Borges dedicated a story to him. Houellebecq, an essay. His work has been adapted to film many times –generally poorly. Alberto Breccia adapted it into comics –a masterpiece. He has more than one tabletop role-playing game dedicated to his work. Countless metal songs were inspired by his prose. Howard Phillips Lovecraft is a superstar.

In life he didn't do so well, at least not with criticism. Lovecraft's stories and novels were for mass consumption: they were published in pulp magazines, so called because they used cheap, low-grade pulp paper. In these reduced weight newsprint, a novel form of aesthetic imagination was born, a radical strain of speculative literature that redefined the horror and science fiction genres, and paved the way for new forms of political and philosophical thought. If there is a name for what Lovecraft founded, it is not exactly a literary movement but something else, that name is probably "cosmic horror". To understand it, though, we need its context.

An introduction to Cosmicism

The place is Providence, in the state of Rhode Island. The year is 1890. Lovecraft was born into an aristocratic family. During the first decades of his life, that fortune decreased significantly. He later married Sonia Greene, who supported him for several years, until the funds ran out again. Until the end of his life, Lovecraft lived off what he earned as an author and editor for pulp magazines.

Moving away from the merely biographical, we can identify three main sources that nourished the foundations of cosmic horror: Gothic literature, scientific materialism and pulp culture. With these three elements, crossed by the conservative political ideas he inherits from his family, Lovecraft produced a completely new work.

Of the Gothic tradition (and especially from his greatest influence, Edgar Allan Poe), Lovecraft derives a way of thinking the terrifying as an intrusion of something external into reality, which exacerbates it and takes it beyond the bounds of the human. Furthermore, he takes an interest in decadence, the degradation of the high and the pure. From scientific materialism, which at that historical moment had become a weighty philosophical movement, he developed a vision of the world that places humanity not as the center of the universe but as another component, of contingent existence and in no way special. Especially influenced by Darwin's followers, and combined with his political conceptions, he displays a series of strongly racist and eugenic ideas which form the central basis of a good part of his stories. Finally, from the pulp literature to which he belonged, Lovecraft takes a method, a way of writing: adventure stories, with mass appeal, but with a certain linguistic virtuosity aimed at producing a distinctive sensory effect.

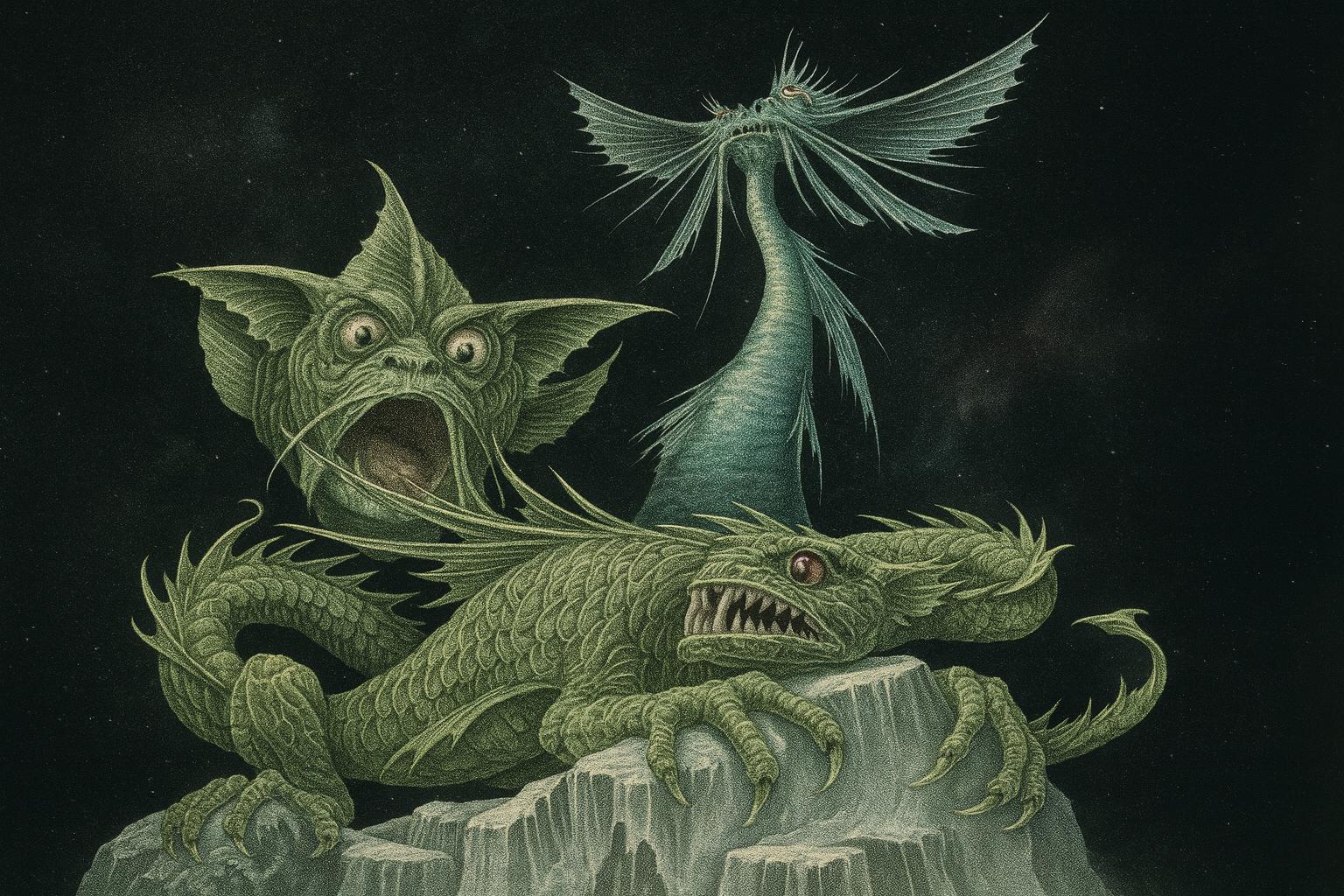

This unusual combination gives rise to what we call cosmic horror. Lovecraft seeks to build beings that exist in spatial and temporal scales infinitely greater than humans, and therefore are not governed by the same rules. The figures that appear in his stories (with names like Cthulhu, Dagon, Nyarlathotep) are inconceivable and incomprehensible to human reason. What it is about, for Lovecraft, is attempting –always, in some sense, unsuccessfully– to describe entities that resist comprehension altogether. His stories are situated from a human perspective, but that point of view is utterly overwhelmed by his encounter with an absolute otherness.

A consequence of this is that the Great Old Ones (one of the names Lovecraft gives to these beings) do not necessarily have malevolent intentions for humanity, much less for specific human beings: the protagonists of these stories or novels always meet the beings almost by chance. If Cthulhu seeks the destruction of Earth, it is only so he can ascend from the sunken city of R'lyeh: our species is too insignificant to be considered a factor. We are nothing more than specks of dust.

In light of cosmic horror, all previous horror literature is revealed as too human; anthropocentric, perhaps we could call it. A vampire, a ghost or a demonic possession are phenomena legible within human terms, understandable in relation to our morals –which they ultimately invert. They are like us, only partially more powerful and located on the side of Evil. For Lovecraft, on the other hand, the true horror lies in the fact that good and evil cease to be intelligible categories when modern science has shown that humanity is an accident of biology: therein lies its cosmic character.

Mythologies?

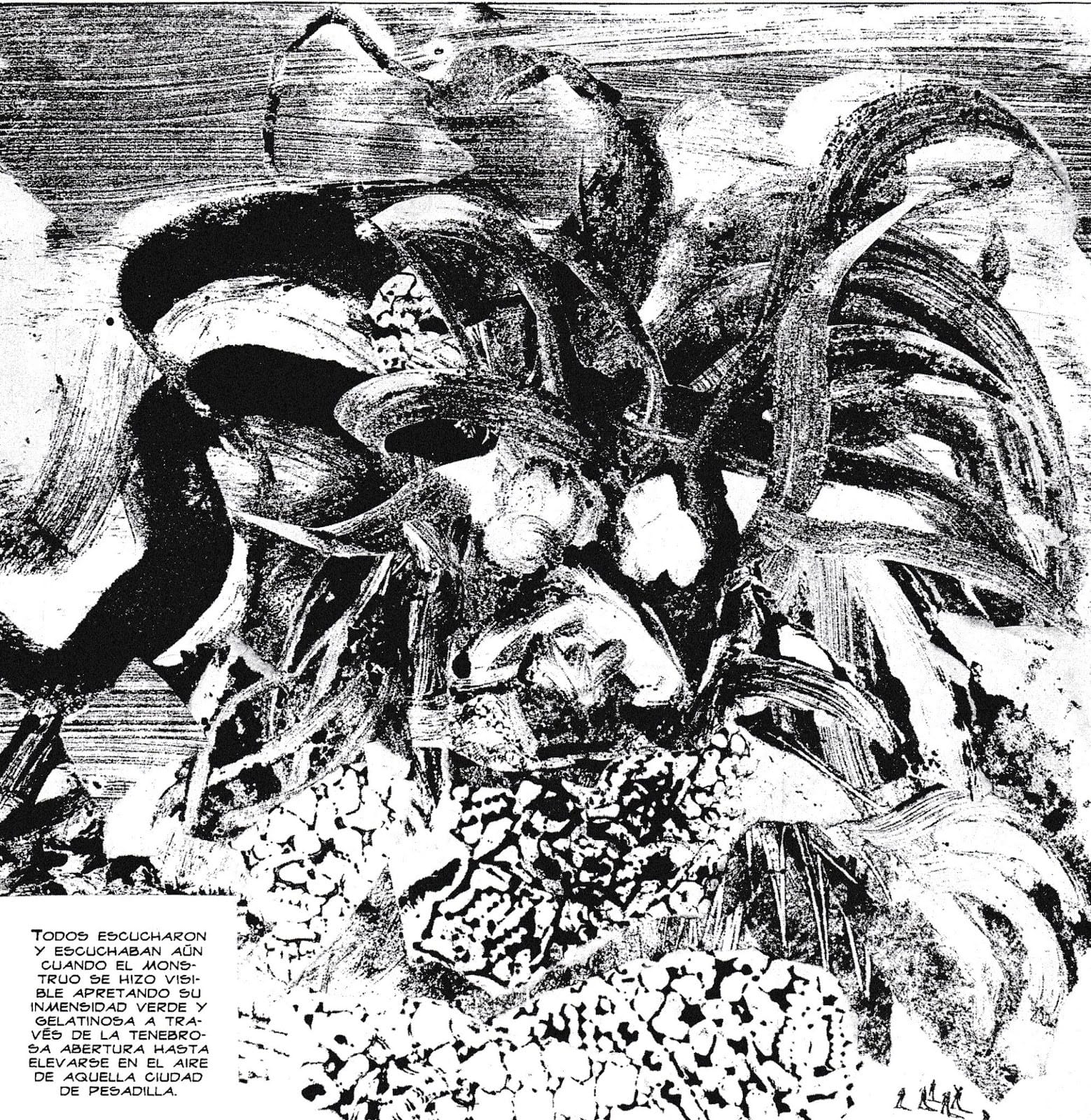

A meteorite falls on a Massachusetts farm and reveals a substance of indescribable color that poisons the land and makes people sick. Nyarlathotep appears in ancient Egypt, taking the form of a pharaoh. A mute old man plays the cello and his music opens up an infernal and formless dimension beyond the stars. A group of explorers discovers colossal mountains in Antarctica with cities older than man, made up of impossible architectures and populated by amorphous beings, the Shoggoths.

Lovecraft wrote dozens of stories, many unfinished; some so long that they are considered almost short novels, others so short that they are just sketches. Among the most important are "The Call of Cthulhu", "The Colour Out of Space", "Rats in the Walls", and the early ones "Dagon" and "Polaris". The novels are later: they correspond to his last decade of life and are mostly short. They stand out At the Mountains of Madness, The Shadow over Innsmouth and The Dunwich Horror.

How are these stories linked to each other? Are they part of the same universe? Many share some elements. For example, beings usually have epithets: Nyarlathotep is "The Crawling Chaos"; Shub-Niggurath, "the Black Goat of the Woods with a Thousand Young"; Yog-Sothoth, "the All-in-One and the One-in-All". There is also a fictional tradition: that of the Necronomicon, the mythical grimoire written by the mad poet Abdul Alhazred that contains all the known information about the Great Old Ones. Miskatonic University supposedly keeps a copy, but Lovecraft wrote that other libraries have copies, including the University of Buenos Aires. These are the general parameters of what is usually known as the Cthulhu Mythos.

But you would have to be careful with this word: the mythologization of these stories is rather a phenomenon after the death of the author, promoted by some members of the so-called "Lovecraft Circle", followers who knew him in life and set out to continue his work. Some sought to turn the Great Old Ones into a religious pantheon, establishing hierarchies and kinships between Nyarlathotep and Shub-Niggurath, Azathoth and Yog-Sothoth, etc.

Lovecraft himself sometimes played with these classifications in his letters, but was careful to include them explicitly in his stories. What happens is that with this widespread reading, there is a risk of losing the most interesting part of Lovecraftian cosmicism: its absolute inhumanity, the impossibility of reterritorializing the infinite strangeness of the Great Old Ones into categories understandable to terrestrial society.

The same applies to descriptions, because Lovecraftian horror lies precisely in what happens when we perceive something that is beyond our senses and our cognition. Many times words like "amorphous", "formless", "chaotic", and references to non-Euclidean mathematics and impossible angles appear, self-similar, recursive shapes, colors that fall outside the human visual spectrum, incomprehensible words that cause terrible effects. And, as we said previously, it is a question of scale: we are talking about beings older and vaster than our planet, whose existence is greater –and more terrible– than ours.

Lovecraft stands on the frontier of the sensible: if the facts and beings he describes were simply impossible to perceive, there would be no effect. Instead, horror occurs in the slightest contact with the strange, which reveals a much greater infinity that the human mind cannot reach. On this frontier, madness always appears. Bottom line: No, Cthulhu is not an octopus-faced guy.

An Inhuman Morality

However, we are not just talking about "cosmic literature" but specifically "horror". It may seem contradictory that a writer so adept at scientific materialism, who in his decentering of the anthropic perspective considers himself aseptic and hyperrational, includes a fundamental ethical condition in his literature. After all, while the Great Old Ones are not in themselves bad, they are enemies of humanity: of reason, of human consciousness, even of our existence. The cults that worship them tend to be apocalyptic and fundamentally antihumanist. Is it necessary? Couldn't these beings exist in a state of absolute indifference towards the human species?

We can give several answers to this question. The first is that, as we previously mentioned, Lovecraft writes within two literary traditions: Gothic horror and pulp fiction; These are the narrative frameworks underpinning his work, and from which he does not escape. But this is not enough to explain the meaning of the horrible: Lovecraft's move is to equate the non-anthropocentric with the anti-human. This is a central ethical decision: by undermining the foundations of reason, the outside world is revealed as a chaos of pure contingency, appearing only ordered as part of a fiction of consciousness. And this turns out to be nothing more than an accident of the mindless drift of evolution.

But there is a third explanation that we cannot leave aside, and it is linked to the eugenic question. What is horrifying, for Lovecraft, results from a state of biological degeneration which corresponds directly to ideas of racial purity that, we know, the writer held. For some readings, cosmic horror is inseparable from this vision of humanity as something that can degrade if mixed with lesser beings. This is associated with both the "scientific" developments of the first quarter of the 20th century (before the Holocaust finally threw eugenics out of the legitimately scientific realm) and with the conservative political ideals of the social class to which Lovecraft belonged, as well as his successive declines in status. However, if we move to the biographical field, we can also find an important change: letters from his final months, published only in recent years, we find a Lovecraft who expresses regret for his racist views.

After all, cosmic horror arises from a crossing of dimensions: on the one hand, the aesthetic, linked to the limits of the sensible; on the other, the ethical, associated with this image of degradation. But the political consequences of this crossing can be very different. Two cases exemplify it perfectly: the story "Rats in the Walls" and the short novel The Shadow over Innsmouth.

Both tell the discovery of a repressed origin that destabilizes the identity of the protagonist. In the first, a man discovers that his ancestors were cannibals, part of a perverse cult of the Great Old Ones, who had created an underground city where they used humans as livestock. Images of slavery, and possible rebellions, are central to Lovecraft's work: They have a central place in his masterpiece, At the Mountains of Madness. The discovery causes him to experience a kind of schizophrenic break and become, too, a cannibal: the inheritance of racial degeneration is a condemnation that animalizes humans. (To complete: don't look up the name of Lovecraft's cat, which had the same name as the mascot in this story)

The protagonist of The Shadow over Innsmouth makes a similar discovery: his ancestors copulated with mysterious amphibian beings, and he himself descends from this inter-species crossing. Faced with this revelation, he also undergoes a subjective destabilization, but the description is completely different. There is no story of racist paranoia, but rather a certain ambivalence, perhaps even pleasure: "The tense extremes of horror are shrinking, and I find myself queerly drawn into the unknown sea depths, instead of fearing them. I listen and do strange things when I sleep, and I wake up with a kind of excitement instead of terror."

Lovecraft is generally considered a pessimistic writer. Michel Houellebecq titled his book about him Against the World, Against Life. His stories never have happy endings, nor could they: Human forces are infinitesimal compared to the cosmic antiquity of chaos. However, as Graham Harman points out in Weird Realism, Lovecraftian protagonists still manage to wound or strike back, however briefly. And there are also endings like that of The Shadow over Innsmouth, where a destiny beyond the human does not seem like a curse but, perhaps, a condition of happiness, of redemption from present pains (the structure of that novel is not far from being a perverse version of "The Ugly Duckling"). Exploring what happens when humanity does not occupy the center of the scene but a minor place, Lovecraft found a path of openness to the alien.