8 a.m. on Sunday, January 18, 2015. Federal prosecutor Alberto Nisman’s computer. New tab. Google. “Psychedelia”. Search.

Psychedelia is many things: a scientific field, a component of ancient rites, and a creative genre that helped build entire cultural industries. It’s also the last thing searched on Nisman’s computer —presumably by Nisman himself. “Psychedelia”, plain and simple. A concept so normalized, and yet so dynamic, that a 51-year-old federal judiciary official with 26 years in the system would need to Google it.

What Psychedelia Is

The word “psychedelia” roughly means “manifestation of the soul”, from the Greek combo psykhē (soul) + dēloun (to reveal, to make visible). The term was coined by the English psychologist Humphry Osmond in the mid-1950s, in an exchange with novelist and philosopher Aldous Huxley. The author of Brave New World (1932), also British, had published The Doors of Perception in 1954 and, by 1956–57, was hitting up “Doc” Osmond for mescaline. All of this, notably, almost two decades after Albert Hofmann first synthesized LSD in 1938.

LSD and psychedelia go hand in hand. Lysergic acid diethylamide—LSD— is one of the most powerful and effective catalysts for psychedelic experience ever created. And I emphasize created because there are hundreds of natural sources of psychedelia, some used ceremonially and for visionary pursuit for thousands of years —complete with mushroom paintings dating back 7,000 to 9,000 years.

There’s psilocybin, mescaline, ayahuasca, peyote, Salvia divinorum, morning glory, angel’s trumpet, Amanita muscaria, and hundreds of plant species and compounds with the ability to make us see, feel, and hear things that aren’t there —to make us perceive time and space in ways that are not only unconventional, but at times truly uncanny.

Psychedelia is, then, a technical and scientific domain: a family of psychoactive substances, some synthetic and many natural, studied by hard-science disciplines like neuropharmacology.

Psychedelia is also a set of ancestral traditions: a channel for integration into communities through initiation rites or collective ceremonial use —and a way in which a community’s destiny can be decided through the mediation of shamanic figures.

And psychedelia is also a cultural movement —or the “drugged arm” of the hippie movement— which, carried especially by music, opened a creative tradition across the arts, coined an aesthetic, proposed a new “code of coexistence”, and became a kind of shibboleth among outsiders.

In short, psychedelia is science, religion, and art: an overlap of transcendence-seeking modes. Odds are, you’ll be seduced through at least one of those three doors.

A Starter “Psy-List”

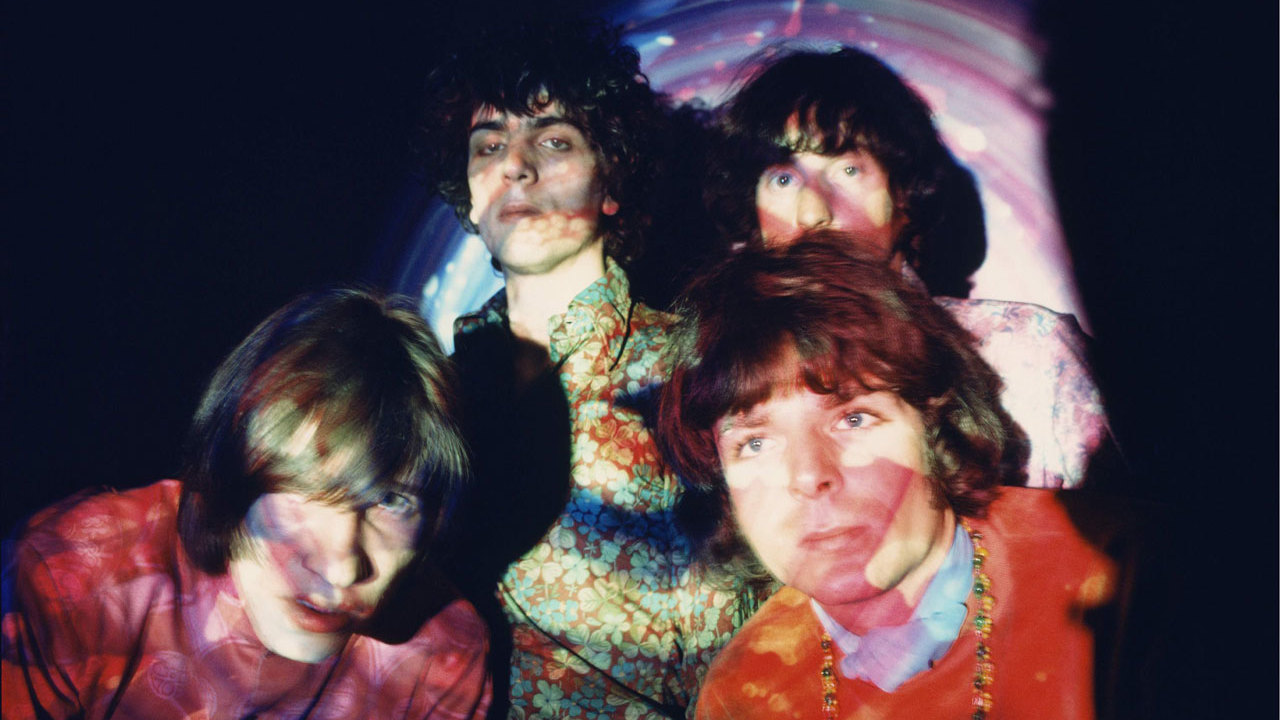

Psychedelic music, as a recognizable segment, broke through around 1965–66 with The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Beach Boys, 13th Floor Elevators, Donovan, Love, The Velvet Underground, The Who, The Zombies, The Doors, and even The Byrds or The Mamas & the Papas.

A more radically psychedelic tradition opened almost immediately with Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and Pink Floyd —and over the decades it came to include The Flaming Lips, Tame Impala, and Wilco; Amazonian psychedelic cumbia; Tuareg guitarists from Niger; the hardest psytrance on the scene; King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard’s live shows; the covers Geese pulls off; the mischief The Avalanches, Aphex Twin, and The Chemical Brothers got up to; Tool’s head-spinning accelerationism; and irresistible tracks by MGMT.

In Argentina, psychedelia began its lineage with Pescado Rabioso, La Cofradía de la Flor Solar, Los Abuelos de la Nada, and Color Humano. Around the turn of the century it shone in bands like Babasonicos and Los Natas, and during the indie boom it added still-missed specimens like Morbo y Mambo. Today, on an increasingly larger scale, Winona Riders stands out as a reference for vernacular psychedelia —full of dissonance and marathon-length shows.

“I Like It If It Makes You Dizzy”

Truthfully, we’ve all had psychedelic experiences —those of us who’ve used drugs and those who haven’t. Yes, kids too, from a very early age. I’m referring to a form of altered consciousness so widespread over time it may well be universal: getting dizzy on purpose. It contains almost every element people commonly use to define the scope of the psychedelic: a gap with “reality”, discomfort in your own body, sensory distortion, a few physical-chemical reactions, flashes in your vision.

It’s striking how we savor that feeling in childhood —spinning with arms outstretched, then moving on to the rotating carousel in any playground, and finally going hardcore when the samba ride shows up, just as you’re entering pre-adolescence.

And it’s a path you keep walking as an adult, with even dumber dizziness games —like spinning 360 degrees with your forehead pressed to a baseball bat. And then come the new “administration methods” that kick in after 18, whether because you’ve reached legal age or simply have money in your pocket: alcohol as “dizziness by the sip”, weed as “dizziness by the hit,” and the worthy psychedelic drugs as “super-dizziness”.

And I’m fully on board with weed —I love it— but cannabis is not formally part of psychedelia. Not because it can’t alter perception, but because it typically doesn’t produce the kind of vivid, visionary hallucinations associated with classic psychedelics: visions, apparitions, contact with some “alternative reality” where things feel real and lived even if they aren’t happening in consensus reality. Cannabis doesn’t usually do that, much less provide an entheogenic experience —often ceremonial— where those visions orbit the presence of some entity (spectral, elemental) that “speaks” to that soul being revealed and delivers a message. And yet, even if it’s not formal, there’s no question that culturally cannabis belongs in the psychedelic starter pack —as the lowest stage of the ladder.

What Psychedelia Is For Today

With 70 years of tradition as a cultural movement, psychedelia today is not only an aesthetic, a sound, or even an excuse to use drugs. In a way, psychedelia can function as a personal attention-shaping strategy.

The rise of microdosing —and the wider access to psychedelic mushrooms— is a clear indicator, comparable to other waves of drug trends such as high-end cannabis products like Moon Rocks, rosin, or high-THC gummies. Psychedelia is, of course, also a market category, often operated by motherfuckers with no magic.

In a world in constant technological evolution —and warped by psyops and psychopathic and/or schizoid narratives— psychedelia can become a lane for metacognition, a way of pedaling metaperception. It isn’t something you “train”. In fact, those who tried to go all-in on psychedelic training often ended up unable to make it back to “this side”.

You don’t train it, I mean —but it trains you to see the threads in things. It helps dissolve, or at least lower the volume of your triggers (fear, ego/status, even FOMO). And in that sense it becomes a path of reconnection —of rewiring— back into sensory experience, away from the keyboard.