As a Philosophy student it’s impossible not to bump into the word metaphysics, but it was only when I started playing Magic: The Gathering that I really began paying attention to the idea of meta. This article is an attempt to explain a more colloquial, everyday use of that concept – in particular the idea of the metagame – and sketch out a heterodox way of applying it to daily life. Let’s go.

Aristotle’s Metaphysics

In what used to be known as the Aristotelian canon – that is, all the books by Aristotle that remained within the West throughout history (many were “lost” in the East and would only re-enter Europe centuries later) – there was a series of books at the end that no one really knew how to classify. They were called Metaphysics simply because they came after Physics.

The prefix meta- has that meaning: what comes “after” or “above”. Aristotle’s aim in that book was to investigate “first causes”, meaning the origin of the universe – not in chronological time as we contemporaries tend to think, but rather in terms of its structural ordering. Something like the search for the fundamental laws that govern the universe. That’s what he called metaphysics. And no, it has nothing to do with new-age esotericism.

The second time I ran into the prefix meta- was also at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters at the University of Buenos Aires, in the Introduction to Logic course taught by Alberto Moretti and Eduardo Barrio. In that case we didn’t just study logic, but also metalogic.

While logic, or predicate logic, refers to a formal axiomatic system capable of establishing propositions based on certain basic rules (axioms), metalogic deals with the theoretical justification for those axioms and not others. While in predicate logic we can do something closer to a calculation – for example, “If P then Q; P, therefore Q” (a basic modus ponens) – in metalogic we study the heuristics behind modus ponens and why that pattern counts as a valid form of logical reasoning.

The third time I came across the concept of the “metagame” was playing Magic: The Gathering. Of course.

Richard Garfield’s Metagame

I picked up the notion of metagame in my restless youth, when I wandered through some fairly obscure corners of the internet looking for ways to improve my skills at card games. Magic, the mythical TCG created by Richard Garfield in 1993, had laid the foundations for every game that followed. It was the equivalent of chess. Once you entered that world, everything else felt like party favors. Even though, to be fair, most collectible card games are variations on the same idea.

They’re all some variant of building your own deck of 40 to 60 cards (that number depends a lot on the format), to defeat an opponent playing with their own deck, under some more or less specific win condition: strip away all their life points, deny them a key resource, achieve a set objective, find the card that says you win the game.

The name, setting or IP can change, but in the end the vast majority of classic TCGs are just different versions of Magic. Even if, for some years now, there have also been games that explicitly try not to replicate big brother’s rules.

When I first started playing, back around the year 2000, I dreamed of a definitive deck that could win in any situation and would never need to be updated as new cards periodically appeared. Soon enough I realized that Holy Grail didn’t exist. It was impossible. If it did, every player would already have found it and copied it endlessly. That’s how I stumbled upon the existence of the metagame.

The point is: no one who plays Magic competitively does so “in a vacuum”. Quite the opposite. Every player sits across from someone who has chosen a particular strategy, more or less archetypal. In general, these strategies are strong against some decks and weak against others, which turns the whole thing into a kind of rock–paper–scissors, but way, way more complex.

Think about it: every time you choose “rock”, that “rock” is actually 60 cards, chosen from over 22,000, shuffled together and drawn at random. Same for your opponent.

So knowing the strategy of the dominant decks and the available archetypes in a given context – and using that knowledge to beat others – is almost a basic principle of the game. Realizing this is almost an epiphany. Up to that moment you’ve been playing more or less casually, with cards that look cool or fun (elves vs. goblins, say). The goal is to have fun. But in competitive play, that doesn’t exist. The goal is to win.

Then other strategies appear in response to the dominant ones. Some even try to exploit design gaps opened up by the dominant decks. Choosing which decks to play based on how often each strategy shows up and how favorable each matchup is against the rest of the field is what ultimately produces a metagame.

Aggro, Combo, and Control

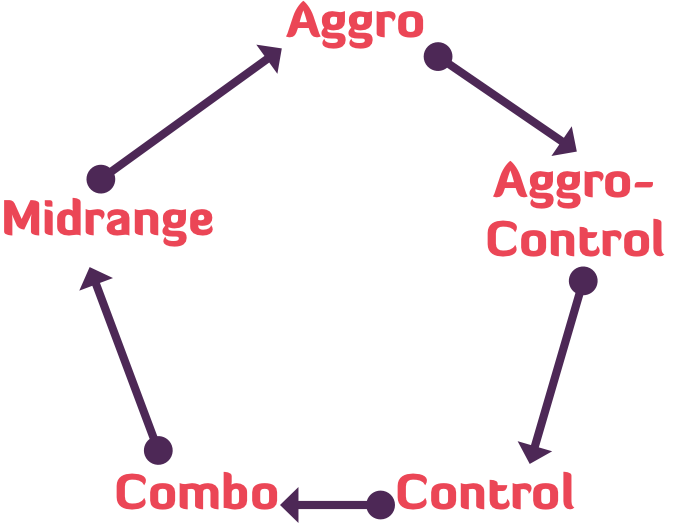

In Magic things seem simple at first, because there are three major strategic families within the enormous space of possible decks: aggro, control, and combo.

- Aggro decks aim to win quickly, with threats that come down in the first turns and burn out fast.

- Control decks try to prevent the opponent from doing anything meaningful and then win in the late game.

- Combo decks try to survive long enough to assemble the pieces of a puzzle (the combo) that generates a synergy which leads inexorably to victory.

Aggro beats control, control beats combo, combo beats aggro. Rock–paper–scissors with extra steps.

When you look closer, hybrid strategies appear: aggro-control, midrange, and so on. In total, Magic ends up feeling like a rock–paper–scissors of five elements, where each strategy beats one but loses to another. Nothing is that simple. Winning decks are the ones that can pivot between two plans of attack: beating the decks they’re supposed to beat, while trying not to lose too badly to the decks they’re unfavored against.

In the end, playing Magic well means playing the metagame well – the one that exists in that specific moment, in that format, at that particular table.

An Expanded Definition of Metagame

In TCGs like Magic, the metagame is the strategic layer that exists above individual games. It’s the space where you decide which deck to play, how to build it, and what risks to take based on what you expect the rest of the competitive environment to bring. Instead of asking yourself, “How do I win this game?”, you ask, “Which deck gives me the best expected win rate against the field?” That’s why people call it “the game above the game”.

The metagame is built along several dimensions:

- Deck distribution: which archetypes dominate, which are Tier 1, and how often you expect to face them.

- Matchup mapping: which decks are favored against which, and how that shapes the internal ecology of the format.

- Technical choices: sideboard cards and specific tweaks within an archetype to improve bad matchups.

- Format speed: whether it pays to play slow interaction, fast aggression, combo, or midrange.

- Expectations: what you think others will play, including second-order anticipation (“they’re going to bring hate against the dominant deck”, “I’ll bring the deck that beats the anti-meta”).

There are different levels of metagame:

- The local meta of a store or small circuit, which can look nothing like the global one.

- The global meta defined by big tournaments, online platforms, and pro players.

- The technical meta, more granular: how many removal spells, how many counters, how many threats.

- And the psychological meta that kicks in at big events, where you try to read how the community will adapt and exploit their blind spots: if everyone adjusts to beat the best deck, you can bring the deck that beats that.

Practicing metagame gives you structural advantages before you even sit down to play. It lets you target the environment’s weak points, avoid dead decks, choose more flexible cards, and plan ahead for emerging trends. The player who masters the meta doesn’t just play good games – they sit down at the table with a deck already positioned to beat the format’s enlarged “mirror”: the other players.

And the metagame is dynamic. It shifts with every tournament, every result, every innovation. A dominant deck generates its own antidote: if the format is ruled by midrange, combo shows up; if combo becomes central, aggro emerges; if aggro gets too big, midrange returns. It’s a continuous cycle, an ecosystem that re-organizes itself every time someone finds an edge.

Finally, it’s important to remember that the metagame is not your favorite deck, nor a fixed list, nor an abstract theory with no consequences. It’s a practical reading of the competitive ecosystem and a constant exercise in adaptation, anticipation, and fine-tuning. That’s where the competitive player really lives: in that layer where every pre-game decision matters as much as in-game skill.

Real Life as a Set of Different Metas

But the metagame isn’t exclusive to Magic and competitive TCGs. The concept spread to every game where strategies, characters, maps, and specific builds clash in a competitive environment.

With the rise of ladders (ranked systems with tiers) in virtually every multiplayer game, the notion of a metagame became essential for anyone who wants to climb to the top. It exists in StarCraft II, LoL, DOTA, Counter-Strike 2, Valorant – basically anywhere there’s competition.

Discovering the concept of metagame led me to wonder whether you could port that idea over to real life. In fact, another article worth writing would be about how videogame languages – especially RPGs – have blended into everyday life, since they’re basically schematic but universal models of human behavior.

For those in the know, it’s very easy to use concepts like NPC (non-player character), grinding or looting as metaphors. In my case, the notion of metagame helped me understand everything that surrounds an activity but is not the activity itself.

Let’s take a concrete example closely tied to what we do at 421. Writing is an activity you can do without asking for anyone’s permission: alone at home, or in a bar, with pen and paper or a computer. If your goal is to write well, that’s a different story. There’s the history of writing as a medium, language functions, analysis, and of course literature. That’s where a first difference appears: whether you write without expectations, or with some intention of inscribing yourself in a millennia-long tradition. Already there, you have a small – and not at all negligible – metagame.

Now suppose you navigate that first metagame of how to write, or how to write well enough, legibly enough, in line with the canon of the time or the symbolic validation criteria of your peers. And you want more: you don’t just want to write, you want to be read, you want to publish. That’s when another song begins. Another metagame.

You can publish on your own, in a digital outlet. You just open a page on whatever platform is currently “meta” – once Blogger, then WordPress, then Medium, now Substack. Maybe you explore X, Instagram, Facebook. And that’s where the audience problem begins. In a world saturated with content, you need to stand out somehow. Welcome to the metagame.

The next level of complexity is making money from what you write, which opens up a whole new layer of competition, validation systems, networks of contacts, and a long list of things that repeats across any activity where you try to do the same.

In short, life is about playing different games, and finding the solutions or design space of each metagame is the best way to improve your performance in each area. It’s a way of seeing the world through competition and of asking which skills you need to stand out in each setting.

Yes, this mindset can be deeply stressful in many cases, because it projects a competitive, performance-oriented lens onto something that’s already hard enough: doing well the thing you care about. Still, you’re free to ignore this approach and tune it out – but that won’t make the meta disappear, or stop those who do prepare for it from having an advantage.

It’s also true that some people simply shine, and that’s enough. But to be honest, the sample of those “naturals” is very small: people who just strike the ball differently. People who “naturally” stand out for being very good at what they do – whether through innate talent or training from a very young age.

And even then, if you dig into that supposed naturalness, you often find that they hold some kind of sui generis concept of the metagame. In other words: even if they’ve never heard the term, they operate very effectively in the metagame they happened (or chose) to play. Excess talent helps, of course.

For those of us who are workers – or trainees – in each field we touch, there’s no alternative but to grind: to work exhaustively and consistently on improving what we do and to level up in the metagame that comes with it.

A Metagame to Rule Them All

So we can think of every human activity – studying, working, doing politics, making art, participating in an academic or professional field – as a metagame, because no action exists in isolation. It’s embedded in an environment where you have to anticipate what others are doing, adjust your strategy, position yourself, and read trends.

Just like in Magic, “playing your hand well” is not enough: you need to know which decks dominate, what you’re expected to do, where the gaps in the ecosystem are, and which adjustments give you an edge.

In academia, for example, research isn’t simply “producing knowledge”. It’s navigating a metagame made of dominant agendas, criteria of legitimacy, journals, citation incentives, and disputes between approaches. Studying a topic isn’t just reading and writing; it’s understanding how the field moves, where the theoretical gaps are, which moves position you to be read, funded, or accepted.

In the workplace it’s the same story. Working isn’t just doing tasks; it’s reading your industry’s metagame: which skills are on the rise, which technologies are becoming standard, which roles are going obsolete, what signals the people who get promoted are sending, and which career paths have the highest win rate.

Social networks are the metagame of attention. It’s not only what you post that matters, but how the algorithm moves, which formats it favors, how cultural codes mutate, which narratives dominate, and what content is optimized to cut through feed inertia.

Even art operates as a metagame. You don’t just “create” in a vacuum; you work inside a cultural system with scenes, institutions, forms of legitimacy, trends, shifting audiences, curators as gatekeepers, and historical moments that open or close doors. Each individual work gets played on the table, but your artistic career – its reception and impact – gets cooked in the meta, where each gesture responds to what’s already in circulation.

Conclusion

Seen this way, the concept of metagame gives us a tool to think about practical life as a strategic ecosystem where it’s not enough to “be good” at the task at hand if your goal is to become a professional in that field. You need to read the map, anticipate moves, position yourself, and understand that you operate within dynamic structures that reconfigure themselves based on what others do.

At the same time, there is no moral imperative to grind. Many people (perhaps most) are perfectly happy simply doing what they like, or something they like, without any greater ambition than that. In that sense, that’s a life choice much more in line with what we’ve been exploring here: you can absolutely decide not to grind.

You can even approach reading the metagame as an activity in itself. Not to participate or compete, but just because you enjoy observing. That’s a bit of what happens on X, where plenty of people freely comment on things they don’t actually practice, from politics to football. You don’t need to be an active player to have a reasonably solid grasp of a metagame.

The trade-off is that the spectator loses access to first-hand information about the state of the meta and depends on (more or less reliable) information sources, which can radically change how things look. The side of the counter you’re on is a decisive factor in the kind of information you can get.

In any case, choosing whether or not to grind is up to you – but once you become aware of them, the existence of metagames in every activity is something you can’t really unsee.