It's 1998. Urza's Saga has just been released. The infamous "Combo Winter" is born. The game is so broken that emergency bans are issued to avert catastrophe. You don't know it yet, but many cards from this block will become legends. Gaia's Cradle will climb to around $1,000.

It's 1999. Sixth Edition lands –along with major rules overhaul. The stack appears, perhaps the best invention in Magic: The Gathering after the cards themselves.

It's 2000 –the turn of the millennium– and the Invasion block lands. The saga of the Weatherlight, the Predator, Volrath, Gerrard, Urza, and Karn comes to a close. No Magic storyline will reach this dramatic pitch again.

It's 2001. Argentina's convertibility –and the economy– collapse in on themselves. Odyssey, Torment, Judgment are released. They feel like a premonition.

It's 2003. Néstor Kirchner takes with 22% of the vote. Days earlier, Scourge –the last set with the old frame– hit the shelves. It's the first time you feel something has changed in Magic, even though you haven't bought a single card in a year. You simply can't afford to.

It's 2025. Magic announces a new Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles set. You scroll through spoilers on your phone on the way home after a long day. Your wife texts: pick up some vegetables. You open the door and a child with your face hugs you. You walk the dog. You order pizza. Javier Milei, the president, has just won another election. You're 40.

In one of the thousand WhatsApp groups you're in, someone suggests a draft. You say yes. It's this Saturday. Your kid's end-of-year performance is that day. "I'll join the next one."

1995 - 2003

Several of us feel a strong nostalgia for what we might call Magic's classic era. Whether it was truly the best is debatable –and whether it rivals Alpha, Beta, and Unlimited in iconic status at the card level. But it was unquestionably unique, thanks to a confluence of not-so-minor factors.

In 1997, with Tempest, the game reached a new level of complexity, synergy, and narrative. That watershed block also marked the arrival of legendary designer Mark Rosewater to the design team. Exodus introduced rarity pips. The arc of the Weatherlight crew and the looming Phyrexian invasion gave the game a lore of its own that was never quite surpassed and became inseparable from that era. Even if Magic later shifted toward an IP-agnostic model –mechanically functional but flavor-agnostic–those cards are steeped in the narrative that began with the Brothers' War between Urza and Mishra in Antiquities. See a Tolarian Academy, a Yawgmoth's Will, or Mirri, and it simply feels "more Magic" than a My Little Pony crossover card.

For me, 2000 and 2001 were the years when Magic –like cybercafés– became a lingua franca for us kids. Tournaments in the Villa del Parque galleries, at Beiró & Lope de Vega (DGL), or in Belgrano (at El Señor de los Anillos and Armageddon) felt mythical: the turnout (my first had 50–60 players), the decks in the room (ultra-aggro White Weenie, Trix, Necropotence shells), and the characters who inhabited them.

Ask any forty-something and you'll hear the same story, with slight changes of venue: the Caballito mall, a neighborhood gallery, the Abasto courtyard. It was Argentina's teenage golden age of Magic –part of the zeitgeist. Magic, MTV, Limp Bizkit –all tangled together.

Finally, ESPN's Pro Tour coverage, dominated by Jon Finkel and the German juggernaut Kai Budde, closed the aspirational loop. When someone questioned why I spent money on cards, I'd always drop the same (never-verified) stat: "The final of the biggest tournament pays $5,000." Instant respect.

Throughout these years, Magic has undergone many transformations. It has become a global platform for Hasbro to monetize and connect with other intellectual properties. The game is so robust that you can layer almost any skin onto it and it still works. There's little connection between mechanics and lore anymore. The cultural climate of our golden years is largely gone. But the cards remain.

Casual and Competitive

As we’ve explained before, Magic’s strength lies in (1) its undeniably social nature and (2) the sheer number of player-created formats that kept it afloat even when the company itself hadn’t quite figured out where the scene was headed.

Broadly, Magic is played with either a competitive or a casual mindset. Competitive play prioritizes results and demands time: regular store play, metagame awareness, tracking new releases and major event results, and knowing which cards offer an edge. It’s time-consuming — even exhausting — so the scene skews toward intrinsically motivated players.

Casual play is looser: you jam games with friends when you can, with your own cards/collection, and the goal is simply to have fun. From that space, formats can grow — sometimes into competitive ecosystems — as with Pauper or Commander. Premodern is the newest of these late, player-made formats.

Standard, Type 1, Legacy, Type 2

Today, competitive Magic is split into formats such as Standard (a rotating pool of the most recent sets), Pioneer, Modern, Legacy (nearly everything, with a short ban list), and Vintage (everything, with some cards restricted). Tension has always existed between “play the new stuff” and “play it all.” Before this, there were Type 1 and Type 2.

Mark Rosewater said in his defunct blog (which changed URLs so much that it is no longer possible to find it):

Magic would have two formats, known as Type 1 and Type 2. Type 1 would maintain the status quo: any card could be used in it, but respecting the list of prohibited and restricted cards. Type 2 would limit the reservation of letters to those published in the two most recent years. The letters would enter and exit the format, since this would only cover the last two years. When it was announced, Type 2 was poorly received among players. "How come there is a format where I won't be able to use all my cards?".

At first, Type 1 was the undisputed king, while Type 2 was seen as a curious novelty. However, as time went by and more expansions were released, new players began to have a hard time getting cards from old collections, so they became more attracted to Type 2. There were still people who preferred Type 1 and, although Type 2 continued to gain followers, Type 1 had its unconditional fans.

And now, let's move forward a little in time. The difference between Type 1 and Type 2 grew with each passing year. Then a group of players began to emerge who were looking for a broader format than Type 2, but without reaching the effectiveness levels of Type 1 (or requiring access to some cards that were already very difficult to obtain). The solution was to create a new format called Type 1.5, which used the entire pool of Type 1 cards, only the entire list of banned and restricted cards was banned.

Type 1 changed its name several times, until it was finally named Vintage. Type 2 obviously became Standard. Type 1.5 underwent a change in 2004: instead of directly banning Vintage's entire list of banned and restricted cards, the format got its own ban list, because there were cards that, although not problematic in Vintage, did cause problems in Type 1.5. After that, the format became known as Legacy.

Type 1.5 —“Extended,” as we knew it— was the era’s most popular format: huge deck variety, head-to-head. Most new stuff (Mercadian Masques–Invasion) and the old up through Revised. Watching multiple playsets of dual lands was bliss. I saw the wildest matches there — Mono-Black discard with The Rack and Cursed Scroll, Necropotence (reprinted in 5th), Tinker, Turbo Stompy (oh, the Wire), White Weenie, Rebels. All-time classics.

And yet the march of new formats swept the field. The card frame changed, planeswalkers arrived, Mirrodin dawned, Nicol Bolas returned. Was there no way to reclaim that lost glory?

Premodern

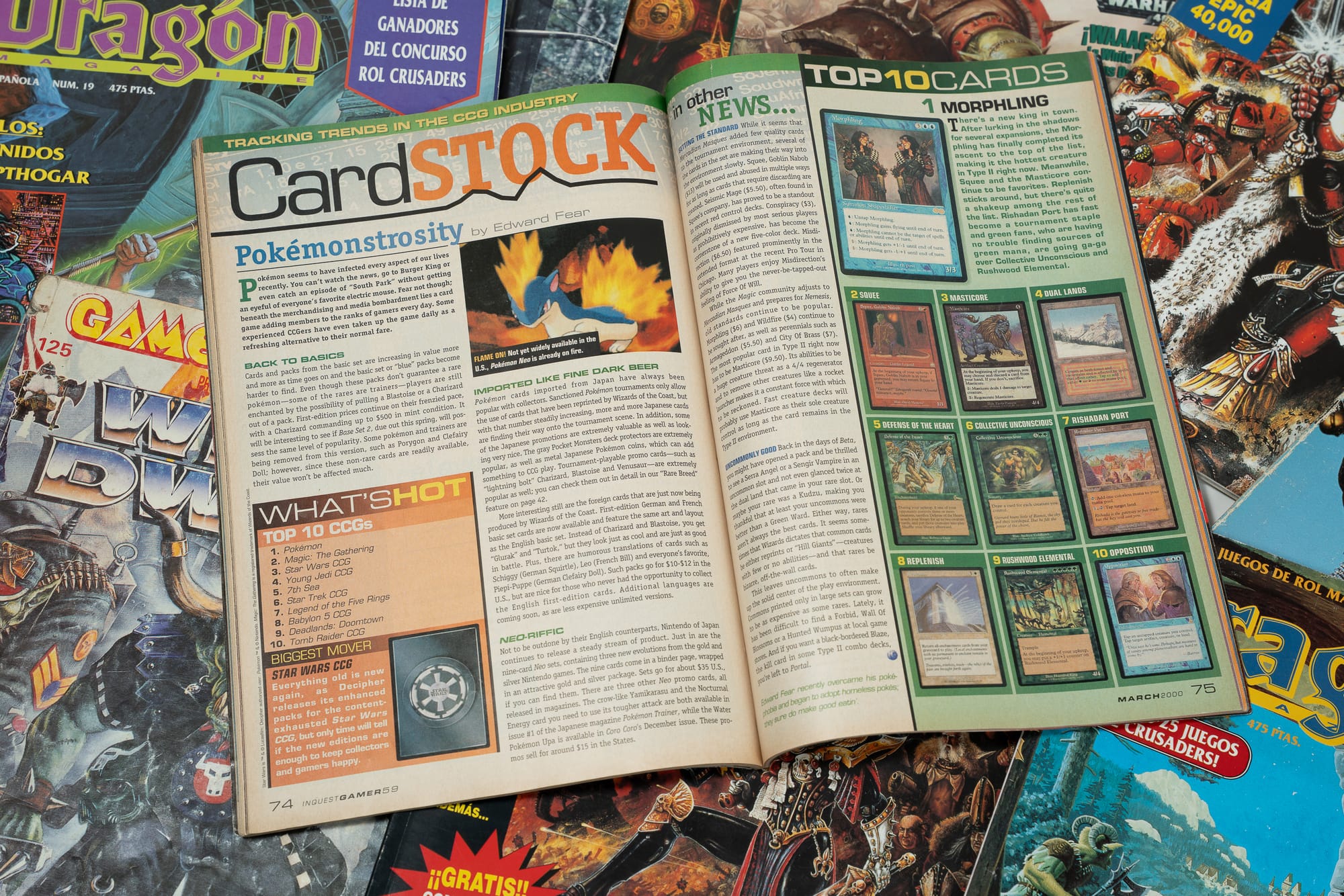

Out of that impulse came Premodern — the newest success in the lineage of community-made formats. Created in 2012 by Martin Berlin, it set out to replay the old-frame golden era, just before innovations changed Magic forever. The name says it all: cards chronologically prior to Modern.

There’s an official site with a ban list — yes, Force of Will is banned — aimed at keeping the metagame diverse. In Argentina, after a tentative start, Premodern has become one of the big formats. Why? First, many of us already owned a chunk of the card pool — it was a matter of dusting off boxes. In my case, I dug out my Replenish deck from a friend’s place.

As Martín “Rulo” Domínguez said after winning a major event, Premodern lets players who can’t grind hours still stay in the hobby. With a fixed, familiar pool, there’s little churn: strategies rotate and a few cards trend into the meta, but there isn’t a constant pressure to study or buy the latest releases.

For many of us, it’s also a first chance to play cards like Replenish, Morphling, Recurring Nightmare, or Survival of the Fittest legally and in events. And the Argentine scene is thriving: Friday Night Magic at Bazaar (Caseros), national championships — even a South American. Most major Buenos Aires stores host Premodern. There are tournaments in Ushuaia. Not bad for a format that barely existed a few years ago. Lists are easy to follow here.

My way in was simple. I hadn’t played Magic with my friend Patricio in years; he had a pile of humble Elves, and my Replenish deck ran him over every time. Since he’s one of the few friends from the golden years, I wanted two good, complete period decks so we could throw down anytime. I pulled two 2000 Standard lists: Rebels with Linn Sivvi and a slightly soft Fires. Both Top 8’d Pro Tour Chicago 2000. Having them built for pick-up games with Pato felt perfect — a way to return to Magic’s best part: friends, lore, and pretending to be mages slinging spells.

In short, Premodern is a window for those of us who can still play — but at an adult pace — without the constant pressure of spoilers, new sets, or shifting metas. It’s a great slice of a wonderful Magic era: a fully formed world design and a distinctive art style that still resonates with those who lived it.

Premodern, then, is a refuge for the noble traits that made this game great — a way to play that isn’t exhausting amid the whirlwind of consumption.

EN

EN