In English, the saying goes: old habits die hard. That neat little phrase would be perfect if I wanted to sum up, in a very simple way, what happens to me when I read printed magazines. An old habit. A weed that never dies. A hard habit to break in the life of a forty-something woman clinging to physical formats.

But among cultural historians there is a more thorough hypothesis circulating, one I feel more at home with. It proposes that periodical publications are a format with a different kind of pace, marked by a particular distance from day-to-day events.

In his book on Latin American cultural magazines, Horacio Tarcus argues that in Latin America –a true continent of magazines– these publications are born and come into their own once the emergencies of the daily battles during the wars of independence and the civil wars have subsided. As the press system grew more complex throughout the 19th century, the magazine carved out a place as a more distanced and therefore more reflective form than daily political journalism, a form in tune with the slower tempo of intellectual work.

Hence many readers also recognize in this format something more than a mere receptacle for "content", and see the magazine as a collective actor with a key role in weaving cultural narratives. Magazines test, elaborate, synthesize, distill, dispute and stir up ideas and approaches, the various currents of a given historical moment, all at the cadence proper to intellectual work. I think this is why I read them. Or at least this is what I read in magazines.

So is it too much to lean on these hypotheses, developed within academia, in order to understand and celebrate the nine years of a periodical publication about video games?

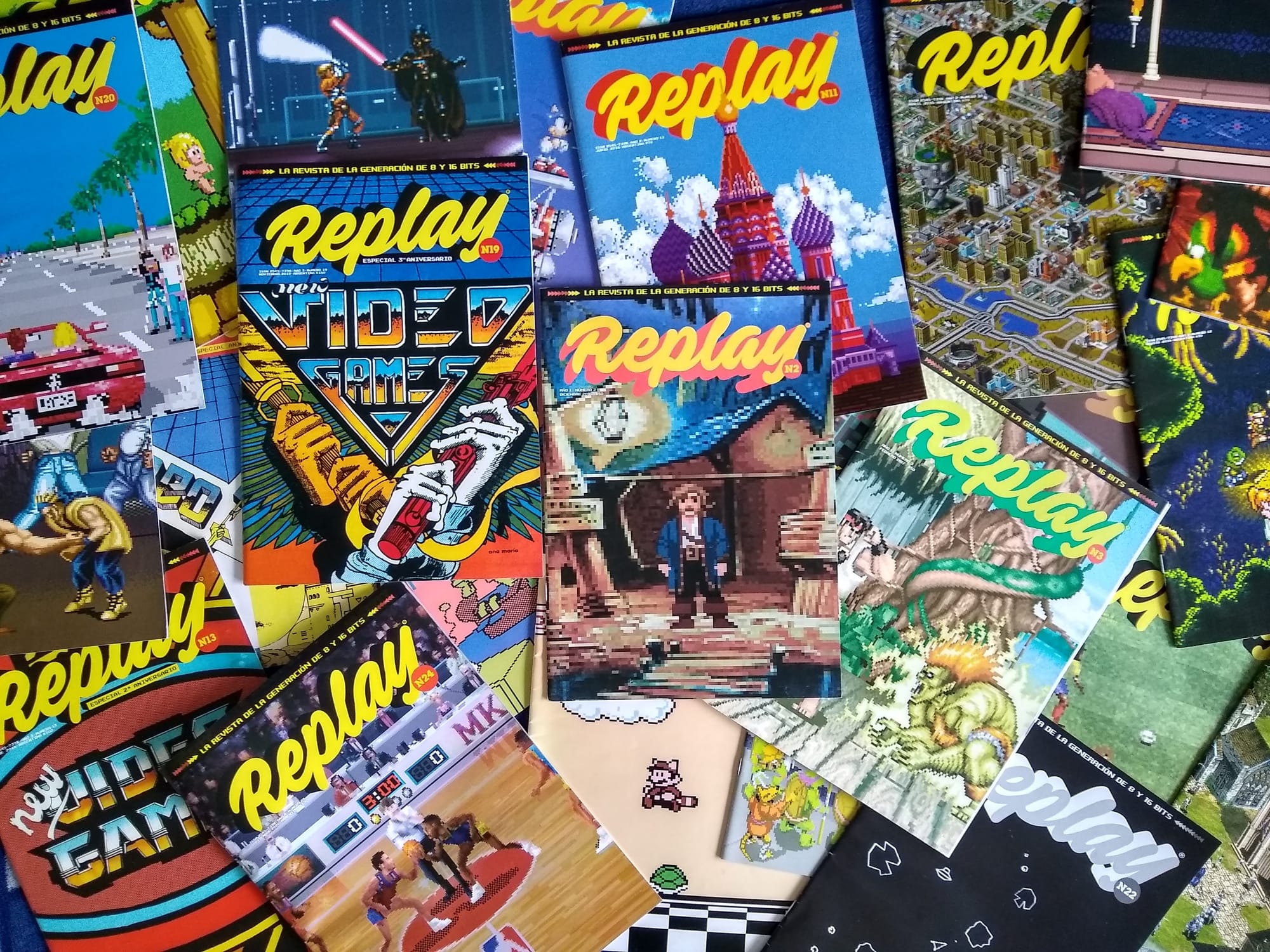

In October, Replay –a self-managed magazine and editorial project, meaning an initiative without backing from major private or public investors, advertisers or established publishing houses– marked nine years of existence and print circulation. It's a truly remarkable span when you consider how hard it is to manage, let alone self-manage, any kind of venture.

In the case of this periodical publication, those nine years can also be broken down into the following notable figures:

- 55 issues published

- 2 issues re-edited (revised and expanded)

- 1,744 printed pages

- 730 articles produced

- 75 authors published

- 500 copies per print run

- 490 loyal subscribers

And a narrative arc of its own, which begins with a gesture of retro identity-building but culminates in historical research, within a disciplinary field that is practically unexplored in Argentina: game studies and, more precisely, the history of the local video game scene.

Let me take it step by step, starting at the beginning of this beautiful story of people learning to do things together.

Issue Zero

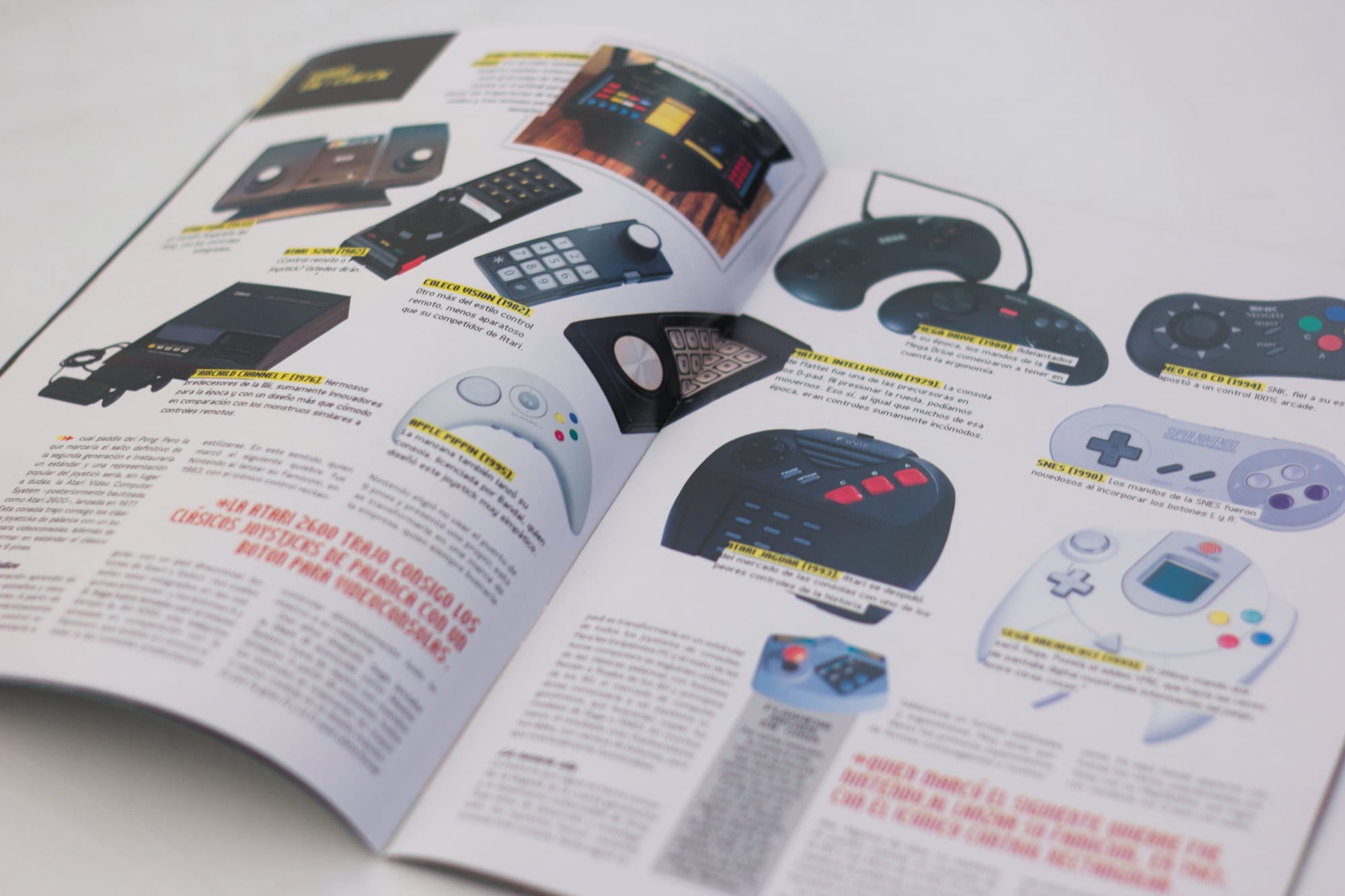

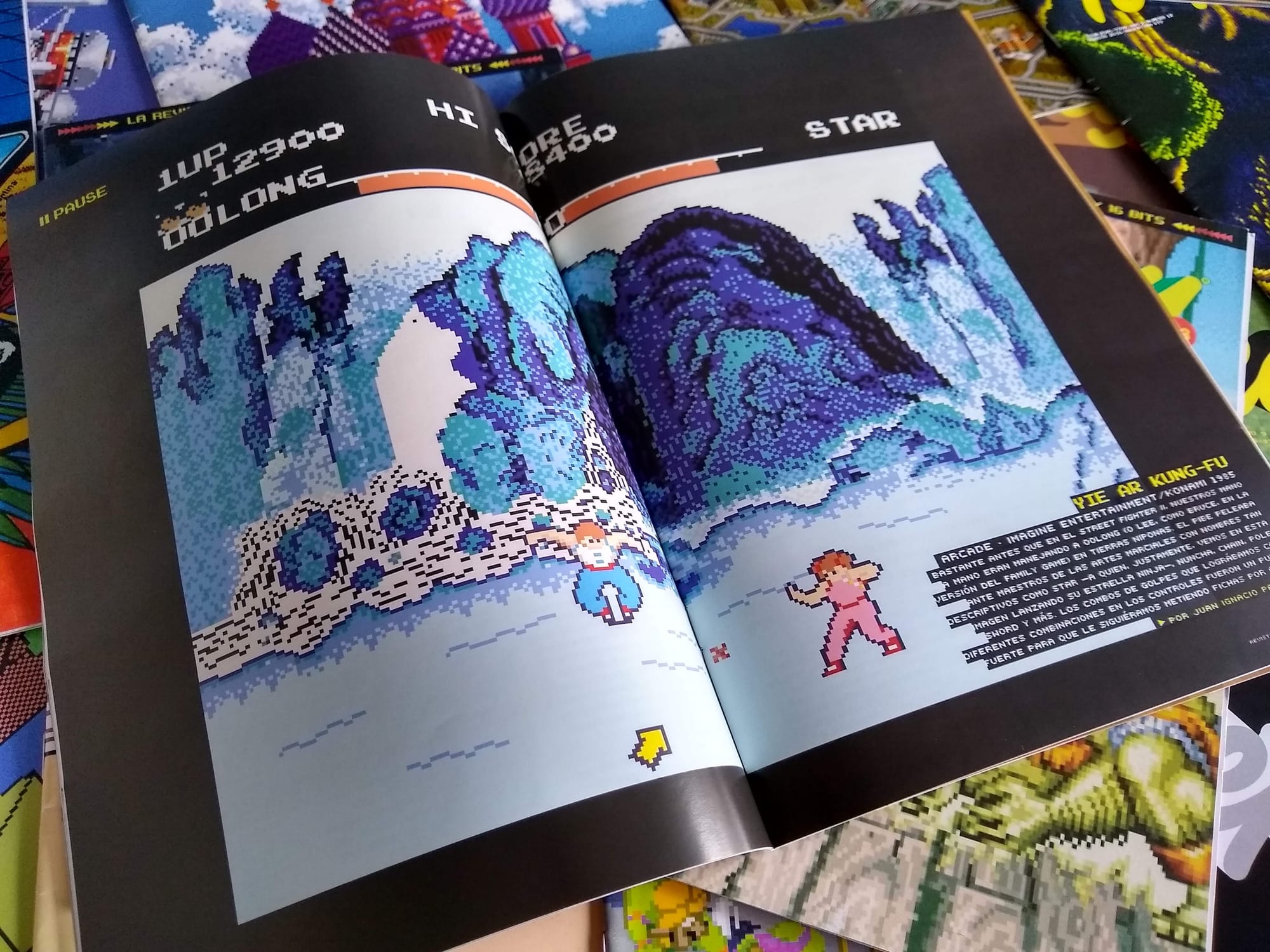

In 2016, graphic designer Juani Papaleo wanted to create a periodical publication in the style of the British magazine Retro Gamer: a video game magazine with a nostalgic imprint, appealing to the identity of a generation that grew up between the 8-bit and 16-bit eras. He also wanted something neat and professional. He had sketched out some article templates, but he needed people to write them.

So he put together a sort of issue zero and did something he had never done before: he went to a video game event, hoping to find people who would connect with his idea and want to write. "I went with a copy of Retro Gamer tucked under my arm, as bait", Juani tells me. "I was hoping someone would tell me they knew the magazine. And then I planned to show them a few mock covers I'd made as issue zero of Replay and invite them to join."

At one stand he ran into Daniela, who suggested he get in touch with Carlos Maidana (better known to everyone as Kabuto), who would surely be interested in his magazine project. With that little piece of information, Juani went to Kabuto's shop in Flores and told him about the idea. Kabuto promised to find writers and set up a bit of scouting. From the endless threads of ForoFyL –the legendary forum of the Philosophy and Literature Faculty at Universidad de Buenos Aires– came Eze Vila. And through Twitter came Sergio Rondán. "I knew Kabuto from the forum, because he had posted a lot about video games", Eze says. Sergio adds: "I was following him on Twitter and saw that he was talking about a magazine. And since I’ve always liked writing but had never had the chance to publish, I replied to a post and joined in".

Then Juani launched a campaign on Idea.me to finance the release of the first issue. And with a final financial push from his brother –his partner in childhood adventures and long summer afternoons spent in arcades– the first issue of Replay finally saw the light of day.

Anniversaries and Turning Points

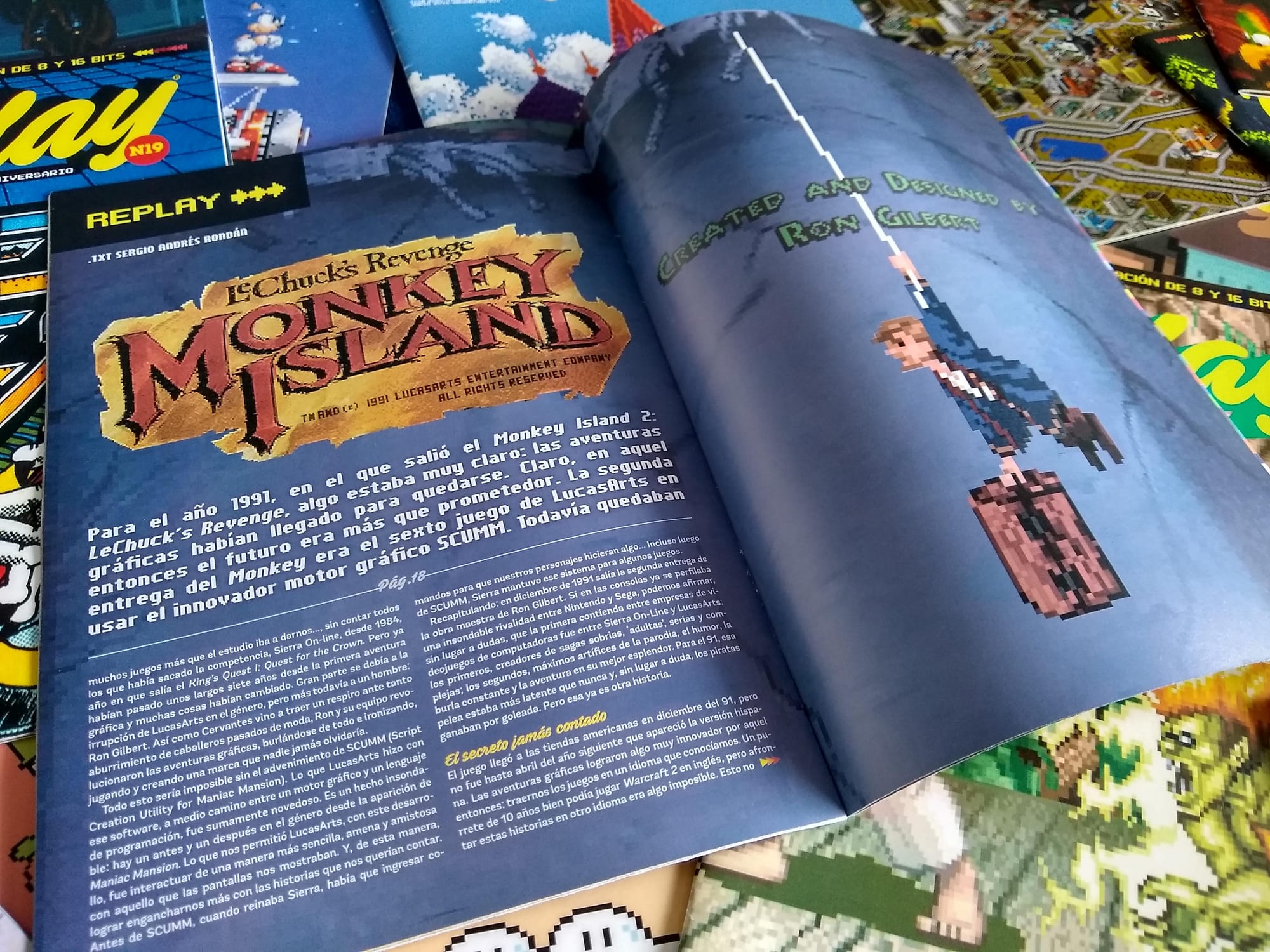

By the second issue, the first crucial incident had already taken place, one that, according to Eze, would help reorient the magazine's destiny. "Because of a string of coincidences", he recalls, "for issue 2 we interviewed Ron Gilbert. Thanks to a contact I managed to get into his press conference, and we ended up interviewing him in a bookstore in Palermo. Until that piece, none of us had really planned on interviewing major video game legends. But that feature happened. Emboldened by the experience, for issue 5 Sergio and I interviewed John Romero –the creator of Doom– over a video call. And those two interviews gave us a huge boost to go out and produce more material." Sergio adds: "We realized we were in a position to interview these people. And that if they had taken us seriously, we could keep trying and reaching out to others".

In this sequence of discoveries inside the editorial lab, the magazine's first anniversary brought another spark. "At that point we thought it would be interesting to start digging into certain local developments", Sergio tells me. "By then we already knew a bit about the history of the Trucotrón, for example, and of a few other arcade cabinets that had been made here in Argentina. It was part of a kind of popular lore among the people and communities who had spent time in game arcades. But no one had investigated it in a very systematic way."

With a third issue on the horizon, and a friendship between Eze and Sergio forged in the heat of complaints, suggested edits and the beginnings of a shared production routine, the pair got excited and went out to track down testimonies about national developments on which there was little or no information.

"Nostalgic obsession?" Eze answers my implied question: "For the first anniversary we put together an issue devoted one hundred percent to the Argentine scene. And with that we also realized that, for us, it was much more interesting to make a magazine that focused on, or at least leaned toward, research. Not out of nostalgia, but out of a shift toward history. That's how Replay became distinctive as a magazine that, if not strictly archival, is at least a place where histories can be pieced back together and where research can be done. And I also think that our pieces on foreign games, which had nothing to do with the national scene, began to soak up that same impulse to recover and narrate the history of video games, with a special emphasis on what the Argentine scene was like".

Because, as they write in their wonderful interview with marquee painter Ana María Malagamba, "the national history of video games is full of unknown but extremely influential characters". Eze explains: "In the second year of the mag there's a run of interviews with these protagonists: people like Juan Kurhelec –founder and owner of the Playland arcades– or Ana María Malagamba herself. They were very well known in the world of collectors, among people in the scene, but almost nothing was known about them in print. No one had really sat down to talk with them, there were no published interviews".

Sergio adds: "Many of these people were simply there. All you had to do was ask them". Eze: "There were also people who weren't used to giving interviews. Like Ana María, who didn't really understand why anyone would be interested in her work. But then we clicked right away. Anyway, between the second and third year, realizing what could be done in the magazine –with a different level of seriousness– began to bear fruit. We felt more confident, and that made us more reliable for certain interviewees. And we also opened up the panorama. From video games and local developments we moved on to computers. And that's not even counting the material we can include now. For example, in issue 50, which we published this year, Sergio goes after the history of ARPAC and the first Argentine cyberspace".

However, the work has its complexities. "Sergio and I have the feeling that this is an oral history that, in five or ten years, might simply disappear", Eze tells me. "All these people who carried out those early developments are already quite old, and this is the last chance to record their work. Some have already passed away and we didn't arrive in time. On top of that, searching for data in archives is very difficult, and people remember things as best they can, so conflicting versions emerge. It's very hard to cross-check. So we prefer to publish what we have and, if necessary, let people come back later and correct us. A lot of people get in touch after an article is out. With the magazine, it's always about casting the net and seeing what the piece brings back. Lighting a beacon and saying: here we are."

I return to the idea of the magazine's slow tempo as a laboratory space and a site of intellectual reflection, as a collective actor that proposes a way of understanding –or, in this case, of reconstructing– a local cultural history. And I think that, after this story as told by Juani, Eze and Sergio, Replay has fully earned the right to be read and studied with the interpretive tools of academia. In the end, the publication identified a gap, an under-researched area in the history of video games in the country: their technological development, their cultural impact, their expansion as a form of entertainment. Today the magazine takes all of that as a starting point, an excuse to strengthen community.

Present Continuous

After nine years, Replay continues to grow on paper, slowly but surely. The magazine started with 28 pages per issue. A while ago it reached 32. For anniversaries it allows itself the luxury of adding one extra signature and hitting 48. And the latest issue was, quite simply, an extraordinary feat: 64 full-color pages of original reporting and research.

Is the magic still intact? Eze replies: "The day the magazine arrives from the printer is still overwhelming for me. I still get excited when I see the delivery van pull up, the driver hauling boxes of magazines out of the Kangoo. And I really enjoy preparing the shipments, going to the stationery store to buy 36 rolls of adhesive tape. But we've also questioned many times how we can keep going. And the point we always agree on is this: if we can't make it on paper, we won't make it at all. Because paper gives us a way of doing journalism, doing research and working that we're very happy with. Its limitations also end up helping us offer more refined material."

A new wave of researchers has also joined the project, like Emmanuel Firmapaz. Eze tells me: "Emma felt the call. He already knew the magazine, saw what we were doing and reached out to us. At the time I was a bit lost in life, working on the documentary Fichines, and I really felt Emma's call. He basically said: 'This is very important, I'm going to give what I can to the magazine'. And then he founded Club 404. The great thing is that when it started to feel like a slog for us, he appeared, and now he's the one carrying the torch."

Happy birthday, Replay. And, paraphrasing one of Eze's editorials: thank you for the hours of freedom granted in the form of reading and discovery, all circling around the history of our very own national jueguitos.