At this point, introducing The Matrix feels like stating the obvious –an obviousness the size of a house. But here we go. It also gives me an excuse to revisit that moment. It was 1999, and the Wachowskis –credited then as the Wachowski brothers, later transitioning, and now widely known as the Wachowski sisters– released one of the most influential films of its era. The Matrix follows Thomas Anderson, a programmer stuck in a megacorporate routine who suspects reality isn't all there is –that there's "something more". A chain of strange coincidences –his computer typing "follow the white rabbit" on its own, then a girl showing up with a white-rabbit tattoo– leads him to Morpheus, a political-religious leader (I mean, basically a guerrillero) who proposes the unthinkable: the world might be a fiction.

Some scattered attempts at resistance, here and there, until Mr. Anderson finally decides to cross the threshold. Morpheus offers him two pills: a blue one that wipes his memory and lets him keep living as he was, and a red one that takes him "to the desert of the real". Anderson –whose handle is Neo, and who from this point on will treat his digital identity as his real one– takes the red pill and wakes up inside a human incubator hooked up to a life-support system. A flying robot detects movement, flags him as defective, pulls him from the pod, and dumps him like trash. It's still unclear why the machines don't simply annihilate humans who "wake up" and save themselves the trouble. Or how they can't match "users inside the Matrix" to the bodies wired into pods, one by one. But anyway.

Down in the sewers of human waste, a hovercraft commanded by Morpheus rescues Neo and introduces him –finally– to the rest of the guerrilla cell. Welcome to the real Earth. Humanity has been crushed in a war against machines, and what remains of us serves as batteries for the robots. Yes: biological batteries, because during the war we "scorched the sky" (and it's presented as if nuclear power didn't exist). To prevent rebellion, the machines keep humans plugged into software that simulates the world that no longer exists. They keep us "alive" while siphoning our bodily energy. Only one human city holds out: Zion. From there, the resistance is organized, and the goal is to wake as many humans as possible and recruit them into this uneven fight. There's also a prophecy: a "Chosen One" may arrive to end the war. Morpheus suspects it's Neo.

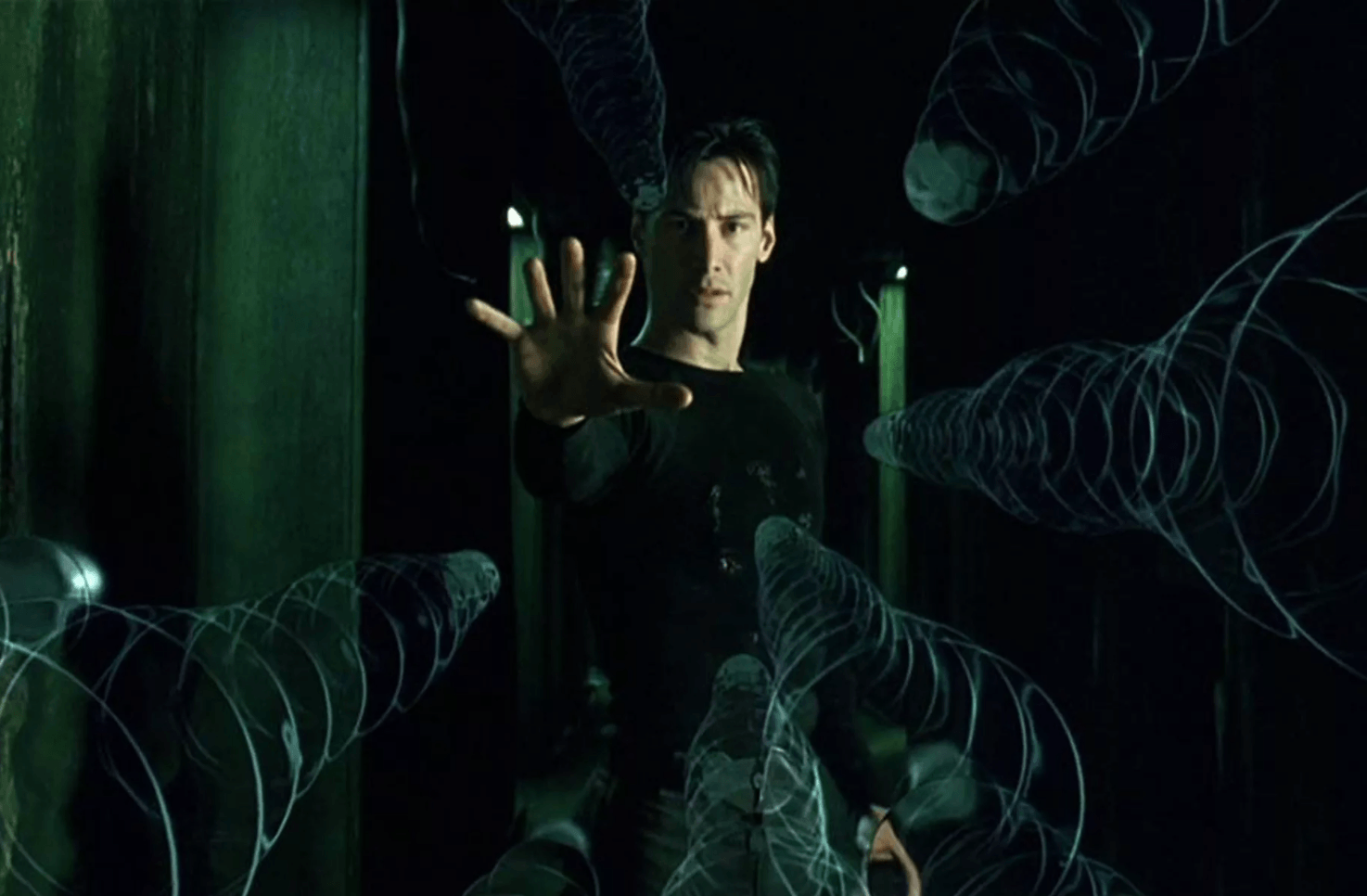

Beyond the simulation premise, The Matrix was also a triumph of visual effects. The now-canonical idea of bullet time –a character suspended mid-motion as the camera swings around in a 360– helped define the Y2K aesthetic, alongside a hard-techno soundtrack and a stylized appropriation of martial-arts cinema (including a few not-so-subtle lifts from Ghost in the Shell). Philosophy, "Eastern" aesthetics, and technology. Yes: like Blade Runner (1982), just more explicit, and twenty years later.

The impact was immediate. The film became a trilogy, multiple videogames followed, bullet time turned into a signature of the era, and concepts like the red pill / blue pill dichotomy ended up shaping online political discourse for decades. Simulation theory –and the scientific-philosophical debates orbiting it– became everyday talk. "Living inside the Matrix" turned into a common expression.

But the enthusiasm generated by the first film bled out with the sequels. To this day, popular consensus holds that The Matrix Reloaded (2003) and The Matrix Revolutions (2003) are uneven follow-ups that never match the original –especially thanks to the anticlimactic notion of "peace" between machines and humans. All that political-philosophical quilombo just to sign a truce? So the solution was class conciliation? What am I supposed to do with my Rage Against the Machine CDs?

Whether the sequels deserve some kind of rehabilitation –like the way some of us enjoy doing it with Episode I (1999) and St. Anger (2003)– is debatable. But the truth is: whatever the first Matrix hinted at never really got satisfied again. Or did it?

The Animatrix

The Animatrix came out in 2003, ahead of The Matrix Reloaded, and works as a bridge between the first and second films. In the early 2000s, ideas like multiverses, reboots, spin-offs, and retcons weren't yet mainstream in the way the MCU would normalize a decade later. Back then, what we mostly had were trilogies –still seen as the "proper" way to build a story, or rather, a franchise.

It started with Star Wars (1977), solidified in the '80s with Indiana Jones and Back to the Future, and even The Godfather (1972) became a trilogy. And then, in the 2000s, big trilogies came roaring back: the Star Wars prequels –try explaining, back then, that movies released AFTER the originals happened chronologically BEFORE them– plus X-Men (2000), Spider-Man (2002), and The Lord of the Rings (2001). The Matrix wasn't left out.

And between Episode II (2002) and Episode III (2004), we got Star Wars: Clone Wars (2003), an animated micro-series by Genndy Tartakovsky (Dexter's Laboratory, Samurai Jack, Primal), which served as connective tissue between the films and remains exquisite in both art direction and animation. I recommend it. As for The Animatrix, its roster is absurdly strong: Kōji Morimoto, Shinichirō Watanabe, Mahiro Maeda, Peter Chung, Andy Jones, Yoshiaki Kawajiri, and Takeshi Koike –names with credits spanning work like Ninja Scroll, Æon Flux, Cowboy Bebop, and plenty more. Titans, basically.

If you set aside the first short, "The Final Flight of the Osiris", which is the weakest, everything else expands the world introduced in the first film. That world needed more room to breathe –and more answers. Why do smugglers need a hardline phone to "exit" the Matrix? The Animatrix provides the kind of expansion that makes the setting feel complete, something the sequels strangely fail to do, even when they introduce autonomous programs like the Merovingian, the Oracle, the Trainman, the Twins, and so on.

Remember: the first film ends with Neo having defeated death and ready to lead the rebellion. That sense of momentum erodes in the follow-ups, where moral manicheism plus a strangely underbuilt world collapse under the expectations the first film created. The sequels couldn't clear the bar set by The Matrix. In that sense, what The Animatrix does –world-building through side angles– is far more significant. Let's look.

The Second Renaissance (Parts I and II)

The two shorts that make up "The Second Renaissance" tell the story of the war between humans and machines. Quick summary: the robot B1-66ER kills its human owner after the owner tries to destroy it. The robot is put on trial and found guilty. Humans launch a hunt against robots; the machines go into exile and found their own nation in the desert. Within a few years, Zero-One becomes the world's leading power –its currency the most widely used, its products everywhere. A triple narcissistic wound hits humanity, who feels threatened and declares war. Years of war. The machines perfect their techniques for hunting humans. Humans nuke them; it doesn't solve anything. Humanity decides to block out the sky beneath an immense cloud of unknown material. The machines respond by turning humans into batteries. They build the Matrix. End of story.

This frames The Matrix as a kind of Landian fable, where robots (i.e., technology) and the power of capital are one and the same –as if we still needed that spelled out. Among the many philosophical readings of The Matrix (Descartes' Evil Genius, Plato's Cave, Hilary Putnam's "Brains in a Vat"), the one that interests me most treats the Matrix as a substitute for "ideology" in Marx (the veil that hides reality), and the Matrix as the capitalist mode of production itself (literally: machines extracting human value). The skeptical "what is reality?" readings are fine, but they fall short. Yes, the saga plays with mind-body dualism, and often implies a primacy of the mental over the physical –but when all is said and done, material reality and the very real risk of mutual extermination between humans and machines are what prevail.

There's also a new spin on Frankenstein. Humans can't tolerate that their "children" (A) rebel, and (B) outperform them at capitalism. Once again, a botched parent-child relationship –or, more precisely, an unresolved "surpassing"– turns into extinction. And this is far from an anti-machine fable, oddly enough. In a Hegelian thesis-antithesis-synthesis structure, the Matrix becomes the "solution" to a symbiotic, conflictual relationship between human and machine: a grim equilibrium built on mutual intentions of annihilation. "The Second Renaissance" is, by far, one of the best films about this anticipated war and mutual extermination that fiction has teased from Frankenstein to Terminator. It's also what the Terminator saga always left hanging after the first two films: the machine war, the rise of John Connor, and the time travel that kicks off the loop.

A Kid's Story – A Detective Story – World Record

These three share a theme: how people inside the Matrix might come to sense the virtual, illusory nature of their world. In "A Kid's Story", a teenager communicates with Neo through his computer. In full adolescent intensity, he becomes convinced there's more to reality. Agents arrive at his school, chase him, and once cornered he makes a drastic choice: he throws himself into the void. His suicide inside the Matrix is what makes him exit it. Controversial.

In "A Detective Story", film noir becomes the excuse to throw a private investigator into Trinity's orbit –and to flirt with the possibility of escaping the Matrix. The idea is maybe slightly thin, but the execution is brilliant.

"World Record" is my favorite of the three. The animation is legendary, but the best part is the concept. A 100-meter sprinter runs so fast his muscles rupture –yet instead of stopping, he keeps going, past physical impossibility. By pushing beyond his limit, he defeats his body with his mind. That moment wakes him from the Matrix and puts him within reach of the agents, who immediately notice what's happening. He ends up prostrate and lobotomized, waiting in a wheelchair. But for an instant, he stands again –feeling, at least once more, the freedom he tasted during the incident. I love this one for two reasons. First, it suggests there are "spontaneous" exits from the Matrix: individuals who break the veil on their own, without guides or drugs, simply by driving existence to the edge. Second, it feeds into something the saga keeps implying: the primacy of the mental over the physical.

Across the films –especially the first– the mind is framed as the true command center. You see it in the training sequences between Neo and Morpheus, where Neo has to unlearn every convention he associates with "reality", from physics to death itself. The primacy of the mental becomes clearest here, because until Neo arrives, dying in the Matrix means the real body dies too. If the mind concludes "you're dead", then you're dead.

It's clearest in the dialogue with the child during Neo's first visit to the Oracle, when Neo asks how he bent the spoon and the kid says: "There is no spoon". In a now-deleted tweet, I once said that for me this idea is even stronger than the red-pill/blue-pill dichotomy. This is where the film's radical skepticism really sits. If Descartes is right and we live under the influence of an Evil Genius –an immediately superior power that can deceive us about reality, make the false seem true, and even warp the truths of logic or mathematics– then why believe any of this is real? And if you suspect the world is a hoax, or a fiction, then you might as well act accordingly and do whatever you want. I can't help thinking some of this hovers behind the Wachowski sisters' decision to transition. It's not only a primacy of mind –it's a primacy of belief. To what extent does what I believe give me more agency in the world? More… freedom?

It's no accident that the metaphor for "mental reality" is software –and that the rebels are "hackers". The concept of hacking reality floats over the entire work.

Beyond

"Beyond" is the short that fascinated me the most, alongside "World Record". A group of kids finds a "haunted house" that turns out to be nothing less than a massive glitch in the Matrix. As they play inside it and watch the laws of physics break repeatedly, a containment team heads out to erase the anomaly. In the end, they seal it and wipe it clean without leaving a trace.

Two things obsess me here. First, the short makes "glitch" tangible, which lets the "fantastic" exist inside the Matrix while still being explained as system failure. Second, its protagonists are ordinary people with no connection to Neo, Trinity, or Morpheus. They never fully question the world's existence –yet they can't explain what's happening. They sense something is off, but it's not enough. And their approach to the "haunted" place is intensely playful. This is what The Matrix could have used more of: less cliché machine-war escalation, more eerie systemic leakage.

Also, remember how by the end the Matrix becomes a kind of ghost zone where everyone is basically Agent Smith's copy, and they fight Neo to the death? What happens there to the primacy of the mental? Don't those humans die when Smith wipes their psychic structure? The Matrix shifts from being a total necessity to something almost accessory.

Matriculated – Program

In these last two, one short explores rewriting a machine's "software" so it can become –at least potentially– benevolent toward humans ("Matriculated"). The other ("Program") frames a training simulation as a moral test, where attachment, loyalty, and the line between "real" and "simulated" get weaponized. "Program" is impeccable in animation and tightly told, though it doesn't expand the mythos as much as "Matriculated" does. "Matriculated", meanwhile, opens the door to a symbiotic human-machine relationship that could, in theory, heal the great narcissistic wound and offer some kind of redemption to Frankenstein –something you can feel echoed later in The Matrix Resurrections (2021).

And maybe this is the saga's weakest point overall. I was talking a few months ago with Fede Carrone, and he said the part that bothered him most was the "humans as batteries" premise. And he's right: it doesn't make sense. The machines would have a thousand more efficient ways to generate energy. But precisely in that weak point –one that hasn't aged well– sits the work's meaning. The Wachowskis tried to stage a mutual dependency between the two "natures", and that's also the most controversial part. If you think about it, the machines have every advantage. They could erase humans once and for all. But the narrative only works if the machines stand in for capital and extraction –if there's a counterpart to exploit.

In that sense, The Matrix feels like a direct heir to Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927), with its famous formula: the mediator between the Head (the elite that governs and builds the machine) and the Hands (the working masses) must be the Heart. Which places it in the long tradition of science-fiction films that land, finally, on class conciliation (Is this Peronism?). It's also a little disappointing as a resolution, because you expect something more drastic, given the conflict's inherent nature in The Matrix –and in the capital-labor relationship it can't stop invoking.