The wind blows where it whishes, and you hear its sound,

but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes.

(John 3:8)

One

Some years have gentle curves that Jonah, my partner, and I can move through without paying too much attention —like now, with our feet in the water, tracing the outline of the Golfo Nuevo coastline in the south of our country. Other years hit us with sharper turns, like 2022, which was brutal. Because in the final accounting, in the “debit” column, we wrote a friend’s name. And in the “credit” column, we capitalized pain. We lost Karina Vismara —and in exchange, we gained mourning. Sadness became an inheritance we would rather not have had.

And yet, three years after she died, here we are: counting pain. But more than anything, wanting to tell her. She would have turned 35 on January 7. And her first LP, Casa del viento, will mark ten years since its first live presentation this April.

The truth is, I’ve known for a long time that I wanted to put together a few farewell lines that would inscribe her —once, a thousand times, as many as it took— into Argentina’s musical memory. To honor the gift of having witnessed her search, her uncommon commitment to her own talent, her precise power —surgical yet felt— every time she strapped on a guitar. Until now I hadn’t been able to say much. No written lament, no paragraph that could restore something concrete about her.

But in the privacy of my diary, a month or so after she died, I wrote down a few impressions. They wander the way personal notes do. At times, they say more about others than about her. Now they give me a little push, helping me underline her rightful place in that memory —one I’m asking, today, to invoke her, to listen to her, to please keep her present.

Two

Karina Vismara died on August 10, 2022, at 31, due to kidney failure. A few months earlier, she had been diagnosed with breast cancer. And even though she spent her last two weeks in a hospital bed that promised no improvement, her death was unexpected. No one around her wanted to imagine anything but her recovery. And I’ll even admit that, if I ever hoped for anything for Karina, it was that she’d break through.

A vague and too-generic wish, sure —but in my grayscale-less longing it meant an audience large enough that, by paying for her music on records and at shows, she could cover rent with ease and devote herself exclusively to what she did best. In short: I waited for a whole fable of musical consecration. It didn’t happen.

As long as her body allowed it, she taught English. My mom was her student and loved spending afternoons with her —an excuse to put on a kettle and eat something sweet while they talked endlessly about The Beatles. Karina trained as a musician in England at the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, and Paul McCartney himself handed her diploma to her at graduation. My mom told that story to anyone who would listen, proud to show off her English teacher’s brush with legend.

At one point, Kari also worked the bar at Centro Cultural Richards, thanks to Paco Gallardo —another early adopter and champion of her music through his label, Exiles.

But I can’t judge that setup as an obstacle to making music. Karina found a way to record albums, pay for mixes, print flyers, play solo, play with a band, book and produce shows, put out CDs, hustle a bit of press, land a track on a damn Spotify playlist, join cycles and showcases, keep tours going, try different genres, play festivals, appear on compilations, and shoot videos. She was remarkably skilled at the DIY grind.

In other words, Karina cultivated —allow me to plug in a De Certeau quote here— an art of living in someone else’s terrain, participating actively in the local scene with more or less independence from the mainstream. A fair number of people knew her. I just wish everyone had listened to her, for many more years.

Three

On the morning of September 26, 2022, I wrote in my diary:

We went to say goodbye to Sonia and César, Kari’s parents. On Wednesday they were heading back to Balcarce, after a month and a half wrapping up Karina’s things. Sonia is super neat and organized. César has a cigarette in his hand all the time. They’d taken care to leave the walls and the paint of the little house Sonia and Kari had rented—on the El Quijote and Bolivia passage—much better than they’d found it. A house with ancient damp in the closets, for example.

While we were talking about nothing in particular with Sonia and César, I caught a glimpse of the photo of Karina that Sonia had as her phone’s wallpaper. She looked beautiful and younger. I immediately recognized the blouse she was wearing, because she had it on the night Jonah and I met her—on a terrace in Buenos Aires. I still remember her distinctive look, the one we first crossed paths with: the shirt buttoned all the way to the neck and lips painted bright red. Her bangs skimming the edge of perfectly lined eyes, her jaw slightly forward, crowning her features. The eminently folk Karina—the one I heard sing “No le digas qué hacer” so many times.

Six months earlier she had arrived from England and was weighing options for her life back in Argentina from the “casa del viento,” in her native Balcarce. That’s what she called her family’s chalet between fields and the low mountains of Buenos Aires Province. I can vouch for it: the wind there could wrap you in a whistle, taking over doors and windows. Kari would later use that phrase as the title of her first LP, which she recorded twice. The first time, with the equipment James—her partner at the time—had brought from England. But those recordings were discarded in the middle of a crisis that, among other things, led to their breakup and pushed her to start the record over from scratch.

The second attempt found her in Buenos Aires, in a creative partnership with Andi Barlesi (Los Álamos, Springlizard, Kulku), who worked with her through the production of the album. What stands out is the acoustic sound of Karina’s precise guitar, a few subtle banjo and double-bass arrangements, and the high register of her voice—sweet and devastatingly melancholic—right up front. A touch of delay. Lyrics in English and lyrics in Spanish that I learned by hearing them live again and again: “Cuando no te pasa a vos, no es verdad. Qué fácil es hablar. Qué fácil, criticar.”

Four

I think Karina returned to Buenos Aires with the tacit recommendation of the Hermanos MacKenzie —Ceci and Galgo Czornogas— who had stayed at her place while touring in England. Jonah and I first ran into her when we went to hear Marina Fages and Lucy Patané in an apartment one of them was minding in San Telmo. It was the era when they played together constantly, and they’d organized a small acoustic show to raise money for a European tour. Couldn’t get more 2010s than that.

Loose images from that night still float up at random: Marina carefully writing the homemade menu on a chalkboard —the food they’d cooked to offer, too. Memory has its own reverberations. But Marina’s fine motor focus, acoustic instruments, and lentil burgers also pull me back to a Buenos Aires terrace night: under a soundtrack composed by two other friends, a friendship with Karina began for Jonah and me —one that marked us with the indelible stroke of a life made in common, a life you play and risk, a life you let others affect.

Not long after that meeting, we were already in Balcarce. We were invited. We invited ourselves. Karina and her family picked us up in Mar del Plata after a Los Palos Borrachos gig —summery, drunken, chaotic, like all of theirs.

Sonia made sorrentinos for lunch the next day. At siesta time, Jonah recorded banjo and clarinet arrangements for the first version of the album Karina was preparing —arrangements that would never be used. César kept popping in with some excuse, to tell Jonah about his own musical influences and his childhood memories from the United States. He’d play a few chords on his guitar, step out so as not to bother us, then come back in with even more enthusiasm than before. You could tell he was happy to have company in the house. I think I was there to register those backstage moments and keep them forever.

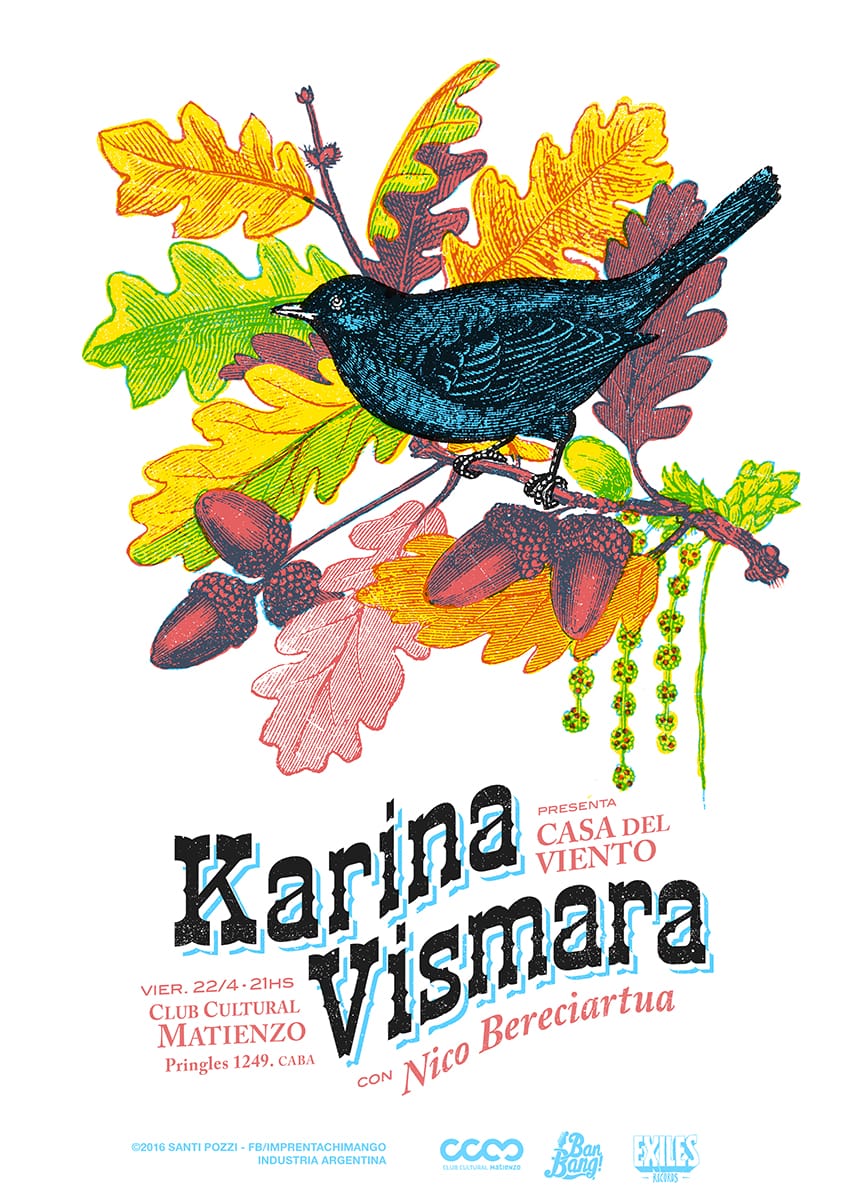

A few months after that visit, Karina left Balcarce again and settled in Buenos Aires. Later she presented Casa del viento at Centro Cultural Matienzo, in its newly opened location in Almagro. Nico Bereciartua opened that night; Santi Pozzi designed a beautiful poster that comes in handy now as a memory aid.

With a kind of ad hoc super-band, Kari closed the night with her version of Neil Young’s “Old Man”. Maybe that cover was a prelude to the more powerful sound that would come later with Selva (2019), her second record, when she gathered an incredible lineup to bring her compositions to life with electric guitar, bass, and drums.

In Buenos Aires, and as time went by, Kari made new friends —more and more. She became a regular at spaces like Open Folk Buenos Aires and Sofar Sounds. She toured Europe. Then Mexico, I think with Lola Cobach. Still, I never quite knew whether touring treated her well or not. To me, she came back tired. A little worn down.

Through all the comings and goings, her long-standing ties remained: Micha —whom we’d always run into up front, going hard at her shows— and Toti, her photographer friend who shot her for the cover of her last record. Her older sister, Pamela. There were loves and heartbreaks too. I reserve the right to sidestep them, carefully, in this recounting.

Five

From that September goodbye, I also noted in my diary:

With Sonia and César we also talked about Kari’s grandfather —César Senior— who worked at INTA’s Experimental Station in Balcarce. In the early 1960s he lived with his family for a few seasons in Ithaca, in the United States. He’d traveled to pursue a master’s in rural philosophy and psychology —at none other than Cornell University— as part of the training programs INTA promoted among its staff back then. Then they returned to Balcarce to apply what he’d learned. Maybe something in Karina’s own path reaches back to that story: train abroad, then return home and put it into practice.

César —Junior— told us about the magnificent camping kit his father bought while they were living in Ithaca, a kit he still keeps in the attic. It even includes a portable bathroom with pipes and everything. What mementos of his daughter will César keep in that attic now? I keep one in the bathroom closet.

When Rosita, our first daughter with Jonah, was born in 2016, Kari came to meet her at our place. She showed up with a bundle of baby gifts that included a hooded towel. With that cloth I wrapped our baby in a warm hug after every bath, until she grew so much the towel became too small. Years later, I used it again to dry Aurora, our second daughter. Rosa remembers Karina. Aurora doesn’t.

I can’t connect to these stories these days without feeling the push of what we once were slipping through our hands like sand. Even if it sounds embarrassingly baroque.

Fittingly, Sand is the name of Jonah’s EP that includes songs he sang with Kari and with Julia —aka Betty Confetti / Betty Blight. They recorded the vocals in the home studio before the pandemic, back when Julia was the only one with a serious illness —recovering from a fairly complex heart condition. Back then the three of them would rehearse in the sun, in our backyard. Rosita and I were a privileged audience to those delayed three-part harmonies, while one of the girls pumped a shruti box.

They were exploring a shanty sea song, “Blood Red Roses” which Jonah and I used to listen to on Memories, the second album by Mimi Baez and Richard Fariña. And the way Sand hits me now, that record feels like it’s playing against a death: Fariña’s —killed in a motorcycle crash before the album came out— and Karina’s. That cover has always split me open, with the portrait of Mimi Baez, widowed at 21. Fuck, it’s brutal when young people die.

Six

Maybe turning 30 in a city that, I always felt, asked a lot of her and gave her little toughened her up. And maybe I can hear some of that in Selva, her second LP—one that blurred for me between the pandemic, my postpartum stretches (seasons spent at home), and her cancer diagnosis, which required her to stop playing live to focus on her health. The highs are a bit sharper, less wistful.

If Casa del viento was mixed by Noah Georgeson (of Vetiver), Selva was recorded and mixed at the legendary Estudios Ion by Pájaro Rainoldi —my personal hero from the old-school skatepunk guard.

Seven

Karina’s death found us dogsitting her dog, facing the question of how to tell an animal, somehow. We held him in our arms, wordless —just a hand moving up and down his back. But really, I think her death found us facing the question of how to tell ourselves, and having to accept that sometimes life hurts, and things do not happen the way we want them to.

In that same diary entry, I wrote, finally:

I still can’t process it —I can’t believe Kari died. It feels more like she went on a trip to a place she won’t come back from. But there’s a kind of enormous familiarity that keeps me from thinking she’s gone.

This January seems determined to remind us that that familiarity still moves among us. Because what are the odds that, in the very days I’m writing this —while Jonah and I wade into the cold water of Golfo Nuevo— and when we duck into a little café to buy something sweet for mate outdoors, Karina’s songs are playing?

A caress runs up and down a spine.

Friend: we’re listening.