RoboCop is one of the masterpieces of Dutch director Paul Verhoeven, who managed to pull off a kind of magical alchemy between industrial cinema, science fiction, and a razor-sharp satire of his time. A triad made up of RoboCop, Total Recall (based on a story by Philip K. Dick), and Starship Troopers. Three films that will inevitably enter our canon and which we’ll keep revisiting as circumstances allow.

Verhoeven mocks his own era by weaving contemporary elements into his films, pushing them toward satire and thus laying bare the mechanisms of the desiring-machine –but only for those who approach them with an attentive eye. Just look at the role played by the fictional TV shows and advertisements. For everyone else, they might function as mere set decoration, but not as little capsules that conceal the author's vision of the thing being satirized.

So much so that, in our current world of cyber-culture, some fragments of the brilliant Starship Troopers are no longer used as elements of anti-war satire but, on the contrary, as justifications for warlike violence. And not only that, but those who point out the contradiction are mocked through a whole economy of memes. This can open up another debate around the author's intentions and how the work is received; especially a kind of revisionism of the film canon where Fight Club, American Psycho or Star Wars are re-read in a reactionary key, with Tyler Durden or Darth Vader recast as the real heroes of their respective sagas.

Those who defend this reactionary reinterpretation –the ones running the operation, not just those who follow along– make fun of anyone who sticks to the supposed intentions of the author, and defend their heterodox reading not as a misreading but as a political rereading of the whole thing. In that sense, justifying the actions of the human army in Starship Troopers is ultimately a political justification of the Western war machine against an "external" enemy who, in our era, takes the form of the Arab or Muslim immigrant.

But you don't need to dive so deep into the hermeneutical disputes of pop-culture nerds to understand the complex double nature of a critique of its own time, made from within the very apparatuses of power –like a Hollywood production that ends up captured by the logic of its own success.

That is precisely what happened with RoboCop, if memory serves. Both the film and I were born in 1987. I vividly remember that, during my childhood, RoboCop was just another franchise, like G.I. Joe, Rambo, Terminator or Ghostbusters. Meaning: besides the films, it had its own animated series, its video games, and a line of toys. A type of prefabricated, corporate culture that is itself the object of satire inside the original film.

Even though the unexpected success of the first installment led to two more films and the inevitable bastardization of the original concept, that first movie remains a cinematic monument to what we might call "sci-fi". Which, as Isaac Asimov says, is a kind of sweetened, commercially acceptable version of hard science fiction. Star Wars is sci-fi; The Martian Chronicles is science fiction.

RoboCop tells the story of Officer Murphy, a cop in the troubled city of Detroit whose personality and skills fit the archetype of the Paladin. He is a man of the law, a good father, dutiful and obedient, a symbol of everything heterosexual Protestant masculinity is supposed to represent. He is, strictly speaking, a WASP. But he is not just a cop: he's an Agent of Order. In the North American film tradition, that classic figure is embodied by no one less than the Sheriff. The sheriff is not just a police officer, not just a gunslinger with a badge –even if, in the end, that's exactly what he is– but the one who restores peace, order, and therefore progress to towns ravaged by gangs of outlaws.

Which is, precisely, the state of the Detroit Murphy has to patrol: a city blown apart on multiple levels. Economically, socially, and morally bankrupt, with crime through the roof and functioning as an index of general malaise. A dozen cops die in the line of duty every day. To soften the impact of the crisis, the mega-corporation OCP (Omni Consumer Products) takes over the management of the police force. The one who pulls the strings is OCP's vice president: Dick Jones, the number two at the company. He seeks to implement a technocratic solution: the military-grade ED-209 robot to wipe out the criminals. And, as a bonus, use Detroit as a testing ground in order to sell the ED-209 as tried-and-tested "combat-proven" military hardware.

But this pacification plan –an automated shower of bullets– is part of a broader OCP strategy to transform Detroit into a brand-new city: Delta City. The project is so massive, and would create so many jobs, that OCP has enough power to place itself above the rule of law. A kind of techno-oligarchic utopia that mirrors the hegemonic ideology of the moment, embodied in the governments of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

But, as Tusam used to say, it can go wrong. Jones's robot blows away a company executive during a test, and the technocratic plans are temporarily shelved. That's when another ambitious young executive sees his chance to launch the RoboCop program, capitalizing on the failure of his internal rival. The RoboCop project is a less grandiose version of Jones's technocratic maximalism: quicker to roll out, more flexible, and even less bureaucratic within the rigid administrative structure of OCP. Young, hungry blood leveraging the failure of the previous generation's executive bureaucracy, seeking the love and favor of the company president, whom everyone simply calls "the Old Man".

There's a Snake in My Boot

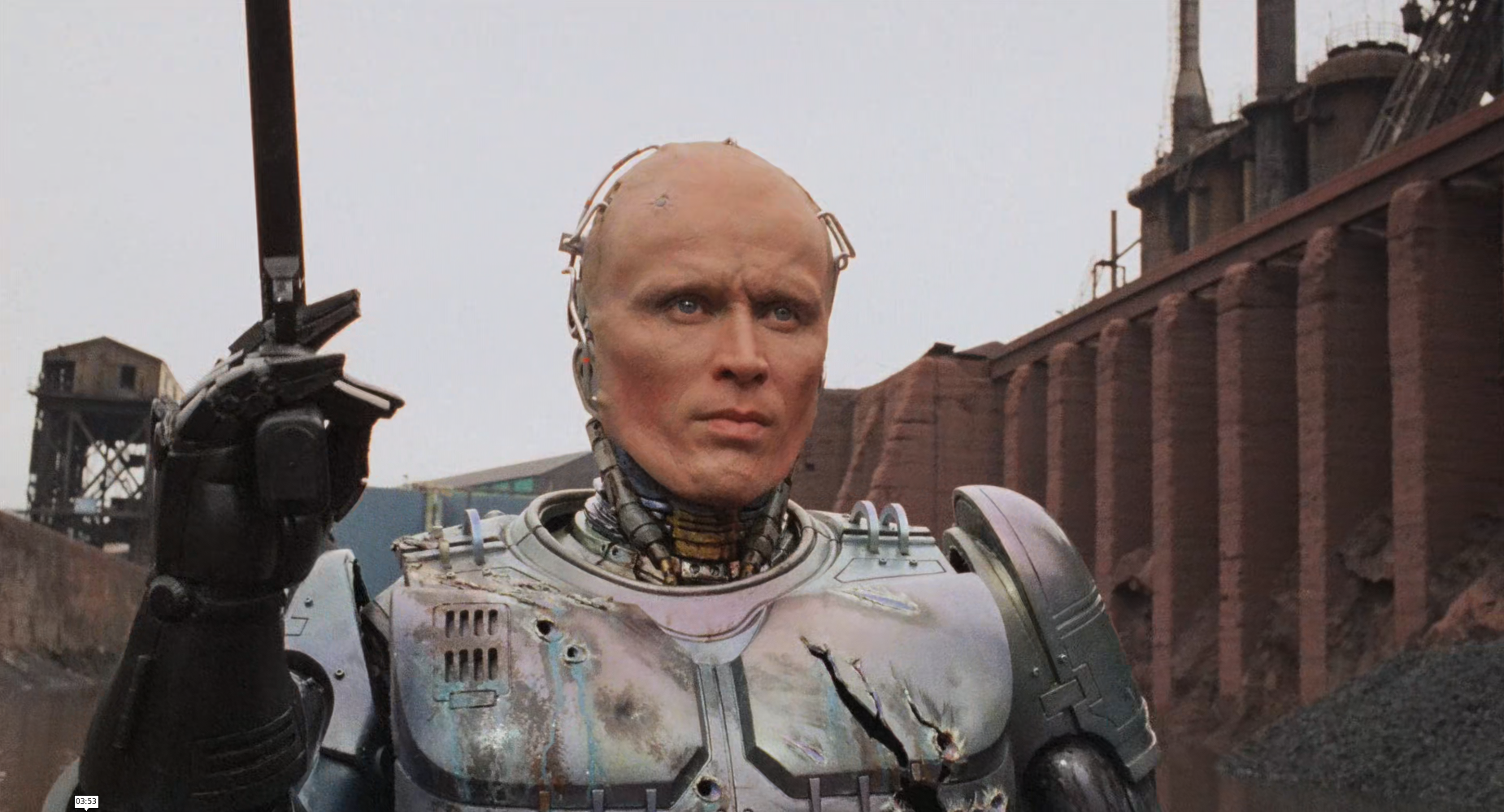

Murphy gets transferred to the most dangerous precinct in Detroit. The station house is a pressure cooker. Cops are dying at a rate of one a day. Everyone is on the verge of breaking and going on strike against OCP. The only thing keeping them in line is the authority of the precinct captain, who shouts: "Cops don't go on strike –we're not plumbers". The district is terrorized by a narco-gang that destroys everything it touches. Sooner than we'd like, poor Murphy falls into an ambush in an abandoned factory (another period marker), where he's riddled with bullets and practically torn apart. The execution scene, complete with mutilation, is impossible to forget. As dead as he is, he's scooped up by that group of young OCP technocrats. And when he wakes up again, he's a cyborg. Once more, Frankenstein's monster –but with computers. As the film's unbeatable tagline says: part man, part machine, all cop.

The rollout is a success. RoboCop goes out on patrol and Lewis, his former partner, recognizes two gestures from the man who fell in the line of duty: the way he twirls the gun around his fingers before holstering it –like a cowboy, except into a holster hidden in his metal leg– and the sparks that fly when he peels out of the police parking lot at full speed. There is still a human core beneath the machine.

RoboCop is programmed to obey four directives: serve the public trust, protect the innocent, uphold the law, and a fourth directive that remains classified for plot reasons –but is, in essence, the kernel of the film's ethical conflict: any attempt to arrest a high-ranking OCP executive triggers an automatic shutdown. That's how OCP guarantees total control over its product and places itself above the law.

Everything that comes after is pure plot mechanics: RoboCop showing off his near-perfect ability to detect crime, analyze data, fight criminals, and put them under arrest. But something isn't quite right. RoboCop is haunted by nightmares fed by the memories of his own death and by idyllic flashes of his human past: his wife and child. Using every tool at his disposal, he tries to unravel the plot behind his murder. Which, in the end, is fairly simple. Dick Jones is partners with Clarence Boddicker, the crime boss who had him executed. Jones, in turn, plays both sides in the classic move of selling the problem in order to sell the solution. Without any scruples or moral limits, Boddicker takes care of OCP's internal competition, funds his gang through drug trafficking, and gets military-grade weapons directly from Jones to take out RoboCop, who's closing in on him.

The dramatic tension peaks when Murphy, battered but fully aware of who his enemies are, wipes out the drug gang at the abandoned steel mill and exposes Jones's plans to the Old Man at OCP –who fires him on the spot, allowing RoboCop to fill him with lead. And so, at least for the time being, Sheriff Murphy restores order to dear old Detroit.

Law, Vengeance, and Memory

Beyond Sheriff Murphy's quest to restore order, RoboCop lends itself to at least a couple of further readings. First, there's Verhoeven's mastery at crafting action cinema rooted in the violence of the body. Anyone who watches the film again today will be confronted with a festival of mutilations, gunshots, and exploding bodies that are impossible to erase from memory. The near-final scene where one of the criminals is doused in toxic acid until he melts, only to be run over by a patrol car and splatter his "human juices" all over the windshield, is a little masterpiece in itself. And it even left us this meme. The tone of RoboCop is inescapably crossed by explicit violence.

Second, there's the constant tension between vengeance and justice. As RoboCop reconstructs his own memory, the human part clashes with the machine part and with the rules governing his interventions. And yet, despite having been murdered by a gang of outlaws, RoboCop consistently acts within the law. He holds on to the notion of being a public servant –and it's within that narrow gap that he can still align himself with some kind of moral compass. He's a different kind of entity than ED-209 because he can make moral judgments without sacrificing effectiveness. As the violence escalates and the collusion between OCP and Boddicker's gang becomes obvious, RoboCop also steps up his firepower. By the end, he's no longer trying to bring his enemies before a jury –he simply annihilates them. Inevitably, a good cowboy has to solve problems with bullets. That's why Colt's most famous revolver is called the "Peacemaker".

Third, there's the plot of the omnipresent corporation trying to take over every last corner of the city's life. Dick Jones is, in some sense, a foreshadowing of what Dick Cheney would become years later: a number-two in power with more power than the president himself, able to weaponize and instrumentalize the most marginal elements of society in order to roll out technocratic "solutions" backed by long-term, billion-dollar military contracts. If we really think back to the whole Iran-Contra affair, as mentioned earlier: the United States illegally sold arms to Iran and, with that money plus various maneuvers linked to drug trafficking, financed the "Contras", paramilitary groups in Nicaragua fighting the socialist Sandinista government. All the key tropes of the case –illegal funding of armed groups, arms sales, and drug trafficking– are part of the corroded landscape of post-industrial Detroit, where RoboCop has to act as guarantor of order.

And fourth, it's worth highlighting the use of television within the diegesis of the film as a form of meta-commentary by the author on the world he's created. For starters, explanations about Delta City's crime wave are delivered through newscasts that cut to all kinds of OCP advertisements: the company that owns both the channels and the products being sold. At the same time, almost every character in the film watches the same lowbrow comedy show, somewhere between Olmedo and Rompeportones: a dirty old man surrounded by vedette-style women. Everyone laughs. Cops, crooks, civilians. OCP works as a metaphor for both the military-industrial complex and the industrialized hetero-culture driven by audiovisual entertainment. A current in which RoboCop itself would be inserted –but in the real world. Oh, the irony.

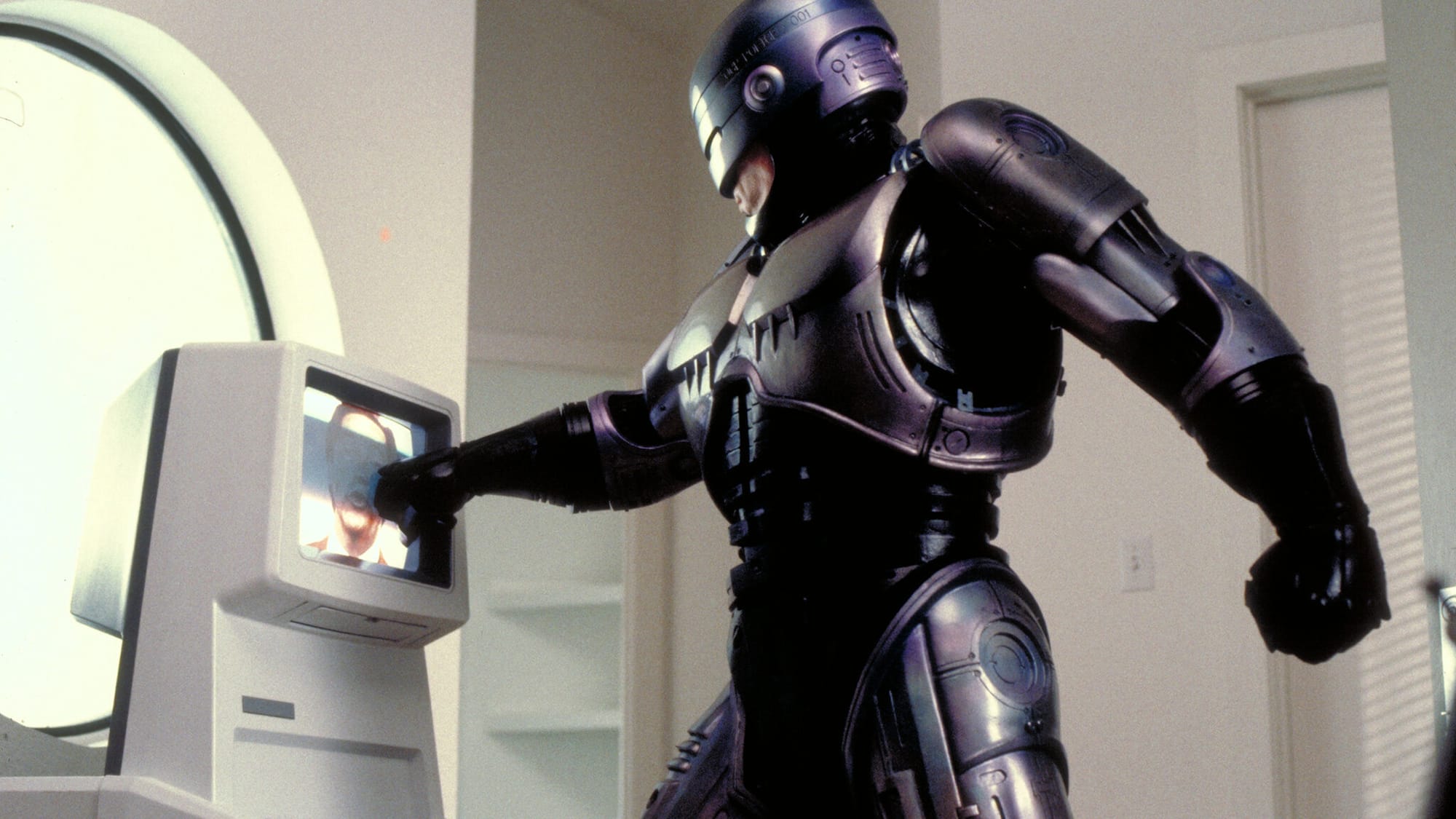

All the screens –and RoboCop's own video recordings via his cyborg vision– play a significant role. When Murphy returns to his house, he finds it empty and up for sale. A totem-like kiosk with a TV screen plays an automated sales pitch, somewhere between today's security totems and a Remax real-estate agent. The scenes in the house have a peculiar dream-like aura, because RoboCop's memories seem to merge with his own video recordings. In this way, video takes on that double role of fabricated memory and vivid recollection, blending reality, memory, and desire. The memory sequences become a bit liminal: memories processed in PAL/NTSC that prefigure the whole retrowave aesthetic that flooded YouTube in the late-pandemic era.

Finally, Murphy not only manages to fully accomplish his mission of restoring order to the godforsaken city of Detroit, he also succeeds in synthesizing the two natures that now make him up: the machine (and OCP's product) and the remainder of humanity that once defined him. In the last frame of the film, RoboCop answers the question "What's your name?" with a single word: "Murphy", making that synthesis explicit. On the one hand, his human nature, his paladin morality, and his love for his family. On the other, the machine that dispenses justice with surgical precision. It's at this point that the cyborg fully appears as something fundamentally hybrid.

For all these reasons, RoboCop rises, without any room for debate, to its rightful status as a classic –and we are proud to welcome it into the Canon.