Make: the final frontier. Making is a drive, a passion, a spark. In my case, it’s one of the things that keeps me sane and excited to keep going. Making can be something you do with a specific goal in mind —or just a hobby. When I was a kid, I got a Simpsons book called Rainy Day Fun Book, and this guide/tutorial carries a bit of that same vibe. We’ve already made a fanzine together, and we’ve already made a little game with Bitsy —so why not combine the DIY spirit of indie publishing with the playfulness of a game?

We’re going to prototype a board game and produce it fanzine-style. To do that, I not only started making my own war game —I also talked to people who’ve made their own games, asked for advice, and I’m sharing it with you here.

The Idea, the Concept, and the Real World

You have to find that first spark —some whim or obsession— and then work the concept and playtesting until you reach what the industry calls an MVP (Minimum Viable Product): the simplest version of your idea that actually works. In my case, I started researching anime-based war games like Gundam and stumbled onto a whole scene of Japanese wargames from the ’80s and ’90s I didn’t know existed. With that new info, I got fired up to make my own.

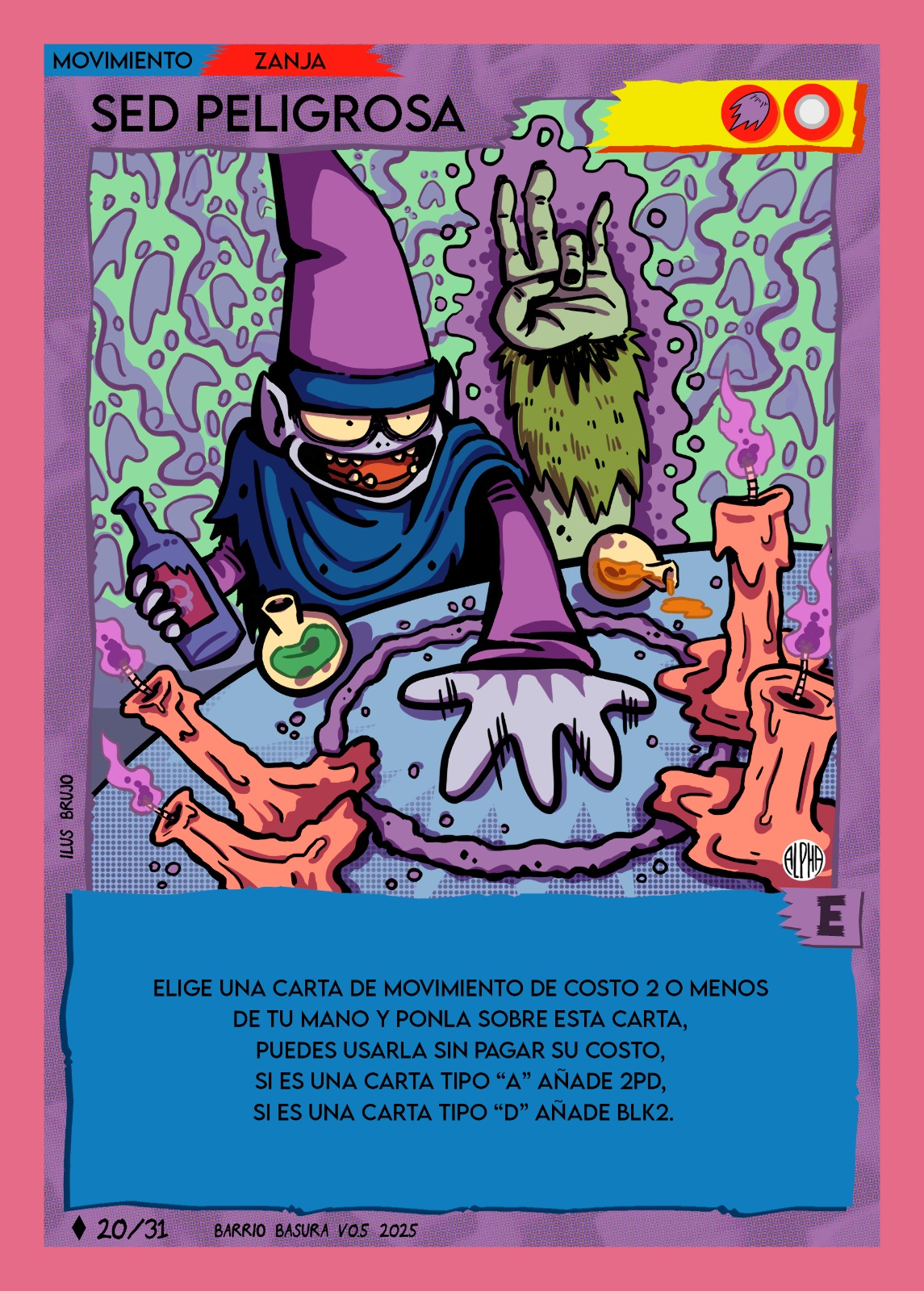

On the other hand, with Barrio Basura (roughly “Trash Neighborhood”), a game that got tested at the 421 Quest event, its creator —El Brujo— already had a card-game system in mind that would emulate fighting games. But the trigger for it was way weirder. In 2021, while vacationing on Argentina’s Atlantic coast, he found a little “hand” from an animal he couldn’t identify, and a character popped into his head —perfect for the game. That was the spark that kicked off the first version.

Your first step might come from a system you came up with, or from a setting you want to wrap around the game —but it has to start somewhere. And since this isn’t a job (at least not yet), make the game you’ve always wanted to play. If you’re into TCGs like Magic: The Gathering or Pokémon, look into the genre: what’s happening right now, and which games are at their peak. I also recommend digging through forums for more underground work —and on platforms like itch.io you’ll find tons of people uploading their projects. Studying the format, collecting references, trying games for inspiration, and understanding the scale we’re working at is crucial. But I have to remind you of something: stealing is wrong.

Unlike El Brujo, my motivation started with the ’80s anime aesthetic of military mecha, and from there I began thinking about the game system. Because I wanted a strong nod to hex-grid wargames, I read rulebooks and watched a bunch of playthroughs. I wrote down mechanics I liked and started tossing ideas onto a sheet of paper. To get it all down, I answered a few guiding questions: What do I want to happen in my game? What’s the simplest way to make that happen? Which mechanics add complexity? How do you win?

Prototyping and Punk Rock

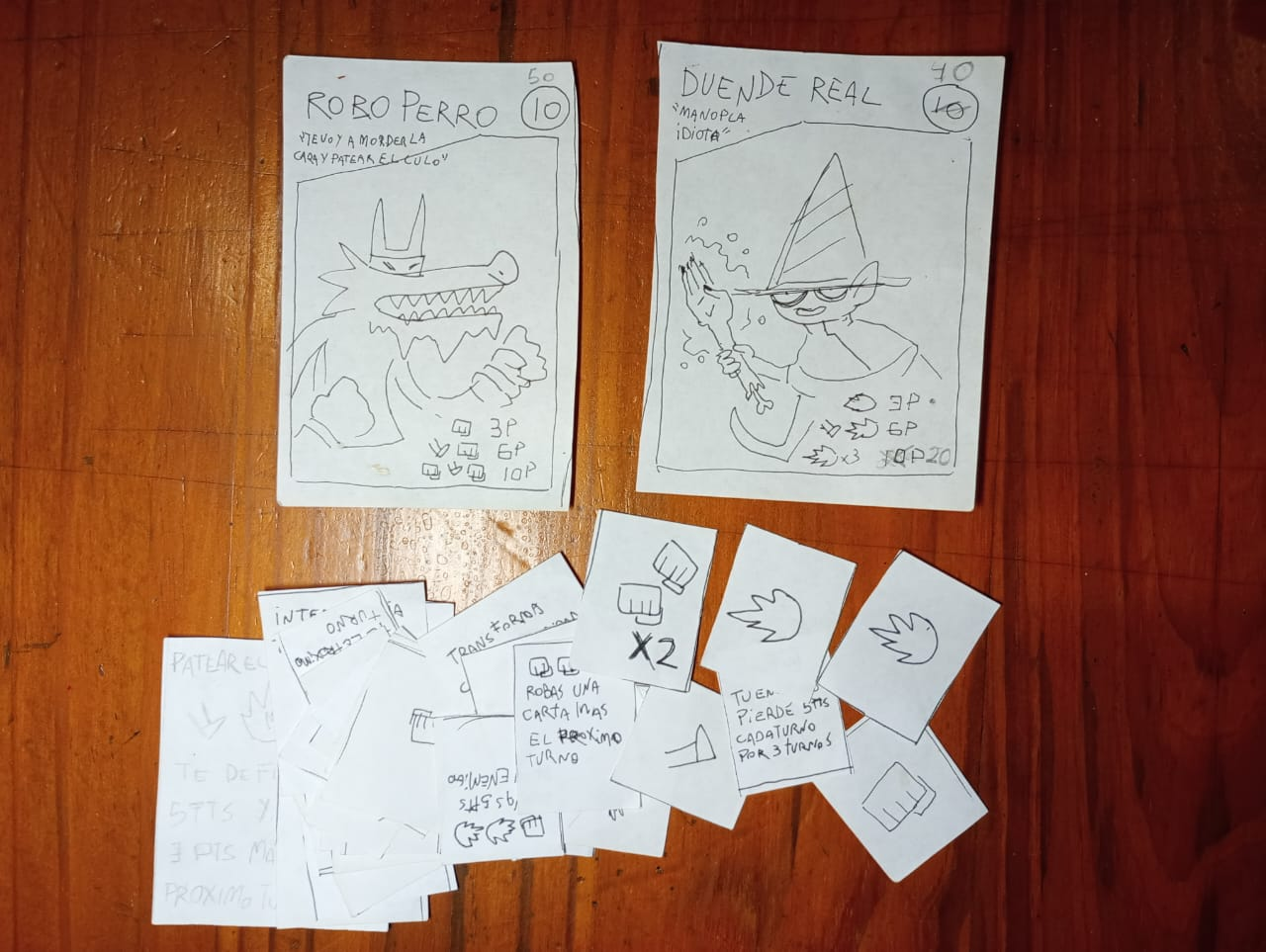

Once you’ve gotten the main idea into some kind of document —personally, I like working with a notebook and pencil, and using spreadsheets on my computer— you can start thinking about the MVP in terms of the basic components you need to playtest. In the case of the wargame I’m prototyping, I needed unit tokens, a map, and —at first— about 12 cards, plus a D20 and D6 so I could test it with two players.

The DIY survival kit says you’ll need paper, pencil, and scissors —plus a few basic supplies. Even if you go digital and print things out, for the physical build you’ll still need paper, pencil, and scissors. Grab references, then sketch a template on paper or in any design tool —just enough to playtest. If it’s a card, make sure there’s space for the key info and the art. If it’s tokens, add whatever labels you need so they communicate what they do —just keep them simple.

This prototype is v1 of your future game. The key is that it’s understandable and doesn’t create unnecessary costs —because this version might not last long. For now, the game lives in your head and in a document, and you may have done a quick mental test or two. What we want is physical pieces you can put on the table and test with two players.

I worked on my wargame first in a notebook. Then I moved the rules into a spreadsheet, and used a design program to build basic templates for testing. I kept the designs very simple and used images from the internet as placeholders. At this stage, anything goes —but if I want to share the game later, I’ll have to replace and refine a lot of that.

Next step: we’ve printed, glued, and cut the components, and we’ve got enough to start playtesting.

Iteration, the Whole Point

Gavriel Quiroga has created games like Sygil: The Mirrored Reality and Hell Knight, plus a new MÖRK BORG module called King Borg —and also the RPG based on the comic by Quique Alcatena and Eduardo Mazzitelli, Acero Líquido. Several of his projects were playtested at 421 Quest. Gavriel emphasizes how important it is to test your game with playtesters who don’t just “play”, but bring creative thinking that challenges your design —so you can see where it’s weak and where it shines.

You’ll often run into situations you didn’t anticipate: sometimes they’re problems to fix, and sometimes they’re happy accidents that lead to a new mechanic or an idea that improves the original design. The point is to test with different people, take notes on their experience, and ask what they thought.

You can start with one group: people with zero experience in a game like the one you’re making, and experienced players you can find at game clubs. Running the game with different kinds of people —who have different relationships with gaming— is really important. And if you already know an “audience” you think might love it, it’s worth creating a dedicated space to test with them too. Everyone can give you feedback you can use.

After a few rounds of testing, you go back to your main document, clean up the ideas the playtests gave you, and start thinking about that MVP —or v2.

V2 and the Road to the Final Version

You’ve tested the game —now you have to decide what to do with what you learned. You’ve got two paths, Choose-Your-Own-Adventure style.

First: if you need to change a lot, the best move is to update your templates and test again. Sometimes you don’t even need to rebuild anything: a rules change doesn’t necessarily affect a token or a card design. You can repeat this step many times, but don’t get stuck —keep moving when you feel confident, and even when you feel blocked.

The other option is that your game mostly works. You might need to tweak a few things, but nothing that forces you to rebuild the entire system from scratch. In that case, you can invest your time and effort into a higher-quality version and a new playtesting kit. With players and components in mind, you can start putting together something that looks better and puts more work into the visual side. It’s still a prototype —and you still need to test— but now it’s more polished, and nicer to show.

This stage can feel like rehearsing forever and never going out to play a show. Break the curse and move forward. This is punk prototyping: we rehearse while we’re already gigging, and we’re not embarrassed by how we sound. I’d rather make things and push ahead than run in circles chasing a perfection our ego will never hand us.

Like in Magic: The Gathering —when in doubt, you attack— here, we move. My wargame has already gone through a couple of tests in its most basic form. It works, the math checks out, and it’s dynamic. Now I need to keep refining the gameplay, then get it back on the table —this time with people I don’t know.

More than anything, this little guide is meant to get you to sit down and make something —something you made yourself, for yourself. If you later want to take it commercial, you can check out my piece on how to sell a video game for a few extra tips. But for now: have fun. And remember —Warhammer and Magic put out products that sometimes feel barely playtested, with impossible rulebooks or interactions that shouldn’t exist. So yeah: you can do better.