The first cigarette you ever smoke always sucks. Like beer, it's an acquired taste. Nicotine has a dual effect: it energizes you, makes you alert, but it can also help reduce anxiety or induce a certain state of relaxation in relation to the world around you. I'm not going down the rabbit hole of "smoking is healthy", because it's unnecessary —and because it's good to accept that something obviously harmful can still be enjoyable, in just the right amount.

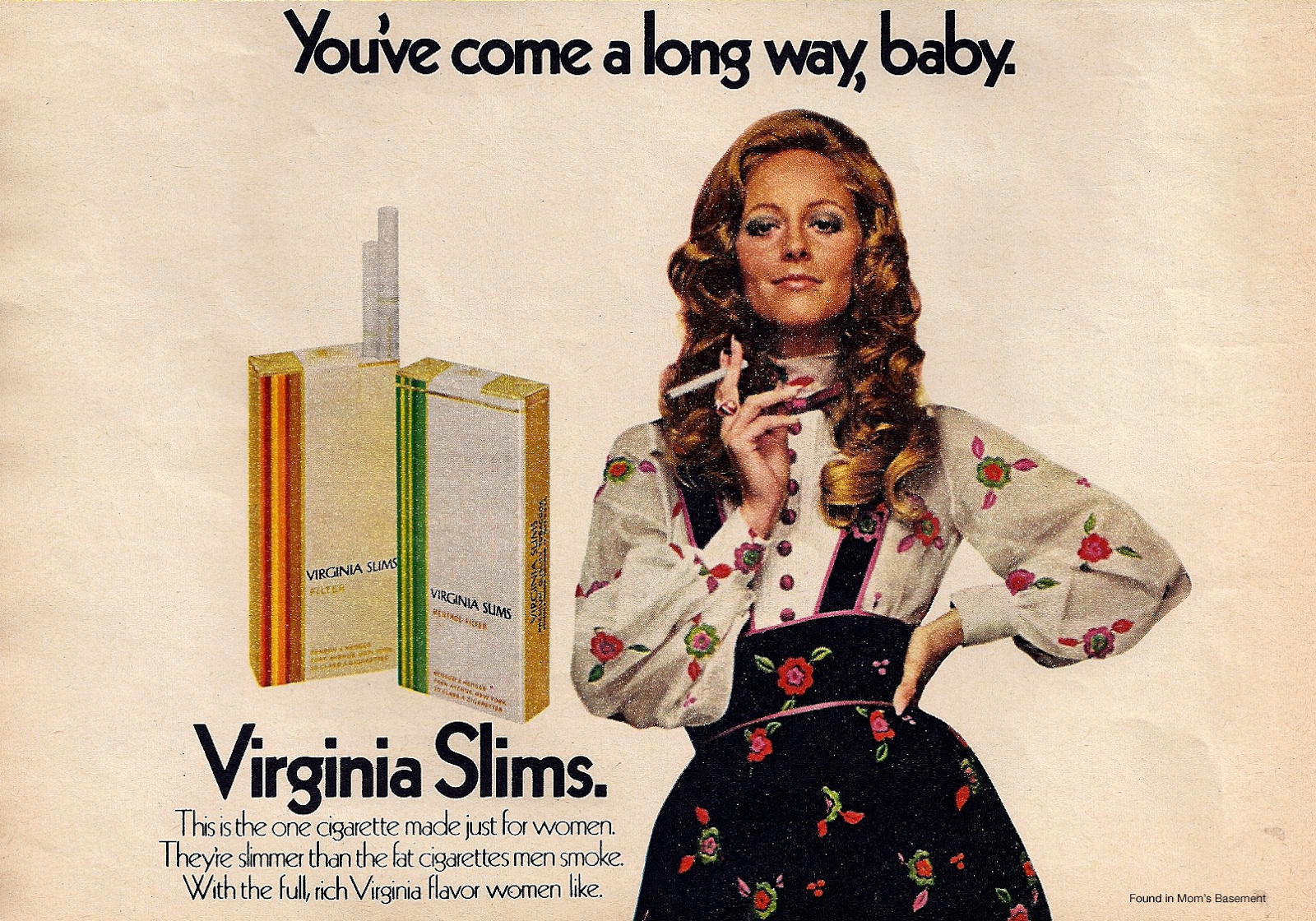

The brands I smoked in my early years were "girly" (Virginia Slims, for example) because they didn't leave as much smell on me or scratch my throat —and because, honestly, I’m kind of "girly" myself. To this day, I choose smoother, more caramel-leaning flavors; since I smoke so little (I don't even hit 10 cigs a week), I can afford pricier packs and avoid cheaper options that are more aggressive on the palate.

Lately, people have handed me packs brought from abroad that make the poor local selection painfully obvious. Marlboro Black 100s, American Spirit, or even weird packs bought in the Barrio Chino show that cigarettes can come with all kinds of flavor variations —and packaging that looks genuinely cool.

Snus also got popular: little cloth pouches filled with nicotine that deliver the same energizing kick without all the tarry garbage that comes from combustion. Personally, I value them because they let me keep cigarettes as "premium air". Not turning into a heavy user is what allows me to keep enjoying not only the substance, but also the social ritual: the after-dinner sobremesa, or "cutting the day" with a quick smoke.

An even more popular offshoot is the whole world of vaporizers —vapers or vapes— which have been key to bringing nicotine into the women's market. Personally, they don't appeal to me: they're designed to be addictive because they come in "tasty" flavors that mask the fact that what you're consuming is, literally, poison —without even getting into the many additives and weird substances that must ride along with that chemical vapor.

The Cig as a Social Lubricant

I've always had an ambiguous relationship with cigarettes. I grew up in a house of smokers; I watched my parents go through two or three packs a day. At every family or social gathering there was a haze of smoke —like a curtain behind discussions about politics and culture. That, plus the fact that I did a lot of sports as a teenager, gave me a strong rejection of cigarettes that sometimes tipped into outright disgust.

But the cig was always there —when people came over, or when I was putting up Schumacher posters in my room. At 16 I tried Cohiba cigars and rethought a few things about smoke. I found a certain taste for it, even if the smell it left on my hands and breath was still pretty unbearable. Then, in my 20s, as I built my own social life, I started to understand its "performative" function: a classy excuse to eject yourself from a boring conversation and go get some air, alone with your thoughts.

Asking for a cigarette —or asking for a light— is also a great way to open a conversation, in a world where (especially for younger generations) that kind of first contact feels increasingly restricted. I always joke that I buy cigs so my friends can smoke them. Between Negroni and Negroni, lighting one up becomes inevitable —a way to stretch the moment. Cigar bars and tobacconists work as meeting points where people bond, and they're one of the last refuges for the privilege of "smoking inside" —a behavior that's now harshly penalized.

Smoking to Farm Aura

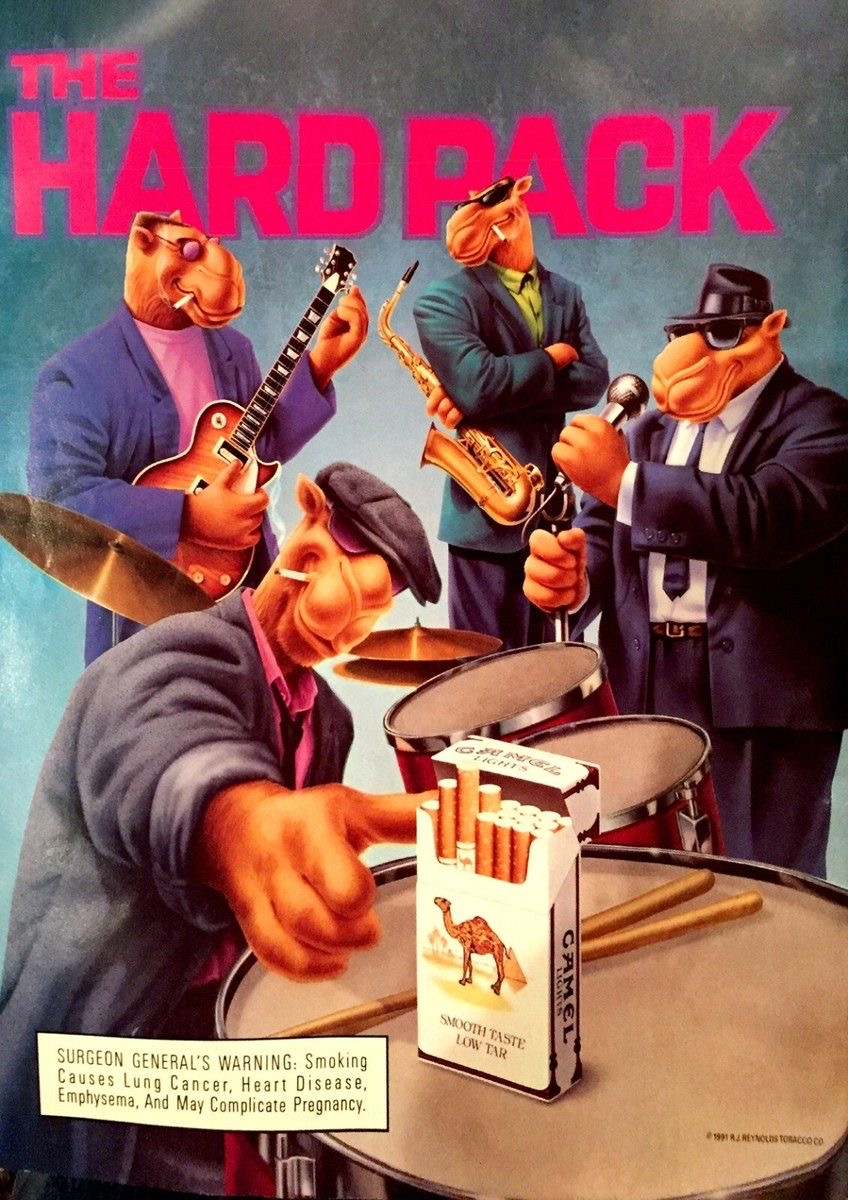

For a few years now, there's been an internet subculture dedicated to "cigarette aesthetics": a cultural vindication of the cig. It's the memory of a time when tobacco didn't face such aggressive social condemnation —when you could smoke indoors, and every seat on a commercial flight came with an ashtray.

Through images of tobacco promo girls on the starting grid of an F1 Grand Prix —Formula 1 has long courted women to sell them alternatives to cigarettes— through photos of major political leaders or actors and actresses with a cig in hand, sensitive young people find an emotional crutch against a world that keeps insisting that everything that makes us happy can kill us.

It's also, obviously, a clandestine marketing campaign, in a context where tobacco companies can no longer sponsor sporting events, advertise in the media, or promote themselves in public space. Against that protective, vigilant impulse of the system (so present since the COVID-19 pandemic), the lost paradise claimed by "cigarette aesthetics" carries a cultural and political edge —one that brings back all kinds of ideas about personal emancipation, vital force, and eroticism.