During the second half of the ’90s, Sony had a semi-official push to limit 2D releases on PlayStation —at least in the West. The console’s identity was polygonal 3D, so the company worked hard to distance the brand from sprite-based games. A few titles from Japanese heavyweights like Konami (Castlevania: Symphony of the Night) or Capcom (Mega Man X4) still made it through. Others —like early entries in the Atelier JRPG series or the run-and-gun Gunners Heaven— weren’t as fortunate.

And yet, despite that attempt to sideline some of the most iconic pixel-styled games, the aesthetic is still alive and thriving. Titles like Terraria and Stardew Valley are perennial fixtures near the top of Steam charts. Every year, a new pixel-art indie breakout takes the world by storm —Balatro being a recent example. And Minecraft, despite being 3D, draws heavily from that look —and remains the best-selling game of all time.

Why does a visual style that once looked hopelessly out of fashion now feel more relevant than ever —so much so that one of Argentina’s most active studios, LCB Game Studio, has built its identity around it? Let’s start with the basics.

What Is Pixel Art?

Before we ask why pixel art remains popular, we should define what we mean. Not all video game graphics, retro games, or 2D illustrations qualify as pixel art. I’ll borrow a definition from Daniel Silber, author of Pixel Art for Game Developers (2016): an image where every visible on-screen pixel is placed intentionally. You don’t have to plot them one by one —we’re not in 1980— but the intent has to be there.

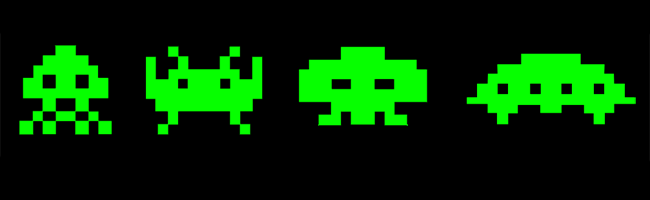

Pixel art’s reign has three major phases. The first begins in 1978 with Space Invaders. The game that kicked off the arcade boom may have been the first to produce truly iconic character designs. Vector graphics coexisted at the time (notably Asteroids or Battlezone), but most coin-op classics owe their appeal to pixels: without them, there’s no Pac-Man or Donkey Kong. At home, early consoles were heavily constrained, but after the Famicom launched in 1983 there was no escaping it —pixels took over every screen.

By the late ’80s, a second phase emerged. Better hardware let arcades —and then home consoles and PCs— showcase small wonders of digital art. The shift to 16-bit processors and larger memory budgets enabled more sophisticated techniques: color gradients, dithering, and effective anti-aliasing patterns. Consoles like the SNES could pull off advanced rotation and scaling effects in games like Super Castlevania IV, while on PC you could see early “proto-3D” in classics like Doom.

But every golden age ends. By the mid-’90s, gaming was pivoting hard toward 3D. With fewer 2D-heavy releases on consoles and PCs, pixel art found its refuge in handhelds: from roughly 1995 to 2005, the Game Boy family became the natural home for two-dimensional art. And at resolutions that didn’t even match the NES, pixel art wasn’t a choice —it was a necessity.

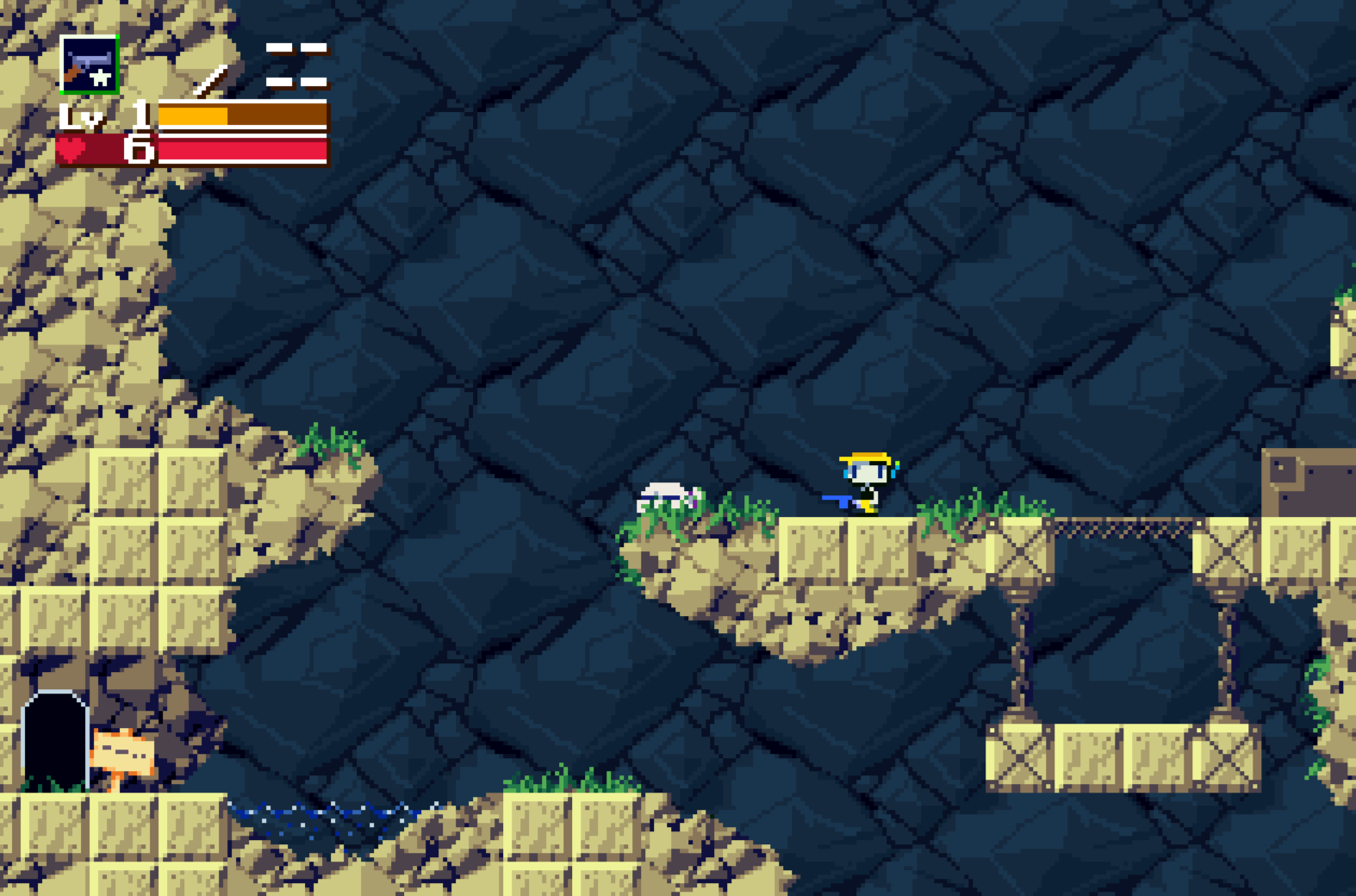

But as one door closed, another opened. In the mid-2000s, indie games began embracing the style —even on platforms with far higher resolutions than the hardware that originally required it. Titles like Cave Story (2004), La-Mulana (2006), the original Spelunky (2008), or Fez (2011) helped cement pixel art as a pillar of “indie” aesthetics, even though other foundational hits —Braid, World of Goo, Super Meat Boy, Limbo, or Cuphead— look nothing like it.

Nostalgia

The usual argument for this style’s staying power is nostalgia: millennial developers who grew up on 8- and 16-bit consoles trying to recapture the magic of their childhood games, with players responding to the same impulse.

I’m not fully sold on that explanation. Yes, some early indie breakouts used pixel art. But when the first of those games arrived, pixel art was still very much present on handhelds. Cave Story predates the end of the Game Boy line, for instance, and released just a year after Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow.

To be fair, many of these games (including Cave Story) are deliberately retro in certain ways. But others, like Spelunky, feel unmistakably modern. This isn’t simply nostalgia reenacting the past.

Simplicity

People often say indies love pixel art because it’s simpler than modern graphics. That’s a mistake.

Yes, a 2D game can be far simpler than a complex 3D production. But among 2D styles, pixel art isn’t the easiest. In fact, many indie hits that grew out of Flash-era web development —Super Meat Boy, for example— aren’t pixelated at all; they use cleaner, line-based art.

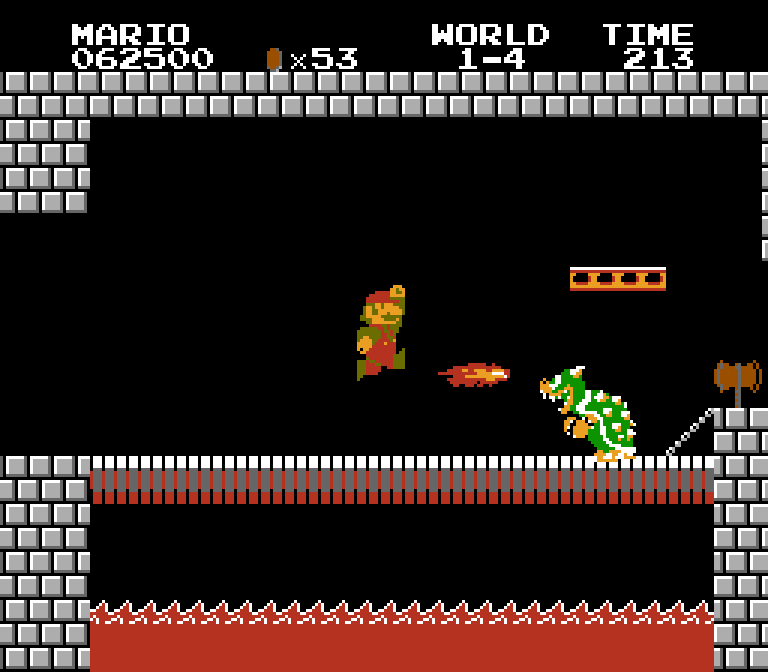

The confusion comes from older consoles: at low resolutions, almost any 2D art ends up looking “pixelly” by definition. Mario’s original small sprite in Super Mario Bros. is only 12×14 pixels. On an HD display, the real challenge is making the pixels readable and intentional.

Maybe some early pixel-art indies were simple —VVVVVV (2010) is a good example. But have you seen Blasphemous?

Or Owlboy?

Spend a few minutes with Dead Cells and tell me this aesthetic is “easy”.

No one in their right mind would call the artistry behind those games the path of least resistance.

So What Is It, Then?

So if it’s not just nostalgia —and it’s certainly not “easy”— what is it? Back to history: pixel art wasn’t the first visual language associated with video games (that honor goes to vector graphics), but it arrived early. And once games moved into the home, pixel art became inseparable from the medium. You can see it in the period packaging: early NES boxes proudly showcased chunky pixels —often not as screenshots, but as original illustrations that emphasized the look.

Beyond a few niche corners of early computer graphics, most people rarely encountered pixel art outside video games —or adjacent scenes like the demoscene.

That, I think, is the main appeal: pixel art is a visual language native to games —one that rarely migrated far beyond them. The closest parallel might be black-and-white in photography and cinema. For decades, monochrome had no real competitor. Color eventually took over, but black-and-white kept its devotees —sometimes for budget reasons (early self-financed debuts), sometimes for practicality (it’s easier to develop and more forgiving). Today it often signals tradition and intent —not necessarily nostalgia, but a dialogue with the past rather than an uncritical reenactment.

In the same way, a pixel-art game proudly declares what it is. It’s not trying to look like film, animation, or any other visual medium: first and foremost, it’s a game. And calling attention to the medium isn’t new. In a way, it echoes certain techniques from Impressionism —swapping the visible brushstroke for the hard-edged pixel.

Another effect is legibility. Unlike games chasing realism, a well-executed lo-fi style like pixel art is instantly readable: hazards, pickups, interactable objects, terrain, and background elements are easy to parse at a glance. You don’t need modern crutches like “detective vision” or the infamous yellow paint.

And that ties into my third and final point: deliberate unreality. A game that embraces its own playfulness doesn’t have to justify everything. Why does Bowser have open lava pits in his castles? Because it’s a game. Why can you only buy Poké Balls and visit the Pokémon Center in Viridian City —and not, say, a grocery store? Because it’s a game. Does touching a floating medkit instantly heal you? Of course —because it’s a damn game.

That’s why I think pixel art has a long future ahead —one it wouldn’t have if it were merely a millennial nostalgia artifact. You can run the most advanced ray tracing on a GPU with more cores than you care to count, but at the end of the day, games are games —and pixels will be with us for as long as we keep playing.

EN

EN