December is the month when classes come to an end in our country. Students of all levels prepare to take any outstanding exams or simply enjoy their vacation until the new school year begins. In 2025, my son had his first experience in an institution: he attended the three-year-old class at a local kindergarten. The school break threw him off; his routine was disrupted. "When is the afternoon?" he asks, thinking about snack time, his favorite meal at any time of day that still has some sunlight. And it's understandable: time is something immaterial, and his only concrete references are the classroom and nighttime. So, with the longer days of summer, one o'clock or seven-thirty in the afternoon can feel indistinguishable if there's nothing fixed and tangible to separate them.

We can't think about time without linking it to activities and things. In our daily lives, this translates to the morning coffee, the afternoon mate, and the evening glass of wine. Throughout the year, it’s reflected in winter jackets and summer Hawaiian shirts. In life, it’s represented by the Ninja Turtle action figures from childhood in the nineties and the atorvastatin box for cholesterol management today. The timeline can keep expanding, but at the cost of personal experience. Let's take a look.

Many times, many things

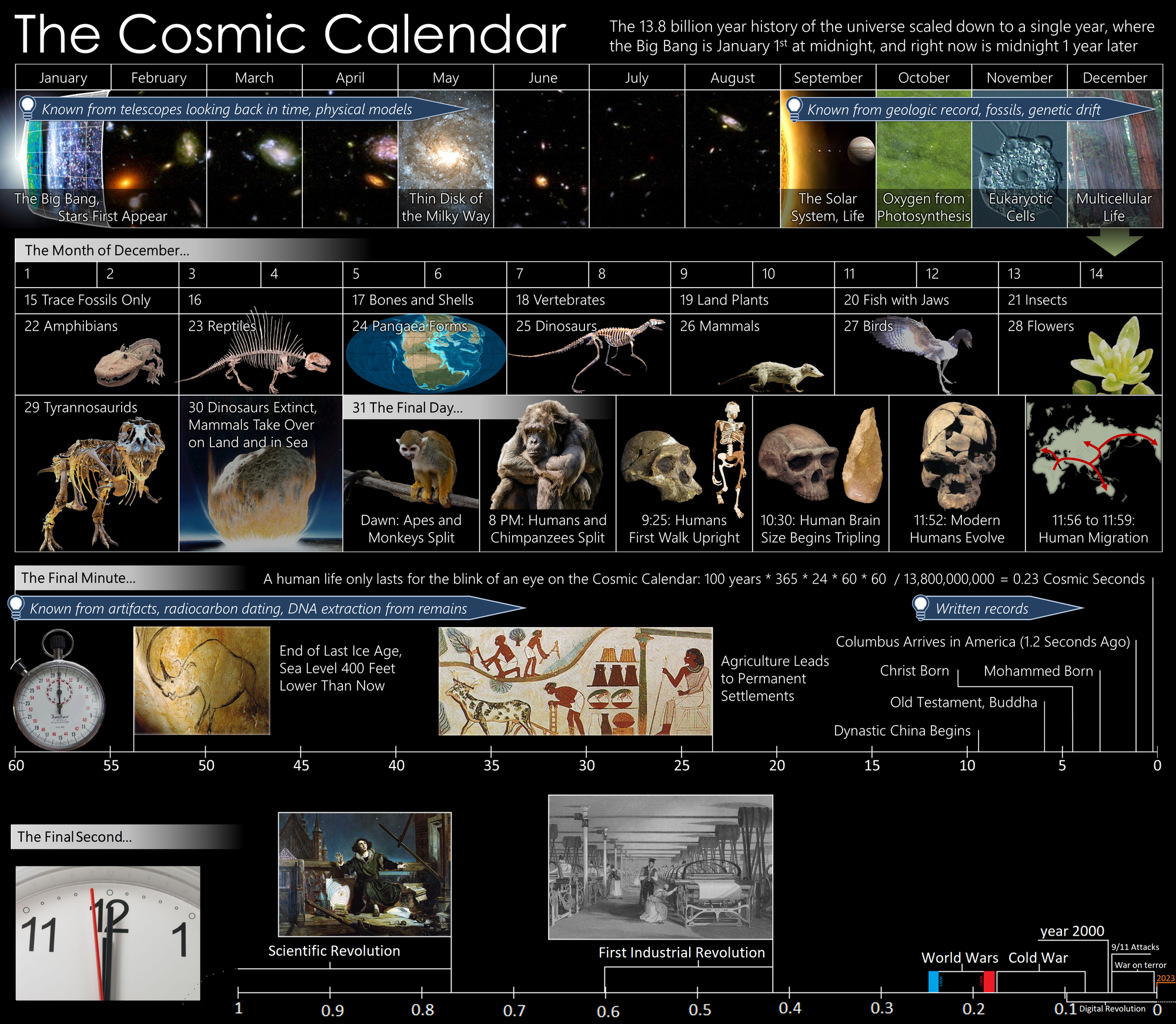

Carl Sagan, in his series Cosmos (1980), popularized the “Cosmic Calendar”: it’s a scaled-down version of the history of the universe over a year. The nearly 13.8 billion years of the universe are proportionally distributed across the 365 days of the Gregorian calendar. By making this parallel, January 1 at 00:00 marks the Big Bang; on September 9, the solar system forms; on the 21st of that month, the first signs of life appear; and only on December 31 at 23:52 do humans emerge. This exercise allows us to perceive not only the depth of time in our universe but also the insignificance of our existence.

Now, to achieve this educational tool, Sagan drew on information from physics, geology, paleontology, archaeology, and history. These disciplines do not conceive of time in the same way because their questions differ. For example, while for a historian knowing the exact year, month, or even day of an event can be crucial to their research, for a physicist or geologist, it’s irrelevant because, when studying qualitatively different phenomena, they work on a scale that involves thousands, millions, or even billions of years. Even an archaeologist, who is temporally and disciplinarily closer to a historian, uses chronological cuts that may seem imprecise to any history professional if applied to their field. Thus, depending on the question being asked, vast time spans or very brief periods may be useful. However, all these disciplines share one thing: they do not observe time directly; rather, they think about it, measure it, reconstruct it, and understand it through things.

Things to locate us in time: the guide fossil

Writing about the Big Bang, the formation of the solar system, and “cosmic things” really exceeds my grasp. So, let’s focus on something more earthly. We’re talking about a type of thing that allows us to account for the time it belongs to simply by its presence: the guide fossil.

The guide fossil is a paleontological remnant that allows us to place it in a relatively narrow timeframe based on the context in which it is found, that is, the rock it is part of. Not every fossil is a guide fossil; it must have four characteristics. First, this type of fossil must belong to a species whose populations were numerous in the past. Additionally, it’s important that it has some identifiable feature. Finally, the species must have had a wide spatial distribution and a limited temporal existence. The ammonites, a subclass of extinct mollusks represented by thousands of species, meet all these requirements, which is why they are used to assign relative time to the rocks in which they were fossilized. Different species of ammonites succeeded each other over a period ranging from 400 to 66 million years ago, and thanks to extensive prior classification and correlation work, identifying one of them allows for a relatively precise temporal reference within that vast span.

Although the concept of guide fossil originates in paleontology, archaeology has adopted and redefined it to address its own chronological problems. Archaeological “guide fossils” are not natural remains (like ammonites) but cultural ones (like a fragment of pottery), so their origin is not linked to natural processes (like fossilization) but to social processes (like pottery production). Therefore, in archaeology, the use of “guide fossil” is not literal but conceptual: specific material remains are used to chronologically locate a site before resorting to absolute dating methods, like carbon-14.

From Clovis points to Coca-Cola bottles

In archaeology, then, time is recognized not only through absolute dates but also through certain objects whose features anchor them to specific moments. These cultural “guide fossils” allow for a relative and provisional chronological placement of an archaeological site even during the excavation process.

The Clovis arrowheads were used for hunting megafauna and are indicators of the late Pleistocene (between 13,500 and 12,500 years ago) in North America. These are striking projectile points, crafted from stone, extremely standardized, thin, and wide, designed to penetrate the skin of Pleistocene megafauna. Their standardization is such that even from a fragment, it’s possible to envision the rest of the complete point and assign it to that type, and therefore, to that specific time. Moreover, these points not only tell us about a time and a way of obtaining food but also about the skill of the artisans in their manufacture and the areas for sourcing raw materials, among other things.

As we move a little closer in time, ceramics can also inform us about chronology. In Europe, terra sigillata is a precise indicator not only of the Roman Empire but also of a specific period of its dominance, spanning from the 1st century BC to the 3rd century AD. In South America, particularly in the Andean region, the discovery of ceramic vessels with specific shapes (like aríbalos or the so-called duck plates) allows for the identification of contexts linked to Inca presence, from the early 15th century AD until the arrival of the conquerors. One of the characteristics of empires is to impose themselves and mark their presence in the territories they dominate. Thus, in the past, ceramics became a material and everyday marker of that domination and, today, a fairly reliable chronological indicator within the archaeological record.

Finally, glass artifacts like bottles are good indicators of temporality for archaeological sites, especially those from the 19th and 20th centuries. For example, a rural settlement from the late 19th century that lacks written records of its foundation or operation can be dated by its trash. These glass objects, mass-produced and widely distributed (just like ammonites!), signal not only a specific historical moment but also the expansion of new forms of consumption, circulation of goods, and social organization characteristic of an industrializing world.

Thus, from a Clovis point to a Coca-Cola bottle, and including imperial ceramics, some objects survive their users and become markers of their time. They inscribe an approximate date, as well as a way of living, thinking, and inhabiting the world.

What things distinguish our time?

With the Industrial Revolution and the expansion of capitalism, the number of things increased exponentially from the 19th century onward. The 20th century and the first quarter of the 21st century we are traversing have witnessed a true overproduction of “guide fossils.” A bit due to technological advancement itself, another bit due to planned obsolescence, and yet another due to the constant need to create new demands to sustain the productive system, the last fifty years have shown us a diversity of objects that can be assigned to increasingly precise time periods.

If Incan duck plates can be dated back to the 15th century AD, the little yellow ducklings that were used as head accessories had a very specific temporal anchor, at least in our country: May and June of 2024. The more ephemeral an object is, the more precisely it marks its time. Today, the last of those ducklings hang (and perhaps a bit faded) in front of some shop in the Barrio Chino, while their brief reign is challenged by labubus, which in turn are beginning to experience the inevitable decline of many goods in late capitalism.

As an exercise, and considering that Google Trends has been tracking searches since 2004, we can see that interest in labubus peaked sharply in our country between June and September of 2025, enough to make their way into the bags of the national team members. The mp3 player, a guiding fossil of the 2000s, began to fade out in 2010, linked to the rise of smartphones. Meanwhile, the netbook started to gain visibility at the end of 2008. The younger sibling of notebooks entered the market promising lighter weight, essential but basic functions, and an affordable price. It peaked in sync with the Conectar Igualdad program and saw a final spike during the pandemic, likely in search of a budget-friendly option for remote work and study.

These three cases are merely illustrative of things that surround us (or once surrounded us) and that, during their use, we didn't realize their end was so near. It's not easy to identify what distinguishes an era while you're living it: generally, it's the subsequent generations that point out the milestones of each historical stage. Perhaps it's not the objects themselves that define a time, but rather a way of doing that materializes in them. And the prevailing way of doing today is characterized by short expiration dates, premature disposal, and constant novelty.

Resisting Through Objects

In a world saturated with things (and, paradoxically, with less and less space to store them), it's necessary to transcend the barrier of mass and unconscious consumption of objects. The time spent checking out what's new on Temu (the famous “bolucompra”) could be used to rummage through drawers, attics, or warehouses (yours or others') or even to tinker with some object found on the street. There’s probably something to fix, restore, or simply clean, thus resisting, at least a little, the logic of constant and unnecessary replacement.

In the face of the immediate obsolescence of objects, the act of carefully choosing some of them, preserving them, maintaining them, and using them also helps to build our personal history. And that’s where objects exceed their intended function: they become generators of identity, memory, and feelings. It's the little chair of your grandfather versus the generic, interchangeable, and anonymous Nordic chair. It's your mom's hammer (which was also your other grandfather's) versus the 55-tool set for $39.99 from the “Best Seller” section of Mercado Libre. It's the wooden cutting board with thousands of scars from your grandmother for cutting vegetables against the plastic board advertised as BPA-free. And it’s also the china plate of a stranger who decided that the sidewalk was a better destination than the cupboard and solves that purchase you were going to make at the Chinese bazaar. Thus, the old-new object not only fulfills the function for which it was conceived but also becomes laden with history, anecdotes, and emotion. A high life result, not just in the utilitarian sense but also in the spiritual, stemming from a low tech material decision.

In archaeology, the process by which humans recover and reuse objects that were discarded or left unused by previous societies or generations is known as “reclamation.” However, it’s not just about reusing things, but about inserting them into a present where they are re-signified and gain value beyond the practical. Reclaiming them to use, but also to tell stories: transforming things into carriers of narratives and anchors of memory.

“When is afternoon?” my son asks again, as his Lego minifigures from the Marvel universe battle with my (now his) Bucephalus from the Galactic Hawks, renamed Galactus.