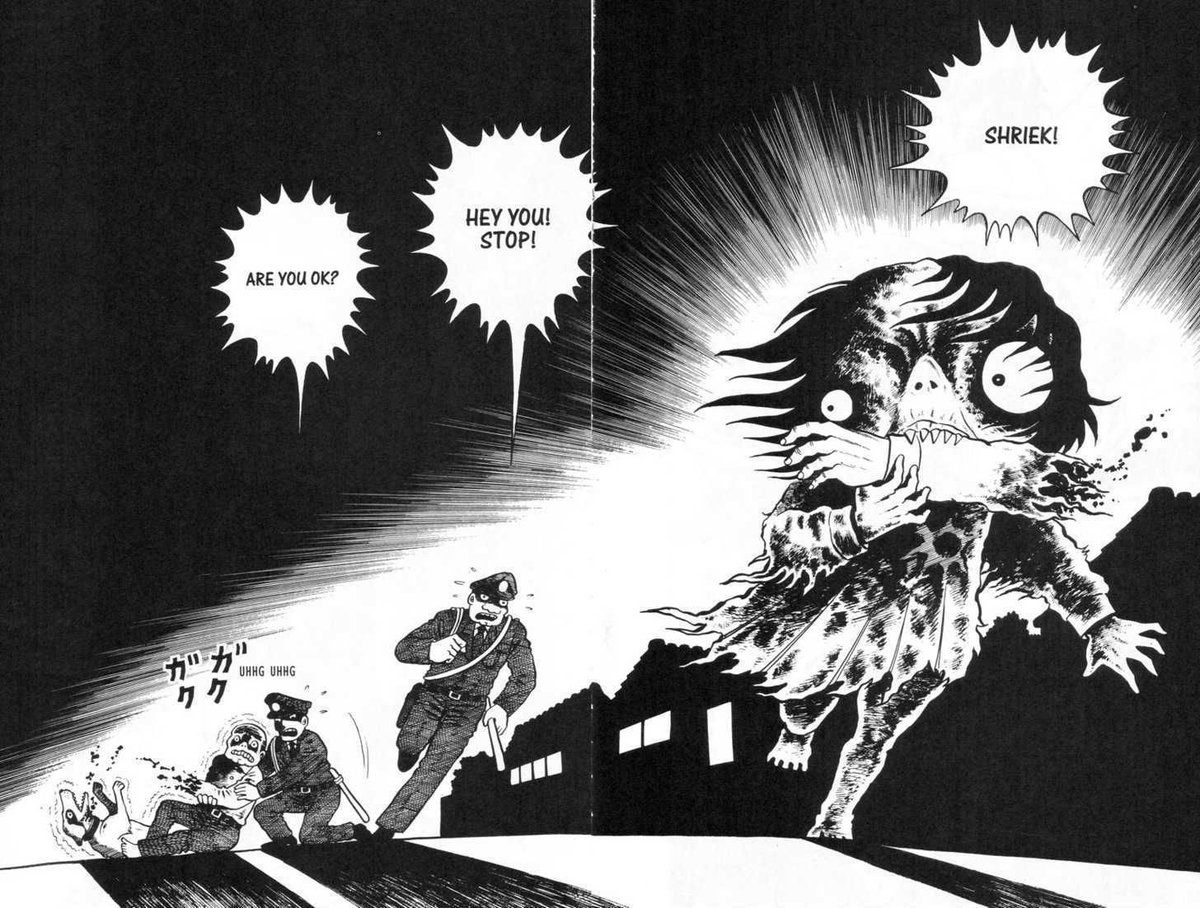

In the '50s, while censorship invaded comics in the United States, in Japan, manga began a journey with the horror genre at such an extreme level that it would eventually cross paths with pornography. In 1959, the character of Kitaro (GeGeGe no Kitarō) by Shigeru Mizuki was born, considered the driving force behind Yokai culture (monsters and spirits from Japanese folklore). Although there were already manga with these types of stories, the character of Kitaro managed to make them part of a world of their own, mainly aimed at children yet unafraid to go dark. And the years that followed were indeed dark because Japanese horror entered a phase of body horror, psychological horror, and post-atomic social horror, guided by masters Kazuo Umezu, Hideshi Hino, and Go Nagai.

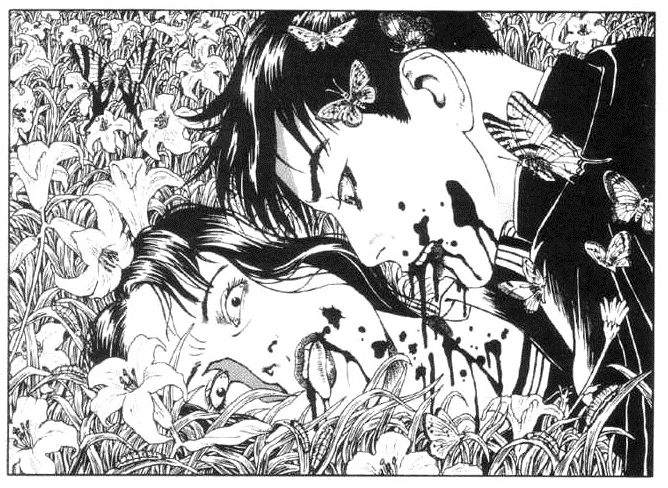

After emerging with the custom that manga can be for all ages, horror had to measure up to a population that had lived through nuclear horror and lived in tension, like a traumatized society that constantly had violence very close to their lives. This fermented, and what I like to call post-body horror, the Ero Guro, was born from it. Ero Guro Nansensu, which means "erotic grotesque nonsense", is a Japanese art movement from the 1920s that pushed back against moralist movements of the time. This subgenre of graphic violence and decadence presented very explicit stories that visited all kinds of perversions. Among the most popular authors we find Suehiro Maruo and Shintaro Kago, but there is much material unknown in the West and themes that may run afoul of content laws. However, at the more accessible end –where you'll find Maruo and Kago–, we can enjoy a horrible but incredibly drawn festival.

And we cannot overlook the one who is today considered the king of Japanese horror, with a style that marked a new stage in manga: Junji Ito took horror in manga to a plane of social and psychological horror, with dark forces beyond human comprehension. He is an author with a large body of work, of which Uzumaki, about a town cursed by a spiral-shaped entity, is always recommended, but he also has very good anthologies of short stories like Shiver, which is where I believe his neat yet grotesque drawing most excels.

Argentina and Its Monsters

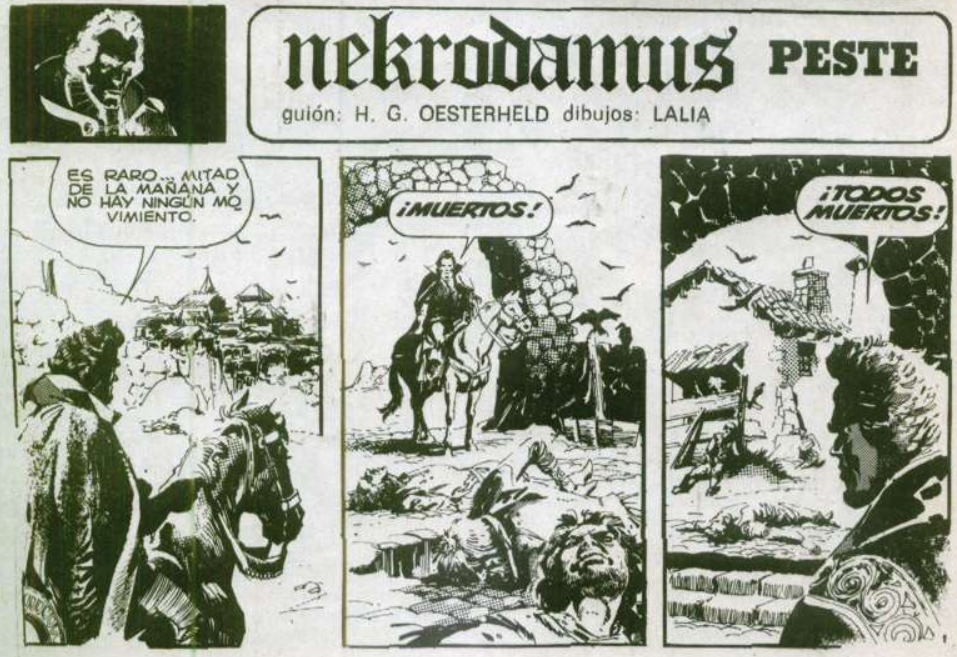

Argentine comics have a tradition in horror that began with anthologies inspired by the magazine Creepy, which we mentioned earlier. In fact, much of the material from Warren was published starting in the '70s through local publishers Mazzone, SG, and Mo.Pa.Sa, in magazines like Dr Tetrik, Tenebrarius, and Noches de Terror. But if we think of national authors, we have to highlight the masters Horacio Lalia and Alberto Breccia, who scared readers with their tremendous drawings in fundamental works. Breccia has, among his extensive career, the hits of Mort Cinder, with a script by Héctor Germán Oesterheld (creator of El Eternauta), and the Myths of Cthulhu with Norberto Buscaglia, first published in Italy in Il Mago magazine, in 1973. Horacio Lalia, for his part, worked on Nekrodamus starting in 1975, another character created by Oesterheld, and also on adaptations of Lovecraft, Poe, and H.G Wells, among others.

Closer to our times, Argentine comics had a renaissance since 2010, with the appearance of new publishers and spaces. Horror was part of that movement in which I would like to highlight works like Mega and Legión, by Salvador Sanz, standing out as a great monster artist; and El síndrome Gustavino, by Lucas Varela, with his more cartoon style reaching super dark places in Carlos Trillo's script. And I don't want to fail to mention the last stage of the Fierro magazine in Página|12, where many authors were published, such as Fer Calvi with his story Lo blanco del ojo, where he mixes crime with horror.

All right, enough talk –let's read.

Recommended Comics for Nighttime Reading

Horror We? How's Bayou? (Haunt of Fear #17, 1953)

This story, with script and art by Graham Ingels, has explorations that approach body horror, mad killers in the style of Ed Gein and the family from the Texas Chainsaw Massacre and what could be a proto-swamp creature like Swamp Thing or Man-Thing. In this classic, a doctor gets lost on the road and arrives at the home of bloodthirsty brothers.

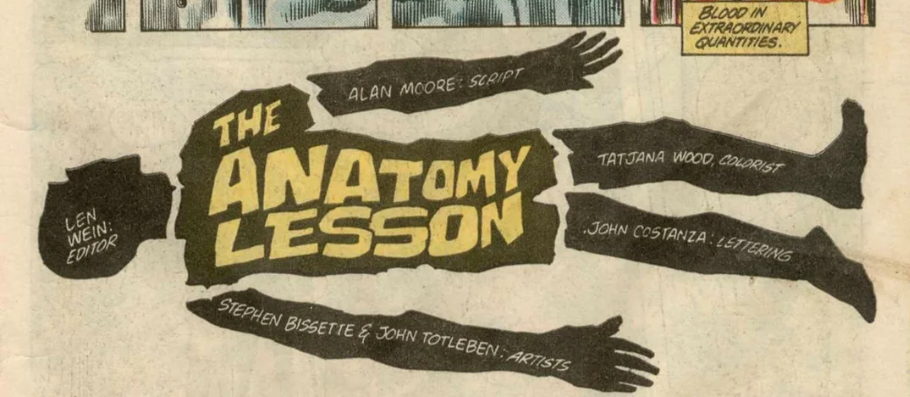

The Anatomy Lesson (The Saga of the Swamp Thing #21, 1984)

A turning point for the comic by Alan Moore with art by Stephen Bissette and John Totleben. A scientist performs a dissection on Swamp Thing to discover the monster's secret. This crazy horror story has a philosophical focus that debates existence and identity. It will challenge your mind.

Daredevil: Redemption (2005)

With a script by David Hine and art by Michael Gaydos, this story of the Marvel hero takes us to a small town in Alabama where a boy is brutally murdered. Matt Murdock travels as a lawyer to defend some young people, accused for being "odd" and into heavy metal in a place like a small town with big-city problems. The story is based on the real-life events of the case known as the "West Memphis Three". A very dark story where the superheroics were left out and what entered was a top-tier horror thriller.

Ice Cream Man Vol. 1 (2018)

It could be described as a horror anthology with a touch of bizarre humor. Each issue is a self-contained story with new characters but which have a common thread through The Ice Cream Man. A benign-looking figure who, as the comic says, can be friend, foe, god –or demon. A very good trip, I recommend it. One of the current comics I liked the most. The script is by W. Maxwell Prince and the art by Martín Morazzo.

Cursed Creature (Kyōfu! Jigoku Shōjo, 1982)

To get us in the mood for horror manga. Kyōfu! Jigoku Shōjo, by Hideshi Hino, is a small but shocking story that sets the stage for this great artist's world. A father abandons one of his newborn twins for being a deformed monster, and this poor creature ends up in what is called the World Cemetery, a super heavy dump where the little girl will begin her revenge against humanity. Gore and drama with that Japanese social commentary about discarded people.

The Vampire's Smile (Warau Kyūketsuki, 1999)

Suehiro Maruo tells us a vampire story with a touch of soft Ero Guro to start. A student is turned into a vampire and joins a gang of vampire teenagers who not only want blood but also want to experiment with all kinds of violence and perversions. If you're OK with this level of explicit content, I recommend continuing with his best-known title Midori: Shōjo Tsubaki... approach with caution.

Disfigured (2007)

There is a lot to read from Argentina, but I always liked this graphic novel, the first by Salvador Sanz. Darío participates in experiments on perception and sees something he shouldn't have seen. Now, with the veil of reality broken, he has to survive not only what is on the other side but also his own existence.

Beyond these 7 recommendations, a number chosen on purpose to ward off the evil spirits we might summon with so much horror, you can also immerse yourselves in the names and works I mentioned when we reviewed the history of horror comics in the United States, Japan, and Argentina. I hope you enjoyed this reading about fear in the panels and that you will join me on a future tour of this infernal library... Mwahahahaha!

(He walks away laughing and with a candelabrum with melted candles, disappearing into the darkness)