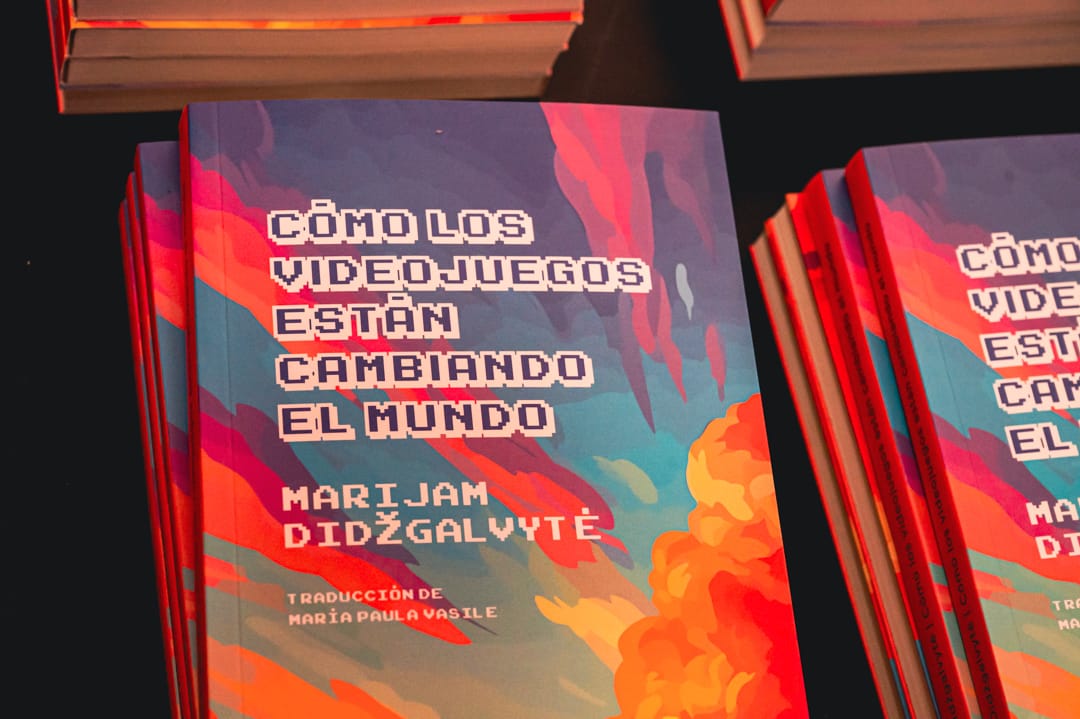

Marijam Didžgalvytė is a Latvian-Tatar journalist specializing in video games whose book Everything to Play For: How Videogames Are Changing the World was translated and published in Argentina by the Godot publishing house. Marijam practices her craft in major outlets such as Vice, The Guardian, and GamesIndustry.biz, among others. She has taught courses and classes at the University of London and works as a marketing manager at an award-winning video game studio.

She is basically an industry insider with a left-wing political tradition. She took part in Game Workers Unite (the video game workers' union), and her book is clearly rooted in Marxist materialism. It's a combination that might seem strange at first, but really isn't. Beyond her professional credentials, it's clear that Marijam is an avid video game player who knows the industry both from the inside and from having grown up in parallel to its evolution. That's a very good sign: this isn't someone who picked a topic to research just in order to write a book, but someone writing about a world she actually inhabits. Anyone between 35 and 45 will find in the book a journey through the games that left a permanent mark on us. First success.

Marijam's book is a great introduction to contemporary video game culture and how it became what it is today. It's full of facts I didn't know but somehow suspected. This is an industry whose annual revenues surpass those of cinema and music combined. It is expected to reach 500 billion dollars by 2028. It's estimated that in 2023 around 3 billion people played video games. A game like GTA V sold 200 million copies and outgrossed Avatar, Avengers: Endgame and Avatar: The Way of Water, the three highest-grossing films in history. The book works both for readers with no specific knowledge of the industry and for players who know the world of games perfectly or quite well but perhaps lack a systematic framework for thinking about it –that's where I place myself. Second success.

Now, Marijam has a critical view of something she knows and deeply loves. And this is where the book can become a watershed for readers. Those looking for a story focused solely on the evolution of video games as a specific art form are likely to be disappointed. What the book aims to do is analyze video games as an industry: what kind of culture prevails in the ways games represent the world; what role the major studios play; what's going on with stereotypes; which are the main graphics engines; what happens with online storefronts; what role companies such as Microsoft, EA Sports, Rockstar, Nvidia or Steam play in the industry. But beyond those questions there is an even more fundamental one: how can an industry be sustained within a system that constantly seeks to increase computing power while its raw materials are extracted in a quasi-criminal way from the so-called Third World? Yes, you open the book to see what's going on with Super Mario and end up looking up information about coltan mines, rare earths, and child exploitation. Third success.

We were able to talk about all of this with Marijam during her visit to Argentina, where she came to present her book at the annual edition of the Feria de Editores (FED).

The Left and Technology

Marijam's book is part of a small but intense contemporary tradition –one that I think at least one of my own books also belongs to. We could say that at this point it almost amounts to a genre of its own. Four titles are not quite enough to claim there's a fully-fledged genre, but I'd add another one I wrote an editorial report on to determine whether it was publishable or not. And my sense is that there are quite a few more books of this type floating around out there. All of these books are more or less the same book, or rather, they all defend the same thesis: this or that technology (usually a digital one) is a battlefield.

That is, even though the uses of a given technology might lead us to think it only makes the world's problems worse, further complicates social relations, and pushes us toward the apocalypse, it's also not true that technology is strictly deterministic. What these books are debating is precisely this: are the evolutionary trajectories of a technology a path pre-inscribed in the ideology out of which it was built? Marijam's book –along with books like Cryptocommunism, Technofeudalism and my book on memes– seems to circle around the same question or set of questions: does this technology have a predetermined evolution? Is it possible to change the pre-programmed course of a given technology?

I remember giving the same talk on memes for the umpteenth time at a UNA conference in 2023, in the Banco Provincia auditorium, in front of a meagre audience that included the head of the degree program, or something along those lines –I don't quite remember his exact title in the nomenklatura. The man raised his hand and declared that "the algorithm is fascist". By that point I was pretty fed up with the progressive self-help into which any talk about politics and social media tends to degenerate, so I told him –half as a premonition– that this very lack of understanding of information technology we were talking about was one of the things that would lead to Milei becoming president. This whole detour is basically to say that trying to problematize a technology is a rather uncomfortable task that almost always ends badly for the person doing it. Why? Well, because there is something at the root of many of these debates that is very hard to fix just by conjuring words.

Information technology is built on a material and economic infrastructure that cannot be transformed without a social revolution. Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Nvidia, TSMC, ARM, Intel, ASML or AMD are the backbone of the techno-oligarchic complex. These are the companies at the very top of the stack that produces computers, software and infrastructure –the layer that will determine the course of life for everyone on the planet. And it's not as if Tencent, SMEE or SMIC, the Chinese counterparts to these "Western" giants, operate according to a different logic. On the contrary, they seem to fully reinforce the same business model.

So all the "particular" problems around technology –whether we are talking about video games, data infrastructure, privacy, artificial intelligence or cryptocurrencies– operate on top of this pre-existing material base. In other words, it doesn't matter whether or not we manage to transform the ethos of a particular industry: the extraction of rare earths in Africa will remain one of the main drivers of civil wars stoked by the powers involved.

And this point, in particular, is one that Marijam understands very clearly. Fourth success.

Even if all video games took place in a kind of fictional Barbie Land, where everything was peaceful and everyone agreed and was kind, empathetic and generous, both in and out of the game; Even if we eradicate all violent, sexist, xenophobic and highly addictive video games, we would barely be able to quell the disaster. It is crucial that we do not become distracted by the intrigues and injustices within the games (as important as they may sometimes be), and focus on the real goal: dismantling this guilty and catastrophic material reality that thrives today and rebuilding something much less reprehensible.

If you are interested, you can read the full chapter here.

After this devastating paragraph, it becomes clear that nothing can be changed without changing its material foundations. The book also underlines, however, that even if we can't yet stop the violence generated by the extraction of rare earths, there is still room for politics there. Or rather: the only way to find any solution at all is through political action.

Marijam ends her book by saying there is far more politics in a game made without subjecting its workers to crunch than in a game with a non-hegemonic female protagonist that chewed up and spat out the people who made it.

In that sense, the emergence of the Godot engine is nothing short of paradigmatic: an ethical way of making technology, non-monopolistic and technically impeccable at the same time. Once again, even if technology is constrained by its material conditions, there are still design spaces that enable political action –and open up the possibility of a world that's a little less fucked up.