I've been getting a lot of messages with the same request: "Juan, put together a reading list". I could point everyone to my Goodreads page, but readers don’t just want a list —they want a reading guide. Ambitious people looking for a bit of avive —Argentine slang for savvy, insider know-how. Well, here it is.

This is not a complete or exhaustive list of the entire genre but more or less maps out my reading journey through science fiction. It is clear that there are others, none is better, each one stands on its own. It is what it is. In my view, the term "science fiction" doesn't quite fit —it's more like an extension of fantasy, with a touch of horror and philosophical speculation. On the other hand, they are not only novels, there are also stories.

This list expands on what I call "the Canon", my ongoing map of essential stories across media, from film to literature, with a general concept of a type of "story" that particularly catches my attention. In short, the search is the same, and if for some reason I postponed making a list like this quite a bit, it is because I wanted it to be well integrated with the rest.

Personally, I feel that science fiction literature is also connected –and perhaps can even be understood as an expansion– with the fantastic story in the terms in which Tzvetan Todorov defines it. That's not the official definition of science fiction —if such a thing even exists— but in my reading journey, both worlds are deeply connected.

The comings and goings of the genre take us and bring us again and again rediscuss the limits. This is what has been happening for a few years with the "new weird" publishing label. Sometimes it sounds like we are reinventing the wheel. Sometimes it doen't. Anyway, here we go with the Canon.

1 - The Bible (10th Century BC - 2nd Century AD)

Yes, it seems obvious. But, buddy, you have to read the Bible. Beyond the fact that it is the wisdom book par excellence and on the historical religious side, it has its own value as a reservoir of stories that endured some 5,000 years of selective pressure. Was it the only book? No. However it survived, it was copied, it exists before the book concept. Skinny, it's like having a spell book in your hands. Eden, Cain and Abel, the tower of Babel, David vs Goliath, Samson, the fall, the exodus, the pharaoh. YOU FUCKING NAME IT. If you don't read this, you are giving away HANDICAP.

2 - Frankenstein (Mary Shelley, 1818)

The book that started it all. The first Gothic story where a scientific motivation generates an immense problem. That is what, even today, a large part of science fiction is about –in my way of seeing things, the most interesting– that remains coiled in the premise that "invention bursts the inventor". Yes, it is a rereading of Genesis. That's why you have to read it.

3 - Complete Stories (Edgar Allan Poe, 1831-1849)

Edgar Allan Poe is the greatest thing there is. He is the master of the story. A machine for inventing turning points, introducing terror into everyday life and creating the gothic atmosphere that plunges the reader into the constant question of what it is real. The master of the fantastic. That's why I can't choose, you have to read everything. If you don't know where, start with "Berenice".

4 - The Hound of the Baskervilles (Arthur Conan Doyle, 1902)

They should be here The Time Machine and The war of the worlds by HG Wells, but I didn't read them. You can't do everything. Instead, I grab some of the best of Conan Doyle, who dares to play strap-on with the fantastic to then build the most rationalist exit at hand possible. Reading Conan Doyle makes you think about that mental machinery that is a story, how the characters can know more (or less) than the reader and that the detailed and obsessive construction of a piece of watchmaking has a reward.

5 - Complete Works (H. P. Lovecraft, 1917-1937)

Very soon we will have an exclusive note from Dante Sabatto about the genius of Providence. But the same thing happens with Poe. He is a master of the short story and on top of that he develops a type of horror that is indifferent to human existence. The human is a speck of dust on the back of a Carnotaurus. Topics that we are going to find again and again throughout the history of science fiction. Mandatory material. Non-negotiable.

6 - Complete Works (Jorge Luis Borges, 1923-1985)

The same as with the other two masters (Poe and Lovecraft) but on top of that Argentine. As Robi Roganovich said, in the 40th century people will continue talking about Borges. If you don't know where, start with The Aleph. "Tlon, Uqbar Tertius" is possibly the best Argentine science fiction story ever written.

7 - Brave New World (Aldous Huxley, 1932)

The first of the "dystopias", a world where propaganda, state control, the Fordism model and personal modulation through drugs (soma) replace systems of repression. A classic, a gem, although slightly boring to read.

8 - Star Maker (Olaf Stapledon, 1937)

Book with a prologue by Jorge Luis Borges. A novel about consciousness as a universal vehicle. The possibility of a galactic mind integrated into millions of consciousnesses fighting not to die before the Big Crunch. Total and quite unknown gem.

9 - The Martian Chronicles (Ray Bradbury, 1950)

Second and last book on the list with a prologue by Jorge Luis Borges. Possibly the best book of short stories and the best writing of the genre. A monumental work, an immovable literary piece, in which Bradbury tells the sad and annihilating sequence of man's attempts to colonize Mars. And what that implies.

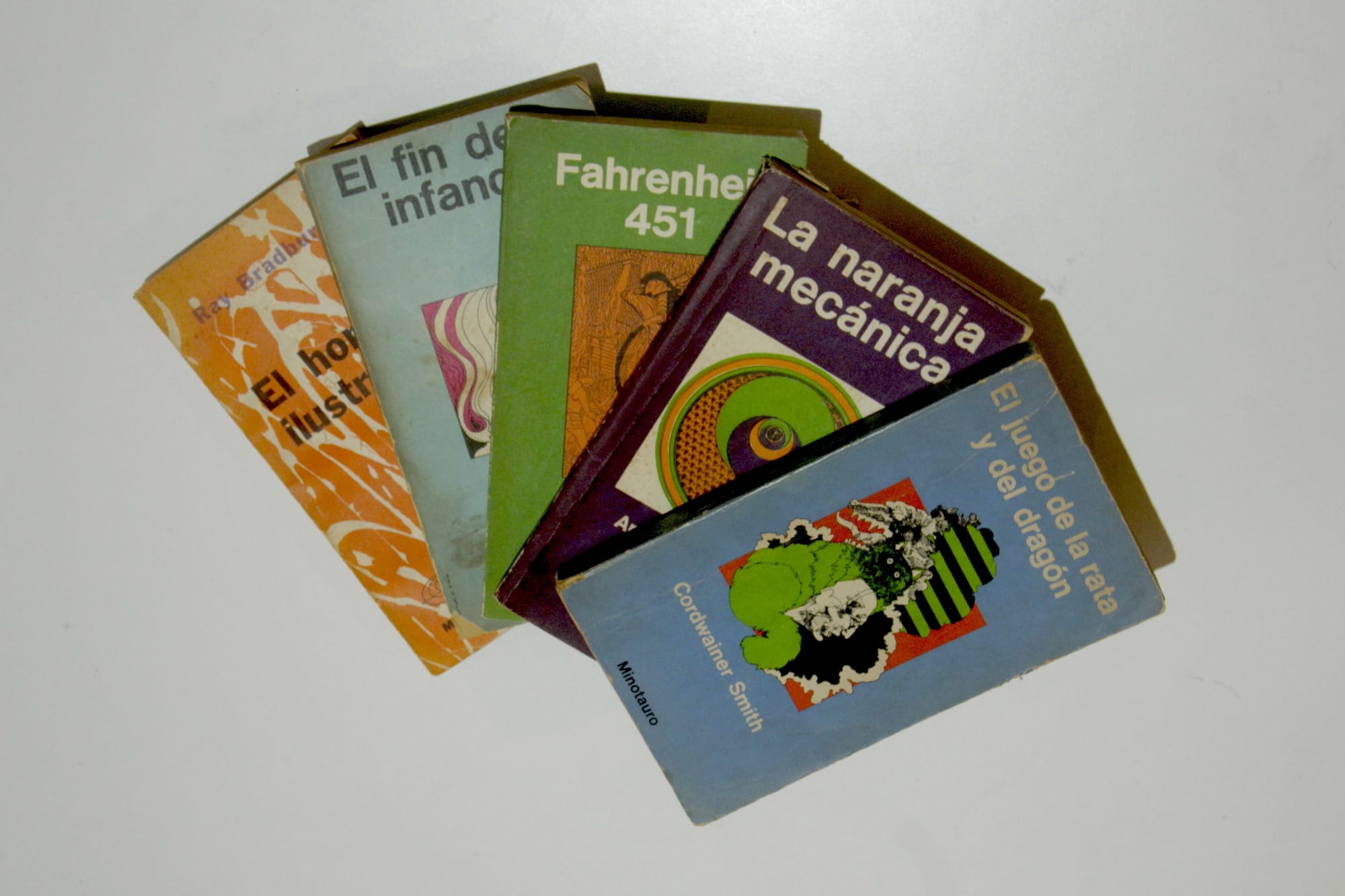

10 - The Illustrated Man (Ray Bradbury, 1951)

Another great book of stories, but no longer in an integrated register behind the same theme but one that varies according to the story. One of the best written of the entire genre. It's really difficult to beat Bradbury. It's simply very good. I recommend "The Long Rain", a planet where it never stops raining. Sublime.

11 - Foundation Trilogy (Isaac Asimov, 1951-1953)

Another of the heavyweights of science fiction. Far from Shelley's more pessimistic vision but incorporating, on the human level, Stapledon's notion of historical processes of cosmic temporality. The Foundation trilogy tells the story of Hary Seldon, who invents psychohistory, a science that allows us to predict human behavior over time with mathematical models. And try to lessen the imminent destruction of the galactic empire. I also read about Asimov in his role as a popularizer: Of numbers and their history and The history of the Roman Empire. Pounds.

12 - Childhood's End (Arthur C. Clarke, 1953)

The whole idea that humanity will eventually evolve into another type of life form was born here. Guided by the Overlords (literally demons) who arrive on giant ships simultaneously on Earth, humans reach a new state of consciousness.

13 - Fahrenheit 451 (Ray Bradbury, 1953)

Bradbury writes his own version of 1984. Actually an answer. For Bradbury, the main threats to the ideal of postwar American enlightened society focus more on mass entertainment (people aspire to have their living rooms covered in screens) and social apathy than on coercive state control. Along with A happy world they are a kind of classic trident of science fiction dystopia.

14 - The Lord of the Rings (J. RR Tolkien, 1954-1955)

The masterpiece the greatest of all. The modern fable. The modern fantasy world. The resurrected myth. The adjectives fall short. Why here? Because if the One Ring were a microchip, the story could easily be in the future. It has everything a fat person needs. In particular, the world united by its own mythology that is years and years old.

15 - The game of Rat and Dragon (Cordwainer Smith, 1955)

Total gem. Compilation of stories made by Editorial Minotauro by one of the least read authors of American science fiction and one of the best. Cordwainer Smith is the pseudonym of Paul Linebarger, educated in China as the son of a diplomat, and who worked for many years in the Psychological Warfare section of the North American army (and later the CIA). Unmissable. Only for connoisseurs.

16 - The Eternaut (Héctor G. Oesterheld and Francisco Solano López, 1957-1959)

Founding text of national science fiction in a popular tone. Extraterrestrial invasion, shootings on the River field, wars against the managers of the genocide (the Hands). Even if the series is already on Netflix, be sure to read the original.

17 - A Clockwork Orange (Anthony Burgess, 1962)

Senseless adolescent violence turned into a book. The author invented an entire language for the novel and strictly respects it. Difficult to read for that reason, but highly recommended before your 20s.

18 - Hothouse (Brian Aldiss, 1962)

Aldiss proposes that the human brain is actually a parasite and that after a high-intensity solar storm it abandons the human to seek refuge in another form of life. The animals that grow in that new world are all made of plants. At times bizarre, but at the same time with a good dose of smart picks.

19 - The Man in the High Castle (Philip K. Dick, 1962)

Philip K. Dick's first uchronia and introduction to the metaphysics of suspicion. That he is crazy or overdid drugs or has a level of paranoia not compatible with being half a junkie and living in the United States. The Third Reich won the war and this is the history of the United States in that world. To the angle.

20 - The Cyberiad (Stanisław Lem, 1965)

Masterpiece. Trurl and Klapaucius are two universal engineers who travel the planets and galaxies providing their problem-solving services to a plethora of useless people. Top of the range, high-flying philosophical humor. In "How Trurl Built a Dragon" they invent a "probabilistic dragon". You have to close the stadium.

21 - Dune (Frank Herbert, 1965)

The space epic of all time. Set in a primitive future and around a drug that drives the planetary economy, Herbert "spice" is dispatched with one of the most iconic works of the genre.

22 - Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (Philip K. Dick, 1968)

Dick's Neoplatonic suspicion that the world we see may be a hoax is beginning to take shape. It tells us about a day in the life of Rick Deckard, a bounty hunter who heroically manages to value five replicants (androids exactly the same as humans) and thus finally be able to buy a real sheep.

23 - Ubik (Philip K. Dick, 1969)

The complete culmination of Neoplatonic paranoia. The entire world seems to be entering a factual decline that takes it until the '30s. The only thing stopping him is a spray sold on television: Ubik. Masterpiece.

24 - To Your Scattered Bodies Go (Philip José Farmer, 1971)

After death, all humanity –from all times and places– is resurrected naked on the banks of an endless river that runs through an unknown planet. Among them, Herman Goëring. The premise evolved into a saga that I did not read in its entirety. I recommend.

25 - The World for Word is Forest (Ursula K. Le Guin, 1972)

Avatar, by James Cameron, it's a complete robbery. Beyond that, Le Guin's book is genuinely good, short, and written like the gods. It's worth reading and you save yourself all of Cameron's delirium, Dance with wolves, The last Samurai and Pocahontas.

26 - Carrie (Stephen King - 1974)

A punch to the gut. It's not exactly science fiction, but it connects with Akira and stands among the best books I’ve read by King.

27 - The Silmarillion (J. RR Tolkien, 1977, posthumous)

The mythical construction of the Lord of the Rings. That which sustains the world of Middle-earth and makes it feel alive. Watching a fictional world age through the centuries is an experience as sad as it is moving.

28 - The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (Douglas Adams, 1979)

Cyberiad but with cheddar. I read this one before and I loved it. Then I read the other one and understood that it was kind of nonsense. Still, it's a nice sci-fi satire. Enter something from that record. No, well that was already in Cyberiad. Cyberiad with Bald Eagles.

29 - Kalpa Imperial (Angélica Gorodischer, 1983)

A must-read. Monumental work of the emblematic author of Argentine science fiction. Prologue by Le Guin for its English edition. Same mambo as Cyberiad as for a half-joking tone, but with some of the Silmarillion-Foundation in this matter of counting eons of empires. Beautiful short stories.

30 - Christine (Stephen King, 1983)

A killer car. We repeat, a killer car. In what could later be called "New Weird", King brings the idea of the possessed to a vehicle. From the haunted castle to a 1958 model Plymouth Fury. A friend gave it to me for a birthday and I thought it was a joke. It was my entrance to Stephen King. The film was directed by John Carpenter.

31 - The Werewolf Cycle (Stephen King, 1983)

A tiny town. A werewolf. Four seasons. A little boy in a wheelchair. That’s all I’ll say.

32 - The Colour of Magic (Terry Pratchett, 1983)

Beginning of the saga Discworld by Terry Pratchett. A kind of parody of everything that is taken more or less seriously on this list. The Discworld is a flat world supported by four elephants that travel on the shell of a star tortoise called Great A'Tuin.

33 - Neuromancer (William Gibson, 1984)

He invented Cyberpunk. Anticipated the internet. Period book. I agree that it is a bit of a hassle to read, but it is one of those that you have to read no matter what. Much of everything is here.

34 - The Hellbound Heart (Clive Barker, 1986)

Clive Barker puts together a quasi-Lovecraftian mythology on a tile. It came to the screen under the name of Hellraiser and it positioned him as one of the most popular authors of his time. Also included in the New Weird anthology.

35 - Good Omens (Neil Gaiman & Terry Pratchett, 1990)

Two titans of the genre. An angel and a demon collaborate in an illegal way to stop the arrival of the Antichrist and prevent the destruction of the world. That is, let's say, the Apocalypse.

36 - Snow Crash (Neal Stephenson, 1992)

Pure brilliance. Cyberpunk, world in layer two (metaverse), digital currencies, but most important of all: a theory of language as a virus and the possibility of conjuring magic with it. A world disintegrated into micronations where the best paying job is the buying and selling of archived information from an already extinct world. Supreme Revival, mention of the Sumerians and Enki. A real gem.

37 - Perdido Street Station (China Miéville, 2000)

It does not inaugurate but encodes the "new weird". China Miéville deploys all the possibilities of fictional worlds without anthropocentric restrictions. Science fiction/Fantasy/Weird deconstructed. Top of the range and inspiration for a lot of things that came later. The city as a world in itself.

38 - American Gods (Neil Gaiman, 2001)

The best of Gaiman I dare say. An underhanded mythology in the world of ordinary people. Harry Potter style but a little less childish (I don't know if that much). Great travel novel through the United States. An ode to 20th century immigration.

39 - Plop (Rafael Pinedo, 2002)

The best work of fiction about primitive futures in Argentina. All the stories of the Fierro (an Argentine magazine) condensed into a single book. A masterpiece. No turns.

40 - The Three-Body Problem (Liu Cixin, 2008)

Chinese science fiction. Beginning of trilogy. A masterful first chapter. The rest frays a little. They say it raises a lot in the following books. We'll have to see. Even so, it has a good story, there are aliens (but not as one thinks). You have to read it, it is contemporary.

41 - The New Weird (Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, 2008)

Work that codifies the "new weird", something like a label that is half marketing, half editorial for a wave of writers not so classifiable in classical definitions. Michael Moorcock, China Miéville and Clive Barker, among others.

42 - Bodies of Summer (Martín Felipe Castagnet, 2012)

vernacular science fiction with speculation about what life would be like if consciousness could be uploaded to a server and reinstalled in a body. A modern classic.

43 - There Is No Antimemetics Division (QNTM, 2020)

What would happen if objects or beings existed with the property of not being remembered? That is, anti memetics. This work is founded on this premise and on the work done by the collaborative fictional website of the SCP Foundation. I finished reading it a few days ago and I'm still fascinated. In the same line of Snowcrash, memetic science fiction.

EN

EN