What if, overnight, a computer “operating in the multiverse” could put the world’s most secure systems in check? A question that sounded like science fiction just a few years ago is now everywhere—headlines, social media, and deep-nerd forums.

A few milestones. As part of the centennial spotlight on quantum theory, the United Nations General Assembly designated 2025 as the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology. That same year, the Nobel Prize in Physics went to a group of researchers for decisive advances in quantum computing. And in 2025 alone, nearly $4 billion flowed into the field—public funding led by the United States, China, and the European Union, with tech giants like Google, IBM, Intel, and NVIDIA driving private investment.

With growth this steep—roughly doubling year over year—it’s no surprise conspiracy theories have multiplied, predicting an imminent collapse once quantum computers hit a supposed tipping point. And you’re still wondering what the hell a quantum computer even is.

What Is Quantum Computing?

Quantum theory was developed in the early 20th century, and many everyday devices already rely on quantum effects. Still, none of those effects are directly observable to our senses.

Why? Because quantum theory says matter at microscopic (atomic) scales behaves radically differently from what we’re used to at macroscopic scales. In the micro-world, a particle doesn’t trace a single path like a billiard ball—or a planet orbiting the Sun. Instead, it can explore many possible paths at once, and its evolution is determined by combining those possibilities.

In pop culture, that idea sits behind the multiverse concept (think the Marvel Cinematic Universe, or Everything Everywhere All at Once), where multiple timelines can interact. But one of the earliest multiverse metaphors arguably comes from Jorge Luis Borges: in “The Garden of Forking Paths”, he describes a labyrinth where all possible realities happen at once.

Another classic analogy is Schrödinger’s cat: put a cat in a box with a mechanism that releases food—or poison—depending on whether a subatomic particle decays. In principle, the particle’s quantum behavior would scale up to the macro world (the cat). The result is a superposition: alive and dead at the same time.

Here comes one of quantum physics’ apparent paradoxes: open the box to check the cat, and you’ll see it alive or dead—one of the two. In other words, measurement by an external observer disturbs the mixed state and forces it to “choose” one of the possible stories. That’s key to how quantum computers work.

To Bit Or Not To Bit

Let’s move to the basic unit of quantum computing: the qubit. In a classical computer, information is represented as bits that take the value 0 or 1. Physically, transistors implement this by being on (1) or off (0). Computation is then a sequence of logical operations on bits that produces new information—for example, adding two numbers.

Like Schrödinger’s cat, a qubit can take two states (again, 0 and 1), but quantum behavior allows it to exist in a superposition of both at once. In that sense, it’s a non-binary bit.

A system of qubits can represent far more information than its classical equivalent, because it encodes information about every possible 0/1 sequence. Concretely, representing the state of N qubits would require on the order of 2^N classical bits. For example, simulating 50 qubits would take roughly 140 terabytes of classical memory. That’s why a relatively small number of qubits can, in principle, outstrip the world’s most powerful classical computers.

But there’s a catch: as with the cat, to extract information you have to measure each qubit’s state (0 or 1). Out of millions of possible combinations, only one becomes accessible—and the outcome is fundamentally probabilistic. In quantum slang, the system goes from a superposed or entangled state to a collapsed, definite state. We only ever access one of the possible stories in this garden of forking qubits.

Still, all is not lost: there are ways to exploit entanglement even if you only ever read out a single result. The trick is to design algorithms—again, sequences of operations on qubits—that amplify the probability of the desired outcome over the many undesired ones. Too abstract? Let’s break it down.

A quantum algorithm consists of three stages:

- Preparation: Each qubit is initialized in a known state, 0 or 1 (i.e., not in superposition).

- Propagation: Logical operations make qubits interact and become entangled. This is where the computation happens.

- Measurement: The system is measured (it collapses) and the result is probabilistic. Unlike a classical algorithm, a quantum algorithm typically must be run many times to build statistics; a single run is rarely useful.

Now for an example: Grover’s algorithm.

Suppose you want to find a record in a database that matches a specific attribute—for instance, in a database of people, the one with a particular ID number. A classical computer checks entries one by one until it finds a match. The work scales linearly with the database size: double the records, and the search takes roughly twice as long.

A quantum computer can, in a sense, “search all rows at once” by creating a suitable superposition. But if you stop there, each measurement gives you just one outcome, and you’d have to repeat the process many times—so you’re back where you started. Grover’s key move is to amplify the probability of measuring the correct answer (e.g., the index of the target record), giving a real speedup over classical search.

I’m More Worried About Piranhas

Presented like this, Grover’s algorithm isn’t exactly thrilling outside a hardcore-nerd audience. But what if, instead of a database, you think about brute-forcing a password? It’s the same structure: without prior information, a classical computer must try passwords one by one until it hits the right one. Grover can cut that search complexity significantly—and that’s where much of the quantum hype comes from.

While quantum computing has well-intentioned applications—like speeding up the discovery of new drugs—the main push behind the technology is cryptography.

Most computer-security systems rely on mathematical problems that even the best existing computers couldn’t solve in thousands of years—especially the factorization of very large numbers. If a quantum algorithm (for example, Shor’s algorithm) overcame that barrier, it could trigger a collapse of many data-security systems, including banking information and sensitive national-security data held by government agencies.

Another technology that could face serious pressure is blockchain, which underpins major cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. If a sufficiently powerful quantum computer could cheaply break the cryptographic assumptions these systems rely on, key parts of their security model would need to change fast.

Waiting For Q-Day

The day this feat is achieved is often called Q-Day. It fuels thousands of speculative theories from futurists, conspiracy types, and assorted weirdos: some say it’s near, others warn China will get there first, and skeptics insist it simply won’t happen.

Either way, the evidence behind each theory is shaky enough that public and private institutions keep investing millions—just in case. Because what if God does exist, and someone else gets to “touch the sky” first?

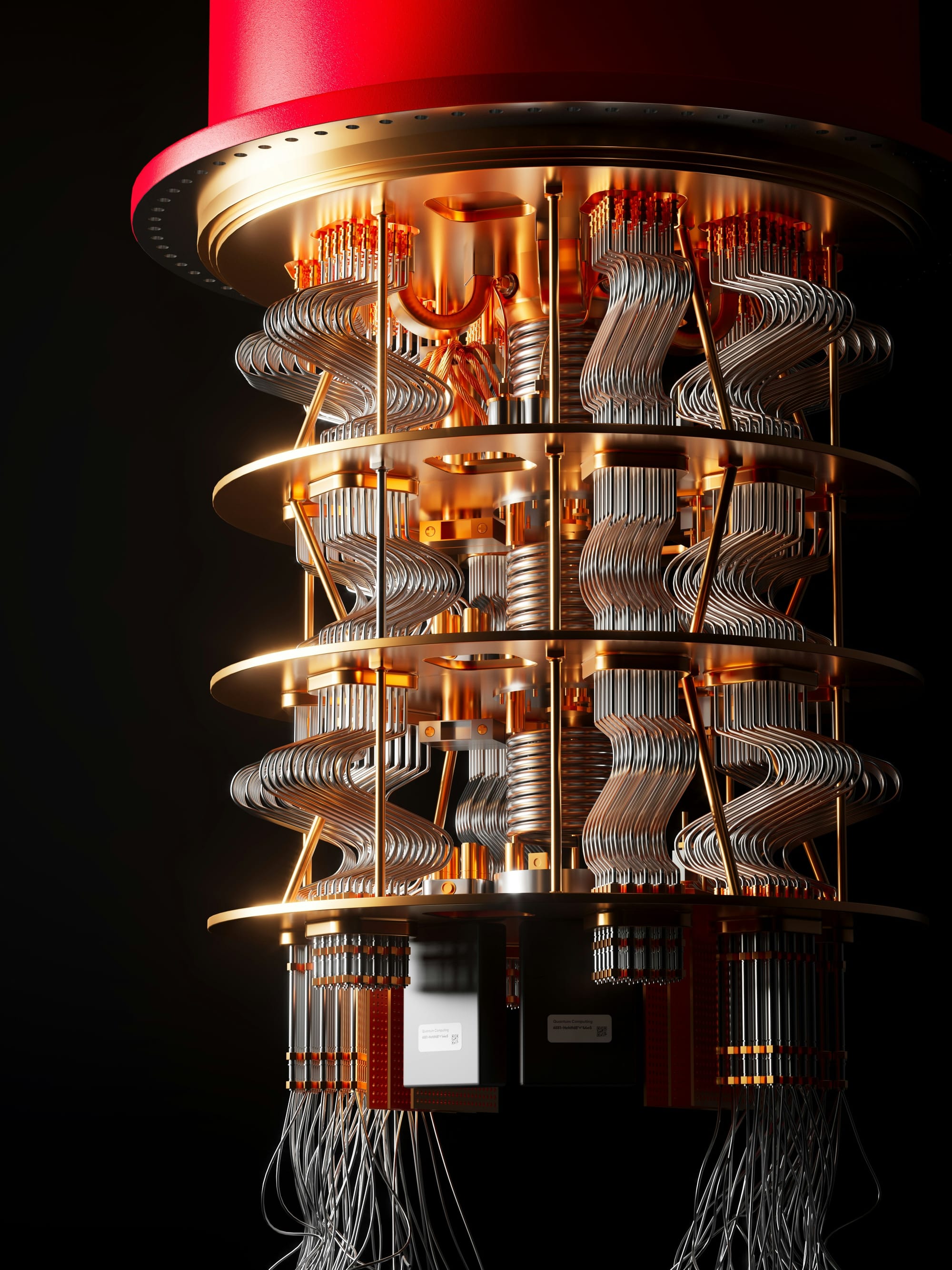

In Argentina, several groups have made major strides in quantum tech. In 2019, physicists at CONICET’s Cold Ions and Atoms Laboratory managed to trap and manipulate a single atom in an ion trap—one possible route to building qubits, and a powerful platform for studying quantum information. Meanwhile, researchers at CNEA’s Bariloche Atomic Center are developing superconducting qubits (the most widely used approach today) as part of the QUANTEC project.

But these initiatives are also feeling the impact of sweeping cuts to scientific funding under the current national government. Meanwhile, China keeps moving fast: this year it announced 105-qubit machines, along with major results in quantum teleportation.

Beyond the big promises, quantum hype is unfolding in an era where speculative bubbles are increasingly common. Today you can invest in virtual land, lunar plots, or memecoins—often for the sole purpose of waiting for the price to rise and selling for a profit. Quantum computing is now part of that same maelstrom, which is why some people wonder whether the whole thing is just another pyramid-scheme story headed nowhere.

Either way, quantum computers are real—and they’re likely to play an increasingly central role in future technology. Time will tell whether these advances spark a new computing revolution or remain mostly academic, and whether today’s massive investments deliver on their promised miracles—or fade into yet another bubble.