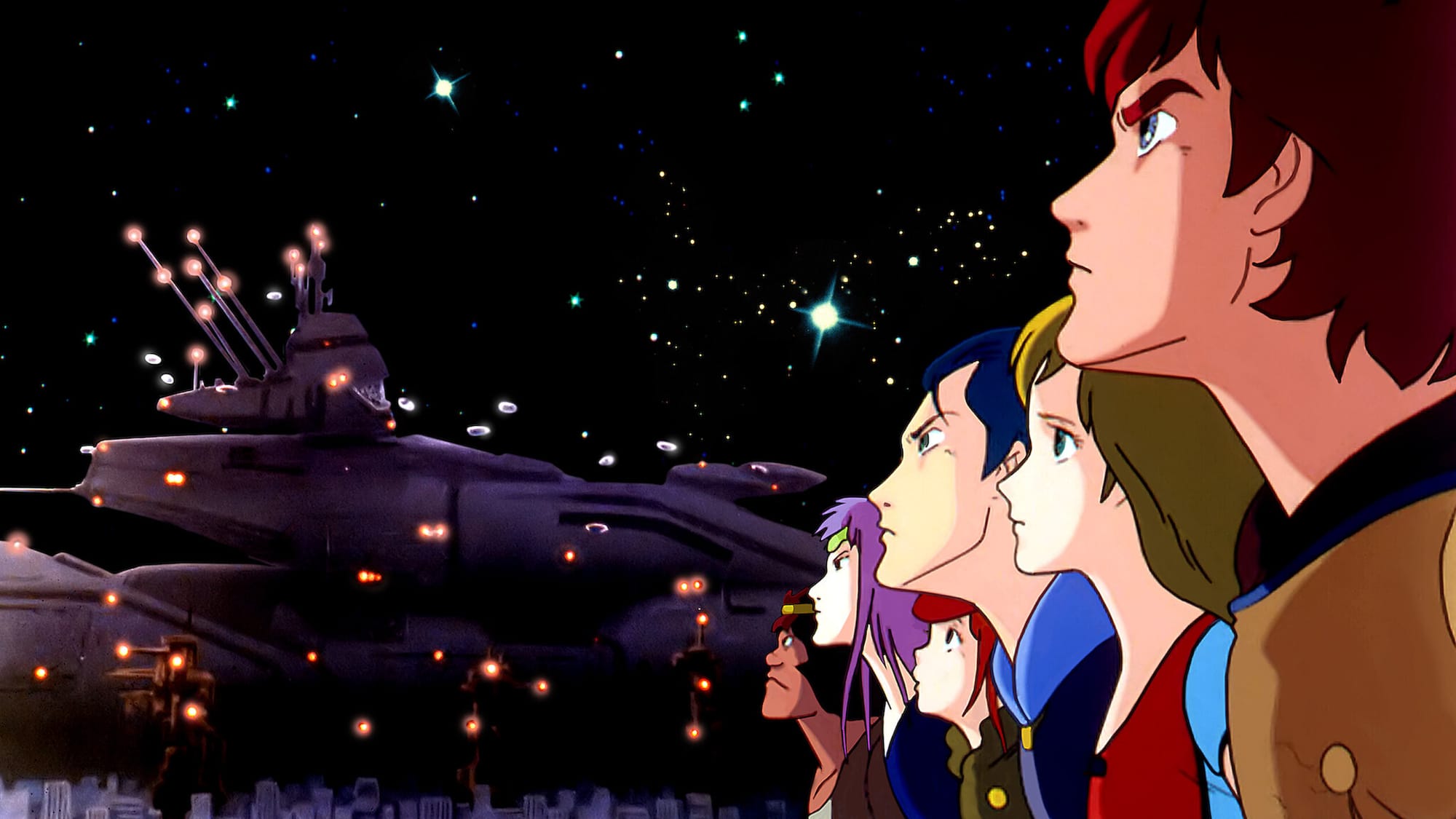

Childhood in late-1980s Chile. Playing in the street with the neighborhood kids on a normal afternoon, until suddenly the game stopped because someone remembered: "Robotech is about to start". The most incredible series my generation got to enjoy. It drew us in with its mecha and spaceships, but at the same time it showed us that in life we can lose, that there are costs to pay, that adventures hurt. It also showed us the kind of heroism we dreamed of having if we ever faced a similar situation. Robotech (1985) made us feel like we were being taken seriously.

However, it wasn't the only series with that narrative intention. There was another one that, at least in Chile, was broadcast by UCV Televisión, a channel from Valparaíso that reached only Santiago and the surrounding areas: Conan, el niño del futuro (Future Boy Conan), from 1978, aired in Latin America toward the end of the '80s. It was less widespread, but in many ways comparable to Robotech. Both are futuristic science-fiction series that anticipate apocalypses; both have a continuous, serialized plot; and in both, human culture is what saves the species.

What many people don't know is that Robotech is a kind of Frankenstein stitched together from three unrelated series. Macross, Southern Cross and Mospeada were the foundations for each "generation" and/or season of the story. The American company Harmony Gold –or rather Carl Macek and his team– provided the narrative backbone that fused these separate series into a single storyline: the struggle over Protoculture. Protoculture is food for the Invid in the third generation, fuel for the Zentraedi in the first, and the engine of the society of the Robotech Masters and their triumvirate of clones.

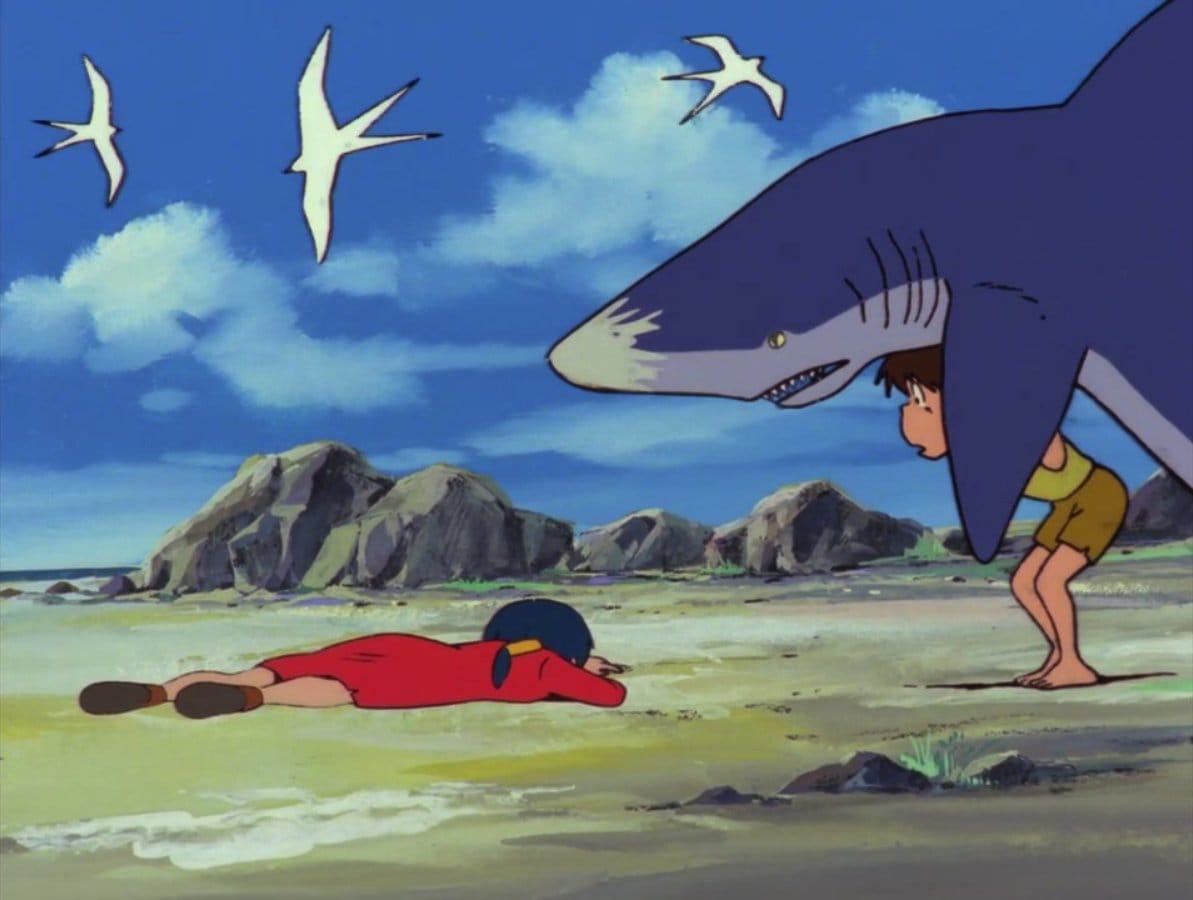

Future Boy Conan, for its part, consists of a single season of 26 episodes. It is a loose adaptation of a novel by Alexander Key called The Incredible Tide. Under its original title Mirai Shōnen Conan, this work was Hayao Miyazaki's first job as a director. The series also counted on the participation of none other than Isao Takahata (Heidi, Girl of the Alps; Marco; Grave of the Fireflies) and Yoshiyuki Tomino (creator of the Gundam series).

Robotech, Global Civil War and the Apocalypse

This is what matters to me now. As a child, standing at the gates of the year 2000 –the foretold end of the world– the idea of surviving the imminent apocalypse felt like something one should be prepared for. And Conan somehow served as a manual on how to rebuild society after a Third World War. The apocalypse in Robotech is different, but it points in the same direction: how do you build a society once the current one has disappeared?

In the case of Macross, the first generation, the trigger is the crash of an alien ship on a small Japanese island. Inside that ship –created by Zor, a scientist serving the Robotech Masters– lie the secrets of Protoculture. It is also the last remaining source in the universe of the Flower of Life, since the planet where it grew was destroyed by the Zentraedi in the middle of a coup against the Masters. Before dying, Zor programs the ship to crash into the only planet where that flower can thrive so that, from its spores, the all-important Protoculture can continue to be produced. That planet is –of course– Earth.

After a global civil war that lasted ten years, humanity signs a peace agreement and does what it usually does after a good, worldwide shootout: it creates an international organization meant to safeguard the peace so that what just happened will never happen again. Ring any bells? United Earth is the name of this organization, an equivalent –within the show's universe– to the Treaties of Westphalia in 1648, the League of Nations in 1919, or our much-maligned UN of 1945, each created in the wake of a unique, world-spanning bloodbath.

The ship is christened Super Dimensional Fortress 1 (SDF-1), but humanity has no idea what it will come to mean for its future. Those of us who watched the show on TV were never told this part of the story, because it happens before the series begins –it is the prequel that was never produced.

I remember wanting to grow up and reach my teenage years so I could have my own plane, like Rick Hunter, flying across the skies relying on my skills and the open air. I identified with him and with his kind of older brother, Roy Focker, who pushes him to take the leap and become a fighter pilot. This worked as a metaphor for the path toward adulthood and taking on responsibilities that lay beyond the aerobatics of the air circus he used to perform in. Roy teaches him that piloting shifts from a game into something very serious. Don't abandon what you love, the episode seems to say –just take it seriously. That, at least, was a lesson I did understand.

Popular Mech-anics for Kids

Robotech also gave me one of the happiest moments of my childhood. As a family, we were very poor and could only afford a small black-and-white television with a red plastic casing and a dial to change channels. To me, Robotech was a black-and-white series.

Then one morning the TV simply wouldn't turn on anymore –on the very day they were going to air what I still consider the best episode of the entire saga: "The Force of Arms". In that episode, what I mentioned at the beginning is shown in its most intense form: human culture as a weapon for victory.

My brother and I were only thinking about watching the show, at least that day. Democracy had returned to Chile only a few months earlier. It was 1990, and the timid, threadbare reforms to the economic model the new government was attempting had led my old man to join a strike –no longer illegal– that resulted in a small victory for workers: a modest pay raise.

So he went to work early, asked for a few hours off, and came home for lunch. He and my mom left my brother and me alone. We had no idea where they had gone; all we cared about was that they would come back in time for us to go watch episode 27 at a neighbor's house. We were so nervous we couldn't even bring ourselves to play –we just sat there, staring out the window at the street, waiting to see them arrive.

There were only a few minutes left before the episode was due to start when they finally showed up. We immediately noticed they were carrying a box with the word "Panasonic" on it and a picture of a modern TV. The joy was immense. My old man is really into TVs, so he was just as excited as we were.

We plugged it in, adjusted the antenna –and suddenly the TV had all the colors. I asked for the remote control and, for the first time in my life, I selected a channel with a remote. I typed "13" and Robotech was starting right then. I don't think my eyes have ever shone the way they did at that moment: we saw the SDF-1 in color, more vivid than anything else in our reality. I think my parents just watched us, smiling at our childlike joy.

Future Boy Conan and the Self-Destruction of Humanity

Future Boy Conan deals with humanity pushing a technology to the point of self-destruction. Here there are no alien civilizations, and the technology itself isn't toxic: it's nothing more and nothing less than solar energy, used to power magnetic weapons more powerful than nuclear ones. That alone already subverts something fundamental: technology in itself has no morality – humanity does. Mankind doesn't destroy itself with hydrocarbons this time, but with something we currently see as "green". The point isn't that solar energy isn't ecological, but that Conan insists it's not the weapon that matters; it's how you use it.

A major difference with Robotech is that there is a touch of magic. The explanation for the continents sinking is that the planet itself responds against the human wars. The main characters possess minor psychic powers, like Lana's: she can talk to birds and hear her grandfather when he calls her mentally; he, in turn, can send her telepathic messages. Soon after meeting her, Conan discovers that he can hear her with his mind as well. But these powers are not presented as superpowers that set them apart from the others; they're depicted in such an organic and natural way that while watching the show, you barely register that such abilities exist. It's truly a narrative delight.

Chronologically, the story begins when mega-earthquakes and catastrophic tsunamis start happening all over the planet. In an attempt to save themselves, a group of astronauts tries to escape Earth, but strong winds and massive volcanic eruptions damage their ship and send it crashing onto a small island where there seem to be no humans. Days go by and they are left to die –until one morning, when all hope is gone and almost by accident, they discover that in its impact the rocket opened up a spring of fresh water. That's how they start fishing, and there is a beautiful scene where they cry when they see a tiny plant sprout among the rocks.

All of this happens before the main plot of the series actually begins. It's just the preamble that gives us the context we need. From these astronauts, a child is born: Conan. He is raised in community, growing up surrounded by wild nature that helps him develop abilities far beyond those of a typical child his age. That too is a kind of superpower, so to speak, but once again the way it is portrayed is so organic, natural and simple that it gives the whole story extraordinary credibility.

When he's a pre-teen, Conan is living only with one of those survivors, whom he calls Grandpa. The old man knows perfectly well that he doesn't have much time left, so we often see him writing his memoirs –which is precisely how we learn about the background before the series really gets going.

Not long after the first episode begins, something unexpected happens that sets the story in motion: Conan discovers a girl with braids and a red dress lying unconscious on the beach. He runs to fetch his grandfather. They don't know there are other humans left on the planet; Conan has never seen a girl before.

Conan, el niño del futuro also shares with Robotech a strong element of journey, search and adventure. His quest is driven by his grandfather's advice: "Go on and take care of your friends".

So Conan builds a small boat to go in search of Lana after she's kidnapped by soldiers. The girl can speak telepathically with her grandfather, who happens to be the last scientist who knows the secrets of solar energy –and his knowledge is necessary to start up the war machine of a country called Industria, ruled by a dictator with imperial ambitions, Lepka. Lana is taken away by force, and in his attempt to save her, Grandpa is gunned down.

Conan is left alone on the Lost Island, and that's when he realizes he can't stay there: he has to go and look for his new friend. Using pieces of the crashed rocket, he builds a small craft that takes him to another island where he meets his first friend, Jimsy.

One of Miyazaki's defining qualities throughout his work is his ability to recreate small details that give his characters a unique sense of humanity. When Conan meets Jimsy, for example, the boy offers him a smoke –different times– and Conan accepts. Watching the series again as an adult, I realized the key detail isn't that he coughs; it's that after smoking, their eyes get all squinty and, like that Leonardo DiCaprio pointing-at-the-TV meme, I thought: "This kid is smoking weed!"

That same night, Conan wakes up to pee and, after he finishes, he shivers in that way we all do after urinating. I've never seen that detail in any other series. It gave the show a kind of humanity that's hard to forget.

A Future That Never Came

If I keep describing the series and what I felt in each episode, this article will never end. I'd rather focus on something I like to emphasize to those of us who consume science fiction –especially predictive futurism– which is that the only future we can be truly sure of is the one that has already become the past.

As a kid, I imagined the world would turn out like Robotech, obviously– all of its technology fascinated me precisely because it didn't exist. "I have to be ready, because life is going to be like this", I thought at eleven. Clearly, no alien ship crashed in 1999 and there are no planes turning into giant robots.

There's a scene where Rick Hunter is sitting on a bench when a robot-public-phone rolls up to him, repeating "Call for Rick Hunter" until it finds him and he can answer. For me, that was mind-blowing: super ultra-futuristic. Now I find it kind of ridiculous –of course we had no idea about the internet or mobile phones back then. We always watch old futurist series with the benefit of hindsight, as they say in politics: we're reading them with Monday's newspaper in hand. Futurism inevitably turns into retrofuturism.

The catastrophe of 2008 never arrived either, as in Future Boy Conan, and so far solar energy has been more of a solution than a problem. There are no sunken continents, although the oceans are rising. But is it "being right" about the future that gives series like these their value? Of course not. In these cases, their value lies in the quiet message that, whatever happens, cultural aspects of humanity –solidarity, mutual support– are what can keep us alive as a species.

There is another scene in Conan that moves me deeply. He is trapped in a block of iron that drags him to the bottom of the sea. Lana speaks to him telepathically, begging him to hold on. She takes a huge breath and swims down to where he is, sharing her oxygen with him mouth-to-mouth, again and again. It is the most profound act of love and the only kiss they share throughout the entire series –a kiss that literally saves Conan's life. I go back to that episode whenever I can; it makes me feel good, it's a little jolt of pure satisfaction.

Most of the people reading this have probably never seen Future Boy Conan. In Argentina, you can watch it on a site called animeflv.one; it's also available on Prime Video in some Latin American countries –and if not, some pirate will surely have uploaded it somewhere. It will do you good to watch it or show it to someone else. Robotech is on Netflix. Both shows give me a sweet nostalgia, an indelible image of a future in which we would triumph and build a better world –a future that, thankfully, never arrived, even if we don't like our present all that much either.

Telling a story is just the excuse. Using the forms of science fiction –or any other narrative genre– is nothing more than a vehicle for talking about other things; in this case, profound ideas aimed at very young children who, crucially, were not underestimated. These series made us feel taken seriously: they trusted that we could handle complex stories, with the human condition pulsing in every episode; that adventure has a cost; that childhood is not naïve.

I'm grateful to have been their contemporary, and I'm just as grateful that I can still watch them whenever I want and show them to more people. Go watch them –they're invaluable.