Every discipline has its breaking points, where people appear who change the meta and manage to enter the pantheon of masters. Katsuhiro Ōtomo didn’t just create a breaking point: he dropped a nuclear bomb called Akira, which would affect the brains of fans of manga, animation and other related fields in the industry. But, above all, along with other greats of his generation (such as Frank Miller in the West), he is one of those who ended up closing the new social contract of comics, reinforcing the idea that this art can be for adults.

This article aims to bring you closer to his manga work, beyond Akira, so that you can enjoy one of the greatest in universal comics.

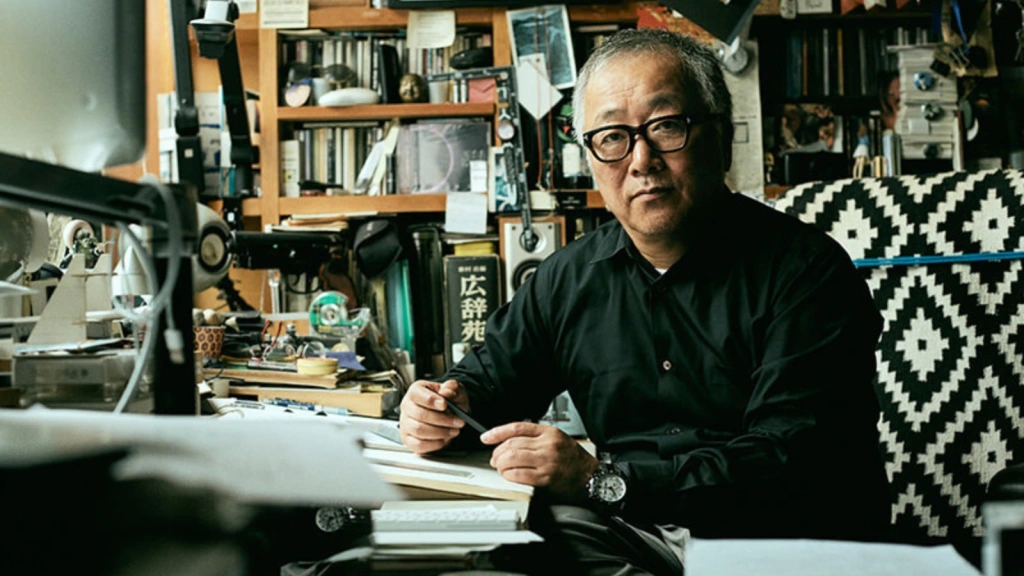

Who is Katsuhiro Ōtomo

Born in 1954 in Miyagi Prefecture, young Ōtomo began his comic book fanaticism as a child reading Osamu Tezuka's Astroboy and works such as Shotaro Ishinomori's Cyborg 009. He decided to start drawing in elementary school, when he read what many consider "the mangaka's bible" or the first book that truly teaches the mysteries of manga: Shotaro Ishinomori's Manga Ka Nyumon, from 1965.

As he grew up, he began to become a fan of cinema, both Japanese and Western, influenced by films such as Easy Rider (1969). In an interview, Ōtomo recounted how many of the films he liked spoke of leaving home to pursue something greater. In 1973, determined to enter the manga business, he moved to Tokyo and that year debuted working for Manga Action magazine.

Between the late 1970s and early 1980s, he refined a unique signature: realism, cities that are characters in themselves, editing vignettes with the flair of a filmmaker, and stories that seek to confront youth and old age, technology and religion, delving into the new traumas of society that he perceived from Japan.

In 1982, this mental cocktail led to the publication of Akira, one of the most influential works in the medium, and in 1988 he directed the film, considered one of the milestones of anime, which gave Japanese animation worldwide visibility.

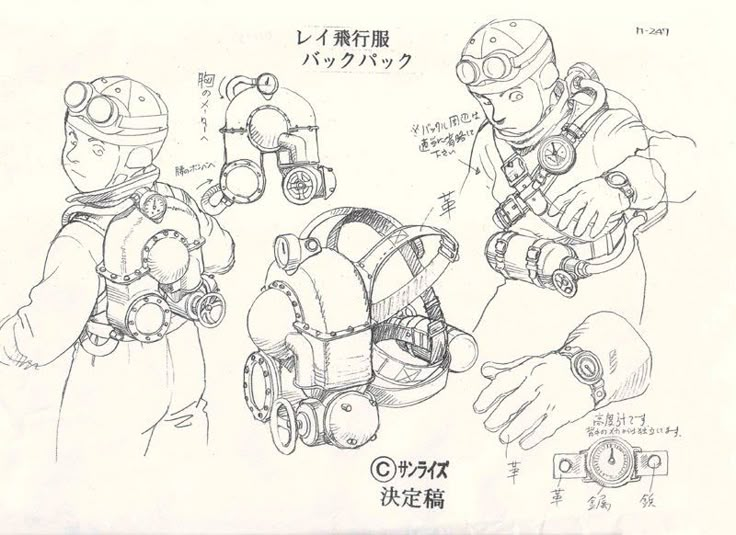

Beyond the manga and the acclaimed Akira, Ōtomo worked on key pieces in anime and film: Roujin Z (1991, script), the live-action World Apartment Horror (1991), the anthology Memories (1995, producer and director of the Cannon Fodder segment), Steamboy (2004), and the ensemble project Short Peace (2013), where he directed the short Combustible.

Ōtomo's work was included in many subsequent manga projects, as well as in other media and genres. To get to know him beyond Akira, let's review three must-read works and a rare piece he published for DC Comics.

Memories (Ōtomo's anthology, with stories from the late 1970s)

With different names depending on the edition and translation, this anthology is like looking through the sketchbook of the master Ōtomo. In its first Spanish edition, published by Norma, we can find ten stories where he condenses his obsessions: Memories (Kanojo no Omoide), Suspended Construction (Kōji Chūshi Sengen), A Farewell to Arms (Buki yo Saraba) or Fireball, among others. Let's highlight two.

In Memories (Kanojo no Omoide), which is the name given to the anthologies generally, a distress signal brings a team of astronauts to a stranded spaceship. Inside is a baroque palace where reality and memory mingle under the influence of an intelligence that lives on board. This haunted house tale in space is the basis for Magnetic Rose (1995), a short film that is part of the anthology Memories (directed by Kōji Morimoto and written by Satoshi Kon), which amplifies the theatrical tone of this story. A must-read.

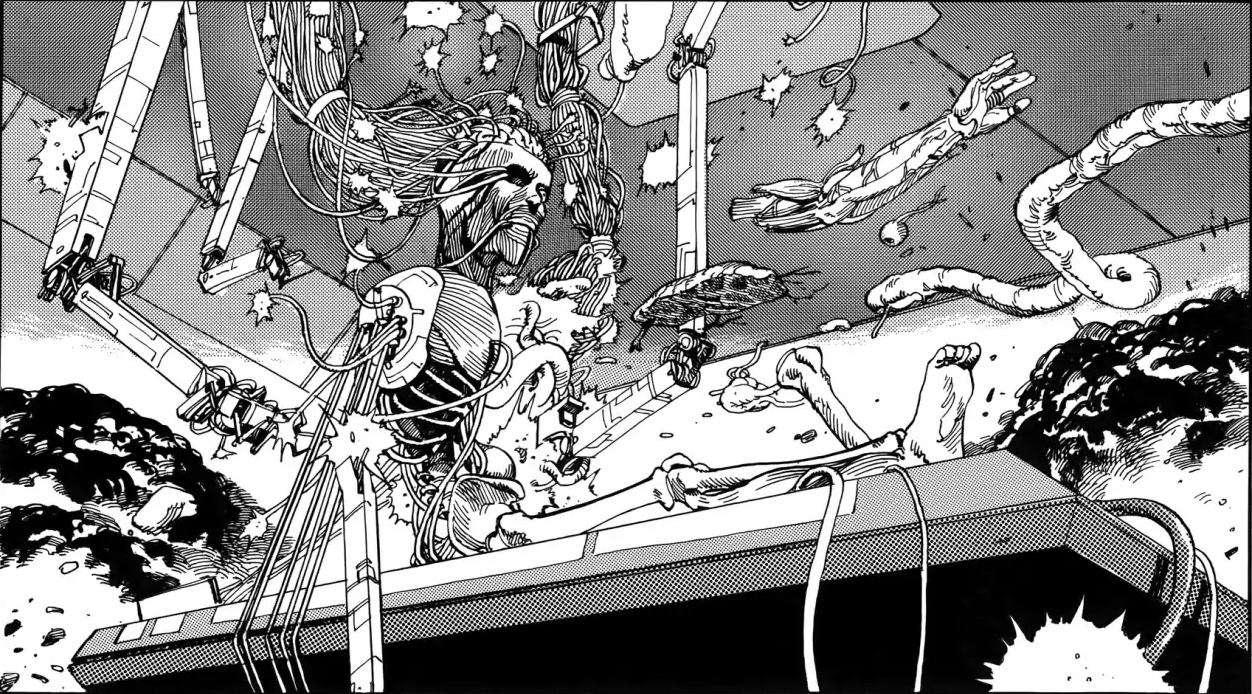

The other story worth highlighting is Fireball, one of his first published works, where we find a "proto-Ōtomo" who begins to lay the foundations for what would eventually become the quintessential cyberpunk tale (Akira). In Fireball, there is a technocratic regime with an AI controlling the city, and a secret project that aims to turn a young man with psychic powers into the ultimate weapon, but a group of rebels will attempt to sabotage the system and its experiments. Biopolitics, military conspiracy, total urban planning, and adolescence as a vital force for changing the world. Ōtomo wasn't satisfied with the story's ending, and the ideas swirled around in his head until he created Akira.

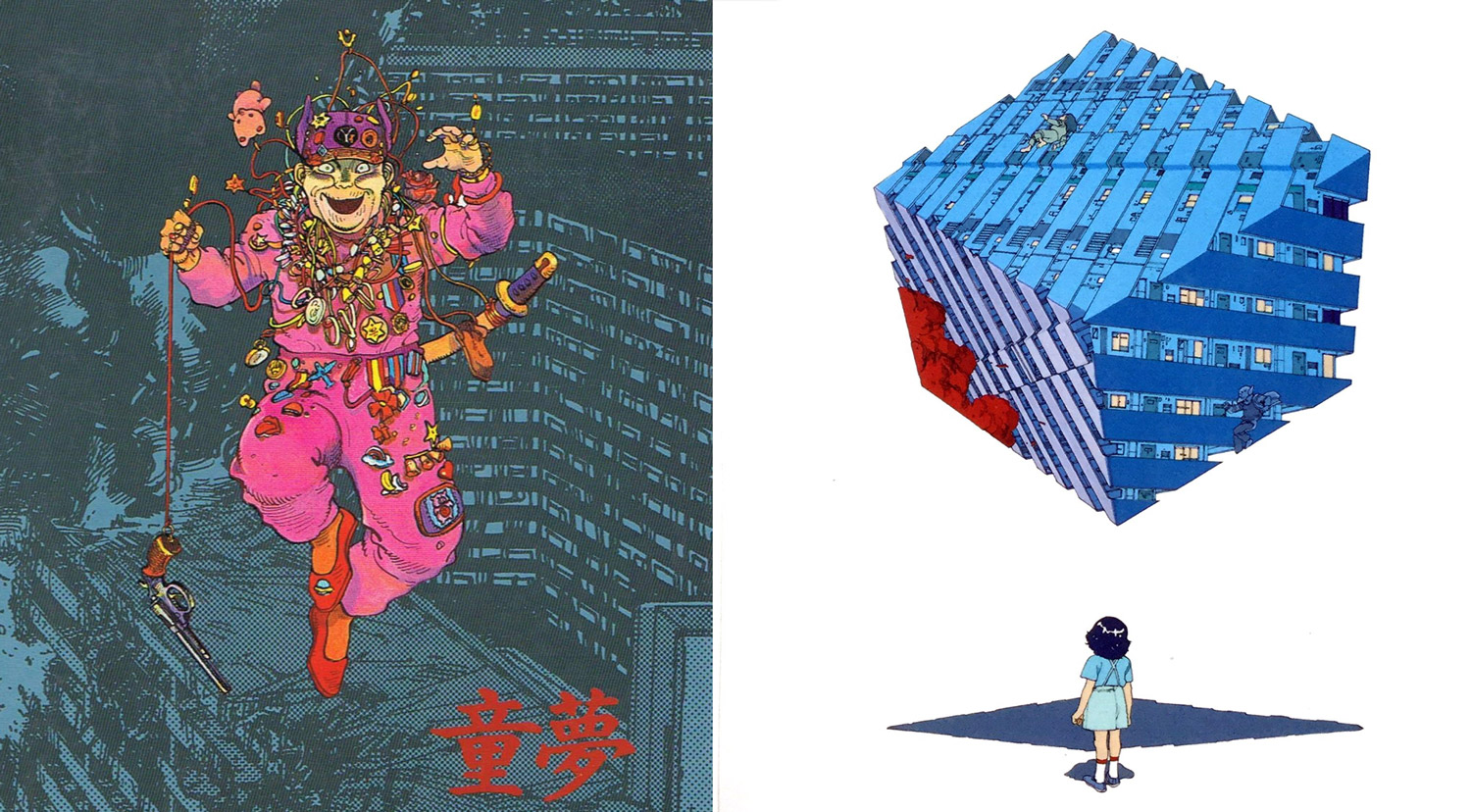

Dōmu: A child's dream (1980 - 1981)

In a large housing complex, strange events begin to occur, followed by unexplained "suicides." The police begin to investigate and realize something isn't right, but it isn't until a girl with psychic powers arrives at the building that the mystery behind these bizarre occurrences begins to unravel.

This supernatural thriller is one of the stories that anticipates the DNA of Akira. Ōtomo once again experiments with characters with powers, influenced by psychic films like Carrie and The Fury, both directed by Brian De Palma, and with buildings resembling public housing complexes similar to those built in post-war Japan, represented as large concrete structures. Ōtomo takes an everyday setting and turns it into a nightmare of hallways. Dōmu is a paranormal tale in a cruel urban setting, ideal for enjoying a 100% Ōtomo story.

The Legend of mother Sarah (1990 - 2004)

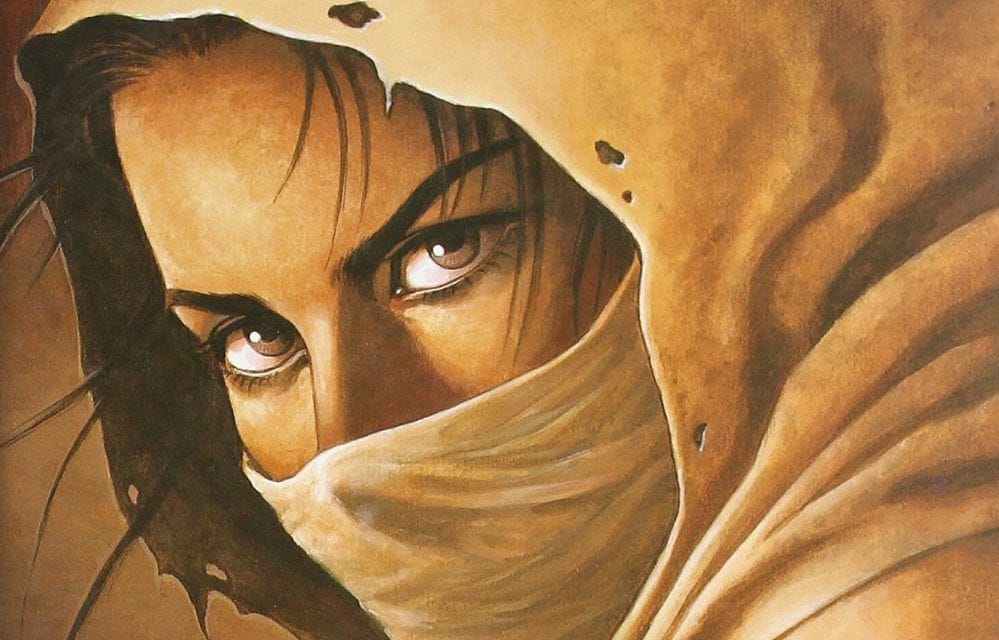

In this future, humans lived in orbital colonies above a destroyed and poisoned Earth. But after a terrorist attack, the colonists are forced to return to their former planet. Now the old new world is fragmented by military dictatorships, criminals, and guerrillas. Amid the chaos, Sarah is separated from her three children and embarks on an odyssey to reunite them. The stories take her through radioactive deserts and industrial labyrinths, having to confront soldiers, traffickers, and fanatics as war shapes humanity's future.

Written by Katsuhiro Ōtomo and drawn by Takumi Nagayasu, The Legend of Mother Sarah is a sci-fi road movie-style story that draws heavily from stories like Mad Max 2 and Hokuto No Ken. It's the idea of a dry, dead future where barely functioning technology coexists with people who become increasingly violent and primitive under those conditions. Here, the focus is on civil resistance to an unjust world and compassion as a radical act.

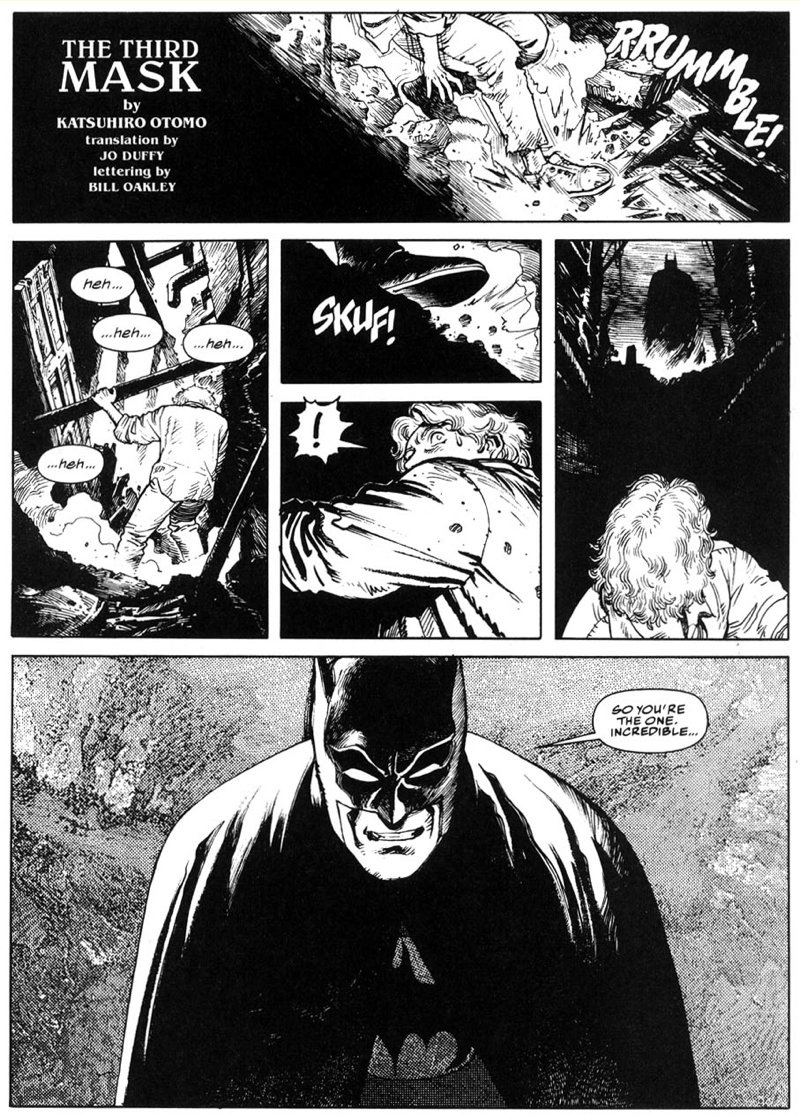

Batman: Black and White: The Third Mask (1996)

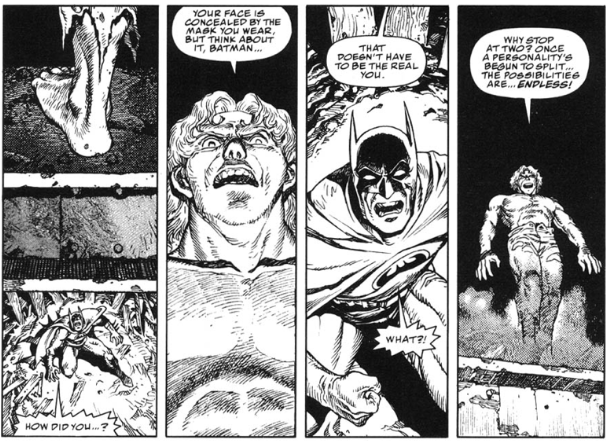

In the early 1990s, DC launched Batman: Black and White, a miniseries of self-contained black-and-white stories. Curated by editor Mark Chiarello, it sought input from writers around the world on the caped crusader. Chiarello brought Ōtomo on board after the international impact of Akira, giving him complete freedom over his story.

In just five pages, Ōtomo destroys Batman. I think he even sets a new record for destroying a character: not even Moore could do it that fast. In this mini-story, Batman faces a serial killer with multiple personalities who shocks Bruce with a line: "Once a personality splits, the possibilities are endless." The detail and love of comics in every panel make this story one of everyone's favorites in the Black and White anthology.

Katsuhiro Ōtomo is among the greatest comic book artists and has influenced thousands of authors. But Ōtomo is also a monster in the world of animation, and his fanaticism for both that discipline and film is what makes him a great storyteller in both media, managing to create vignettes and sequences on paper filled with life. And when you see him directing or working in animation, the same thing happens: you can see those vignettes in motion.