At 17, I was trying to find a personality. I had already finished high school and wanted to be part of something. For many reasons, one portion of my DNA was very nerdy and the other was just weird, so getting closer to urban tribes felt inevitable. Looking for somewhere to belong, one day I caught my own reflection: green cargo shorts, black hoodie, giant backpack and red cap. At what point did I become a Ninja Turtle? That was the question when I saw myself. That day I started thinking a lot about who I am and who I want to be, and in that process I also realized how I'd been influenced into becoming this mutant who's trying to be a responsible adult but is still trapped in a childhood that refuses to let go.

The Tortugamania of the '90s had a huge impact on the millennial generation, creating an army of devotees who, to this day –now well into their forties– still worship the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. But to understand this phenomenon –which not only shaped personalities but also changed how we consume culture– and how it affected us, we have to start at the beginning. And the beginning was a fanzine.

Teenage, Mutant, Ninja, and Turtles

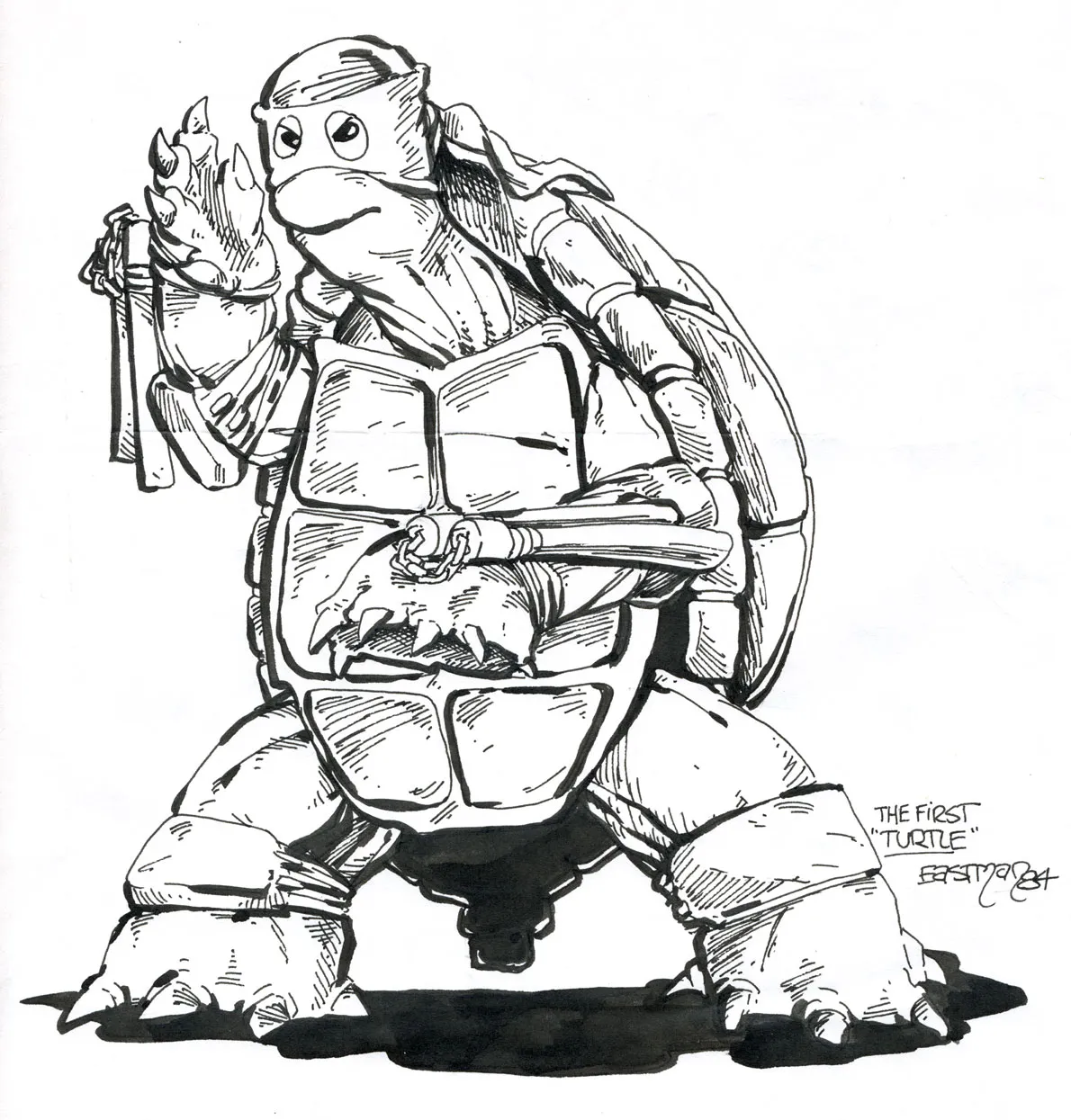

One night in 1984, Kevin Eastman, just goofing around, drew a turtle with a pair of nunchucks and a mask. His friend and partner Peter Laird thought it was funny and created three more, each with different weapons. The joke turned into an experiment, began to make sense to them, and they decided to go deeper with a new logic: take elements from the violent, gritty comics of the time –like Daredevil and Ronin, both by Frank Miller– and mash them up with these absurd characters.

They did a first print run of 3,000 black-and-white fanzines, which sold out very quickly. That fueled demand among comic-book fans, who passed the word around about what they'd just read. This "version 1" of the Ninja Turtles was aimed at adult readers, not only because of the content but also because of the way it was distributed and presented: very underground.

It wasn't until 1987 that the Ninja Turtles we all know were born, through the animated TV series. This transformation happened thanks to licensing agent Mark Freedman, who stumbled upon the comic and saw massive commercial potential in the toy market. These were the golden years of action figures, after the success of He-Man, Transformers and G.I. Joe.

But you couldn't sell those violent, brooding Turtles to kids, so they had to make quite a few changes. Freedman pitched the idea to toy company Playmates, which until then hadn't been particularly big, and they told him that in order to sell the toys they needed an animated TV show. In the process of making that series, the Ninja Turtles left behind the darkness of the comic and started mutating into something different: more colorful and more naive.

Season 1 of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (Nickelodeon series)

And that's how we got Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo and Donatello, the turtles we know and carry in our imagination. The changes weren't just visual: the turtles became "more teenage", more fun, and each one had a clearly defined personality –like a boy band. And as the song goes: "Leonardo leads, Donatello does machines, Raphael is cool but rude, Michelangelo is a party dude". Archetypes you could find in any school or friend group; it was easy to pick a turtle based on who you were or who you wanted to be. Answering which turtle was your favorite was basically an identity test that revealed a lot about you. Honestly, we should still be asking that question.

From that moment on, the Ninja Turtles never really left pop culture. The animated series ran for almost ten years and was followed by another, and another, and another. The turtle offensive didn't stop at comics and action figures either –we've also had several new movies. Post-2000, the franchise cemented itself and reached a level of popularity on par with major nerd staples like Star Wars or Transformers.

The Tortugamania of the '90s

There’s a lot written about why they were such a success, but I have my own theories. There were tons of cartoons, but nothing quite like the Ninja Turtles, especially because of the protagonists. The idea of turtles who are also ninjas was completely absurd, and the fact that they were mutants made them outcasts on top of that. But unlike the crybaby X-Men –it's a joke, I love them dearly– they were usually in a good mood, messing around and eating pizza. That vibe of teen brotherhood was crucial for us to get attached to them.

On top of that, the production around the franchise was blessed: they consistently delivered quality across TV, video games, toys, movies, comics and more. The whole thing went fully transmedia, and in every format they stepped into, they landed a hit. In video games, for example, Konami made one of the best beat 'em ups for arcades and consoles –a game we still play– that became a blueprint for many others, including Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Shredder’s Revenge (2022), which is an absolute banger.

It wasn't just a nice toy line or a cute cartoon: most of their products were genuinely good, and that gave the franchise a constant seal of quality. But we shouldn't underestimate the "Ninja" part of the Turtles. The shinobi phenomenon was huge in the United States and showed up in tons of movies, games and comics. Ninjas had joined the kids' hall of acquired tastes alongside dinosaurs, pirates and cowboys.

After the voice actors said goodbye at the end of the series, the trailer for Evangelion was shown

The world went through its Turtle fever, and each country had its own version of the story. I love telling how the Turtles entered the world of lucha libre in Mexico as inspiration for wrestling characters: there were something like four different Turtle tag teams, with Los Tortuguillos Karatekas being my personal favorites. In Japan, the Turtles had their own anime, but the American series also aired there; and my favorite Turtles-in-Japan anecdote is this: when the anime ended, its replacement in the same time slot and on the same channel was Evangelion. For a lot of Turtle fans, that must have been the exact moment their childhood ended –going straight from sewer adventures to Third Impact.

In Argentina, we had it all. The turtle advance was relentless. We had the TV show El Show de las Tortugas Ninja, where they aired the cartoon but also had a host (Juan Gabriel Altavista) and puppets that had nothing to do with the actual designs. We even got one of the earliest porn parodies: Las Tortugas Pinja, by Víctor Maytland.

And of course, there were the figures distributed by J. Sulc S.A., a local company that manufactured and distributed toys, with licenses like RoboCop and James Bond Jr. But the official Argentine figures quickly got mixed up with a tidal wave of bootleg toys: Turtles Fighters knock-offs or just random green turtles sold loose in unmarked plastic bags. In the early '90s, you could find the Ninja Turtles everywhere. Few children's cartoons were as popular in Argentina.

Me, Turtle

The transformation from kid to ninja turtle wasn't accidental in my case. The Turtles were my first true fandom: if Raphael had said we needed to kill the president, I would've at least considered it –that's how absolute the devotion was. I had a Ninja Turtles birthday party, Turtles shoelace covers, the vinyl record, the action figures; my dad even bought me a real throwing star, triggering a family conflict with my mom, who demanded to know why he'd "bought a weapon for Juanma". All of this happened when I was very young: they were my first comic books, my first memories of going to the movies, the Sega carts brought back from Brazil. And it all came before many of the other things that would go on to shape my life.

Maybe over time I specialized and moved on to works "for grown-ups", but I never let go of my love for nerd stuff. And the Turtles stuck with me, because when I discovered the original comic I was already a teenager. It felt like reviving something I'd loved as a kid, but now with a tone that matched who I was becoming.

There was something about the four protagonists that made them carefree and cool: they rode skateboards, ate pizza, watched movies and, let's be honest, they probably smoked weed. Their adventures were full of references to punk, metal and hip hop. I think you can see where this is going. There's a fat nerd archetype that I belong to and that, in my attempts not to be "just another one", I often fight against. But it's pretty obvious. You know this type: the collector, over 100 kilos, beard, glasses and cap, tattoos, cargo pants and giant backpack. We're clones of those Turtles, even in how we look, and our tastes are theirs –pizza included. And really, why wouldn't I want to be a turtle? They were awesome.

And this is where I usually short-circuit. On the one hand, I think this eternal adolescence we're going through isn't all bad: it lets us enjoy life and gives us a kind of freedom our parents or grandparents never had. For some people, it's also a safe place. And it's a path I connect with art, design and the pleasure of making things –the same energy that lets me write this piece, for example.

But at the same time, I get that we're in a strange moment where culture has become heavily infantilized and, between that and the algorithms that segment audiences for the stuff we now call "content", we mostly end up with either crap or nostalgia. Enjoying the past is great, but moving in permanently fries our brains and keeps us from discovering new things. The hard part is that this infantilization has been weaponized by the industry, and we're pretty much trapped in that logic now. The infantilization is total: it cuts across entertainment culture and also shows up in how we dress and what we eat.

Today, the Turtle in me is still alive, even if I'm no longer that much of a fan or collector. I'm one of those snobs who enjoys digging up weird things, and right now the Turtles are the mainstream –the tip of the iceberg. I recommend diving deeper and seeing what's underneath. Thinking about ourselves and understanding how our tastes shape us is important if we want to figure out who we want to be.

I wanted to be Raphael and, if I think about it for a second, I kind of still do.