If you hear "Korean music", you'll probably picture a group of boys or girls with brightly colored hair, intricate choreography, and the catchiest songs you've ever heard. If you're a bit deeper into it, you might think of pop blended with rap and hip-hop. And yes –this is all part of the K-pop world. But here we're talking about something else.

Korean indie, as the name suggests, is South Korea's independent music scene: artists and bands working outside K-pop's industrial system. The sound is broad –punk to folk, alternative rock to jazz– and it often blends styles. Influences can range from Talking Heads to Otis Redding. There's no single sonic blueprint, but there is a shared ethos: DIY production and a serious commitment to authenticity.

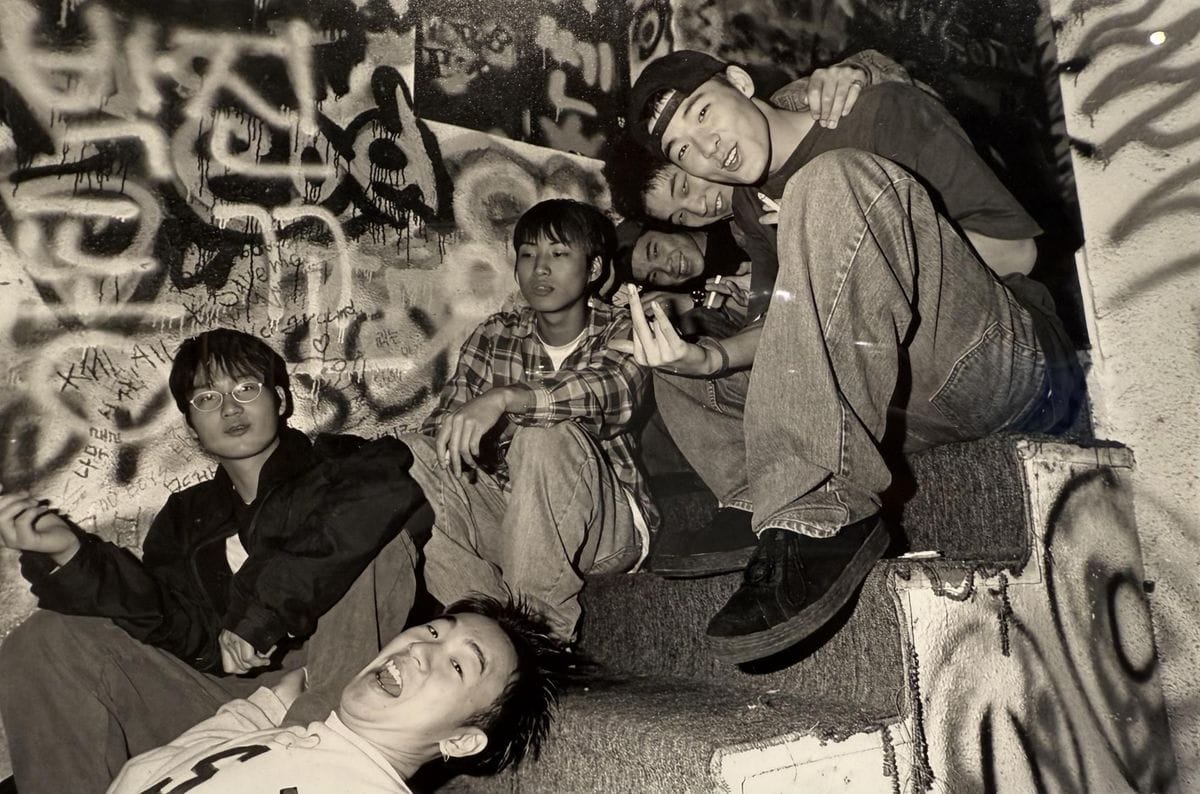

The '90s: Social Change, New Generations, and a Scene Ready to Ignite

First, some context. The '80s in South Korea were grim. Chun Doo-hwan's military dictatorship kept the country under tight political control; press freedom was limited, and dissent was harshly suppressed. Even with rapid economic growth, social tension remained high and artistic expression had little room to breathe. By 1987, pressure from student movements, civil organizations, and mass protests helped open the door to democratic reform.

After the regime fell, a community grew around Hongik University –known for its prestigious Arts department. Students, designers, musicians, and visual artists looked for places to present experimental work without restrictions. Rents were cheap, venues were small, and the area was still far from the tourist hotspot it is today.

Back then, Hongdae wasn't a neatly defined neighborhood so much as a patchwork of streets, plazas, and small venues where these communities met. From the mid-'90s on, rehearsal rooms and "live houses" multiplied, booking emerging bands on a regular basis. Home studios, indie labels, second-hand record shops, instrument stores, and hybrid spaces –part retail, part fanzine and poster display– sprang up alongside them. The circuit also included cafés where people talked gigs, bars that ran themed nights, and galleries that opened their doors to intimate shows.

Club Drug, Club M.I., and the First Spaces of Cultural Resistance

Indie culture's identity is deeply tied to clubs. The rise of teen pop –first pushed by Seo Taiji and Boys, and later by idol groups (as these glossy, teen-oriented acts are known) like H.O.T. and Fin.K.L.– helped set the template for the industrial model that would eventually become K-pop. That's why anyone looking for a refuge outside the mainstream often had to find it in Hongdae.

These spots weren't nightclubs –and they weren't polished places, either. They were tiny rooms that could barely fit twenty to forty people. There was live music, slightly experimental DJs, slam poetry, and all kinds of performance.

One of the first –and most influential– was Club Drug. It functioned as a listening room for alternative rock, punk, and other non-commercial genres. Some of Korea's early punk bands played there, including Crying Nut and No Brain –groups that would later be seen as foundational to the country's alternative rock scene. Club Drug became a home base for people chasing loud, raw, improvised sounds.

Meanwhile, for those looking for something more creative and art-driven –closer to folk, alternative rock, and even electronic music– Club M.I. opened in 1995. According to accounts from the time, it became a hit among art students and self-taught musicians.

Life in these places was precarious. There wasn't much money going around, so musicians themselves kept things afloat. Deals were informal: a door cover, hand-to-hand sales of homemade copies, and reliance on volunteer bookers and promoters. Many spaces were run by people who wore multiple hats –techs who also booked shows, musicians handling production, cover art, fanzines, and DIY video.

Along with other venues that popped up –Velvet Banana, Evans, FF– these clubs built an underground network where K-indie's codes took shape: self-expression, stylistic diversity, informality, social critique, and a strong sense of community.

But there was a major problem: live music in bars and clubs was illegal in Korea until 1999. Owners and musicians had to be extremely careful. Bands played anyway, fans showed up anyway, and the scene grew on the edge of what was permitted and what was marginal. Eventually, under cultural and economic pressure, the government legalized live music in venues –a turning point that shifted the indie scene from underground to a recognized part of Seoul's urban culture.

Legalization changed everything. Suddenly, clubs could book shows officially, sell tickets, and promote events without fearing fines or police shutdowns. The scene professionalized: indie labels (like Boongaboonga Records) emerged, and a new wave of bands began gaining recognition beyond the neighborhood. Later, as the internet took off –and with platforms like YouTube and SoundCloud– independent artists reached audiences abroad.

During the 2000s, K-indie went through a kind of "golden age". Bands could record albums, sell merchandise, play festivals, and circulate through alternative outlets. They were still far from the K-pop machine, but they built a loyal, curious, demanding audience.

Musical Influences

Musically, Korean indie leans toward a hybrid sound: Western influences filtered through a distinct local sensibility. Many bands cite acts like The Flaming Lips, The Stone Roses, or Pet Shop Boys; Oasis and Blur are often among the first names mentioned. There's also a clear pull from Korean popular music of the '70s and '80s –nostalgic melodies, simple progressions, and a particular vocal warmth. In some cases, like Jambinai, those influences blend with traditional instruments. Others, like Hyukoh, fold in sounds from across Asia alongside blues and alternative rock. And bands like The RockTigers play with foreign genres in an ironic key, creating hybrid identities such as "kimchibilly".

Punk and Alternative Rock

Inspired by bands like The Clash, Ramones, Nirvana, and Sonic Youth, many young Koreans found punk as a form of political and emotional release. During the democratic transition, it became a space to shout frustrations, challenge rigid social norms, and try out new youth identities. Crying Nut and No Brain were among the first to adapt these sounds to the Korean context –keeping punk's raw energy while bringing in local themes.

Urban Folk and Indie Ballad

Another key current came from folk and alternative ballads, shaped by Japanese and American singer-songwriters and even traditional Korean music. This side of K-indie is more introspective, emotional, and literary. Bands like Broccoli, You Too? and artists like Standing Egg and Kim Kwang-jin embody a softer sensibility –where "indie" isn't noise, but intimacy and subtlety.

Hip Hop and Alternative Beats

A lot of Korean hip-hop went down a different path. Today it's far more present in K-pop's sound, and it's a mainstream genre in South Korea –less about marginality and more aligned with pop's commercial logic. Still, it's worth noting that many underground DJs and rappers hung around Hongdae in the early days, and some artists are still trying to reclaim the genre's original edge.

The Gentrification of Hongdae and the Present of K-Indie

Like so many scenes, someone with money spotted the opportunity and started buying things up. From around 2010 on, Hongdae began to change: shopping malls, Palermo-Soho-style cafés, tourists everywhere, and rents that became impossible pushed most of these small clubs out. The area turned into a place to shop, take photos, admire pretty buildings, and spend long nights in clubs where the outfit matters more than the music. Legendary venues shut down; others had to move or professionalize to survive.

Today, Hongdae still hosts emerging artists, indie clubs, cultural cafés, record shops, and collaborative spaces. Even if it's more regulated –and more pressured by commercial logic– the scene keeps an experimental spirit. In response to gentrification, new alternative hubs have also emerged in areas like Mangwon, Hapjeong, and Mapo, where small venues are opening and carrying on the underground tradition.

Hongdae's club culture was –and still is– the heart of the movement. It's where the first bands formed, indie's aesthetic identity solidified, and a community took shape that challenged the idea of music as an industrial product. But today, many who want to push back against big corporations that treat art as a profit machine end up finding refuge online.

On Naver forums, KakaoTalk communities, Bandcamp, SoundCloud, and Telegram groups, new networks of emerging artists are forming –pushing back against an overly sweetened sound that doesn't reflect the anxieties of a society exhausted by work demands, or a generation struggling to make sense of what's happening in the world.