"What I'm most afraid of is still not knowing the difference between the real world and fiction."

Keiichiro Toyama, director of the first Silent Hill, in an interview with TheGamer, August 2024.

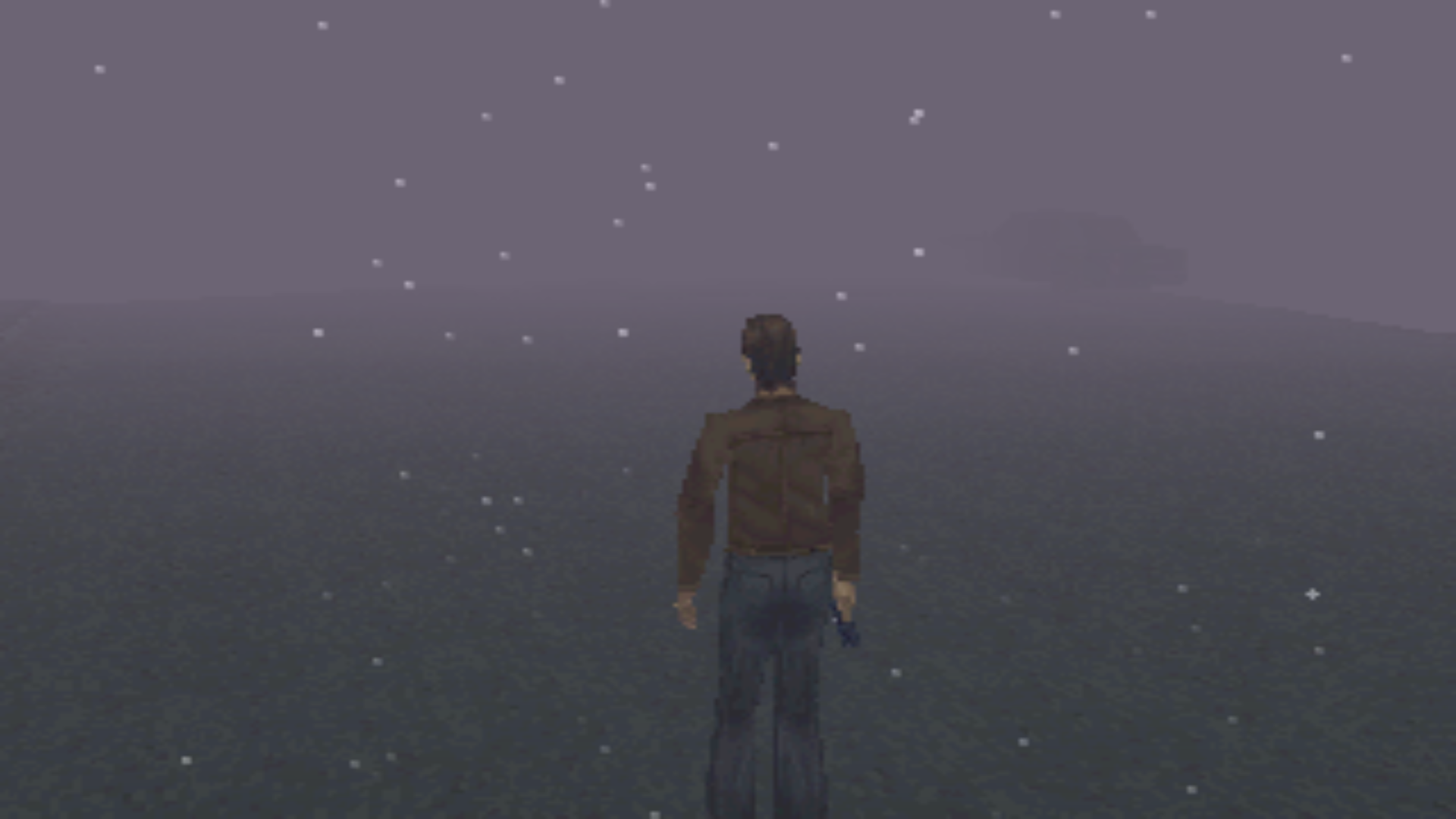

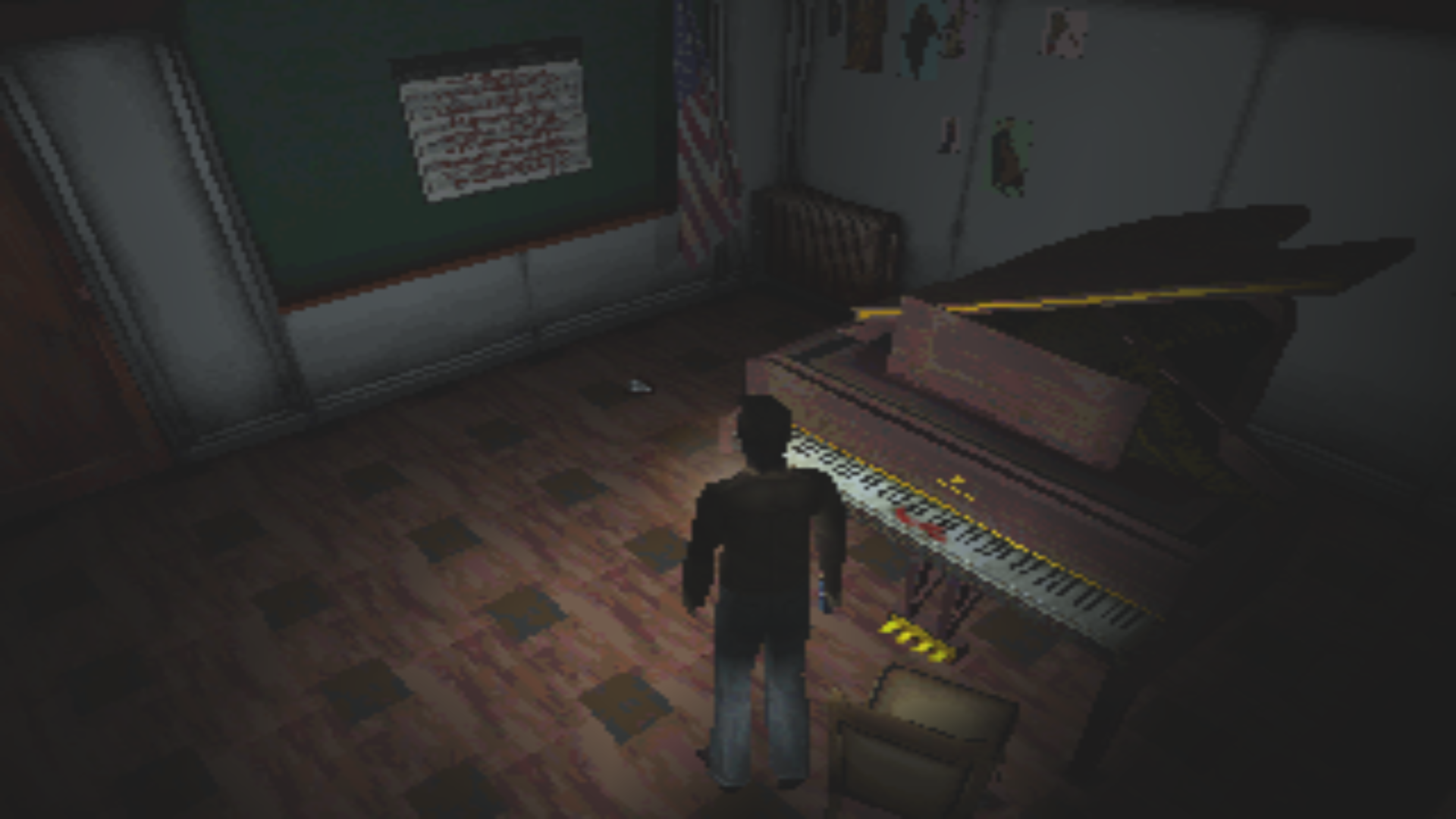

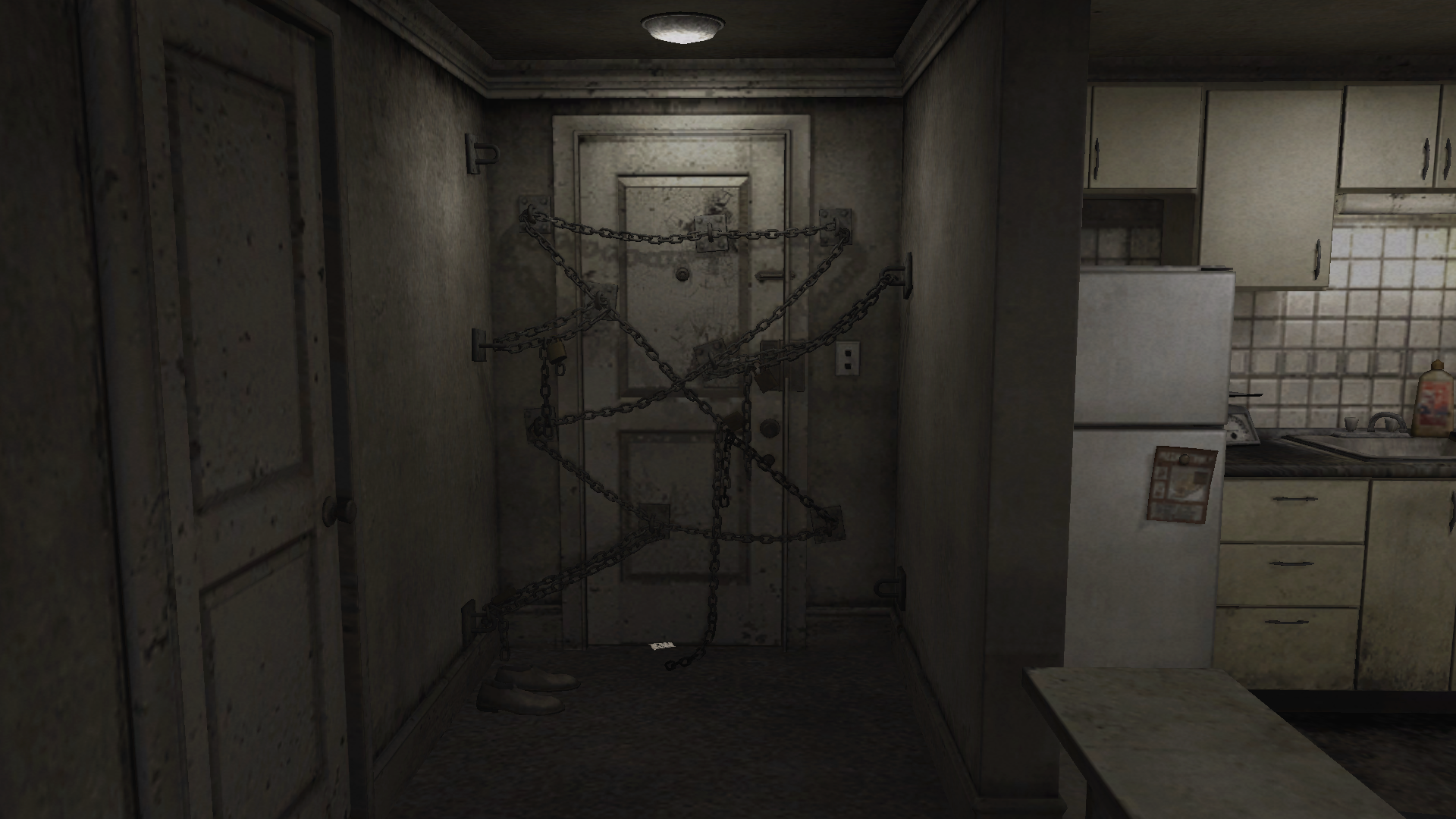

A father sees a strange figure on the road, crashes his car, loses track of his daughter and walks into a town to look for her. Another man rereads, with sadness and disbelief, a new invitation from the woman of his life, who has been dead for years. A young woman explores a creepy amusement park without knowing how she got there, until she wakes up in a shopping mall minutes before something inexplicable happens. The scruffy Henry has a nightmare about his apartment, gets up, and discovers that everything is still the same: he remains trapped in his cramped place, the door covered in padlocks and deadbolts, with no way out.

Between mysterious characters, dreamlike worlds and purgatories filled with inconceivable creatures, the different entries in the Silent Hill series unfold. Originally conceived as an adaptation of Stephen King's novel The Mist, the first game came from a group of Japanese developers with uneven résumés. The legendary Konami wanted its own horror title after the success of Capcom's Resident Evil in 1996, and this team would do everything it could to deliver it.

Steeped in the boom of the unknown, cults, paranormal stories and even Nostradamus-style prophecies, a large part of the Japanese public embraced these topics while the country was going through major technological changes and a long deflationary stretch that would come to be known as the "lost decade". The group popularly nicknamed "Team Silent" fed on all of this, on Western cities and imagery as well as films like Jacob's Ladder (Adrian Lyne, 1990) and Hellraiser (Clive Barker, 1987), to conjure up a cursed work that would change the industry forever.

What Happens in the Silence

While other franchises put most of the focus on monsters and the creatures you have to fight, the minds behind Silent Hill decided to center the characters, the environments and the town/dimension/state of mind –whatever it is– that gives the series its name. Of course, Silent Hill would be nothing without its abominable enemies, but they tend to be reflections of the fears, desires and suffering of its protagonists.

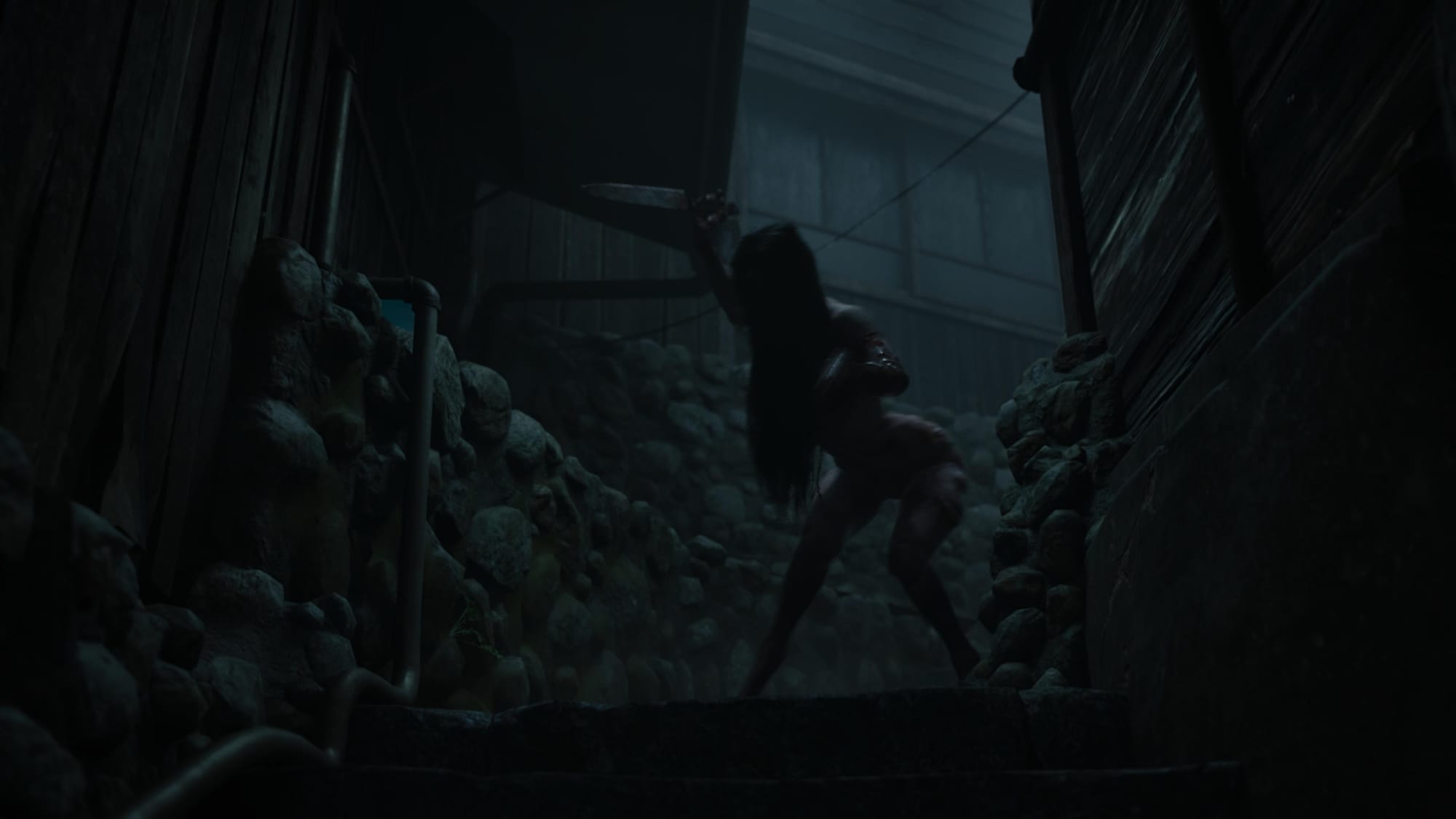

Protagonists like James Sunderland (Silent Hill 2), who receives a letter from his wife Mary inviting him to meet her in Silent Hill. The problem is that Mary died years ago from an illness. Even so, curiosity wins out, and James explores the town in search of answers, running into characters with various psychological issues: victims of abuse, delusional personalities, dangerously hostile people. Along the way the town –or is it James?– shifts, and we discover "Otherworld" versions of areas we've already explored, with alternate layouts that embody filth, rust and things that can't be fixed.

These spaces are infested with creatures whose designs we begin to link to James's fears and anxieties –his repressed sexuality, the traumatic experiences of secondary characters, and more. When we're not being hunted by them, when we're supposedly in moments of peace and absolute silence, that's when the real, insidious terror is doing its work.

Part of the greatness of Silent Hill as a series lies in how moving through its locations doesn't just feel like entering and exiting sets, but like peeling back the layers of a human mind. Our protagonists are disoriented, sometimes even discovering who they really are or what they've done. And despite their different appearances and ways of expressing and reacting to what just happened, they all share one thing: they suffer. To a greater or lesser extent, they're suffering all the time. Even the puzzles tend to be closely tied to that suffering.

It's not a series defined by jump scares –though it does have some great ones– nor by its combat (which at its best is "functional", deliberately so), nor simply by the grossness of its enemy designs, but by the stories we gradually unpack, the countless details open to interpretation, and the feeling that we are walking through our characters' private hells.

What the Fuck Is Silent Hill?

"Is Silent Hill a real town?" is a question with no definitive answer. It also depends on which game we're talking about, because although the first four entries clearly explore the inner lives of their protagonists (and sometimes secondary characters, like Alessa in the first game), there is also a cult in this universe –except in the second game– that carries a lot of narrative and thematic weight.

Even so, thanks to its transitions that ignore all logic, the stilted, unreal exchanges between characters, and the way our protagonists wake up in places they've never been after inexplicable events, we can think of Silent Hill as something more than a specific physical location. It's a place that exists and doesn't exist, a passage between worlds and sensations, a manifestation of our own cognitive capacities. And that's what's truly terrifying. Because we can escape from a place, but we can never escape from our own mind. Except, obviously, in death.

Can Suffering Be Avoided?

When I was five years old, I had suicidal thoughts for the first time. I don't remember what we were arguing about, but the argument ended in something I wasn't expecting: my mother crying. She said something to me, turned around and locked herself in her room. We'd had some intense fights before, but it had never ended like that. It threw me off completely. A pain gripped my chest and quickly spread through my body, leaving me frozen for a moment. I began to tear myself apart inside, saying things no creature should ever have to think.

When I got control of my body back, I opened a drawer and grabbed the knife my mother used to cut meat. Slowly, without hurry, I began tracing the veins of my right arm, parallel to them. I pressed the blade down with a kind of delicacy I didn't know I had: I never actually cut myself. I just kept skimming the surface, wondering whether I was going to take that step or not.

My fascination with horror came in my teens, when I wasn't quite as scared of everything anymore. I started reading books (King, Barker, Lovecraft), watching movies (American, Italian, Japanese) and, of course, playing video games (Resident Evil, Fatal Frame, Silent Hill). At first I was chasing the most primitive things: I wanted to be scared, to feel fear and disgust. Over the years, that impulse got more refined. I realized horror is for much more than scaring you; in fact, whether a horror movie is "scary" is almost secondary.

What's special about the genre is how it takes the fears and anxieties of its creators and their times –often the same or very similar to ours– and turns them into something both beautiful and macabre. These representations let us think and feel our problems in ways we would never have been able to experience otherwise.

Silent Hill occupied –and still occupies– that place in my life. Its games, along with so many other works, helped me connect with my ideations and the voices in my head in a different way. A more curious, understanding and above all gentle way, if you like. It's not that I stopped having dangerous thoughts; being a teenager, they only grew stronger. But in fiction and in the fog, I could see other colors.

The theoretical framework would expand years later, with my degree in Psychology and, more recently, with my study and research of ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy). This clinical model, unlike the better-known ones, doesn't treat suffering as a failure or a problem to be fixed: suffering is normal, expected, and accompanies us throughout our lives. We don't live in a constant state of happiness; our "normal" is shot through with psychological processes that cause us pain (Hayes et al., 1999). Learning how to live with them is what allows us to have the kind of life we want.

The Present Respects the Past but Points to the Future

Everything I've written so far about Silent Hill has been about the series in general and what I feel it brings to the table, but when I talk about the games themselves, directly or indirectly, I'm always talking about the first four. After Silent Hill 4: The Room (2004), the series went into a downward spiral worthy of its own characters: games ranging from mediocre to outright terrible, and many years of silence while Konami seemed to be abandoning traditional gaming. The characteristic silence of the series started to feel permanent.

Only a few years ago, with a flurry of announcements, a sort of rebirth began. A remake of Silent Hill 2 –failed, in my opinion–had been the best-received attempt up to 2024, after disasters like Ascension and The Short Message, whose gameplay ideas and stories were pathetic: fetishizing everything that made the IP unique without managing to create characters you could connect with on a deeper level.

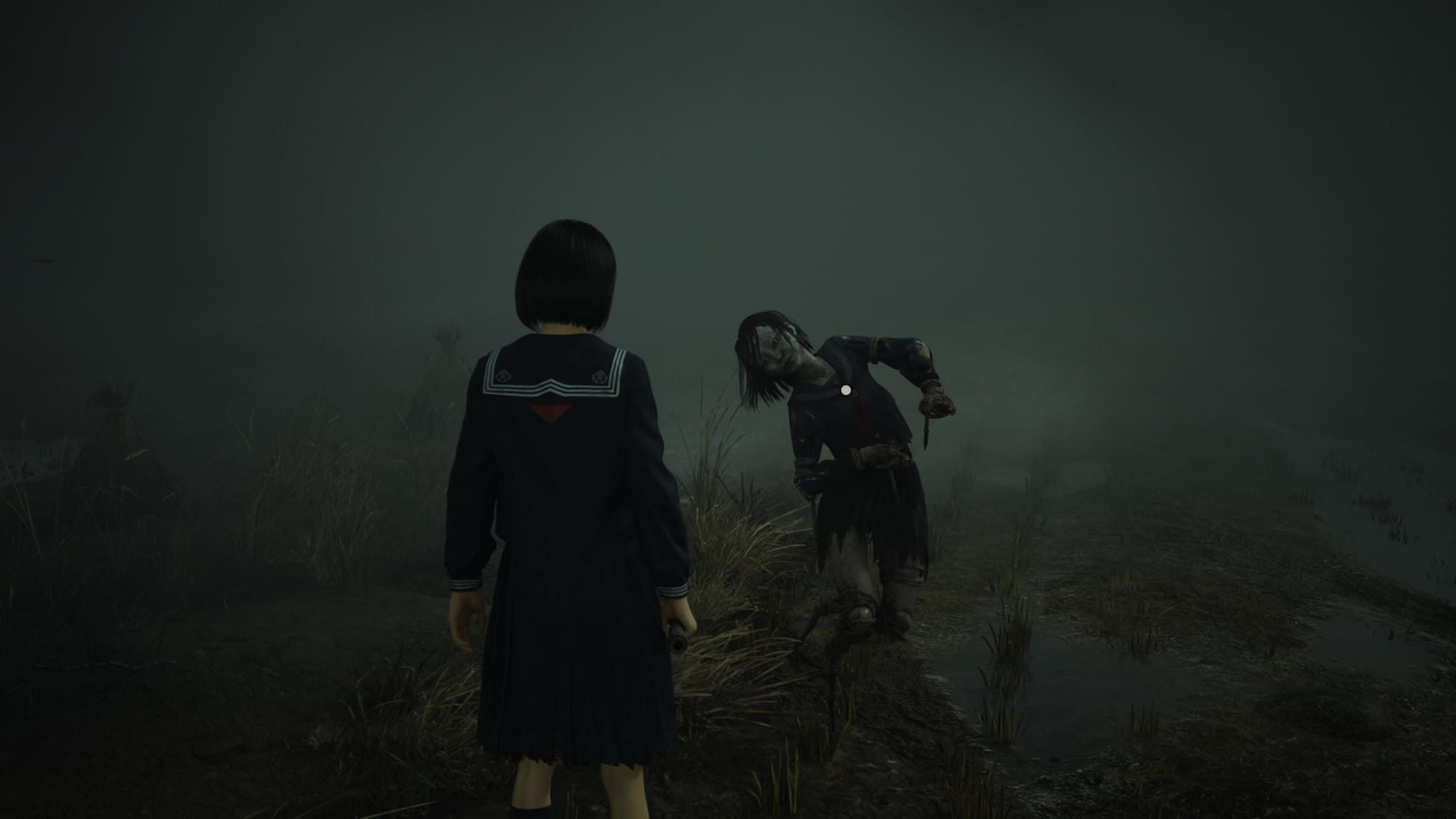

Fortunately, this year Silent Hill f broke the streak. The latest entry from NeoBards Entertainment, written by the iconic Ryukishi07 (When They Cry), gave us a game worthy of the series at its best. For the first time, oddly enough, the story is set in a Japanese town, leaving behind the more Western-looking streets and buildings to immerse us in the alleys of the country that gave the series life in the late '90s.

Silent Hill f

Hinako Shimizu, a teenager, is the new protagonist. She doesn't seem to have the best relationship with her parents or her friends, and she lives in a time marked by women's social movements in Japan. While Silent Hill f contains all the ingredients we expect from the series –an exploration of the protagonist's psyche, a strong emphasis on atmosphere and environments, fog, other worlds, enemies and puzzles with specific meanings –it's in Hinako herself and in the way her era is portrayed that we find the game's strongest, most original elements.

Every previous protagonist found weapons to defend themselves with, or at least to give themselves a better chance of escaping. Hinako is different: despite her age, her attacks feel more precise and controllable, and she even has special moves. This creates a new feeling in a combat system that had always been clunky and limited, to better represent fear and a lack of options. Those earlier protagonists endured their paths and their suffering, but Hinako resists more actively. It's a shift in philosophy that, far from betraying the series' roots, shows real narrative coherence with its young protagonist and everything she's going through as she grows.

That doesn't mean she's a character without wounds or weaknesses. On the contrary: her distrust of others, her sense that she can't form genuine bonds, and the abuse she endures from authority figures are just some of the elements that show how fragile she really is. She is a daughter of her context, shaped by all the expectations and meanings that have been imposed on her. But she's also someone who, despite everything, fights –and thanks to that struggle and everything that happens, she is constantly reshaping herself as a woman and as a human being.

Downhill

There's more Silent Hill on the way. Announcements like the remake of the original game by Bloober Team (the studio behind the remaster of Silent Hill 2) don't excite me at all, but I am curious about the long-absent Townfall from Annapurna and No Code / Screenburn. And above all, I'm excited by the promise that the success of Silent Hill f will lead to new stories. After many years of silence and hating each new Konami release, I can finally feel interested again in the series that has made me –and still makes me– think so much about that invisible layer of experience that can suddenly change our lives.

There are voices and monsters that never really shut up. The best we can hope for is to tame them. And it's possible. It really is possible.