Under the conditions of digital memory, it is the loss itself that has been lost. (Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life, “The Slow Cancellation of the Future”)

Villa Epecuén, in Adolfo Alsina in Argentina’s Buenos Aires Province, was one of the country’s most popular vacation destinations between 1920 and 1970. It had a population of 1,200 people, plus thousands of summer tourists. Its thermal waters were said to be “miraculous,” capable of curing any illness. But in 1985, a flood overflowed the lake and submerged the town completely. The entire population had to be evacuated. Thirty years later, when the water finally receded, the ruined buildings resurfaced. Those remains became a tourist attraction in their own right. Today, people visit that desolate landscape to photograph the shattered houses.

Only one resident, Pablo Novak, stayed behind. Novak spent 33 years living in different ranches around Epecuén, guarding what was left. “I’m in this place simply because it makes me happy,” he used to say. He remained there until his death at 93, after which Villa Epecuén was officially declared deserted.

Villa Epecuén is not the first ghost town, nor will it be the last. Abandoned places multiply after economic, military, or environmental crises. In every case, people are forced to leave behind everything they know. And yet there is always a pull to return—even when conditions have been altered forever.

That same spectral, abandoned air can be found in virtual spaces that have fallen into disuse. In recent years, platforms like MSN and Fotolog shut down. MySpace, launched in 2003 and later eclipsed by Facebook, is now effectively read-only: you can’t publish anything new, and most of its images and songs are broken links.

My High School Forum

There’s one particular place I used to visit when I was a girl: my high school forum. It brought together students from different years, and even people who no longer attended the school at all. When someone new joined, they’d introduce themselves, and the forum would welcome them as if they were a new neighbor moving in. Compared to real-world adolescent social life, it felt like a more sheltered, supportive space—an open conversation about whatever you wanted.

That page no longer exists. The screenshots I found today come from the Wayback Machine, a website designed to archive the internet’s past. Wayback’s bots crawl the web, following links and saving snapshots of what they find. That’s how it still preserves images from many sites that are now inactive. Walking through that archive feels like wandering a cemetery.

I open one of the last Wayback snapshots. It’s from the thread “Presentaciones,” and it contains two lonely comments from 2014:

From 2014, the last threads created also survive: “El olvido” and “De cómo hacemos para que vuelvan los usuarios históricos.”

The final message, dated June 2015, makes me think of a post-apocalyptic world—a solitary survivor broadcasting a radio signal through static. Or the last inhabitant of a ghost town, watching it empty out little by little.

Born as Ghost Towns

Just as some platforms died slowly, others were born as ghost towns. In 2021, Facebook renamed itself Meta and launched what it framed as its bet on the future: the metaverse. “Metaverse” wasn’t a new term—it was coined in 1992 in Neal Stephenson’s novel Snow Crash, describing a fictional shared virtual world where characters connect. The novel also popularized “avatar” as the image a user projects in virtual space.

The metaverse that emerged from literature has had more life than the real metaverse promoted by Mark Zuckerberg, which never took off in a post-pandemic moment when people wanted to be outside again, not strapped into clunky headsets to enter a virtual reality that still felt awkward and crude. The spaces sold as the future are empty. Download a VR game and you’ll likely find lobbies full of bots and hardly a human in sight.

The title Snow Crash refers to the static you see on a malfunctioning monitor. It echoes the famous opening line of William Gibson’s 1984 cyberpunk novel Neuromancer: “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.” Gibson’s fiction helped cement terms like “The Matrix” cyberspace long before the technologies existed that could approximate those worlds. Literature anticipated both the possibilities and the dangers of virtuality.

In the early 2000s—well before Meta’s metaverse—online role-playing platforms like Second Life emerged. Launched in 2003, it reached over one million active users in 2013. There’s no single objective beyond exploration, social interaction, and the creation and exchange of virtual goods. Though its user base declined, Second Life is still in use today.

There.com is another case: also released in 2003 and similar to Second Life, it never caught on. It closed temporarily in 2010, reopened in 2012 with a paid subscription, and has since lost nearly all its users.

In 2025, a YouTuber named Globert posted a video attempting to “revive” the abandoned game. He wanders through a world he assumes is empty, only to discover a small group of loyal users still there. Fewer than a hundred remain, and they mostly show up for specific events. There’s a real community spirit inside: in a world where most of what exists was created by its members, they gift each other dragons to fly together across the maps, or share the precise coordinates where the stars look best. One user tells Globert: “We know how old and decrepit it is. Everyone who was here went somewhere—many went to Second Life and other places—but when you talk to them you’ll realize they miss this. They never found another place like it.”

The reach of Globert’s video drew many people back to there.com, for the first time or after years away. Most of the comments speak with nostalgia about a “golden age” of the internet that felt more communal.

Mark Fisher writes in Ghosts of My Life that, in Freud’s terms, both mourning and melancholy are bound up with loss: “But while mourning is the slow and painful withdrawal of libido from the lost object, in melancholy the libido appears attached to what has disappeared.”

Today I look for myself in the forum’s archived snapshots, but I can’t find me. There are only echoes of other people I knew. One of them is Kimjoy—immortalized in my mind by his username rather than his real name. We shared thousands of conversations on MSN and on the forum during a few summer months, but very few words in real life. We were fourteen—an age made of confusion. My avatar was a photo of Björk; Kimjoy’s was Anna, a character from the anime Shaman King. Sometimes he called me “Anna,” a name that somehow became his, too. He said she and I were alike. The names and images we used on the forum were another version of ourselves—parallel to everyday life, but no less genuine.

Fisher writes: “Hauntology can be understood as failed mourning. It’s the refusal to let the ghost go—or, which is sometimes the same thing, the refusal to let the ghost leave us.” As I open Wayback snapshots one by one, I think about ghosts.

Where Are the Ghosts of Memory Stored?

Where did the idea that people could communicate through letters come from? We can think of a distant person, we can cling to a close person; everything else lies beyond human forces. (Franz Kafka, Letters to Milena)

People who leave virtual communities are immortalized in traces that never fully disappear. Instead of tombs and abandoned houses, we get old comments and photos surviving in the corners of the internet: digital ghosts. Online, we encounter a past that is incomplete and fragmented. Wayback snapshots are partial and chance-based; what we keep on hard drives can break; storage devices fill up. You can never save everything.

A perfect archive—if it were even possible—would be inhuman. And more information wouldn’t necessarily mean more knowledge. Absence is constitutive of existence; it gives meaning to what remains.

In In the Swarm, Byung-Chul Han argues that the ghosts Kafka sensed in epistolary communication have multiplied: the internet, smartphones, social networks, and other devices are their new incarnation—louder, more voracious. Digital communication doesn’t just detach the message from its sender; it turns it into something that circulates bodiless—without context, without a fixed destination—a spectral matter that replicates itself.

In the Black Mirror episode “The Entire History of You,” most people have an implanted device that records everything they do, see, and hear. They can replay that memory to themselves or project it for others. Faced with a suspicion of infidelity, the episode’s protagonist becomes obsessed with rewatching his own past. He spends more and more time analyzing stored memories and less time living new ones, consumed by the meticulous record of what has already happened. The fear of losing a history—of losing a compilation of our traces—always carries its own dose of anguish. What if I need to return to it someday and it’s no longer there?

When vacation ended and we went back to school, the pace of messages between Kimjoy and me slowed more and more. Something about returning to in-person life pushed that bond into the background. I also sensed something in his last messages—anguish, urgency—that made me step away. We met once in person, in the hallway between shifts, and he gave me a kind of farewell souvenir from that summer: an illustrated copy of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, his necklace, and a USB drive that held all our MSN conversations. He told me things weren’t going well at home, and that I should keep it in case we never saw each other again. We never spoke after that day. Today the USB drive is lost, and MSN no longer exists. There’s no way to go back and review what we said, to check whether my memories are accurate, whether things really happened the way I remember them.

Digital life doesn’t die; it lingers, suspended, waiting to be reactivated. Nothing disappears completely. Think of how many Facebook users remain on the platform after they die, their profiles exposed to the public like mausoleums where messages can still be left. The importance of the specter, as Fisher notes, is that even when it isn’t fully present, it still acts on us.

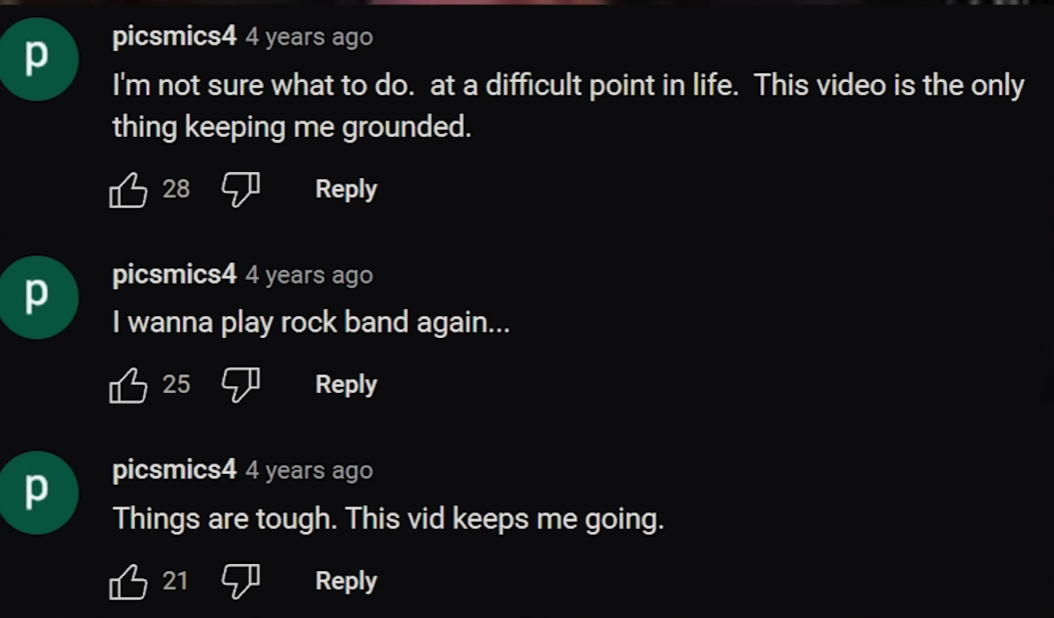

In the video “A Mysterious YouTube Commenter: picsmics4” YouTuber ShaiiValley documents a phenomenon that unfolded under the comments of a 2008 video of someone playing a Rock Band song. It was a personal upload with almost no views—except for one user, picsmics4, who left over a hundred comments across fifteen years. What began as repetitive enthusiasm gradually turned into an accidental public diary: an emotional anchor he returned to again and again. Only when the video went viral thanks to a Reddit post did people notice the conversation picsmics4 had been having with himself for years.

Nearly fifteen years after the first comment, picsmics4 wrote: “One of the best memories I have is playing Rock Band with my friends. I doubt I’ll ever feel that carefree again, but this video takes me back to the good times.” Later, when the story spread, he explained he watched the video when he couldn’t sleep and left comments like echoes into the void: there was something comforting in the fact that the only reply was a familiar song.

In her essay “The Enduring Ephemeral, or The Future Is a Memory,” Wendy Hui Kyong Chun argues that memory is an active process, not a static one. Memory isn’t the same as storage, and information isn’t the same as meaning. To keep memory from drifting or disappearing, you have to preserve it—you have to revisit it to keep it alive.

Virtual Identity: Community and Performance

Again, the Shakespeare paraphrase comes to mind: we are “consumed with that which we were nourished by.” (Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other)

Virtuality allows us to transcend assigned identity. It’s a place where you can experiment with almost no risk, behind anonymity, as if living inside a constant simulation. It lets us build an ideal self—unbound by physical and material constraints—shaping image and voice, stepping beyond the limits of the body.

In Alone Together (2011), Sherry Turkle writes about online role-playing games and argues that the performance behind an avatar can also create a new community of belonging: “It is not unusual for people to feel more comfortable in an unreal place than in a real one, because they feel that in the simulation they show their best (and perhaps most authentic) self.”

Forum users rarely used real photos or real names. Identity was customized through careful reference: nods to films, series, music, hobbies. People made personalized banners with images or quotes. On MSN, you’d also set a status—cryptic phrases meant to generate mystery, or song lyrics.

Digital performance offers the safety of distance—of not putting your body on the line—and yet it also strips you bare. You dare to show things you wouldn’t show in person; you dare to have a style and presence you’d never risk on the street, like an outfit you love but feel is too bold to wear outside.

According to Libertad Borda, fan forums (and arguably any forum) operate through a norm of generalized reciprocity: giving without expecting a direct return. Unlike balanced reciprocity (equivalent exchange) or negative reciprocity (taking without giving), generalized reciprocity doesn’t require participation as the price of admission.

Forums tolerate negative reciprocity to a remarkable degree. Anyone can enter as a lurker and browse without contributing anything. No one has to pay to belong. And yet members still give each other gifts: instructions, advice, illustrations that are thanked and left available to everyone. Instead of accumulating privately, value is redistributed immediately—the same dynamic Globert finds among there.com’s remaining users.

There are fewer spaces like that now, amid digital hostility. The closest equivalents might be platforms like Reddit or Discord, where something of that communal ideal still survives. But those niches coexist with much more massive networks—Instagram, Twitter, Facebook. As social media expanded, so did the internet’s public, once more marginal. Like big cities, that growth produced a kind of anonymous impunity: we don’t know our neighbors, we move invisibly through crowds, and our words can start to feel consequence-free. Our virtual identities changed, too: where avatars once dominated, the selfie now tends to be the default projection of the digital self.

In the documentary series How To with John Wilson, John Wilson investigates questions that seem banal and follows them wherever they lead. In the episode “How To Remember Your Dreams,” he ends up in a comic shop with a member of an Avatar fan club. The group met on a website dedicated to James Cameron’s film, which tells the story of a man who escapes life in a wheelchair through a machine that projects him into an avatar body. When Wilson attends a fan gathering, he meets a group of misfits—people living with disability, depression, and the persistent feeling of not fitting in—who found belonging in that fandom. Among them, the impulse to care for one another remains.

When we find a familiar, sheltering space, we don’t want to let go. Nostalgia for the internet’s past expresses a desire to resurrect it as a place of possibility. It’s a call to return to our ghost towns.

During the pandemic, when streets emptied and people learned to see the world through screens, Kimjoy took his own life. I found out through an Instagram post: a mutual friend shared a photo of him with a caption announcing his death without details. I messaged her; she told me he’d been depressed for a long time, and the pandemic made everything worse. He was 27. When he died, I realized how much weight he still had in my mind: how could something so tiny weigh so much—just a few gigabytes once stored on a lost USB drive?

When I began writing this text about ruins and nostalgia, while exploring the Wayback Machine, I stumbled on a post of his by chance. It was a 2013 thread where Kimjoy explained, among other things, why the forum had closed in 2012 before reopening the following year. When it reopened, he took on the role of administrator. In that post, I discovered he had already put into his own words what I was trying to say.

In 2015, the forum shut down for good. Only the remnants were left, in the form of snapshots. Maybe the last survivors got tired. Maybe the owner finally said “enough” and forced everyone out.

I try to imagine my last day there, but I can’t remember it. I don’t know which threads I opened, which comments I read, what my last words were. I wonder if the others remember what that farewell felt like. How do you let go of the place that gave you your name? And what do you do with its ghost?